Sam Gilliam (/ˈɡɪliəm/ GHIL-ee-əm; November 30, 1933 – June 25, 2022) was an American abstract painter, sculptor, and arts educator. Born in Mississippi, and raised in Kentucky, Gilliam spent his entire adult life in Washington, D.C., eventually being described as the "dean" of the city's arts community.[1] Originally associated with the Washington Color School, a group of Washington-area artists that developed a form of abstract art from color field painting in the 1950s and 1960s, Gilliam moved beyond the group's core aesthetics of flat fields of color in the mid-60s by introducing both process and sculptural elements to his paintings.[2][3]

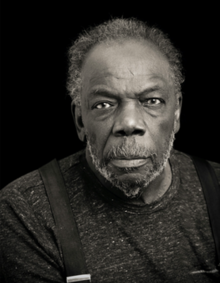

Sam Gilliam | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 30, 1933 Tupelo, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | June 25, 2022 (aged 88) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Louisville |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Double Merge (Carousel I and Carousel II) (1968) Seahorses (1975) Yves Klein Blue (2017) |

| Movement | Washington Color School |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3, including L. Franklin and Melissa |

Following early experiments in color and form, Gilliam became best known for his Drape paintings, first developed in the late 60s and widely exhibited across the United States and internationally over the following decade.[4] These works comprise unstretched paint-stained canvases or industrial fabric without stretcher bars that he suspended, draped, or arranged on the ground in galleries and outdoor spaces. Gilliam has been recognized as the first artist to have "freed the canvas" from the stretcher in this specific way, putting his paintings in conversation with the architecture of their settings.[5] In contemporary art, this contributed to collapsing the space between painting and sculpture and influenced the development of installation art.[6] While this became his signature style in the eyes of some critics and curators, Gilliam mostly moved on from his Drape paintings after the early 1980s, primarily returning to the form for several commissions and a series of late-career pieces, usually created with new techniques or methods that he was exploring in his other work.[7]

He produced art in a range of styles and materials, exploring the boundaries between painting, sculpture, and printmaking. Other well-known series of works include his early Slice paintings begun in the mid-1960s, often displayed with custom beveled stretcher bars that make the paintings protrude from the wall;[8] his Black Paintings from the late 1970s, which Gilliam created with thick layers of black impasto over collaged forms;[9] and a series of monumental painted metal sculptures, developed beginning in the 1980s and 1990s for several public commissions.[10]

After early critical success, including becoming the first African American artist to represent the United States in an exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1972, Gilliam's career saw a period of perceived decline in attention from the art world in the 1980s and 1990s, although he continued to widely exhibit his work and completed numerous large-scale public and private commissions.[11] Starting in the mid-2000s, his work began to see renewed national and international attention, and his contributions to contemporary art were reexamined and reevaluated in several publications and exhibitions.[7] His work has since been described as lyrical abstraction.[12] Late-career milestones included creating a work for permanent display in the lobby of the then-newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016, and exhibiting for a second time at the Venice Biennale in 2017.[1]

Early life and education

editSam Gilliam Jr. was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, on November 30, 1933,[7] the seventh of eight children born to Sam Gilliam Sr. and Estery Gilliam.[8] The Gilliam family moved to Louisville, Kentucky, in 1942.[13] Gilliam said that his father "did everything," working variously as a farmer, janitor, and deacon, in addition to being a hobbyist carpenter;[14] his mother was a school teacher, cared for the large family,[7] and was an active member of the neighborhood sewing group.[13] At a young age, Gilliam wanted to be a cartoonist and spent most of his time drawing[15] with encouragement from his mother.[16] As an adult, Gilliam recalled that creativity was an essential part of his home life as a child: "Almost all of my family members used their hands to create ... In this atmosphere of construction, I too began to flourish."[13] Throughout his middle and high school education he participated in school-sponsored specialized art programs.[7] He attended Central High School in Louisville, and graduated in 1951.[17]

After high school, Gilliam attended the University of Louisville and received his B.A. in painting in 1955 as a member of the second admitted class of black undergraduate students.[7][18] While in school he studied under professors including Eugene Leake, Mary Spencer Nay, and Ulfert Wilke, eventually working as Wilke's studio assistant; Gilliam became interested in Wilke's collection of woodcut prints, African sculpture, and art by Paul Klee.[19] Wilke helped spark Gilliam's growing interest in German Expressionists like Klee and Emil Nolde, and encouraged him to pursue a similar style.[20] Gilliam later said that Wilke would often refuse to let him use oil paint in class because "I treated the canvas with too much respect;"[21] Wilke had Gilliam work with watercolors to learn to release some level of control in the painting process and allow for serendipity in the final product, as the medium can spread somewhat uncontrollably when applied.[22][23]

In 1954 he was introduced to Dorothy Butler after seeing her on the bus, and the two began dating.[24] He staged his first ever solo art exhibition in 1956 at the university, the year following his graduation.[24] From 1956 to 1958 Gilliam served in the United States Army, stationed in Yokohama.[24] While in Japan he visited Frank Lloyd Wright's Imperial Hotel prior to its demolition in 1967,[24] learned about the Gutai Art Association, and was introduced to the work of Yves Klein at an exhibition in Tokyo.[25] Gilliam later said that seeing Klein's work in particular "had an effect on me, and I thought about making art beyond the interiors that it is usually presented in, about making art more in the outside world."[25] He was honorably discharged from the Army with a rank of specialist 3rd class.[24]

He returned to the University of Louisville in 1958 and received his M.A. in painting in 1961, studying under Charles Crodel.[26][24] Most of Gilliam's art during this period was expressionistic figurative painting bordering on abstraction that art historian Jonathan P. Binstock[note 1] has described as "typically dark and muddy in tone."[28] He was inspired in large part during this period by several artists associated with the Bay Area Figurative Movement, including Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, and, in particular, Nathan Oliveira, whose work he had been introduced to by Wilke, his undergraduate professor, and by seeing the exhibition 2nd Pacific Coast Biennial, which traveled in 1958 to Louisville's Speed Art Museum.[29][28] Gilliam's thesis, inspired by this group of artists working in a mode that embraced chance and accidents, was not well received by his advisor Crodel,[30] who believed it was "too subjective,"[21] but Gilliam still viewed Crodel as an important influence in the development of his work.[30] Gilliam specifically credited Crodel for instilling in him both a respect for the relationship between students and teachers as well as the importance of the study of art history.[30] While attending graduate school he also befriended painter Kenneth Victor Young.[31] Gilliam served on the executive board of the local chapter of the NAACP as a youth advisor and helped organize numerous sit-ins, pickets, and protests against segregation, often in conjunction with local Unitarian churches.[32] He was arrested and jailed on several occasions for non-violent civil disobedience.[21]

Butler earned her master's degree from Columbia while Gilliam remained in Louisville, and he traveled to New York to visit her often,[32] where he also became interested in work by Hans Hofmann, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko.[33] They married in 1962 and moved to Washington, for Butler's new job as the first African-American woman reporter for The Washington Post;[note 2] Gilliam would spend the rest of his life living and working in D.C.[9]

Life and career

edit1960s

editOn arriving in Washington in 1962, Gilliam and Butler rented an apartment in the Adams Morgan neighborhood.[24] Gilliam tried to enroll in painting courses at American University under artist Robert Gates, a painting professor interested in the same Bay Area Figurative style, but Gates declined, saying Gilliam would not gain much from being his student.[34] Gilliam was also turned down for a teaching position at Howard University by art department chair James Porter; according to Gilliam, Porter said he was "too 'passionate' a painter to be worried about teaching," and recommended Gilliam teach at a local high school instead to allow for more time to make and exhibit art.[34] Binstock[note 1] suggested that Porter's rejection of Gilliam may have also been due to Gilliam's abstract figurative style clashing with Porter's view of the school's direction, during the era's cultural shifts and social movements, including the Black power movement, which were manifesting in art as a clear, declarative, and often overtly political aesthetic: "Gilliam's somewhat ethereal and apparently raceless figures may have seemed irrelevant to Porter."[34] Gilliam followed Porter's advice – and that of his college professors[18] – to become a high school teacher, teaching art at D.C.'s McKinley Technical High School for five years, eventually becoming close with Porter as a friend and colleague.[34] As an art teacher, Gilliam could dedicate time to his own art on the weekdays reserved for his students' academic classes,[18] renting a painting studio at 17th and Q St NW near Dupont Circle.[35][36]

