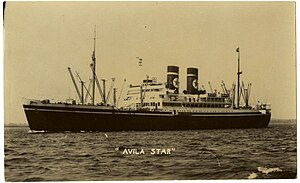

SS Avila Star, originally SS Avila, was a British turbine steamship of the Blue Star Line. She was both an ocean liner and a refrigerated cargo ship, providing a passenger service between London and South America and carrying refrigerated beef from South America to London. She was built in 1927, renamed Avila Star in 1929 and lengthened in 1935. She was sunk by a German submarine in 1942 with the loss of 84 lives.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Avila (1927–29) Avila Star (1929–42) |

| Namesake | Ávila, Spain |

| Owner | Blue Star Line |

| Operator | Blue Star Line |

| Port of registry | |

| Route | London – Rio de Janeiro – Buenos Aires |

| Ordered | 1925 |

| Builder | John Brown & Company, Clydebank |

| Yard number | 514 |

| Launched | 22 September 1926 |

| Completed | March 1927 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Torpedoed and sunk by U-201, 5 July 1942 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | passenger and refrigerated cargo liner |

| Tonnage |

|

| Length |

|

| Beam | 68.2 ft (20.8 m) |

| Draught |

|

| Depth |

|

| Decks | 3 |

| Installed power | as built: 2,007 NHP after lengthening: 1,840 NHP |

| Propulsion | as built: 5 boilers feeding 4 steam turbines driving 2 screw propellers after rebuild: boilers reduced from 5 to 4 |

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h) |

| Capacity | 162 1st class passengers plus refrigerated cargo |

| Crew | 159 plus (in wartime) 6 DEMS gunners |

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Armament | (as DEMS) |

| Notes | sister ship: Avelona Star |

Building

editIn 1925 Blue Star ordered a set of new liners for its new London – Rio de Janeiro – Buenos Aires route. Cammell Laird of Birkenhead built three sister ships: Almeda, Andalucia and Arandora. John Brown & Company of Clydebank built two: Avelona and Avila. Together the quintet came to be called the "luxury five".[1]

John Brown & Co launched Avila on 22 September 1926 and completed her in March 1927.[1] Her sister ship, Avelona, quickly followed, being launched on 6 December 1926 and completed in May 1927.[2] As originally built, Avila was 512.2 ft (156.1 m) long, had a beam of 68.2 ft (20.8 m) and a draught of 37 ft 4 in (11.38 m). She had 32 oil-fired corrugated furnaces with a combined grate area of 573 square feet (53.2 m2) heating three double-ended and two single-ended boilers with a combined heating surface of 30,580 square feet (2,841 m2). Her boilers supplied steam at a pressure of 200 psi (1,400 kPa) to four Parsons steam turbines with a combined rating of 2,007 NHP or 13,880 shaft horsepower (10,350 kW).[1] Her turbines were single-reduction geared onto the shafts to drive her twin screws at about 120 RPM,[1] giving her a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h).[3][4] Avila was fitted with wireless direction finding equipment.[5]

Avila was painted in Blue Star Line's standard livery of the era. Her hull was black, her boot-topping red and her masts white. Her stokehold ventilators were black and her deck ventilators were white, and the insides of her ventilator cowls were red.[6] She had two funnels and they were red with a black top, with a narrow white and a narrow black band and on each side a large blue star on a white disc.[3] In her original form Avila's funnels had a type of cowl called an "Admiralty top".

Early service

editAvila made her maiden voyage in April 1927 on Blue Star Line's route between London and Buenos Aires via Boulogne, Madeira, Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro, Santos and Montevideo. In 1929 Blue Star added "Star" to the end of the name of each of its ships. This may have been partly to help distinguish Blue Star from Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, whose ships bore similar Spanish names. RMSP was an old company with a distinguished history, but had got into difficulties and collapsed amid financial scandal in 1932.[citation needed]

Rebuilding

editIn 1935 Blue Star had Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company of Jarrow lengthen Avila Star and Avelona Star from 510.2 feet (155.5 m) to 550.4 feet (167.8 m).[7] Palmers replaced Almeda Star's bow with a Maierform one. This design pioneered by Austrian shipbuilding engineer Fritz Maier and developed by his son Erich Maier, had a convex profile that was intended to increase hydrodynamic efficiency.[8]

Steaming arrangements were reduced to 28 corrugated furnaces with a combined grate area of 490 square feet (46 m2) heating three double-ended boilers and one single-ended boiler with a combined heating surface of 26,758 square feet (2,485.9 m2). The combined rating of Almeda Star's turbines was reduced to 1,840 NHP. An echo sounding device was added to Avila Star's navigation equipment.[7] A change more visible externally was that the Admiralty tops were removed from her two funnels.

