This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

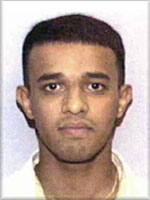

Satam Muhammad Abd al-Rahman al-Suqami (Arabic: سطَّام مُحَمَّدُ عَبْدِ اَلرَّحْمَـٰن السُّقامي, romanized: Saṭām Muḥammad ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān as-Suqāmī; June 28, 1976 – September 11, 2001) was a Saudi terrorist hijacker. He was one of five hijackers of American Airlines Flight 11 as part of the September 11 attacks in 2001.

Satam al-Suqami | |

|---|---|

سطام السقامي | |

| |

| Born | Satam Muhammad Abd al-Rahman al-Suqami June 28, 1976 |

| Died | September 11, 2001 (aged 25) North Tower, New York City, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by plane crash (September 11 attacks) |

| Nationality | Saudi |

| Education | King Saud University |

Al-Suqami had been a law student until he was recruited into al-Qaeda along with Majed Moqed, who was one of the hijackers of American Airlines Flight 77, and traveled to Afghanistan where he would be chosen to participate in the 9/11 attacks.

He arrived in the United States in April 2001. On September 11, 2001, al-Suqami boarded American Airlines Flight 11 and participated in the hijacking of the plane so that it could be crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center as part of the coordinated attacks. He is believed to have perpetrated the first fatality of the attacks in killing passenger Daniel Lewin in the process of hijacking the plane. Al-Suqami died along with everyone else on the plane on impact with the North Tower.

Early life

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

A native of the Saudi Arabian city of Riyadh, al-Suqami was a law student at the King Saud University. While there he joined a (possible)[citation needed] former roommate named Majed Moqed in training for Al-Qaida at Khalden, a large training facility near Kabul that was run by Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi.

Career

editThe FBI says al-Suqami first arrived in the United States on April 23, 2001, with a visa that allowed him to remain in the country until May 21. However, at least five residents of the Spanish Trace Apartments claim to recognize the photographs of both al-Suqami and Salem al-Hazmi, the younger brother of 9/11 hijacker Nawaf al-Hazmi, as living in the San Antonio complex earlier in 2001. However, these residents and several others who claim to have known the hijackers, claim that the FBI photographs of al-Suqami and al-Hazmi are reversed.[2] Other reports conflictingly suggested that al-Suqami was staying with Waleed al-Shehri in Hollywood, Florida, and rented a black Toyota Corolla from Alamo Rent-A-Car agency.[citation needed]

On May 19, al-Suqami and Waleed al-Shehri took a flight from Fort Lauderdale to Freeport, Bahamas where they had reservations at the Princess Resort. Lacking proper documentation however, they were stopped upon landing, and returned to Florida the same day and rented a red Kia Rio from a Avis Car Rental agency.[3]

He was one of nine hijackers to open a SunTrust bank account with a cash deposit around June 2001, and on July 3 he was issued a Florida State Identification Card. Around this time, he also used his Saudi license to gain a Florida drivers' license bearing the same home address as Wail al-Shehri. (A Homing Inn in Boynton Beach). Despite this, the 9/11 Commission claims that al-Suqami was the only hijacker to not have any US identification.[citation needed]

During the summer, al-Suqami and brothers Wail and Waleed al-Shehri purchased one month passes to a Boynton Beach gym owned by Jim Woolard. (Mohamed Atta and Marwan al-Shehhi also reportedly trained at a gym owned by Woolard, in Delray Beach.)

Known as Azmi during the preparations,[4] al-Suqami was called one of the "muscle" hijackers, who were not expected to act as pilots. CIA director George Tenet later said that they "probably were told little more than that they were headed for a suicide mission inside the United States."[5]

September 11 attacks and death

editOn September 10, 2001, al-Suqami shared a room at the Milner Hotel in Boston with three of the Flight 175 hijackers, Marwan al-Shehhi, Fayez Banihammad, and Mohand al-Shehri.