In 1963 he presented his first solo exhibition in the city at The Adams Morgan Gallery, showing a selection of figurative and representational oil and watercolor paintings from his first early series, Park Invention, which depicted views in nearby Rock Creek Park.[37] Although unaware of the abstract art movements in Washington when he arrived in the city, Gilliam was introduced to what had recently become known as the Washington Color School, a loose collection of artists making abstract color field painting, historically centered in Dupont Circle.[38] Thomas Downing, the only core member of the Washington Color School's first generation still living in the city, attended the exhibition opening and quickly became a supporter and mentor of Gilliam.[23] Downing told Gilliam that the best work in the exhibition was the single fully abstract watercolor painting, a note of feedback that led Gilliam to more wholly embrace a style of painting loosely.[33][23] Gilliam began to work wholeheartedly in abstraction, continuing to travel to New York and researching notable contemporary artists, experimenting in depth with their theories, styles, and methods in order,[33] in his words, "to get away from the look of so many painters who were capable of opening my eyes."[39] He said this technique of mimicking others' styles to develop his own first occurred when he realized that the composition of a figurative work in progress resembled the structure of a painting by abstract expressionist artist Hans Hofmann, marking the moment he transitioned completely to abstraction.[40]

Gilliam and Butler moved to a rented house in the Manor Park neighborhood soon after Gilliam's first exhibition.[36] Once his first year of teaching at McKinley ended in 1963, he didn't secure a summer job and was able to spend several months exploring different styles of abstraction, beginning to embrace a style of distinct geometric shapes.[36] In August 1963 Gilliam and Butler participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech.[41] Although Gilliam had been deeply engaged as an activist in college, critic Vivien Raynor would later write that he had "emerged disenchanted," feeling that "the sum total of his activism had amounted to little more than gaining political honors for others."[21] The 1963 March on Washington was Gilliam's last major protest for social change; he had come to view art-making, according to Binstock,[note 1] as "at least as important as politics,"[42] a major departure from both the general outlook in Washington, a political capital, and from the prevailing attitude of some black activists and artists who saw value in art as a tool for political action and message-making rather than as intrinsically worthwhile outside of politics.[41][43][42] In 1993 Gilliam recalled that during this period activist Stokely Carmichael had brought him and several other black artists together to tell them, "You’re Black artists! I need you! But you won’t be able to make your pretty pictures anymore."[44] Despite this general mood among many of his contemporaries, Gilliam committed himself to exploring formalist abstraction instead of clearly legible figuration.[42] Reflecting on this period two decades later, critic John Russell wrote that Gilliam "stood firm for his own kind of painting at a time when abstract art was said by some to be irrelevant to black American life."[45]

In December 1963 Gilliam was hospitalized in Louisville, in connection with anxiety he felt about his artistic career;[46] he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and prescribed lithium.[47][48]

Early color field and hard-edge abstraction

editIn 1964, Gilliam began developing a series of paintings that experimented with hard-edge and color field styles, with precise geometric fields of color similar to those of Washington Color School painters like Downing, Gene Davis, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Noland,[39] who had been influenced in turn by the soak-stain painting techniques of Helen Frankenthaler.[49] Binstock has argued that Gilliam's work was informed in large part by Downing and his relationship to the formation of the movement; unlike Louis and Noland, Downing had not yet been championed by art critic Clement Greenberg,[50] whose praise had been instrumental in elevating the Washington School painters.[51] Downing believed the movement's strengths were broader than Greenberg's focus - the importance of the flatness of the colored shapes - and he encouraged Gilliam and others to embrace a more expansive definition of abstraction.[52] While the two were close and would often have the other over for dinners with their wives, Gilliam characterized their relationship - and his relationship with other artists[53] - as competitive, later saying that Downing "didn't influence me, he was someone that I had to beat, to compete with, which meant we hung out together."[54] Downing also introduced Gilliam to methods and materials used by the cohort, such as how to work with Magna acrylic resin paint which can soak into canvas rather than layering on top of it, along with a water-tension breaker, the group's so-called "secret ingredient."[55] Gilliam primed his canvases with the water-tension breaker, to "open the pores" of the canvas, letting him mix paint colors as they soaked in, instead of mixing on a palette, giving them a translucent appearance.[55] Gilliam showed his early hard-edge experiments in 1964 in his second solo exhibition at The Adams Morgan Gallery, his first show of exclusively abstract art. The same year he also began teaching in the summers at the Corcoran Gallery of Art.[32]

Gilliam went through several distinct stages working in this style, starting with a series of solid color field paintings that were bisected by diagonal stripes of alternating color, separated by thin lines of bare canvas,[56] inspired by Gene Davis' extensive use of the stripe motif and by Morris Louis' final series of striped abstractions.[56] Gilliam's stripe paintings were followed by pennant paintings, a series that combined the striated stripe format with the style of Kenneth Noland's geometric chevron paintings.[56] Paintings by Gilliam from this period of hard-edge abstraction include Shoot Six, which showcased how he was moving beyond the Washington School's core styles, as the distinct regions of colors blend together in the lower-right corner.[56]

In 1965, Gilliam showed his new hard-edge paintings in a solo exhibition at Jefferson Place Gallery, one of Washington's most well-known commercial galleries in the 1960s.[56] Downing had introduced him to Nesta Dorrance, the owner of the gallery, and suggested Gilliam for a group exhibition, but Dorrance invited him to exhibit solo.[56] Gilliam only sold one painting from the exhibition, which did not see much critical attention or success,[56] but his relationship with the gallery continued for another eight years.[15]

Despite some unenthusiastic reviews, this series of works cemented Gilliam in the eyes of critics as one of the inheritors of the Washington Color School.[57] Among his first media coverage was a profile in the debut issue of Washingtonian in October 1965, which described him as "one of the younger (31), less touted 'Washington Color Painters.'"[58][56] In 1966, his hard-edge paintings were included in the group exhibition The Hard Edge Trend at Washington's National Collection of Fine Arts.[59] Critic Andrew Hudson negatively reviewed that work in the show for The Washington Post,[note 2] calling his paintings "poorly executed" and writing, "One wonders whether Gilliam wants his colors to run into one another or not, and why he doesn't try giving up sharp edges and defined color areas and see what happens."[60] Writing in The Washington Star[note 3] in 1966, critic Benjamin Forgey described Gilliam as "one of the minor followers in the wake of the color school."[61] Gilliam later said that the association with the Washington School was an important milestone that encouraged him to continue working.[62]

This early media coverage also coincided with a few group exhibitions outside of Washington that helped raise his national profile, including two exhibitions in Los Angeles: Post-Painterly Abstraction (1964) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, curated by Greenberg;[3] and The Negro in American Art (1966) at UCLA, a historical survey of African-American art curated by James Porter that also included sculptor Mel Edwards, and led Edwards and Gilliam to become friends and colleagues.[63]

Fluid abstractions, beveled Slice paintings, and Phillips exhibition

editTo create his hard-edge paintings, Gilliam would tape over sections of unprimed canvas and use a brush or sponge to stain the uncovered portions with paint.[64][65] In 1966 he began to remove the tape before the paint had dried, allowing the colors to run fluidly together over the entire surface, as in the watercolor work Downing had first admired in 1963.[66]

After seeing Gilliam's earlier hard-edge abstractions and works in this new transitional style, art collector Marjorie Phillips invited him to present his first solo museum exhibition in the fall of 1967 at The Phillips Collection in Dupont Circle.[67] Gilliam was able to leave his teaching position at McKinley to focus on his painting in the run-up to the exhibition, thanks to an individual artist's grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA),[68] which he also used to purchase a home in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood.[67] Gilliam and Butler were expecting their third child at the time and had been struggling to make ends meet despite both achieving professional success,[67] with Gilliam painting almost exclusively in the basement of their Manor Park home as he could no longer afford a studio after their first child was born.[35][36] Gilliam also began teaching at the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1967.[69]

