This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

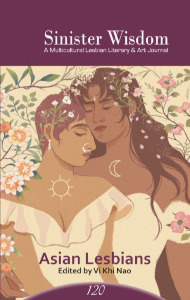

Sinister Wisdom is an American lesbian literary, theory, and art journal published quarterly in Berkeley, California. Started in 1976 by Catherine Nicholson and Harriet Ellenberger (Desmoines) in Charlotte, North Carolina, it is the longest established lesbian journal, with 128 issues as of 2023[update].[1] Each journal covers topics pertaining to the lesbian experience including creative writing, poetry, literary criticism and feminist theory. Sinister Wisdom accepts submissions from novice to accredited writers and has featured the works of writers and artists such as Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich. The journal has pioneered female publishing, working with female operated publishing companies such as Whole Women Press and Iowa City Women's Press.[citation needed] Sapphic Classics, a partnership between Sinister Wisdom and A Midsummer Night's Press, reprints classic lesbian works for contemporary audiences.[2]

| |

| Editor | Julie R. Enszer |

|---|---|

| Categories | Literary, art |

| Frequency | Quarterly |

| Publisher | Sinister Wisdom Inc. |

| First issue | 1976 |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | Dover, Florida |

| Website | sinisterwisdom |

| ISSN | 0196-1853 |

| OCLC | 3451636 |

History and mandate

editCatherine Nicholson and Harriet Ellenberger (Desmoines), two lesbians from Charlotte, North Carolina, attended a lesbian writing workshop in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1976 with the idea of a lesbian literary journal already in mind. Predecessors in the lesbian literary realm such as The Ladder and the Amazon Quarterly inspired Nicholson and Ellenberger (Desmoines) to create their own journal for Southern lesbians.[1] After attending the workshop, Nicholson and Ellenberger (Desmoines) submitted a leaflet calling for any lesbian writing to be part of a new journal. Ellenberger in particular called for "revolution, reversal, and transformation" and wanted a place that was outside of the patriarchal realm for lesbians to communicate and express themselves.[3] Sinister Wisdom was named after novelist and later Sinister Wisdom contributor Joanna Russ' novel The Female Man.[4] "Sinister" in this context means "on the left side", which is in direct contrast with the "right": the patriarchal, "rational" values that dominate society and seek to oppress the left. Ellenberger (Desmoines) writes in her first "Notes for a Magazine":[5]

The Law of the Fathers equates "right-over-left, white-over-black, heterosexual-over-homosexual, and male-over-female with good-over-evil." Sinister Wisdom turns these patriarchal values upside down as a necessary prelude to creating our own.

Ellenberger (Desmoines) believed that lesbians writing and publishing for lesbians outside of the traditional, patriarchal realm was the best way to connect to their audience. In addition to separatist content, the journal utilized the talents, time, and money of only women in a grassroots approach. This went against the publishing business that was mostly controlled by men.[1]

In July 1976, the first issue of Sinister Wisdom was released and was well received. Nicholson and Ellenberger (Desmoines) were the editors. The journal promised three issues a year with subscriptions costing $4.50.[5] The journal's first issue did not have a theme; the contents received for the issue were submitted on the basis of the original leaflet made by Nicholson and Ellenberger (Desmoines) and are thus diverse in subject and style. The second issue called for submissions pertaining to the overall theme of Lesbian Writing and Publishing and was released in the fall of 1976. The publication of the third issue in the spring of 1977 marked Sinister Wisdom's first year, and while Nicholson, Ellenberger (Desmoines), and their team still asked in every issue for more subscriptions and submissions, the journal could continue.

By Issue 7, Nicholson and Ellenberger (Desmoines) introduced some changes: the cost of subscriptions would be raised from $4.50 to $7.50 to cover costs, the number of issues released in the year would be raised from three to four, and Sinister Wisdom's publishing headquarters would move from Charlotte to Lincoln, Nebraska.[6] In Lincoln, the team at Sinister Wisdom worked with Iowa City Women's Press and Whole Women Press, two publishing businesses dedicated to publishing the work of women and lesbians and whom Ellenberger (Desmoines) thanks for helping keep the journal afloat. To continue to publish outside of the patriarchal system, the journal had to pay for their office space, supplies, printing, and mailing out of pocket.[7] Ellenberger (Desmoines) continued to urge readers to buy subscriptions for those who could not afford it, buy gift subscriptions, or donate extra money to Sinister Wisdom.[7]

Exhausted by the strains of editing and producing the journal, by 1978 Nicholson and Ellenberger began looking for women to replace them. At a party dedicated to female publishing in New York City, the two spoke with Adrienne Rich and Michelle Cliff.[1] Both Rich and Cliff were very well known in the world of lesbian literature and had been previous contributors to Sinister Wisdom. The pair decided to take on the project. Nicholson and Ellenberger (Desmoines)'s final issue was Issue 16 in the Winter of 1981, published outside of the journal's new headquarters in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Rich and Cliff promised to commit themselves to sustaining the quality of publications Sinister Wisdom was known for. As an activist and writer of color, Cliff noted in her first "Notes for a Magazine" that she was interested in including more submissions dealing with the intersections of race and lesbianism.[8] The journal from Issue 17 of the spring of 1981 was the start of a more intersectional journal, moving away from separatism and towards the inclusion of other forms of oppression that coincide with the experiences of lesbian women.

