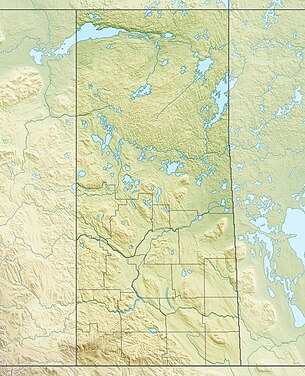

The siege of Battleford was a siege during the North-West Rebellion that lasted from 28 March to 26 May, 1885.

| Siege of Battleford | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North-West Rebellion | |||||||

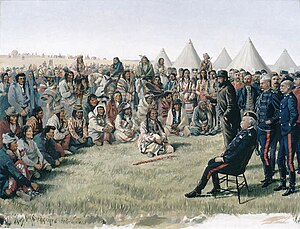

Poundmaker surrenders to Middleton in Battleford May 26, 1885 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cree |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Poundmaker |

William Morris[1] Frederick Middleton (late) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7 killed | 3 killed | ||||||

| 2-6 civilians killed | |||||||

Background

editAfter the Métis victory at the Battle of Duck Lake on March 26, 1885. Cree bands who were sympathetic to the Métis cause and with grievances of their own began raiding stores and farms in the western part of the District of Saskatchewan for arms, ammunition and food supplies. The raids caused civilians to flee to the larger settlements and forts of the North-West Territories.

Beginning of the siege

editOn 28 March 1885, news arrived that Indian bands commanded Poundmaker were on their way to Battleford. 500 civilians began moving into the nearby North-West Mounted Police post, Fort Battleford for protection against the Cree raids.[2] Fort Battleford was under the command of Colonel William Morris and had a small garrison of 25 police. During the night of March 29 nearby homesteads were raided their horses and cattle rounded up by the Cree. On March 30, Poundmaker asked for a meeting with the Indian agent J. M. Rae. After Rae refused to meet with him, the Cree raided food and supplies from abandoned stores and houses.[3] The next day, the Cree camped a few miles away bringing with them their looted provisions including cattle and horses then eventually returned to Poundmaker's reserve.[4] The New Town was protected due to its proximity to the Fort and its cannon. However, the Old Town was not. The occupants of the Fort could only watch as the Old Town, about a mile away, was plundered, looted and burned. Stolen vehicles and horses carried away the supplies of the Hudson's Bay Company and the other merchants. All the public buildings were sacked, including the Battleford Industrial School.[5] On 21 April 1885, Francis Dickens and his men safety reached Battleford after the Battle of Fort Pitt.[6][7]

Lifting the siege

editGeneral Middleton's original plan was simple. He planned to march all his troops north from the railhead at Qu’Appelle to the Riel's capital in Batoche as he predicted that capturing Batoche would end the rebellion.[8] Middleton was also under pressure from Canadian Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald to end the rebellion as quickly as possible.[8] Furthermore, the militiamen under his command were mostly untrained volunteers which Middleton had to train as they marched to the front.[8] However, the killings at Frog Lake and the siege of Battleford forced Middleton to change his plan. He sent a large group under Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter north from a second railhead at Swift Current to relieve Battleford and lift the siege.[9] On 1 May, Colonel Otter moved west from Battleford with 300 men. In the early morning of the next day on 2 May, he was confronted by the Cree and Assiniboine force just west of Cut Knife Creek, 40 km from Battleford which would result in the Battle of Cut Knife. The Indigenous force had enormous advantages of terrain, virtually surrounding Otter's troops on an inclined, triangular plain. Cree war chief Fine Day deployed his soldiers successfully in wooded ravines. After about six hours of fighting, Otter retreated. Casualties would have been very high as the militia re-crossed the creek, had not Chief Poundmaker persuaded the Indigenous warriors not to pursue the government troops. Otter's force suffered 8 dead and 14 wounded while Poundmaker's force only suffered 5-6 killed and 3 wounded.[10] The defeat at Cut Knife delayed the lifting of the siege and delayed Middleton's assault on Batoche.[11] After the defeat of the Métis force at the Battle of Batoche and the surrender of Louis Riel to Middleton on May 15. Poundmaker surrendered to General Middleton at Fort Battleford on May 26, 1885.[12]

Aftermath

editCasualties on both sides were relatively light. 3 militiamen, 7 Cree and 2-6 civilians were killed over the course of the siege. Most homes were burned, including the home of Judge Charles Rouleau. Just half a dozen buildings were left standing by the end of the siege.[13] The amount of damage caused during the siege was reported to be upwards of $300,000. Which is equivalent to roughly $10 million in 2023.[14]

Debate

editLike the rest of the North-West Rebellion, the Siege of Battleford has remained a source of debate among historians. Historian Douglas Hill characterized the Cree in his book, The Opening of the Canadian West, as a "war party ... ready to take revenge for a winter of incalculable suffering" who "swooped on Battleford, killing six whites".[15] Canadian historian George Stanley writing on the event indicated that the Cree were not murderous but more haphazard and bumbling stating "they did not appear to have in mind an attack upon the town but were content with prowling around the neighbourhood". In October 2010, Parks Canada stated that they stop using the word "siege" in its posters and programming to describe the "sometimes violent, sometimes tragic events at the frontier community during the Northwest Rebellion."[16]

References

edit- ^ https://nwmp.galtmuseum.com/chapters/the-north-west-rebellion-begins

- ^ Henry Thomas McPhillips (1888), McPhillips' alphabetical and business directory of the district of Saskatchewan, N.W.T.: Together with brief historical sketches of Prince Albert, Battleford and the other settlements in the district, 1888 (p. 53), Prince Albert, NWT: Henry Thomas McPhillips

- ^ http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vol14/no4/page54-eng.asp

- ^ Laurie, Patrick Gammie (April 23, 1885). "Battleford Beleaguered". Saskatchewan Herald. Battleford, Saskatchewan. pp. VOL. V11., No 15.

- ^ "Government House, Battleford". Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ^ William Bleasdell Cameron (1888), The war trail of Big Bear (The Fall of Fort Pitt), Toronto: Ryerson Press (published 1926)

- ^ "The Illustrated War News, 02 May 1885, Page 7, Item Ar00701". J.W. Bengough. Toronto: Grip Print. and Pub. Co. 1885-05-02. p. 7. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ^ a b c Morton (1999), p. 102.

- ^ "North-West Resistance". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.

- ^ "Battle of Cut Knife". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.

- ^ "Battle of Batoche". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.

- ^ "Numbered key, drawn in pen and ink, to accompany the painting "The Surrender of Poundmaker to Major General Middleton at Battleford, on May 26th, 1885"". Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- ^ Mulvaney, Charles Pelham (1885), The history of the North-West Rebellion of 1885 (Otter's March to Battleford) p.109, Toronto: A.H. Hovey & Co, retrieved 2014-04-10

- ^ https://www.sasktoday.ca/highlights/rewriting-history-how-can-fort-battleford-tell-the-truth-7252243

- ^ Hill, Douglas (1967). The Opening of the Canadian West. John Day Company.

- ^ "Cree win war of words over 'siege' of Fort Battleford 125 years ago". The Globe and Mail. 2010-10-21.