In preparing for the exhibition, Gilliam revisited his fluid experimentations from the previous weeks and discovered a study he later titled Green Slice, a watercolor work on washi from early 1967 that he said he couldn't remember making,[70] an indication of the speed at which he was producing studies and experiments.[71] This was a slightly crumpled watercolor in soft blues, greens, and rose, apparently made by folding the work over itself in places immediately after applying the paint, creating several vertical "slices" emanating from the bottom edge of the painting.[72] After seeing a posthumous exhibition of Morris Louis's work at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art (WGMA), Gilliam came to view Green Slice through the lens of Louis's brushless painting technique.[73] He began creating paintings without a predetermined structure like his earlier abstractions, instead focusing on the physical process of painting, working quickly to pour watered-down acrylic over canvases laid on the floor, moving the pools of paint around and into each other by physically manipulating the canvases, allowing a composition to appear by both improvisation and chance.[74][75][70] This resulted in works like Red Petals, with circles of dark red spreading from the points where Gilliam allowed the paint to pool, and traces of fluid movement where the different paints ran together across the canvas.[76][70]

At this point Gilliam created and formalized his Slice series. Continuing to stain and soak his canvases with thinned acrylic paint while they lay on the floor, he began to mix metals like ground aluminum into his paint and started physically splashing the canvas as well.[77][78] He drew on the approach of Green Slice by folding the canvases on top of themselves to create clear "slices" and bisected pools of color throughout the compositions before crumpling them in piles to dry, sometimes splashing additional paint on while they lay drying, adding several elements of chance into the final image.[77][78] Finally, he built custom beveled stretcher bars for the Slice canvases; he would alternately stretch the canvases with the stretchers oriented either toward the wall or toward the viewer.[77][79] When oriented toward the wall, the bevel gave the canvas the appearance of floating, disembodied from any physical support when viewed from the front; when oriented toward the viewer, the bevel support was visible under the canvas, making the works appear like painted sculptural reliefs with angled edges.[80][79] This use of beveled stretchers was inspired by the chamfered fiberglass and Plexiglas painting constructions of Ron Davis, after being introduced to them by his friend Rockne Krebs:

"I stole it." [laughter] "I stole it from Ron Davis. In fact, Rockne, who was always helping me steal things, was telling me things I ought to do. He pointed out for us how Ron Davis was using the Plexiglas and allowing it to float right in space by putting it on this beveled edge... I lifted it in order to try it, and it worked. And then when I flipped it over, it worked even better."

For his exhibition at The Phillips Collection in 1967, Gilliam exhibited six Slice paintings made that year, stretched over bevels oriented toward the wall, along with Red Petals, Green Slice, and three additional watercolors.[80] The museum purchased Red Petals, marking Gilliam's first inclusion in a museum collection,[81] and he followed up this exhibition with another show of Slice paintings at Jefferson Place Gallery before the end of the year.[82] He began increasing the size of his Slice paintings, eventually reaching a size that could fill entire walls.[78] He would later say that in the 1960s he felt "a need for scale,"[78] which he referred to as "both practical and psychological."[83] Gilliam exhibited more beveled Slice paintings at the Byron Gallery in June 1968, his first solo show in New York, including the 30 × 9 ft painting Sock-It-to-Me,[84] which he stretched at that size as a response to the width of the gallery wall.[83] Sock-It-to-Me was so heavy it destroyed the wall, and Gilliam said that the gallery owner temporarily shut off the lights at the opening as a gesture to show that he believed the work was too large to be sellable.[85][83] After seeing this exhibition, artist William T. Williams began a long-term correspondence with Gilliam.[86]

The exhibition at The Phillips was lauded by regional art critics, many specifically praising the Slice paintings and Gilliam's evolution beyond the core tenets of the Washington Color School.[74][87] Benjamin Forgey of The Washington Star[note 3] wrote that Gilliam had begun to let his paintings "go soft" as opposed to the hard geometry of the Washington School, and described the new work as showing "the effervescence of an artist experiencing a new liberation;"[87] while Andrew Hudson, writing in Artforum in 1968, described Gilliam as "a former follower of the Washington Color School" who had "emerged as having broken loose from the 'flat color areas' style, and as an original painter in his own right."[88] Binstock argued that the critics were recognizing Gilliam's artistic talent and potential while at the same time attempting to establish the early Washington School style as a movement of the past, to encourage more local innovation like Gilliam's to cement Washington's role as an art center.[84] Gilliam's solo show in New York was less noticed,[84] but still received praise in Artforum from critic Emily Wasserman who wrote positively about the dimensional qualities of the color in his Slice paintings, which she termed "color as matter."[89]

Support from Walter Hopps and early Drape paintings

editIn 1966, curator Walter Hopps came to work for the Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank;[73] in 1967 he became acting director of the WGMA, where he worked to integrate his policy ideas, refocusing the institution on local and regional living artists and building an outreach program oriented in part toward D.C.'s large black community,[90] soon offering Gilliam a space in the WGMA's new artist-in-residence program.[91] This offer in December 1967, just after Gilliam's Phillips exhibition - of a $5,000 stipend and studio space in the institution's new workshop downtown with a $50,000 operations budget - led him to continue painting full time instead of returning to teaching, but the workshop did not open until April 1968 and Gilliam did not receive the stipend until June.[92] Looking back on this decision, Gilliam said, "I survived at least six months just on the promise of $5,000," and "It took a lot of guts."[92] When the WGMA workshop opened in 1968, Gilliam shared the space with Krebs; other artists in the program included printmaker Lou Stovall,[92] who would become Gilliam's long-term colleague and collaborator.[93]

During this period between late 1967 and mid-1968, Gilliam started experimenting with leaving his paintings unstretched, free of any underlying wooden support structure, a technique that developed into what he would call his Drape paintings.[94] Following a similar painting process to his Slice works by soaking, staining, and splashing unstretched canvases laid on the ground before leaving them crumpled and folded to dry, he began to use rope, leather, wire, and other everyday materials to suspend, drape, or knot the paintings from the walls and ceiling in his basement and the WGMA workshop after they dried, instead of attaching them to a stretcher.[94][95][96] As with the folding of the wet canvas that he had begun with his Slice paintings and continued with his Drapes, the gesture of draping left a large element of the artwork's visual presence to be determined by chance - as the canvas folds or bunches unpredictably - but, unlike the Slice paintings, the form of each Drape is also determined in part by the specific layout of the space the work hangs in, and by the actions of the person installing the piece.[97][98] The exact inspirations behind the Drape paintings are unclear, as Gilliam offered multiple explanations throughout his life.[1] Among the most-cited origin stories is that he was inspired by laundry hanging on clotheslines in his neighborhood in such volumes that the clotheslines had to be propped up to support the weight, an explanation he told ARTnews in 1973.[99] He offered several different explanations later in his life,[100][101] and eventually directly refuted the laundry origin story.[1]

Gilliam first publicly exhibited his Drape paintings in late 1968 in a group show at the Jefferson Place Gallery,[102] which included works like Swing.[103] The same year, Hopps facilitated the merger of the WGMA with the Corcoran Gallery, becoming director of the newly combined institution and inviting Gilliam, Krebs, and Ed McGowin to present new work together at the Corcoran.[92] The 1969 exhibition, Gilliam/Krebs/McGowin presented ten of Gilliam's largest and most immersive Drape works up to that point, including Baroque Cascade, a 150 ft long canvas suspended from the rafters in the Corcoran's two-story atrium gallery, and several separate 75 ft long wall-sized canvases draped on the sides of the gallery.[104] Baroque Cascade in particular was broadly acclaimed by critics as marking a singular achievement in combining painting and architecture to explore space, color, and shape,[105] with LeGrace G. Benson writing in Artforum that "every visible and tactile and kinetic element was drawn into an ensemble of compelling force;"[106] Forgey later called the exhibition "one of those watermarks by which the Washington art community measures its evolution."[1] He also began testing new fabrics for the Drape paintings, working with linens, silks, and cotton materials to find the best canvas for his soaking and staining techniques.[106]