In the Summer of 1983, Rich and Cliff wrapped up their final issue at Sinister Wisdom and the journal was turned over to Michaele Uccella and Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz.[9]

By Issue 33, the magazine was turned over by Uccella and Kaye/Kantrowitz to notable feminist writer Elana Dykewomon. Dykewomon promised in this first issue as editor that she would work towards getting Sinister Wisdom to be recognized as a non-profit organization.[10] Dykewomon also became the publisher of the journal. By the spring of 1992, with the release of Issue 46, the journal received their 501(c)(3) from the government, recognizing the journal as a non-profit organization.[11] Sinister Wisdom began to be published by Sinister Wisdom Inc., as it continues to be today.

Issue 55, published as the spring and summer issue for 1995, was edited by Caryatis Cardea, Jamie Lee Evans, and Sauda Burch. The journal was then turned over to Akiba Onáda-Sikwoia. Onáda-Sikwoia states in her "Notes for a Magazine" that she wanted to boost the number of subscriptions but that her efforts had not yielded the projected 400 new subscriptions she was hoping for.[12] At this point, Sinister Wisdom provided 80 free subscriptions to incarcerated lesbians, an initiative that the journal has continued to the present.[12]

In 1997, Onáda-Sikwoia turned the journal over to Margo Mercedes-Rivera-Weiss, who would edit the journal until 2000. Fran Day, a feminist writer active in the lesbian community worked as the editor from 2000 until her death in 2010. Merry Gangemi was the editor from 2010 until 2013. The current editor is Julie R. Enszer.

In 2014, the journal received the Michele Karlsberg Leadership Award from the Publishing Triangle.[13][14]

Magazine and its content

editSinister Wisdom has 111 publications; four new, seasonal publications are released every year.[15] The journal features primarily lesbians' work, and is particularly interested in writing, art or photography that reflects diversity of experiences which includes, but is not limited to: lesbians of color, ethnic lesbians, Jewish, Arab, old, young, working-class, poverty class, disabled, and fat lesbians.[16]

Each issue of Sinister Wisdom is different in content and follows various structures. A section called "Notes for a Magazine" is written by the editor(s) of the issue, which explains the contents and theme of the journal, updates readers on any changes the journal will make, and calls for submissions. This letter from the editor(s) can be found usually at the beginning or at the end of the journal. Some issues dealing with specific topics are edited by guest editors.

The content and structure of the journals is dependent on the contributors submissions and if the journal is following a specific theme. Each journal features a "Call for Submissions" section that lets readers and contributors know what the upcoming issues will be focusing on.

The contributions to the journal often represent different mediums, such as art, photography, short stories, personal accounts, poems, interviews, feminist and queer theory, and literature reviews. The order of the contributions do not follow a specific pattern.

The back of the journal usually contains classified ads calling for specific submissions, workshops, conferences, publications, videos, and requests for correspondence. Ads also often advertise feminist bookstores where copies of Sinister Wisdom can be purchased, as well as other lesbian literature and arts journals for readers to subscribe to.

Identity and diversity

editSinister Wisdom is dedicated to representing the diverse nature of the lesbian community. Works featured in the journal include the experiences of lesbians from a variety of cultural, racial, religious, and class backgrounds. Several of the journal's issues have been dedicated to highlighting the experiences of specific affinity groups.

- Issues 29/30, "Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women's Anthology", were published in 1986.[17] This iteration of the journal highlights the experiences and creations of Jewish lesbians, including editor Elana Dykewomon.[18]

- Issue 39, "On Disability", was published in Winter 1989/1990.[17]

- Issue 41, "Il Viaggio Delle Donne: Italian-American Women Reach Shore", was published in Summer/Fall 1990.[17]

- Issue 45, "Lesbians & Class", was published in Winter 1991/1992.[17]

- Issue 53, "Old Lesbians/Dykes", was published in Summer/Fall 1994.[17] Works featured in the journal highlight the experiences of lesbians over the age of sixty, specifically dealing with topics such as sexuality, ageism, family, and death.[19] In Winter 2009/2010, issues 78 & 79 were published as a sequel to the 1994 issue in a collection entitled "Old Lesbians/Dykes II".[17]

- Issue 54, "Lesbians and Religion", addresses the experiences of lesbians from a number of religious and spiritual backgrounds.[17]

- Issue 97, "Out Latina Lesbians", was published in Summer 2015.[17] This issue, edited by Nívea Castro and Geny Cabral,[20] highlights the experiences of Latina lesbians and includes a number of pieces written in English, Spanish, or a mixture of both.

- Issue 107, "Black Lesbians—We Are the Revolution!", amplifies the voices of African-American lesbians and queer women.[17] This issue includes discussions of black and queer activism and the ways in which it is or isn't effective, and calls upon black lesbian/queer creatives to imagine a brighter future for activism.

