Sonnet 73, one of the most famous of William Shakespeare's 154 sonnets, focuses on the theme of old age. The sonnet addresses the Fair Youth. Each of the three quatrains contains a metaphor: Autumn, the passing of a day, and the dying out of a fire. Each metaphor proposes a way the young man may see the poet.[2]

| Sonnet 73 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

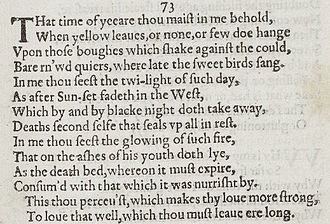

Sonnet 73 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Analysis and synopsis

editBarbara Estermann discusses William Shakespeare's Sonnet 73 in relation to the beginning of the Renaissance. She argues that the speaker of Sonnet 73 is comparing himself to the universe through his transition from "the physical act of aging to his final act of dying, and then to his death".[3] Esterman clarifies that throughout the three quatrains of Shakespeare's Sonnet 73; the speaker "demonstrates man's relationship to the cosmos and the parallel properties which ultimately reveal his humanity and his link to the universe. Shakespeare thus compares the fading of his youth through the three elements of the universe: the fading of life, the fading of the light, and the dying of the fire".[3]

The first quatrain is described by Seymour-Smith: "a highly compressed metaphor in which Shakespeare visualizes the ruined arches of churches, the memory of singing voices still echoing in them, and compares this with the naked boughs of early winter with which he identifies himself".[4]

In the second quatrain, Shakespeare focuses on the "twilight of such day" as death approaches throughout the nighttime. Barbara Estermann states that "he is concerned with the change of light, from twilight to sunset to black night, revealing the last hours of life".[3]

Of the third quatrain, Carl D. Atkins remarks, "As the fire goes out when the wood which has been feeding it is consumed, so is life extinguished when the strength of youth is past".[5] Barbara Estermann says it is concerned with "the fading out of life's energy".[3]

Structure

editSonnet 73 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the rhyme scheme of the English sonnet form, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. It is composed in iambic pentameter, a poetic metre that has five feet per line, and each foot has two syllables accented weak then strong. Almost all of the lines follow this without variation, including the second line:

× / × / × / × / × / When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang (73.2)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Structure and metaphors

editThe organization of the poem serves many roles in the overall effectiveness of the poem. Yet, one of the major roles implied by this scheme revolves around ending each quatrain with a complete phrase. Given the rhyme scheme of every other line within the quatrain, as an audience we are to infer a statement is being made by the end of every four lines. Further, when shifted toward the next four lines, a shift in the overall thought process is being made by the author.

If Shakespeare's use of a complete phrase within the rhyme scheme implies a statement then the use of a consistent metaphor at the end of each quatrain shows both the author's acknowledgement of his own mortality and a cynical view on aging. This view on aging is interconnected with the inverse introduction of each symbol within the poem. By dropping from a year, to a day, to the brief duration of a fire, Shakespeare is establishing empathy for our speaker through the lapse in time.[6] Additionally, the three metaphors utilized pointed to the universal natural phenomenon linked with existence. This phenomenon involved the realization of transience, decay, and death.[7]

Overall, the structure and use of metaphors are two connected entities toward the overall progression within the sonnet. Seen as a harsh critic on age, Shakespeare sets up the negative effects of aging in the three quatrains of this poem. These aspects not only take on a universal aspect from the symbols, but represent the inevitability of a gradual lapse in the element of time in general from their placement in the poem. Further, many of the metaphors utilized in this sonnet were personified and overwhelmed by this connection between the speaker's youth and death bed.[8]

Interpretation and criticism

editJohn Prince says that the speaker is telling his listener about his own life and the certainty of death in his near future. The reader perceives this imminent death and, because he does, he loves the author even more. However, an alternative understanding of the sonnet presented by Prince asserts that the author does not intend to address death, but rather the passage of youth. With this, the topic of the sonnet moves from the speaker's life to the listener's life.[9]

Regarding the last line, "this thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, to love that well which thou must leave ere long", Prince asks:

Why, if the speaker is referring to his own life, does he state that the listener must "leave" the speaker's life? If the "that" in the final line does refer to the speaker's life, then why doesn't the last line read "To love that well which thou must lose ere long?" Or why doesn't the action of leaving have as its subject the "I", the poet, who in death would leave behind his auditor?[9]