Gilliam was neither the first or the only artist to experiment with unstretched painted canvases and fabrics during this era, but he was noted for taking the method a step further than his contemporaries, situating each piece differently depending on the space it was being presented in and working on a much greater scale to create an immersive experience for the viewer that blended architecture and sculpture with painting, a development that would influence the burgeoning field of installation art.[107][108] Conceptually, the Drape paintings can also be understood in the frameworks of site-specificity or site-responsiveness,[109] along with art intervention and performance art,[110] all themes explored by a range of other artists cited by Gilliam as influences at the time, from early land artists to the happenings of Allan Kaprow.[97] Because Gilliam's particular form of unstretched canvas went beyond other artists' experiments and emerged with conceptual parallels to an array of rising art movements, critics and art historians identified him as a key pioneer in contemporary art of the era,[111][112] and he has been cited as the "father of the draped canvas."[9]

In 1969 Gilliam presented several large Slice paintings in the group exhibition X to the Fourth Power, alongside work by William T. Williams, Mel Edwards, and Stephan Kelsey, at the newly established Studio Museum in Harlem.[113][114] Afterward, Gilliam, Edwards, and Williams – all African-American artists working in abstraction – became closer, and went on to stage exhibitions as a trio multiple times in the 1970s.[115][116]

Williams had organized the exhibition of exclusively abstract art at a moment of increasing disagreement between black artists who saw art-making of any kind as a liberatory act in itself, and those who viewed abstract aesthetics as anti-radical and irrelevant to black audiences,[43] a debate that was playing out among the Studio Museum's staff and supporters.[117][118] Several reviews of the exhibition focused on this perceived tension.[118][119] Around the same time, Gilliam introduced explicit references to politics and current events in the titles of several Slice paintings, including April, April 4, and Red April, all from his Martin Luther King series; the dates that serve as the names of each painting in this series correspond with King's assassination in April 1968, the nationwide riots and uprisings following King's murder, and the Washington-specific civil unrest which was among the most intense in the country and left large swaths of the city burned, particularly in neighborhoods close to Gilliam's home in Mount Pleasant and the WGMA studio that he had begun to use the same month.[120] He later explained that the paintings were not meant to be understood as abstract portraits of King:[121]

"[The titles] do not change the meaning of the painting for me. Rather, they help me to interpret and to clarify times and concepts. Figurative art doesn't represent blackness any more than a non-narrative media-oriented kind of painting, like what I do. The issue is the works ... deal with metaphors that are heraldic. I must have made some six or seven Martin Luther King paintings. The paintings are about the sense of a total presence of the course of man on earth, or man in the world."

— Sam Gilliam, in Joseph Jacobs, Since the Harlem Renaissance: 50 Years of Afro-American Art (1985)[122]

1970s

editNew Drape forms, national and international success, printmaking

editFollowing the critical success of his early Drapes, Gilliam was invited to present his work at a number of museums and galleries in the early and mid-1970s, both creating new Drape installations and re-installing previous ones.[123] In 1970, Gilliam was also hospitalized for anxiety and depression for a second time.[46] In April 1971, he withdrew from a group exhibition of contemporary African-American art at New York's Whitney Museum in solidarity with a boycott organized by the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC).[124] Gilliam and other artists were frustrated with the museum, which had organized the exhibition in response to earlier BECC protests over the lack of black artists in the Whitney's programming, because they believed the curator had made only cursory attempts to contact established black curators and scholars of African-American art to help shape the exhibition.[124][125]

He continued to create larger and more immersive Drapes throughout this period,[68] embellishing the paintings' environments with metal, rocks,[126] wooden beams, ladders,[127] and sawhorses, sometimes draping or piling the canvases over the objects instead of suspending them from above.[128] "A" and the Carpenter I and Softly Still both comprised crumpled, unstretched stained canvases with sewn patchwork elements, arranged on top of wooden sawhorses placed on the ground.[126] These two pieces typified what Binstock[note 1] termed a "drop-cloth aesthetic," describing both the new textures Gilliam explored in his canvases, which looked like the tarps used to protect the floor in an artist's studio, and the resemblance of the installations to studios full of works in progress.[128] In the early 1970s he also began using industrial polypropylene fabrics for his Drapes instead of and in addition to canvas; this material is stronger and more lightweight than traditional woven fabrics and Gilliam found it to be better suited to absorbing pigment in combination with water-tension breaker.[129]

After the WGMA workshop space closed in 1971, Gilliam and Krebs were allowed to continue using the remaining operations budget to fund their personal studios, supporting them for an additional seven years.[92]

In November 1971, he staged a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, his first solo museum show in New York,[69] presenting Carousel Merge, a nearly 18 ft long canvas that hung from the ceiling onto a ladder the artist placed in the gallery and stretched around a corner between two different spaces,[130][131] along with a set of watercolors and several wall-based Drapes from his Cowls series.[132][133] Gilliam's Cowls, smaller variations on the Drape format, each comprise a stained and painted canvas hung on the wall by a single point via a cowl-like series of folds at the top of the canvas, oriented variously angled up or down and radiating into the rest of the canvas.[134]

In the early 1970s Gilliam began extensively incorporating printmaking techniques and paper into his practice, making his first prints in collaboration with Stovall in 1972.[69] Stovall described Gilliam in the print shop as "one of the few artists who could work quickly and surely enough to invent an interesting format on the spot."[135] While still creating new immersive Drape installations for a series of commissions and exhibitions, he also returned to the format of the rectangular stretched canvas around this time, beginning with his Ahab series; he described this as his first attempt to create a "perfect" white composition.[136] These works, begun by staining canvases with color and stretching them over beveled wood similar to his Slice paintings,[137] were then covered in layers of white acrylic glaze and flocking applied with lacquer thinner, before being placed in custom aluminum frames made in collaboration with Stovall.[138]

Hopps remained a champion of Gilliam's work during this period,[92] telling The Washington Post[note 2] that he believed Gilliam's Drapes "break away from painting's traditional imitation of the panel picture by dealing with the palpable, soft qualities of the canvas."[139] He recommended Gilliam to other curators for his first international exhibitions including the 1969 Triennale-India at the Lalit Kala Akademi,[92] and introduced him to gallerist Darthea Speyer, who staged Gilliam's first European exhibition in 1970 at her gallery in Paris and became his longest continuous art dealer.[69] Hopps also included him in a group exhibition for the 1972 American pavilion organized by the Smithsonian at the Venice Biennale.[25] Gilliam exhibited three earlier wall-sized Drape paintings Genghis I, Light Depth, and Dakar,[140] and he lived in the pavilion for a week to install the works.[141] His paintings were shown in Venice alongside the work of Diane Arbus, Ron Davis, Richard Estes, Jim Nutt, and Keith Sonnier.[142] Gilliam was the first African-American artist to represent the United States in a show at the Biennale.[8][143]

Autumn Surf, Dark as I Am, and collage

editIn 1973 he was featured in the group exhibition Works in Spaces at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, completely filling the gallery space with Autumn Surf, a 365 ft long[129] polypropylene Drape that dropped from the ceiling before spreading completely around the room to create an angled bay that allowed viewers to "enter" the piece.[127] He installed several ceiling-height vertical oak beams around the gallery with horizontal beams attached lower down, building an armature from which he draped portions of the painting;[127] the beams also served as anchors for a series of cords, ropes, and pulleys to further suspend other portions of the painting, creating tall wave-like forms.[123] Art historian Courtney J. Martin has called it "a hinge in Gilliam's practice, showing how his work matured up to that moment,"[144] and said the installation spoke to "his desire to work in space;"[145] Binstock[note 1] has described the work as "arguably the preeminent example" of Gilliam's Drapes.[123] Gilliam re-staged and recycled the painted polypropylene from Autumn Surf multiple times over the following decade in modified configurations and with new additions for different exhibitions, sometimes with new titles when reinstalled; the piece was exhibited through 1982 under its original title as well as Niagara and Niagara Extended.[146] In 1973 he also made his first pieces with printmaker William Weege at his Jones Road Print Shop and Stable in Wisconsin,[69] a relationship that would yield a sizeable body of collaborative print works, many published as editions by UW–Madison's Tandem Press, also founded by Weege.[147]