Palmers' alterations increased Almeda Star's draught from 37 ft 4 in (11.38 m) to 46 ft 0 in (14.02 m), and her tonnages from 12,872 GRT and 7,878 NRT to 14,443 GRT and 8,836 NRT.[7]

Wartime service

editAfter the UK entered the Second World War Avila Star became a Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships. She continued her valuable service shipping frozen meat from South America to Britain but was largely left to sail unescorted. At first she continued her peacetime route of London – Lisbon – Mindelo, Cape Verde – Rio de Janeiro – Santos – Montevideo – Buenos Aires. After May 1940 she stopped using the Port of London and no longer called at Lisbon. In June France surrendered to Germany and in July–August 1940 Avila Star docked in Cardiff and Swansea to avoid a now-dangerous voyage via the English Channel and North Sea to London. There were repeated Luftwaffe attacks on Cardiff, and on her next two arrivals home in September 1940 and January 1941 Avila Star docked in Liverpool. In October 1940 Avila Star took part in her first convoy, OL 9, which left Liverpool on 25 October and dispersed in the Atlantic two days later.[9] In November she called at Rio de Janeiro and Santos on her outward voyage but not on her return from Buenos Aires and Montevideo.[10]

The Luftwaffe was also inflicting heavy damage on Liverpool and April 1941 Avila Star changed again, calling at Belfast Lough and docking at Avonmouth.[10] Avila Star's route was changed again, now omitting Mindelo as well as Lisbon. This trip was also her last visit to Rio de Janeiro, where she called on her outward trip on 12 May but not on her return trip or any subsequent voyage.[10]

Returning from South America she now called at Trinidad on 10 June 1941. After May 1941 Luftwaffe raids on Liverpool reduced, so on 26 June she docked in Liverpool. On this visit she also called at Avonmouth and Belfast Lough, and then on 8 July 1941 reached the Firth of Clyde to join Convoy WS 9C. This heavily escorted fleet left on 12 July and went as far as Gibraltar.[11] Thence Avila Star continued via Trinidad and straight on to Buenos Aires. On her return voyage she called at Trinidad again on 23–27 June 1941, Belfast Lough on 1 October and reached Avonmouth on 2 October.[10]

Avila Star's route was now changed yet again. She left Avonmouth on 15 October 1941 and reached the Firth of Clyde the next day. This time she joined a small transatlantic convoy, CT 4, which seems to have been three passenger liners sailing together with no naval escort.[12] CT 4 left the Clyde on 17 October bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, but Avila seems to have left en route to reach Trinidad on 30 October without calling at Halifax. She then called at Buenos Aires and Montevideo and returned via Trinidad to reach Liverpool on 26 December 1941.[10]

In 1942 Avila Star had more changes of route. After leaving Liverpool on 14 January she called at Bermuda on the 25th before reaching Trinidad on the 31st. After her usual calls at Buenos Aires and Montevideo she returned via Freetown, Sierra Leone. If she was seeking a home-bound convoy she found none, for she sailed unescorted two days later and reached Liverpool on 28 March.[10]

Loss

editAvila Star's next outward voyage she left Liverpool on 20 April, went straight to Trinidad and reached Buenos Aires on 16 May. She loaded a cargo of 5,659 tons of frozen meat and embarked passengers, left Buenos Aires on 12 June, called at Montevideo three days later, and then set off across the South Atlantic for Freetown. One passenger, Maria Elizabeth ″Mary″ Ferguson (20 June 1923 – 16 June 2006), was a young British woman from Argentina on her way to enlist in the WRNS. On 20 June, five days out of Montevideo, she celebrated her 19th birthday aboard.[13]