Bernhard Frank criticizes the metaphors Shakespeare uses to describe the passage of time, be it the coming of death or simply the loss of youth. Though lyrical, they are logically off and quite cliché, being the overused themes of seasonal change, sunset, and burn. In fact, the only notably original line is the one concerning leaves, stating that "when yellow leaves, or none, or few do hang, upon those boughs".[6] Logic would require that few should precede none; in fact, if the boughs were bare, no leaves would hang. Frank argues that Shakespeare did this on purpose, evoking sympathy from the reader as they "wish to nurse and cherish what little is left", taking him through the logic of pathos – ruefulness, to resignation, to sympathy.[10] This logic, Frank asserts, dictates the entire sonnet. Instead of moving from hour, to day, to year with fire, then sunset, then seasons, Shakespeare moves backwards. By making time shorter and shorter, the reader's fleeting mortality comes into focus, while sympathy for the speaker grows. This logic of pathos can be seen in the images in the sonnet's three quatrains. Frank explains:

Think now of the sonnet's three quatrains as a rectangular grid with one row for each of the governing images, and with four vertical columns:

spring summer fall winter morning noon evening night tree log ember ashes These divisions of the images seem perfectly congruous, but they are not. In the year the cold of winter takes up one quarter of the row; in the day, night takes up one half of the row; in the final row, however, death begins the moment the tree is chopped down into logs.[10]

This is a gradual progression to hopelessness. The sun goes away in the winter, but returns in the spring; it sets in the evening, but will rise in the morning; but the tree that has been chopped into logs and burned into ashes will never grow again. Frank concludes by arguing that the end couplet, compared to the beautifully crafted logic of pathos created prior, is anticlimactic and redundant. The poem's first three quatrains mean more to the reader than the seemingly important summation of the final couplet.[10]

Though he agrees with Frank in that the poem seems to create two themes, one which argues for devotion from a younger lover to one who will not be around much longer, and another which urges the young lover to enjoy his fleeting youth, James Schiffer asserts that the final couplet, instead of being unneeded and unimportant, brings the two interpretations together. In order to understand this, he explains that the reader must look at the preceding sonnets, 71 and 72, and the subsequent sonnet, 74. He explains:

The older poet may desire to "love more strong" from the younger man but feels, as 72 discloses, that he does not deserve it. This psychological conflict explains why the couplet hovers equivocally between the conclusions "to love me", which the persona cannot bring himself to ask for outright, and "to love your youth", the impersonal alternative exacted by his self-contempt.[11]

By reading the final couplet in this manner, the reader will realize that the two discordant meanings of the final statement do in fact merge to provide a more complex impression of the author's state of mind. Furthermore, this successfully puts the focus of the reader on the psyche of the "I", which is the subject of the following sonnet 74.

Possible sources for the third quatrain's metaphor

editA few possible sources have been suggested for both of two passages in Shakespeare's works: a scene in the play Pericles, and the third quatrain in Sonnet 73. In the scene in Pericles an emblem or impresa borne on a shield is described as bearing the image of a burning torch held upside down along with the Latin phrase Qui me alit, me extinguit ("what nourishes me, destroys me").[12] In the quatrain of Sonnet 73 the image is of a fire being choked by ashes, which is a bit different from an upside down torch, however the quatrain contains in English the same idea that is expressed in Latin on the impressa in Pericles: "Consum'd with that which it was nourished by." "Consumed" may not be the obvious word choice for being extinguished by ashes, but it allows for the irony of a consuming fire being consumed.[13][14]

One suggestion that has often been made is that Shakespeare's source may be Geoffrey Whitney's 1586 book, A Choice of Emblemes, in which there is an impresa or emblem, on which is the motto Qui me alit me extinguit, along with the image of a down-turned torch. This is followed by an explanation:

- Even as the waxe doth feede and quenche the flame,

- So, loue giues life; and love, dispaire doth giue:

- The godlie loue, doth louers croune with fame:

- The wicked loue, in shame dothe make them liue.