Around this time Gilliam began experimenting with assemblage, culminating with Dark as I Am, a mixed-media work that existed in the artist's studio in various forms for five years before he exhibited it as an immersive installation at Jefferson Place Gallery in November 1973.[70] The piece comprised an assemblage of tools, clothing, and found objects from his studio,[148] including his draft card from the Army,[149] all splattered with paint and attached to a wooden door hung on a wall with a ladder, paint bucket, and other objects nearby.[150] He also nailed his painting boots to a wooden board placed on the ground, hung his denim jacket on the wall next to the door,[148] scrawled crayon on the walls, and attached a pair of sunglasses to the light fixture in the small gallery.[151] Reviewing the installation after it premiered, critic Paul Richard wrote in The Washington Post[note 2] that he could "sense heaviness cut through by fun," and said he saw "anguish in [Gilliam's] playfulness."[151] In the following months Gilliam reworked elements of the assemblage, condensing them onto a smaller board and encrusting it with additional paint, renaming the new version Composed (formerly Dark as I Am). This piece and other assemblages from the period, all from his Jail Jungle series, are considered by scholars of Gilliam's work to be unique within his overall oeuvre, in that they are straightforwardly autobiographical or narrative works.[113][152][153] The title Jail Jungle was a phrase one of Gilliam's daughters thought up while walking through a run-down neighborhood on her way to school.[154] Gilliam said this series was an attempt to "shock" viewers familiar with his preexisting style,[155] and that Composed was developed as a somewhat humorous response to his sense that abstract art by black artists was not being accepted as a valid form of expression, in particular in response to a critic who wrote that Gilliam "had painted [himself] out of the race."[156] Binstock[note 1] suggested Composed represented Gilliam's "most explicit response to the accusation that he was indifferent to the challenges that faced African Americans" because he was pursuing abstraction instead of representational art.[116] Speaking several decades later on the subject of race in his art, Gilliam said:

"I do not see myself as a particularly Afro-American artist, in the sense that it is the subject of my art. I am an Afro-American artist. I am who I am in that regard. But I feel that specific questions raised about race do not relate to what I do."

— Sam Gilliam, in William R. Ferris, "Sam Gilliam". The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists (2013)[157]

After completing Composed, Gilliam began to develop collage techniques in 1974, cutting out shapes from different stained canvases and collaging them into geometric designs, often comprising a circular collage within a larger square,[158][128] marking Gilliam's first engagement with a circle motif.[159] These early collages combined the precise geometries of his hard-edge color field work with the dynamic patterns and contrasting hues from his Slice paintings and watercolors.[158][128]

Gilliam was included in the Corcoran's 34th Biennial of Contemporary American Painting in February 1975,[160] debuting Three Panels for Mr. Robeson, named for the singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson.[68][161] Two years prior, Butler, while still writing for The Washington Post,[note 2] had begun research for a biography on Robeson when their young daughter Melissa noticed her mother's excitement and wrote Robeson a letter asking him to be interviewed, inspiring Gilliam to begin his own project honoring Robeson.[162][161] Three Panels comprised three monumental indoor Drapes each suspended from the gallery's tall ceilings and spread horizontally across the ground to create pyramidal[161] or tent-like forms.[160] Art historian Josef Helfenstein has described Three Panels as "precarious textile architecture," and compared Gilliam's Drape installations of the period to "provisional shelter."[126] Forgey, reviewing the exhibition in The Washington Star,[note 3] praised the installation and said it "probably is the best painting he's ever made," and "Gilliam somehow brings all of his excesses together, and makes a room that is virtually saturated with painting."[160]

After the pre-opening reception for artists and press at the Corcoran, Gilliam was set to travel to the Memphis Academy of Art to deliver a lecture and teach a week-long workshop.[163] He reported feeling great stress after installing Three Panels and other large works around the country,[163] and his psychiatrist prescribed him Dalmane for anxiety, which he took for the first time before boarding his flight.[46] In the air he became disoriented and agitated, believing the plane was crashing and trying to access a life raft,[46] and on landing in Memphis he was arrested for assaulting a fellow passenger and interfering with the flight crew.[164][165] The incident was reported in the Star[note 3] and the Post[note 2] while the Corcoran exhibition was opening to the public.[164][165] The case went to court later that year, where a court-ordered psychiatrist testified that he had been "suffering a temporary attack of manic depression or schizophrenia," and he was acquitted after a two-day trial.[163]

Outdoor Drapes, White & Black Paintings

editIn the run-up to the Corcoran exhibition, Gilliam also prepared one of his largest and most well-known draped works, Seahorses, his first commissioned work of public art. This was exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art as part of a city-wide festival in April and May 1975.[166] Inspired by the large bronze rings that decorate the top of the museum's building, which Gilliam said had made him imagine Neptune using them to tie seahorses to his temple,[167] the work consisted of six monumental unstretched painted canvases, two measuring 40 x 95 ft each and four measuring 30 x 60 ft each,[168] all hung from their respective top corners on the outside walls of the museum, attached via the rings and drooping down in upside-down arches of folds.[169] In 1977 he reinstalled the work for a second and final time, with five canvases instead of six, on the outside of the Brooklyn Museum.[161] Seahorses was made with traditional canvas material displayed open to the elements and was blown off the museums' walls by the wind in both Philadelphia and Brooklyn,[170][15] and the canvases were tattered and partly destroyed by the time he deinstalled them in New York.[171]

In the mid-1970s Gilliam started covering stained canvases with thick layers of white acrylic paint and acrylic hardener that made them appear more dimensional than the earlier white Ahab paintings, raking the surfaces to achieve texture and physical depth. He then cut long sections from these canvases and collaged them in horizontal or vertical arrangements, disrupting the patterns on their surfaces.[158][172] This series was formalized in 1976 as his White Paintings.[172]

In 1977 Gilliam completed his first formal engagement with land art during an artist residency at the Artpark State Park in upstate New York.[173][174] His work Custom Road Slide comprised multiple different installations of stained fabrics, woods, and rocks draped across the landscape, which he re-worked and re-installed over the course of the residency.[173][174] In 1977 he was also one of the first artists-in-residence at the newly established Fabric Workshop and Museum, where he used the workshop's industrial screenprinter to add printed designs to fabric Drape works instead of paint.[175][176] Critic Grace Glueck called this work "as subtle and beautiful as his abstract paintings."[177]

In the late 70s he explored a different end of the color spectrum with his Black Paintings, which he described as a decision "to create a fork in the road" for himself after the White Paintings.[172] He adjusted his collage technique, cutting one or more shapes from paintings in progress and collaging them in a central position onto a separate, larger, brightly stained and traditionally stretched canvas.[178][179] He continued experimenting with new surface qualities and textures, using different paints, hardeners, and physical materials in a specific combination he later said he could no longer remember, producing layered black compositions on top of the collage that resembled rocky tar or asphalt and extended over the beveled edges of the rectangular canvases.[180][179] Works like Azure and Rail exemplify this series,[172] with flecks of bright color and outlines of sharp geometric shapes partly visible under a thick impasto of black paint.[158][180] His Black Paintings were widely acclaimed when he began exhibiting them and brought a new wave of institutional support.[172]

Gilliam's new critical successes led to rising prices for his work, allowing him to purchase a building near 14th and U St NW in 1979[note 4] that he shared with Krebs and which served as his primary studio for over 30 years,[181] in exchange for $60,000 and three of his paintings.[52]