Digital archives

editSinister Wisdom, in agreement with Reveal Media is in the process of digitizing back issues from 1976 to 2001.[21] In this agreement, Sinister Wisdom has made these back issues available on its website as downloadable PDFs to increase accessibility to lesbian literary content for readers.[22]

Editors and publishers

edit- Harriet Ellenberger (aka Desmoines) and Catherine Nicholson (1976–1981)

- Michelle Cliff and Adrienne Rich (1981–1983)

- Michaele Uccella (1983–1984)

- Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz (1983–1987)

- Elana Dykewomon (1987–1994)

- Caryatis Cardea (1991–1994)

- Akiba Onada-Sikwoia (1995–1997)

- Margo Mercedes Rivera-Weiss (1997–2000)

- Fran Day (2000–2011)

- Julie R. Enszer & Merry Gangemi (2010–2013)

- Julie R. Enszer (2013 to present)

Notable contributors

edit- Audre Lorde – notable poet, essayist, and activist

- Adrienne Rich – poet, writer, and activist

- Anita Cornwell – writer

- Susan Hawthorne – writer, poet, publisher

- Joanna Russ – novelist

- Elana Dykewomon – poet, novelist, editor, and activist

- Minnie Bruce Pratt – poet, activist, and teacher

- Deena Metzger – writer

- Michelle Cliff – writer and literary critic

- Pat Parker – poet

Other publications

editIn 2013, Sinister Wisdom began reprinting classic lesbian literature and poetry publications for a new audience to enjoy under Sapphic Classics. This initiative is in partnership with A Midsummer Night's Press, an independent publishing company specializing in poetry. Often these publications serve as an issue of Sinister Wisdom.

- Crime Against Nature by Minnie Bruce Pratt, Sinister Wisdom, Issue 88. This collection of stories and poems detailed Pratt's loss of custody of her two children when she came out as a lesbian. This book won Pratt the 1989 James Laughlin Award.

- Living as a Lesbian by Cheryl Clarke, Sinister Wisdom, Issue 91. This personal account details Clarke's life as a lesbian and pays tribute to women.

- What Can I Ask-New and Selected Poems 1975–2014 by Elana Dykewomon, Sinister Wisdom, Issue 96. This collection is the compiled poems and works of Elana Dykewomon.

- The Complete Works of Pat Parker, Sinister Wisdom, Issue 102. This collection is chosen works of Pat Parker. This collection won the Lambda Literary Award.

- For the Hard Ones: A Lesbian Phenomenology (Para las duras: Una fenomenología lesbiana) by Tatiana de la Tierre, Sinister Wisdom 108. This collection is a compilation of poetry exploring queer Latina sexuality in both Spanish and English.

Other publications:

- A Gathering of Spirit (Expanded)- This is an expanded version of the popular Issue 22/23, which showcases the work of Native American lesbians.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d Parks, Joy (Fall 2017). "Sinister Wisdom: A Chronicle". The Women's Review of Books. 1 (5): 14–15. doi:10.2307/4019378. JSTOR 4019378.

- ^ "History-By-Letter #1 | Iowa City Women's Press". 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2024-06-24.

- ^ Zimmerman, Bonnie (Fall 2017). "sinister wisdom's 15th anniversary!". Off Our Backs. 22: 17.

- ^ Endres, Kathleen L.; Lueck, Therese L., eds. (1996). Women's Periodicals in the United States. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. pp. 351–355. ISBN 978-0-313-28632-2.

- ^ a b Ellenberger, Harriet (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 1.

- ^ Ellenberger, Harriet (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 7.

- ^ a b Ellenberger, Harriet (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 8.

- ^ Cliff, Michelle (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 17.

- ^ Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 25.

- ^ Dykewomon, Elana (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 33.

- ^ Dykewomon, Elana (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 46.

- ^ a b Onáda-Sikwoia, Akiba (Fall 2017). "Notes for a Magazine". Sinister Wisdom. 56.

- ^ Enszer, Julie R. (2014-04-25). "Sinister Wisdom Receives Leadership Award From Publishing Triangle". HuffPost. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Publishing Triangle's 26th Annual Awards Presented April 24". Windy City Times. 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Journal". Sinister Wisdom. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Sinister Wisdom: What We Publish". Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Issues". Sinister Wisdom. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ Felman, Jyl Lynn (Spring 2011). "FORWARD AND BACKWARD: JEWISH LESBIAN WRITERS". Bridges: A Jewish Feminist Journal. 16. ProQuest 874328217.

- ^ Zimmerman, Bonnie (February 1992). "Sinister wisdom's 15th anniversary!". Off Our Backs. 22. ProQuest 233392258.

- ^ "Books and Media Received". Femspec. 17. 2016. ProQuest 1813982947.

- ^ "Digital Archive of Sinister Wisdom 1976-2000 | Sinister Wisdom". www.sinisterwisdom.org. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- ^ "Archive | Sinister Wisdom". sinisterwisdom.org. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

External links

edit- Official website of Sinister Wisdom