In mid-Atlantic Avila Star found and rescued the First and Third officers and a DEMS gunner from J&J Denholm's 5,186 GRT cargo steamship Lylepark, which the German auxiliary cruiser Michel had sunk in on 11 June.[14] Avila Star reached Freetown on 28 June.[10] Again she seems not to have found a suitable home-bound convoy, as she left unescorted. On this leg of her voyage the liner was carrying 30 passengers, including 10 women and the three survivors from Lylepark that she had rescued. Her Master was Captain John Fisher. The crew and passengers had a lifeboat drill every day, and throughout the voyage each person either wore or carried a lifejacket plus a red marker light to attach to it.[1]

On the evening of 5 July the German submarine U-201 (Oblt. Adalbert Schnee) started following Avila. At 00:36 on 6 July by Berlin Time, 90 miles (140 km) east of São Miguel in the Azores, the submarine hit Avila's starboard side with two G7e torpedoes,[15] one of which detonated in her boiler room.[1]

The order was given to abandon ship. The ship's engines and main generator were disabled, but her emergency dynamo was started which restored electric light. Avila Star carried eight lifeboats: the odd-numbered ones on her starboard side and the even-numbered ones on her port side. Crew and passengers proceeded calmly but there was an accident with No. 5 boat, the after fall of which descended far too quickly. The boat was left suspended by the bow, tipping some of its occupants and most of its equipment into the sea below.[1]

At 0054 U-201 attempted a coup de grâce with a third torpedo but it failed to detonate. At 0058 the submarine fired a fourth torpedo, which struck the liner amidships.[15] The torpedo exploded beneath No. 7 boat, which had just been lowered with a full complement of passengers and crew. The Second Officer, John Anson, blames this incident for most of Avila Star's casualties. The bottom was blown out of the boat, but its buoyancy tanks kept it afloat.[1]

One of No. 7 boat's occupants was the ship's doctor, Maynard Crawford. He was thrown in the air and fell in the sea in a layer of oil far from both the ship and the boat. Dr Crawford was wearing a rucksack packed with medicines, dressings and a syringe to treat survivors, but alone in the water he had to abandon it to swim for his life. He was eventually rescued by No. 4 boat, commanded by the Chief Officer, Eric Pearce.[1]

Another of No. 7's occupants was Mary Ferguson. She was thrown 15 feet (5 m) in the air, hitting her head on a block that momentarily knocked her unconscious. She swallowed oily water but regained consciousness in the sea and swam back to the remains of No. 7 boat. She shared the stern of the damaged boat with four wounded men whom she nursed through the night.[13]

After all boats had been launched four crew remained aboard ship: Captain Fisher, his First Officer, Michael Tallack, the junior Fourth Engineer, Habid Massouda, and a quartermaster, John Campbell. They jumped overboard with lifebuoys and oars for buoyancy. Campbell was lost without trace. Massouda and Captain Fisher survived the jump but later died in the cold sea. No. 4 boat eventually rescued Tallack.[1] Avila Star sank about 01:10. One report says she capsized to starboard;[15] another that she sank fo'c's'le first.[1]

In the lifeboats

editAt daybreak on 6 July the boats found each other. No. 8 was flooded but had been bailed out, and had an engine that could now be started. Tallack was transferred from No. 4 to No. 8 boat to take charge of her. No. 8 then rescued the men from the waterlogged remains of No. 7 boat.[1] The last to leave, however, swam to No. 2 boat.[13] No. 5 boat was leaking badly and had to be abandoned. The boatswain commanded No. 1 boat. Second Officer Anson commanded No. 2 boat, whose occupants included Ferguson and four other passengers. The Chief Officer from Lylepark, Robert Reid, commanded No. 6.[1]

Boats 1, 4 and 8

editThe nearest land was the Azores 90 miles (140 km) to the west, but with crude navigation in lifeboats there was too great a risk of missing the islands and continuing out into the Atlantic. Therefore, the boats sailed east together, aiming for mainland Portugal 600 miles (1,000 km) to the east. At nightfall the boats' commanders disagreed as to what to do. Tallack wanted all boats to lower sail and heave to with their sea anchors to allow survivors to rest. Anson and Reid with boats 2 and 6 chose to continue east, leaving boats 1 and 4 with the motor boat No. 8. On 7 July boats 1, 4 and 8 again began to east together, but Tallack soon became concerned for the condition of his wounded survivors. After consultation he and No. 8 boat therefore left boats 1 and 4 together and sailed east as quickly as possible.[1]