1980s-1990s

editChasers, wood and metal constructions

editIterating on what he explored in the textures of his Black Paintings, by 1980 Gilliam had begun to further build up the surfaces of the canvases with additional collaged pieces and colors beyond black and white.[182] He also experimented with stretching the stained and collaged canvases over irregular polygonal beveled stretchers each with nine distinct edges, before covering them with raked fields of paint,[183] producing seventeen of these new forms that he called Chasers.[182] This marked a return to the exploration of painting as sculpture, with art historian Steven Zucker describing one of the Chasers as "an object on the wall, not so much a painting we're looking into."[184] The combination of colors, textures, and shapes have led multiple critics and historians to describe the Chaser paintings and others from the period as "quilted," for their resemblance to African and African-American quilting patterns.[184][185] The transition between his Black Paintings and Chasers can be seen most clearly in his Wild Goose Chase series.[9][note 5]

He adjusted his approach to shaped canvases with his Red and Black series, produced by constructing multiple sharply angular geometric canvases all attached in a row, many of which can be displayed in multiple arrangements or installed around corners.[115][187] Alternately painted in all black or all red acrylic paint mixed with Rhoplex - an acrylic emulsion - and extensively raked on their surfaces, the paintings featured similar textures to his previous series, but with the addition of distinct lines dragged through the paint to create the outlines of geometric forms imposed on top of and within the compositions.[115][182] Gilliam presented a set of Red and Black paintings at a solo exhibition at the Studio Museum in 1982 along with several of his "D" paintings, created during the same period, each of which comprise small stretched canvases built up with pigment and collage, usually adorned with a singular painted metal element - the letter D - on a corner of the painting, partly extending off the edge of the work.[115] Gilliam and Butler separated in 1982, divorcing soon after.[181]

Gilliam's "D" paintings began with the development of his large-scale public commission Sculpture with a "D",[188] which he said was "an example of direct conversion of the ideas behind the draped paintings into a more formal material: metal," and he called his works from this period "constructed painting."[189] In the mid-late 1980s he extensively integrated painted and printed metals, wood and plastics as the primary material in many new works, creating multidimensional collages with alternating patterns, textures, shapes, and materials.[190][191] Gilliam hired a second studio assistant around 1985 to help him complete these increasingly heavy and labor-intensive works, and by the 1990s his sculptured paintings had become more elaborate, taking the form of both free-standing sculptures and wall-based constructions.[192] He also started using new elements like piano and door hinges to create visual layers in different sections of the compositions, giving the works hinged panels that can be displayed folded in or out.[191]

Art world decline, continued commissions

editIn the late 1980s through the early 2000s, Gilliam was somewhat overlooked by the New York art world;[11][7] he showed his work very infrequently in New York,[7] but he continued to produce paintings and sculptures in new forms and developed new approaches to abstraction, exhibiting extensively in Washington, across the country, and in several international exhibitions.[11] Speaking about staying in Washington, Gilliam himself said in 1989 that "I’ve learned the difference between what is really good and real for me and what is something that I dreamed would be real and good for me. I’ve learned to — I don’t mean to say I’ve learned to love this — but I’ve learned to accept this, the matter of staying here."[7] Binstock argued that Gilliam's choices to pursue abstraction as a black artist and to not have a permanent gallery contributed to what he deemed "a process of growth or expansion and then perhaps a cooling or retrenching period."[8] Speaking in 2013, Gilliam offered another explanation as to why he may have been overlooked by some in the art world, suggesting that younger post-black artists making work during this era had been "able to do something I was not – to keep the political in the front," and that they had received greater attention for it.[6] This term, usually attributed to curator Thelma Golden, is meant to describe black artists who explicitly invoke and explore black history, culture, and politics in their work but refuse the label of "black art" to avoid singular ideas of how all black people or culture should be represented and the responsibilities associated with that representation.[193][194]

Additionally, several authors - and Gilliam's family[48] - rebutted the idea that his career truly declined, given the breadth of exhibitions he staged and participated in during the period, and suggested in retrospect that this was an overdramatized narrative.[195][48] Greg Allen, writing in Art in America, said "if, at some periods in his extensive career, Gilliam seemed invisible, it’s simply because people refused to see him."[195] Contemporaneous reviews of Gilliam's work in Washington, and elsewhere during this period were positive and framed his career as an ongoing success.[196] Critic Alice Thorson described Gilliam in the Washington City Paper in 1991 as "an acknowledged master of 20th-century painting and Washington's most famous living artist;"[197] and the Associated Press described him in 1996 as "one of the few black American artists welcomed into the mainstream."[198]

Throughout the 1990s Gilliam completed a number of public and private commissions in relatively quick succession, received several grants, and regularly sold his work,[48] with consistent acquisitions at museums and galleries at HBCUs in particular.[199] His commissions during this period mostly comprised larger painted sculptures like Dihedral, a monumental painted aluminum work made of helix-like forms hung from the ceiling via aircraft cables and stretching across multiple floors in an atrium in the former Terminal B at LaGuardia Airport in 1996,[200][201] and The Real Blue, a multi-part painted wood construction placed on four separate ledges near the ceiling in the University of Michigan School of Social Work's library in 1998.[202]

Gilliam collaborated with Weege in 1991 on a large Drape work decorated with woodcut engravings at the Walker Hill Art Center in Seoul,[203][204] one of a large number of international presentations of his work, many coordinated by the State Department.[17] Gilliam was invited in 1997 to create an installation at the Kunstmuseum Kloster Unser Lieben Frauen in Magdeburg, Germany, inside the museum's historic chapel.[205] He re-used the printed fabric he made with Weege, adding paint to the work before sewing it in strips from the chapel ceiling.[202]

Gilliam was the first artist to stage a solo exhibition at Washington's Kreeger Museum, in 1998.[11] He presented work experimenting with new forms of site-specificity, including paintings on wood with digitally rendered details of the Kreeger's noted Modernist architecture,[206] and a temporary installation of small Drape paintings that Gilliam floated in the museum's outdoor swimming pool.[11]

2000s–2020s

editSlatts, retrospective

editBeginning in the early 2000s, Gilliam returned to a new version of his early-career geometric abstractions;[207] after experimenting with making monochromatic print works in 2001 at Ohio University, he developed a series of monochrome paintings on wood that he first called Slats and later renamed Slatts.[208] He built up thick surfaces of high-gloss acrylic with gel medium on wood to create wall-based works with polished, nearly reflective surfaces,[209] some with puzzle-like insets of alternating rectangles.[210][191]

Gilliam staged his first full retrospective in 2005 at the Corcoran, curated by Binstock, who also wrote Gilliam's first monograph to accompany the exhibition.[211] Binstock, who first met Gilliam in the 1990s in research for his dissertation on Gilliam's career, has said that he was hired by the Corcoran on the specific condition that he begin planning the retrospective.[11] In reviewing the exhibition for The Washington Post, critic Michael O'Sullivan identified a broad stylistic range in Gilliam's career and said he "can be seen moving forward and backward stylistically, dropping one thing, only to pick it up again years later."[210]

Gilliam sold his studio at 14th and U St NW - in a neighborhood that had experienced intense gentrification since he bought the property in 1979 - for $3.85 million in 2010, moving to a new building in the Sixteenth Street Heights neighborhood.[52]

In conjunction with The Phillips Collection's 90th anniversary in 2011, Gilliam was commissioned to create a site-specific installation for the large well next to the museum's interior elliptical spiral staircase, nearly 45 years after his debut solo museum show, at The Phillips in 1967.[212][83] Later that year he staged a solo exhibition at the American University Museum, creating another site-specific Drape work.[195][213] Elaborating on his approach to creating site-specific installations, he explained to the curator that in his view, "You don't remove the artwork from its environment, so that the painting is not the painting, it can be the wind."[214]

Health challenges, resurgence, and late-career acclaim

editFor several years in the early 2010s, Gilliam dealt with severe health complications from his long-term use of lithium to treat his bipolar disorder, which had extensively damaged his kidneys and brought on several years of depression.[47][48] He was mostly unable to work and his daughter Melissa described him during this time as "sort of catatonic on the couch."[48]

