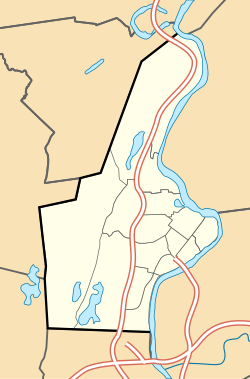

South Holyoke is a neighborhood in Holyoke, Massachusetts, located approximately 0.5 miles (0.80 km) south of the city center. Today the neighborhood contains many historical brick tenements and 165 acres (67 ha) of mixed residential, commercial, and industrial zoning including many of the remaining businesses of the city's paper industry. The neighborhood is also home to the city's Puerto Rican-Afro Caribbean Cultural Center, the Carlos Vega and Valley Arena Parks, as well as the Holyoke Turner Hall, one of the last remaining turnvereines in New England, and the William G. Morgan Elementary School.[3][4] In 2018, South Holyoke had the highest percentage of renter-occupied housing of any Massachusetts neighborhood outside of Boston, with an average of 1.5% owner-occupied households across the neighborhood's two census block groups.[5]

South Holyoke | |

|---|---|

Commercial blocks on Main Street | |

| Coordinates: 42°11′48.2892″N 72°36′27.972″W / 42.196747000°N 72.60777000°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| City | Holyoke |

| Wards | 1, 2 |

| Precincts | 1A, 2A, 2B |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.26 sq mi (0.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 72 ft (22 m) |

| ZIP code | 01040 |

| Area code | 413 |

| MACRIS ID | HLY.W |

History

editIn the mid-19th century the area was predominantly open land with some factories and brickyards,[6] and was originally known as Tigertown, as it hosted a number of baseball teams with one Boston Globe writer later attributing the name to the fact that "local baseball men played for blood and showed such tigerish propensities toward rival teams if the game did not go to their liking".[7] In the earliest days, the players and attendees of these games as well as the settlers of the area were largely Irish, as one of the three early working class Irish settlements in Holyoke, rarely referred to as "The Bush", with others being "The Patch" in the downtown and "The Flats" to the north.[8]

By the 1890s these baseball fields had largely disappeared and the area became characterized by factories and worker housing, seeing influxes of different immigrant groups from Germany; with industrialist millwrights emigrating from Rhineland and about half of workers from Saxony,[9] by 1875 it had the highest population, per capita, of German immigrants of any neighborhood or ward in New England, representing 88% of residents.[10][11] In subsequent decades this demographic would Americanize and dissipate, with other immigrant communities settling there from Canada, Greece, and Puerto Rico into the 20th century.[12] There was a large "post-Hurricane Maria migration of Puerto Ricans" to Holyoke after Hurricane Maria struck the island of Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017.[13] As of 2018, the neighborhood's residents were predominantly Puerto Rican, with the highest concentration of any such population in Holyoke or New England, representing 73.3% of residents.[14] On December 10, 2019, as part of a $72 statewide initiative, Governor Charlie Baker's administration announced a $6.56 million grant to support street, alley, and traffic infrastructure improvement in the neighborhood around Carlos Vega Park. The grant was part of a larger set of projects, including a mixed owner-renter housing development around the park to be funded and built by the Holyoke Housing Authority, and capital infrastructure improvement by the Water Works.[15]

Further reading

edit- "The People of Holyoke; Great Proportion of Them Foreigners; What is Being Done for Their Americanization—Forces of Law, Education and Example". New-York Tribune. New York. November 9, 1902. p. 14 – via Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

References

edit- ^ Spatial analysis of "Holyoke Neighborhoods" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 3 Jun 2016.

- ^ "Highlands, Holyoke, Massachusetts". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 3 Jun 2016.

- ^ Plaisance, Mike (June 4, 2018). "Hurricane season prompts Holyoke fundraisers to help Puerto Rican towns". The Republican. Springfield, Mass. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018.

- ^ Hofmann, Annette. "Translating Gymnastics Into Economic and Political Power: The Rise and Decline of the German Turnverein in Holyoke, Massachusetts, 1871–1910". Turnen and Sport. New York: Waxmann Münster. pp. 121–147.

- ^ "2018 Planning Database". Research@Census. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018: Block Groups 250138115001, 250138115002

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Wiesinger, Gerwart (1994). Die deutsche Einwandererkolonie von Holyoke, Massachusetts, 1865–1920 [The German Immigrant Colony of Holyoke, Massachusetts, 1865–1920] (in German). Stuttgart: F. Steiner Verlag. p. 61. OCLC 31941276.

- ^ "Holyoke; Mayor Smith Indorsed [sic] in the Caucuses— Old Names of Suburban Villages". Boston Sunday Globe. Boston. November 14, 1897. p. 62.

South Holyoke of today bears little resemblance to the 'Tigertown' of former days. In the days gone by the local baseball men played for blood and showed such tigerish propensities toward rival teams if the game did not go to their liking that perhaps this may have earned the cognomen of 'Tigertown.' A well-known baseball man recalls the feverish excitement which was developed whenever Springfield and Holyoye [sic] met on a ball field. It was invariably a gory battle, so much so that when Springfield came up here to play the local team, a squad of police, larger than the two ball nines, was required to bring the game to a peaceful ending

- ^ Green, Constance McLaughlin (1957). American Cities in the Growth of the Nation. New York: J. De Graff. p. 88. OCLC 786169259.

- ^ "The German Component to American Industrialization (1840–1893)". Immigrant Entrepreneurship; German-American Business Biographies. German Historical Institute; German Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019.

- ^ Gerhard Wiesinger (2004). "Translating Gymnastics Into Economic and Political Power: The Rise and Decline of the German Turnverein in Holyoke, Massachusetts, 1871–1910". In Annette R. Hofmann (ed.). Turnen and Sport. New York, München, Berlin: Waxmann Münster. pp. 121–146.

- ^ McCaffery, Robert Paul (1996). Islands of Deutschtum: German-Americans in Manchester, New Hampshire and Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1870–1942. P. Lang. p. 72.

At one point the Germania [Mills] employed seventy-five percent of the Germans in Holyoke. The ward surrounding the Germania became eight-eight percent German, the highest German concentration of any New England City

- ^ "MACRIS inventory record for The Flats – South Holyoke, Holyoke". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ Vargas Ramos, Carlos. "Anticipated Vulnerabilities: Displacement and Migration in the Age of Climate Change" (PDF). centropr.hunter.cuny.edu. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Ancestry in Holyoke, Massachusetts (City)". Statistical Atlas. Cedar Lake Ventures, Inc. Archived from the original on February 6, 2019.

South Holyoke [Ancestry map filtered to "Puerto Rican"]: 83.3%

- ^ Office of Governor Charlie Baker and Lt. Governor Karyn Polito (December 10, 2019). "Baker-Polito Administration Announces $6.56 Million MassWorks Infrastructure Award in Holyoke". MassWorks. Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development; Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019.