At nightfall Tallack switched from sail to motor power and continued east. At about 21:30 he sighted the lights of a neutral ship on No. 8 boat's port beam. He altered course to port toward the ship and signalled to it with distress flares. The ship was a Portuguese Navy Douro-class destroyer, NRP Lima, en route from Lisbon to Ponta Delgada on São Miguel Island in the Azores. She rescued the occupants of No. 8 boat and then proceeded west, where she found and rescued the occupants of Nos. 1 and 4 boats. The Lima then spent more than 24 hours searching for Nos. 2 and 6 boats, but then ran short of fuel and had to continue to Ponta Delgada.[1]

Boats 2 and 6

editBoats 2 and 6 kept together until 11 July, sailing by day and heaving to with their sea anchors by night. On 8 July one man was transferred from No. 2 to No. 6. On 11 July the two boats estimated they were 370 miles (600 km) from the Portuguese coast. That evening No. 6 was unable to deploy her sea anchor and the two boats lost contact. Mr Reid and the 23 occupants of No. 6 boat were never seen again.[1]

No. 2 boat had 40 occupants. Half were covered with oil, one had a smashed and bleeding hand and injured ankle, a second had a bad cut across his eyebrow and a third seemed to have a broken rib.[1] Five were passengers, including two women, Mary Ferguson and Pat Traunter. Food and water rations were short, but Ferguson and Traunter firmly refused all offers of preferential treatment.[13]

On the night of 11 July one man grew delirious. His companions kept watch on him but at 04:10 on 13 July he jumped overboard saying he was going for a swim. Anson brought the boat round and the crew rowed against the heavy sea for 50 minutes, but they failed to find him. On 14 July the man with the wounded hand and foot was feared to have gangrene in his foot. Another crewman was reported to have drunk seawater. Anson feared that a north northeast wind was putting the boat off course, making it impossible to reach Portugal. He estimated the coast of Spain to be 225 miles (360 km) away.[1]

On 16 July one passenger was very weak with dysentery and others of the crew could no longer chew their rations. The boat was very short of food and water. On 17 July Anson estimated the coast to be 4 miles (6 km) away, but he had overestimated the boat's progress and they were still far from land. On 20 July the passenger with dysentery died and his body was committed to the sea. On 22 July another male passenger died and his body was also committed to the sea.[1] Anson was now too weak to remain in command and handed over to the Third Officer, Richard Clarke.[16]

On 23 July at 10:30 two Portuguese Naval Aviation aeroplanes sighted and circled the boat. The Third Officer, William Clarke, described them as "seaplanes" but they may have been Grumman G-21 Goose flying boats. The planes dropped three lifejackets with bottles and tins of biscuits attached. The boat's occupants managed to recover two of the jackets from the sea. At 11:45 a Portuguese plane dropped a cylinder containing a message that help would arrive soon and a chart with the boat's position marked. North easterly trade winds had blown the boat much further south than Anson had estimated: about 100 miles (160 km) off the West African coast at 34°00′N 11°45′W / 34.000°N 11.750°W. The boat continued to sail east southeast.[1]

Help did not immediately come. On 24 July about 18:30 an aeroplane was sighted overhead heading northeast but it made no contact with the boat. Deaths continued throughout 23, 24 and 25 July and the surviving crew continued to commit their bodies to the sea. At 10:00 on 25 July the mast of a ship was sighted and Anson burnt distress flares to attract her attention. This was a Portuguese Navy Pedro Nunes-class aviso, NRP Pedro Nunes, which rescued the surviving occupants and hoisted the boat aboard.[1] The aviso had been quartering the coordinates provided by the aircraft, and was about to abandon the search when she sighted Clarke's flares.[13]

By this time 10 men had died in No. 6 boat.[16] The remaining sick men were admitted to the Pedro Nunes's sick bay, but one of the assistant stewards died shortly afterward.[13] They aviso reached Lisbon on 26 July and the wounded were transferred to hospital, where two more men died.[1]

The survivors from Boat No. 6 had suffered cold, lack of sleep, food and water and lost a great deal of weight. 20 days' exposure to salt water had afflicted their skin and Mary Ferguson was suffering from 48 salt water boils. She and Traunter remained in Lisbon until they were judged fit enough to travel. At the end of August a Douglas DC-3 flew them from Lisbon to Bristol, England. Ferguson almost immediately fulfilled her intention to join the WRNS, and served at Devonport for the remainder of the war.[13]