Gilliam staged an exhibition of his early hard-edge abstract paintings in 2013 at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, curated by the younger artist Rashid Johnson, which brought a new wave of national media attention to his work.[52] David Kordansky had bonded with Johnson - a noted conceptual artist,[215] whose work during this period was often described as post-black[216] - over their mutual admiration of Gilliam's early paintings and they approached him together in 2012 to offer gallery representation and propose an exhibition, an offer that, according to Kordansky, moved Gilliam to tears.[217][218] Speaking about Johnson at the time of the exhibition, Gilliam said "He's more of a documentary-type artist [...] I'm a picture artist; he's conceptual."[215] Critic Kriston Capps, writing in the Washington City Paper, argued this "rediscovery" of Gilliam's work by critics and the market had actually occurred several times over the course of his career, and suggested that Gilliam was emotional at Kordansky and Johnson's offer because they were "promising the one thing that has always eluded him. No, not success [...] but context."[52] Gilliam himself later said that Kordansky "has been the best thing for me," because "he’s an artist himself and he works for you;"[219] Kordansky subsequently helped place works by the artist in the Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art and organized several exhibitions of Gilliam's historical and new work.[52]

Several news outlets reporting on Gilliam's resurgence embellished the degree to which his career had suffered in previous decades or incorrectly described him as having disappeared completely:[48][52] The New York Times was forced to run a correction after claiming that Gilliam had once bartered his paintings in exchange for laundry detergent,[52] and The Guardian claimed Kordansky and Johnson had "saved [him] from oblivion."[218][48]

After switching doctors and stopping the use of lithium around 2014,[47] Gilliam saw significant recovery from his health challenges and began to create work and travel at a much more rapid pace.[48]

Throughout the next decade Gilliam participated in a large number of high-profile solo and group shows and created several new commissions,[7] including a permanent installation in the lobby of the newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, in 2016.[220] His painting, Yet Do I Marvel, Countee Cullen, comprises a series of glossy geometric colored rectangles of acrylic on wood in the style he began exploring in the mid-2000s, and was inspired by the Harlem Renaissance writer Countee Cullen's poem which serves as the work's title.[221] The following year he exhibited at the Venice Biennale for a second time, in the Giardini's main pavilion for the show Viva Arte Viva.[7] His work Yves Klein Blue, a large-scale Drape painting, was hung outside the entrance of the venue, similar to his early commission Seahorses from the 1970s, and Gilliam said that he wanted the piece "to billow like that early work."[25][222] His first solo museum exhibition in Europe, Sam Gilliam: Music of Color, was hosted in 2018 by the Kunstmuseum Basel, focusing primarily on his early Drape and Slice paintings.[223][224] The same year he staged a site-specific Drape installation at the art fair Art Basel.[224] Gilliam himself said that "rising prices" during this period gave him more freedom to pursue new, large works.[224] He also married Gawlak, his longtime partner, in 2018.[10]

He began to show his work more frequently in New York, staging his first solo exhibition in the city in nearly 20 years, an exhibition of historical works at Mnuchin Gallery, in 2017.[7] He then exhibited a series of new watercolor paintings at the FLAG Art Foundation in 2019.[83] The same year, Gilliam acquired representation through Pace Gallery, his first ever long-term relationship with a gallery in the city.[225] In 2020 he staged his first solo show with Pace,[226] premiering a new body of stained and painted monochrome wooden sculptures, some in the form of small pyramids on casters that can be displayed in different combinations, which had been inspired by his time in Basel, where he said he saw many recently arrived migrants, leading him to think more deeply about the shapes of what he called "early Africa."[144]

Gilliam was originally scheduled to present a full-career retrospective at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, in 2020, but the exhibition was delayed and reworked due to the pandemic.[227] The show eventually opened in May 2022 as an exhibition of chiefly new work;[1] he debuted a series of tondo paintings, the first of Gilliam's works in that form, comprising circular compositions on wood board in beveled frames containing fields of pockmarked paint textured with wood shavings, small metal ball bearings, and detritus from his studio, with the compositions sometimes overflowing onto the frames themselves.[228][229] The paintings' beveled frames and exploration of the circle represented a return to forms the artist had originally explored in the 1960s and 1970s.[159] Speaking in the run-up to the show, Gilliam called it "a real beautiful ending;"[230] the exhibition opened one month before Gilliam's death and was his final show during his lifetime.[231]

Personal life

editIn 1962, Gilliam married Dorothy Butler, a Louisville native and the first African-American female columnist at The Washington Post. They had three children together: Stephanie (b. 1963),[32] Melissa (b. 1965),[32] and L. Franklin (b. 1967).[69] Gilliam and Butler separated in 1982 and divorced soon after.[181] In 1986 he met Annie Gawlak, the owner of Washington's G Fine Art gallery.[232] Gilliam and Gawlak married in 2018 after a 30-year partnership.[52]

Gilliam died of renal failure at his home in D.C., on June 25, 2022, at the age of 88.[7]

Selected permanent public artwork

editStarting in the late 1970s, some of Gilliam's works were commissions for public buildings. His first work made for permanent public display was Triple Variants, an unstretched canvas in earthy tones with extensive cut-outs, bolted flat and draped against the wall, with two curved blocks of marble and an aluminum beam resting on the ground.[188] It was commissioned through the Art in Architecture Program of the General Services Administration,[233] and installed in the Richard B. Russell Federal Building in Atlanta in 1979.[234][235]

Some of his works are installed in university buildings. In 1986, Solar Canopy was installed in a lounge in York College. It is a 34'x 12' sculpture of painted 3D aluminum shapes, suspended from a 60 ft (18 m) ceiling, with a central annulus supporting other shapes below it.[236] And in 2002, Philander Smith College in Arkansas commissioned Chair Key, a draped canvas, for their library.[237]

Other installations were commissions for transit stations and airports.[238] In 1980 he designed Sculpture with a D under an Arts on the Line commission. It was installed in 1983 for the Davis subway station on Boston's Red Line. This collection of overlapping aluminum shapes was painted with a mix of primary colors and tie-dye paint, attached to one another and to a supporting grid. Looked at from different angles, letters in the collection spell out the name of the station.[239] In 1991, his geometric aluminum sculpture, Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue was installed in the Jamaica Center station,[240] over a staircase. The sculpture has a blue outer ellipse with red and yellow inner parts, representing the subway lines. In the artist's words, the predominant blue offers "a visual solid in a transitional area that is near subterranean," and the work calls to mind "movement, circuits, speed, technology, and passenger ships".[241] And in 2011, his glass mosaic From Model to Rainbow was installed in an open-air passageway in Takoma station on the Washington Metro.[242]

Gilliam's final permanent public commission - A Lovely Blue and ! - is a 20 × 8 ft painting on a beveled stretcher completed in 2021, created for the lobby of the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center in the former Newseum building in Washington,[243] and installed in 2023.[244]

Awards and grants

editGilliam's work was broadly acclaimed during his lifetime and he received numerous awards and grants.

