Sarracenia flava, the yellow pitcherplant,[2] is a carnivorous plant in the family Sarraceniaceae. Like all the Sarraceniaceae, it is native to the New World. Its range extends from southern Alabama, through Florida and Georgia, to the coastal plains of southern Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina. Populations also exist in the Piedmont, Mendocino County, California[3] and mountains of North Carolina.

| Yellow pitcher plant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Sarraceniaceae |

| Genus: | Sarracenia |

| Species: | S. flava

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sarracenia flava | |

| |

| Sarracenia flava range | |

Like other members of the genus Sarracenia, the yellow pitcher plant traps insects using a rolled leaf, which in this species is a vibrant yellow in color, and up to over a meter (3 ft) in height[4] (although 50 cm, 20" is more typical). The uppermost part of the leaf is flared into a lid (the operculum), which prevents excess rain from entering the pitcher and diluting the digestive secretions within. The upper regions of the pitcher are covered in short, stiff, downwards-pointing hairs, which serve to guide insects alighting on the upper portions of the leaf towards the opening of the pitcher tube. The upper regions are also brightly patterned with flower-like anthocyanin markings, particularly in the varieties S. flava var. rugelii and S. flava var. ornata: these markings also serve to attract insect prey. The opening of the pitcher tube is retroflexed into a 'nectar roll' or peristome, whose surface is studded with nectar-secreting glands. The nectar contains not only sugars, but also the alkaloid coniine (a toxin also found in hemlock), which probably intoxicates the prey. Prey entering the tube find that their footing is made extremely uncertain by the smooth, waxy secretions found on the surfaces of the upper portion of the tube. Insects losing their footing on this surface plummet to the bottom of the tube, where a combination of digestive fluid, wetting agents and inward-pointing hairs prevent their escape. Some large insects (such as wasps) have been reported to escape from the pitchers on occasion, by chewing their way out through the wall of the tube.

In spring, the plant produces large flowers with 5-fold symmetry. The yellow petals are long and strap-like, and dangle over the umbrella-like style of the flower, which is held upside down at the end of a 50 cm, 20" long scape. The stigma of the flower are found at the tips of the 'spokes' of this umbrella. Pollinating insects generally enter the flower from above, forcing their way into the cavity between the petals and umbrella, and depositing any pollen they are carrying on the stigmata as they enter. The pollinators generally exit the flower, having been dusted with the plant's own pollen, by lifting a petal. This one-way system helps to ensure cross pollination.

In late summer and autumn, the plant stops producing carnivorous leaves, and instead produces flat, non-carnivorous phyllodia. This is probably an adaptation to low light levels and insect scarcity during the winter months, and shows clearly the cost of carnivory.

The yellow pitcher plant is easy to cultivate, and is one of the most popular carnivorous plants in horticulture. The yellow pitcher plant readily hybridises with other members of the genus Sarracenia: the hybrids S. x catesbaei (S. flava × S. purpurea) and S. moorei (S. flava × S. leucophylla) are found in the wild, and are also popular amongst collectors.

-

Pitcher mouth with operculum

-

Flower

-

A "pitcherplant meadow" in the Florida panhandle, with mixed varieties of Sarracenia flava: var. rugelii, var. ornata, and var. rubricorpora

References

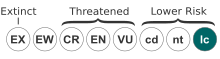

edit- ^ Schnell, D.; Catling, P.; Folkerts, G.; Frost, C.; Gardner, R.; et al. (2000). "Sarracenia flava". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T39715A10259287. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T39715A10259287.en. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Sarracenia flava". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ iNaturalist.org "Sarracenia flava".

- ^ Graham, D.L. 1997. "Reflections and suggestions from 1996" (PDF). Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 26(4): 118–120.

- McBride, James (February 1819), Thomson, Thomas (ed.), "Power of the Sarracenia Adunca to entrap Insects", Annals of Philosophy, vol. XIII, no. LXXIV, p. 149, retrieved 27 April 2015

- Mody, NV; Henson, R; Hedin, PA; Kokpol, U; Miles, DH (1976). Isolation of insect paralyzing agent coniine from Sarracenia flava. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 32(7): 829–830. doi:10.1007/BF02003710

- N.C. State University reference

- Schnell, D.; Catling, P.; Folkerts, G.; Frost, C.; Gardner, R.; et al. (2000). "Sarracenia flava". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T39715A10259287. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T39715A10259287.en.