- Then leaue to loue, or loue as reason will,

- For, louers lewde doe vainlie langishe still.[15][16][17]

Joseph Kau suggests an alternate possible source – Samuel Daniel. In 1585 Daniel published the first English treatise and commentary on emblems, The Worthy Tract of Paulus Jovius,[18] which was a translation of Paolo Giovio's Dialogo Dell’ Imprese Militairi et Amorose (Rome 1555). Appended to this work is "A discourse of Impreses", the first English collection of emblems, in which Daniel describes an impresa that contains the image of a down-turned torch:

- "An amorous gentleman of Milan bare in his Standard a Torch figured burning, and turning downeward, whereby the melting wax falling in great aboundance, quencheth the flame. With this Posie thereunto. Quod me alit me extinguit. Alluding to a Lady whose beautie did foster his love, and whose disdayne did endamage his life."[19]

Kau's suggestion, however, has been confuted, because Kau made it crucial to his argument that Shakespeare and Daniel both used the Latin word quod rather than qui, however Shakespeare in fact nowhere uses the word quod.[20]

According to Alan R. Young, the likeliest source is Claude Paradin's post 1561 book Devises Heroïques, primarily because of the exactness and the detail with which it supports the scene in Pericles.[21]

Recordings

edit- Paul Kelly, for the 2016 album, Seven Sonnets & a Song

References

edit- ^ Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 257 ISBN 9781408017975.

- ^ Hovey 1962.

- ^ a b c d Estermann 1980.

- ^ Atkins 2007, p. 197.

- ^ Atkins 2007, p. 198.

- ^ a b Frank 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Schroeter 1962.

- ^ Booth 2000, p. 260.

- ^ a b Prince 1997, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Frank 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Pequigney 2013, p. 294.

- ^ Shakespeare, William. Pericles. Act II, scene 2, line 32 - 33.

- ^ Young, Alan R. "A Note on the Tournament Impresa in Pericles". Shakespeare Quarterly Vol 36 Number 4(1985) pp. 453-456

- ^ Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0300019599. p. 579

- ^ Whitney, Geoffrey. Green, Henry, editor. A Choice of Emblemes. Georg Olms Verlag, 1971. Reprinted facsimile edition. ISBN 9783487402116

- ^ Schaar, Claes. Qui me alit me extinguit. English Studies., No. 49. Copenhagen (1960)

- ^ Green, Henry. Shakespeare and the Emblem Writers. London (1870). Forgotten Books (reprinted 2018). pp. 171-74. ISBN 978-0260465986

- ^ Daniel, Samuel. The Worthy Tract of Paulus Jovius. Publisher: London, Simon Waterson. 1585.

- ^ Kau 1975.

- ^ Young, Alan R. "A Note on the Tournament Impresa in Pericles". Shakespeare Quarterly Vol 36 Number 4(1985) pp. 453-456

- ^ Young, Alan R. "A Note on the Tournament Impresa in Pericles". Shakespeare Quarterly Vol 36 Number 4(1985). pp. 453-456

Bibliography

edit- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Estermann, Barbara (1980). "Shakespeare's Sonnet 73". The Explicator. 38 (3). Routledge: 11. doi:10.1080/00144940.1980.11483372. ISSN 0014-4940 – via Taylor & Francis.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [first published 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Analytic Commentary (revised ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 9780300085068. OCLC 2968040.

- Frank, Bernhard (2003). "Shakespeare's Sonnet 73". The Explicator. 62 (1). Routledge: 3–4. doi:10.1080/00144940309597834. ISSN 0014-4940. S2CID 162267714 – via Taylor & Francis.

- Hovey, Richard B. (1962). "Sonnet 73". College English. 23 (8). National Council of Teachers of English: 672–673. doi:10.2307/373787. eISSN 2161-8178. ISSN 0010-0994. JSTOR 373787.

- Kau, Joseph (1975). "Daniel's Influence on an Image in Pericles and Sonnet 73: An Impresa of Destruction". Shakespeare Quarterly. 26 (1). Folger Shakespeare Library: 51–53. doi:10.2307/2869269. eISSN 1538-3555. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 2869269.

- Pequigney, Joseph (2013). "Sonnets 71–74: Texts and Contexts". In Schiffer, James (ed.). Shakespeare's Sonnets: Critical Essays. Shakespeare Criticism. Routledge. pp. 285–304. ISBN 9781135023256.

- Pooler, C. Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, first series. London: Methuen & Co. hdl:2027/uc1.32106001898029. OCLC 4770201. OL 7214172M.

- Prince, John S. (1997). "Shakespeare's Sonnet 73". The Explicator. 55 (4). Routledge: 197–199. doi:10.1080/00144940.1997.11484177. ISSN 0014-4940 – via Taylor & Francis.

- Schroeter, James (1962). "Sonnet 73: Reply". College English. 23 (8). National Council of Teachers of English: 673. doi:10.2307/373788. eISSN 2161-8178. ISSN 0010-0994. JSTOR 373788.

Further reading

edit- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.