He received eight honorary doctorates,[52] including from his alma mater the University of Louisville, in 1980, and he was named the 2006 alumnus of the year.[245] He was awarded the Art Institute of Chicago's Norman Walt Harris Prize,[246] the Kentucky Governor's Award in the Arts,[245] and the State Department's inaugural Medal of Art Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015 for his longtime contributions to the Art in Embassies Program;[52][17] his work was shown in embassies and diplomatic facilities in over 20 countries during his career.[52] He received multiple NEA grants starting in 1967, and he participated in numerous fellowships and artist-in-residence programs, including at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art in 1968 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1971.[247]

Exhibitions

editGilliam regularly staged exhibitions in the United States and internationally. Notable group exhibitions included The De Luxe Show (1971) in Houston;[248] the Venice Biennale in 1972[8] and 2017;[25] and the Marrakech Biennale in 2016.[249] He also staged a series of three-artist shows with Mel Edwards and William T. Williams titled Interconnections (1972) at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; Extensions (1974) at the Wadsworth Atheneum; Resonance (1976) at Morgan State University;[250] and Epistrophy (2021) at Pace Gallery.[251]

His final exhibition during his lifetime, Sam Gilliam: Full Circle, opened in May 2022 at Washington's Hirshhorn Museum, one month before his death.[1]

Notable solo exhibitions

edit- Paintings by Sam Gilliam (1967), The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.[252]

- Projects: Sam Gilliam (1971), Museum of Modern Art, New York[253]

- Red & Black to “D”: Paintings by Sam Gilliam (1982–1983), Studio Museum in Harlem, New York[254]

- Sam Gilliam: Construction (1996), Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky[255]

- Sam Gilliam: A Retrospective (2005–2007), originating at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[256]

- Sam Gilliam: Hard Edge Paintings 1963-1966 (2013), David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

- Sam Gilliam: The Music of Color (2018), Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland[257]

- Existed Existing (2020), Pace Gallery, New York[258]

- Sam Gilliam: Full Circle (2022), Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C.[227]

Posthumous exhibitions

editFollowing his death, several galleries and museums staged posthumous exhibitions of his work, including: Late Paintings, which opened at Pace's London gallery in 2022;[259] RECOLLECT: Sam Gilliam, which opened at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art in 2023;[260] and The Last Five Years, a two-part exhibition staged at Pace's New York gallery in 2023 and Kordansky in Los Angeles in 2024.[261]

Notable works in public collections

edit- Shoot Six (1965), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[262]

- Red Petals (1967), The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.[263]

- April 4 (1969) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.[264]

- Rondo (1971), Kunstmuseum Basel[265]

- "A" and the Carpenter I (1973), Art Institute of Chicago[266]

- Rail (1977), Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.[267]

- Master Builder Pieces and Eagles (1981), Studio Museum in Harlem, New York[268]

- Yet Do I Marvel (Countee Cullen) (2016), National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.[269]

Art market

editGilliam exhibited and sold his work through a broad array of galleries in Washington, throughout the United States, and internationally, and his career was marked by multiple periods of both rising and stagnating interest in - and prices for - his work.[52] Gilliam's painting Lady Day II sold at auction in November 2018 at Christie's in New York for $2.17 million, a record for the artist.[107][270]

Gilliam's first exclusive dealer in Washington was Jefferson Place Gallery from 1965 to 1973,[15] followed by Fendrick Gallery, and then Middendorf/Lane Gallery.[69] He was represented in Paris by gallerist Darthea Speyer from 1970 until she closed her practice in the 2000s,[52] Gilliam's longest continuous relationship with any gallery.[69] Between the 1970s and early 2010s he had relationships with dealers in cities across the country.[250] In the late 1990s he began to show extensively with Marsha Mateyka Gallery in D.C.,[232] his primary dealer until he joined David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles in 2013,[52] and Pace Gallery in 2019 - his first-ever exclusive New York dealer - which both co-represented the artist until his death.[7] Kordansky and Pace continue to co-represent Gilliam's estate.

Citations and notes

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f Jonathan P. Binstock, curator, art historian, and director of The Phillips Collection, is the most widely cited scholar on Gilliam's life and career, having first begun a correspondence with the artist in the 1990s in research for his Ph.D. dissertation on Gilliam's art.[27] As the most broadly published author of both early histories of Gilliam's life and later evolutions in his career and style, as well as the curator of two of Gilliam's career retrospective exhibitions, Binstock is extensively cited throughout this article.

- ^ a b c d e f This publication, referred to here as The Washington Post for consistency, was published during Gilliam's life as both The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973) and The Washington Post (1973-).

- ^ a b c d This publication, referred to here as The Washington Star for consistency, was published between 1966 and its final printing in 1981 variously as The Evening Star (through 1972); The Sunday Star (Sundays through 1972); The Evening Star and Washington Daily News (1972-1973); The Washington Star-News (1973-1975); The Washington Star and Daily News (1975); and The Washington Star (1975-1981).

- ^ Interviewed in 2015, Gilliam's second wife Annie Gawlak said his U St studio was purchased "in the early 1970s;"[52] Binstock and Helfenstein, writing in 2018 in a revised chronology of Gilliam's career, cited 1979 as the year of purchase.[181]

- ^ Wild Goose Chase and Chevrons are both names of common quilt patterns.[186]

Citations

edit- ^ a b c d e f g O'Sullivan, Michael (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, abstract artist who went beyond the frame, dies at 88". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. LCCN sn79002172. OCLC 2269358. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ Panero, James (August 19, 2020). "'Sam Gilliam' Review: Flowing Color, Billowing Canvas". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 27, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Cohen, Jean Lawlor (June 26, 2015). "When the Washington Color School earned its stripes on the national stage". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. LCCN sn79002172. OCLC 2269358. Archived from the original on August 2, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Smee, Sebastian (June 28, 2022). "Sam Gilliam never fought the canvas. He liberated it". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. LCCN sn79002172. OCLC 2269358. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ Di Liscia, Valentina (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, Groundbreaking Abstractionist, Dies at 88". Hyperallergic. OCLC 881810209. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Rappolt, Mark (July 21, 2014). "Feature: Sam Gilliam". ArtReview. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Smith, Roberta (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, Abstract Artist of Drape Paintings, Dies at 88". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. LCCN sn78004456. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Kinsella, Eileen (January 2, 2018). "At Age 84, Living Legend Sam Gilliam Is Enjoying His Greatest Renaissance Yet". Artnet News. Archived from the original on November 27, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Sam Gilliam". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on December 9, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ a b Basciano, Oliver (June 30, 2022). "Sam Gilliam obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 14, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Capps, Kriston (July 8, 2022). "Painter Sam Gilliam Spent His Entire Career in Washington, D.C. Here's How the City Sustained Him When the Art World Wasn't Watching". Artnet News. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Sam Gilliam Biography". Ogden Museum of Southern Art. April 8, 2020. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c Binstock (2005), p. 7

- ^ Obrist (2020), p. 37

- ^ a b c d Samet, Jennifer (March 19, 2016). "Beer with a Painter: Sam Gilliam". Hyperallergic. OCLC 881810209. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Ferris (2013), p. 202

- ^ a b c "Sam Gilliam | Medal of Arts 2015". Art in Embassies. United States Department of State. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ a b c Brown (2017), p. 62

- ^ Binstock & Webb (2005), p. 157

- ^ Binstock (2005), pp. 8–9

- ^ a b c d Raynor, Vivien (February 17, 1974). "The Art of Survival (and Vice Versa): Four Young Artists Illustrate the Shift from Bohemia to Bureaucracy". The New York Times Magazine. p. 304. ISSN 0028-7822. OCLC 45309770.

- ^ Obrist (2020), p. 41: "I did that in college. If you paint on paper, particularly on a hard surface paper, it pushes back. It holds the color up. The water moves, or it moves with the paper so you can't stop it. You go with the flow, and you don't have to play just for the accidental aspect. You can learn to do deliberate things; you establish your references on the page."

- ^ a b c Binstock (2005), p. 12

- ^ a b c d e f g Binstock & Webb (2005), p. 158

- ^ a b c d e Campbell, Andrianna (July 11, 2017). "Interview: Sam Gilliam". Artforum. Archived from the original on February 1, 2024. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Triplett, Jo Anne (June 20, 2006). "Man of Constant Color: Sam Gilliam's Abstract Art Comes Home for a Retrospective". LEO Weekly. Euclid Media Group. Archived from the original on June 4, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip (November 30, 2022). "Phillips Collection Hires Art Historian as New Director". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. LCCN sn79002172. OCLC 2269358. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Binstock (2005), p. 8

- ^ Edwards (2017), p. 7

- ^ a b c Binstock (2005), p. 9

- ^ "Kenneth Victor Young: Exploring Space". East City Art. March 11, 2021. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Binstock & Helfenstein (2018), p. 182

- ^ a b c Kloner (1978), p. 15

- ^ a b c d Binstock (2005), p. 10

- ^ a b c Gilliam, Sam (November 11, 1989). "Oral history interview with Sam Gilliam". Archives of American Art Oral History Program (Interview). Interviewed by Benjamin Forgey. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Binstock & Webb (2005), p. 159