On the day of the attacks, al-Suqami checked in at the flight desk using his Saudi passport, and boarded American Airlines Flight 11. At Logan International Airport, he was selected by CAPPS,[6] which required his checked bags to undergo extra screening for explosives and involved no extra screening at the passenger security checkpoint.[7]

The United Press International noted in March 2002 that an FAA memo, written the day of the attacks, claimed that al-Suqami, seated in 10B, shot passenger Daniel Lewin, co-founder of Akamai Technologies and a former member of the Israeli Sayeret Matkal who was seated in 9B.[8] While based on the frantic phone call received from a stewardess of the flight, the report has been a matter of some controversy, since both the FAA and FBI have strongly denied the presence of firearms or guns smuggled aboard.[citation needed] The FAA claimed that the leaked memo was a "first draft" with incorrect information (such as timeframes), declining to release the final draft of the memo which was said to lack any reference to discharging ammunition on the flight.[8] The 9/11 Commission speculated that al-Suqami stabbed Lewin so he could not prevent Atta and al-Omari, whose row was in front of his own, from hijacking the flight.[9] In 2004, further analysis of flight attendant Betty Ong’s phone call to American Airlines reservations confirmed that al-Suqami slashed Lewin's throat; however, it is unclear whether Lewin was stabbed for attempting to intervene in the hijacking, or to frighten other passengers and crew into compliance because Lewin was seated directly in front of al-Suqami.[10][11]

Passport discovery

editThe passport of al-Suqami was found by a passerby in the vicinity of Vesey Street,[12] before the towers collapsed.[13] (This was mistakenly reported by many news outlets to be Mohamed Atta's passport.)[citation needed][14] A columnist for the British newspaper The Guardian expressed incredulity about the authenticity of this report,[15] questioning whether a paper passport could survive the inferno unsinged when the black boxes of the plane were never found. According to testimony before the 9/11 Commission by lead counsel Susan Ginsburg, his passport had been "manipulated in a fraudulent manner in ways that have been associated with al Qaeda."[13] Passports belonging to Ziad Jarrah and Saeed al-Ghamdi were found at the crash site of United Airlines Flight 93 as well as an airphone.[16]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Joe Conger (January 10, 2001). "2 hijackers identified as former S.A. residents". mysanantonio.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2003.

At least five sources tell KENS 5, two of the men, Satam al-Suqami and Salem al-Hazmi, lived at the Spanish Trace Apartments on the North Side earlier this year

- ^ "911 Commission Report, section 7.4 'Final Strategies and Tactics', page 241". Archived from the original on July 1, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ Videotape of recorded will of Abdulaziz al-Omari and others

- ^ "Sept. 11 Hijacker Made Test Flights". CBS. October 9, 2002. Archived from the original on September 27, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2004.

- ^ "9/11 Commission Report (Chapter 1)". July 2004. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2006.

- ^ "The Aviation Security System and the 9/11 Attacks - Staff Statement No. 3" (PDF). 9/11 Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2006.

- ^ a b "UPI hears..." United Press International. March 6, 2002. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ "'We Have Some Planes'". National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. July 2004. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ^ "Excerpt: A travel day like any other — until some passengers left their seats". July 23, 2004. Archived from the original on November 19, 2011.

- ^ Nickisch, Curt (September 8, 2011). "Cambridge Co. Keeps Founder's Spirit Alive After 9/11". WBUR 90.9 Boston's National Public Radio News Station. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ "Ashcroft says more attacks may be planned". CNN. September 18, 2001. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ a b 9/11 Commission hearings, January 26, 2004, Opening staff statement, Susan Ginsburg Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ YouTube. youtube.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ Karpf, Anne (March 19, 2002). "Uncle Sam's lucky finds". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Remembering September 11th". The Boston Globe. September 11, 2009. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

External links

edit