Honours and monuments

editIn November 1942 Chief Officer Eric Pearce, First Officer Michael Tallack and Second Officer John Anson were all awarded the MBE and Boatswain John Gray and passenger Mary Ferguson were awarded the BEM. Ship's carpenter Alexander Sutherland and Captain Charles Low, who had been Master of the Lylepark, received commendations. The London Gazette commended Pearce for "outstanding leadership... steady discipline and [keeping] everyone in good heart".[17] It commended Anson for "skilful seamanship... and [overcoming] many difficulties" in charge of an open boat for 20 days on the open sea. The London Gazette commended Ferguson for "great courage... nursing four injured men... [making] no fuss... and her general behaviour during the 20 days' ordeal... was excellent". It said Gray "showed great skill and initiative... and was responsible for saving many lives".[18] In 1943 Third Officer Richard Clarke, who had been in No. 2 Boat, was also awarded the MBE. The London Gazette said that "It was due to the courage, skill and fortitude of Mr Clarke during the latter part of the voyage that the boat was brought to safety."[16]

Lloyd's of London awarded Pearce and Ferguson Lloyd's War Medal for Bravery at Sea.[19][20]

Members of Almeda Star's crew who were killed are commemorated in the Second World War section of the Merchant Navy War Memorial at Tower Hill in London. One member of Avila Star's crew, 17-year-old Donald Black, is buried in the British Protestant Churchyard at Ponta Delgada. Three more are buried in the British Cemetery at St. George's Church, Lisbon: Assistant Steward William Clarke, Donkeyman Charles Ellis and Third Engineer Raymond Girdler.[21]

Ferguson's WRNS uniform jacket, bearing her medal ribbons, is now an exhibit in the Imperial War Museum.[22]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Blue Star's S.S. "Avila Star" 1". One of The Luxury Five. Blue Star on the Web. 26 November 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "Blue Star's S.S. "Avelona Star"". One of The Luxury Five. Blue Star on the Web. 8 October 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ a b Harnack 1938, p. 425.

- ^ Taffrail 1973, p. 66.

- ^ Lloyd's Register, Steamships and Motor Ships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1933. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Talbot-Booth 1942, p. 438.

- ^ a b c Lloyd's Register, Steamships and Motor Ships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1934. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Hoppe, Klaus. "Maierform" (in German). Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy OL.9". Shorter Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hague, Arnold. "Avila Star". Ship Movements. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy WS.9C". Shorter Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Convoy CT.4". Shorter Convoy Series. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mary "Johnnie" Ferguson". The Times. 8 July 2006.

- ^ Asmussen, John (2000–2009). "Hilfskreuzer (Auxiliary Cruiser) Michel". Bismarck & Tirpitz. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Helgason, Guðmundur (1995–2014). "Avila Star". uboat.net. Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood". London Gazette. 29 January 1943. p. 603. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood". London Gazette. 20 November 1942. p. 5105. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood". London Gazette. 20 November 1942. p. 5106. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ de Neumann, Bernard (19 January 2006). "Lloyd's War Medal for Bravery at Sea (Part One)". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ de Neumann, Bernard (19 January 2006). "Lloyd's War Medal for Bravery at Sea (Part Two)". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Hague, Arnold. "Crew lost from the SS Avila Star". Convoy OS.33. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "Jacket, WRNS: Petty Officer Ferguson, BEM, LWM". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

Sources and further reading

edit- Harnack, Edwin P (1938) [1903]. All About Ships & Shipping (7th ed.). London: Faber and Faber.

- "Taffrail" (Henry Taprell Dorling) (1973). Blue Star Line at War, 1939–45. London: W. Foulsham & Co. pp. 9, 40, 66–67. ISBN 0-572-00849-X.

- Talbot-Booth, E.C. (1942) [1936]. Ships and the Sea (Seventh ed.). London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. Ltd.

- Turner, J.F. (1963). A Girl Called Johnnie: Three weeks in an open boat. London: George Harrap & Co.

External links

edit- Helgason, Guðmundur (1995–2014). "Avila Star". Crew lists from ships hit by U-boats. Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "Saved by an oar, Liverpool officer on Avila Star, Merseyside survivors". Liverpool Daily Post. Old Mersey Times. 28 July 1942. Retrieved 12 August 2014.