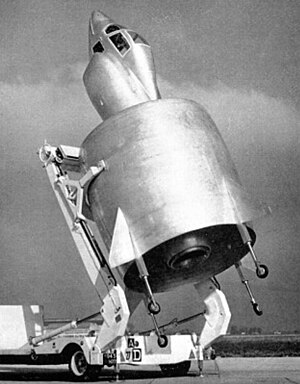

The SNECMA C.450 Coléoptère (meaning "beetle" in French, descended from Greek for "sheathed wing") was a tail-sitting vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft designed by the French company SNECMA and manufactured by Nord Aviation. While work on the aircraft proceeded to the test flying phase, the project never progressed beyond experimental purposes.

| C.450 Coléoptère | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Tail-sitting research aircraft |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | SNECMA and Nord |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Number built | 1 |

| History | |

| First flight | 6 May 1959 |

The Coléoptère was one of multiple efforts to produce a viable VTOL aircraft being conducted around the world throughout the 1950s. SNECMA had previously experimented with several wingless test rigs, known as the Atar Volant, which influenced the design. In terms of its general configuration, the Coléoptère was a single-person aircraft with an unusual annular wing; the aircraft was designed to take-off and land vertically, therefore requiring no runway and very little space. Performing its maiden flight during December 1958, the sole prototype was destroyed on its ninth flight on 25 July 1959. While there were intentions at one stage for a second prototype to be produced, financing was never sourced.

Development

editBackground

editDuring the 1950s, aircraft designers around the world engaged in programmes to develop fixed-wing aircraft that could not only perform both a vertical take-off and landing (VTOL), but transition into and out of conventional flight as well. As observed by the aviation author Francis K. Mason, a combat aircraft that possessed such qualities would have effectively eliminate the traditional reliance on relatively vulnerable runways by taking off and landing vertically as opposed to the conventional horizontal approach.[1] Accordingly, the development of viable vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft was particularly attractive to military planners of the early postwar era.[2] As the thrust-to-weight ratio of turbojet engines increased sufficiently for a single engine be able to lift an aircraft, designers began to investigate ways of maintaining stability while an aircraft was flying in the VTOL stage of flight.[3]

One company that opted to engage in VTOL research was the French engine manufacturer SNECMA who, beginning in 1956, built a series of wingless test rigs called the Atar Volant. Only the first of these was unpiloted and the second flew freely, both stabilized by gas jets on outrigger pipes. The third had a tilting seat to allow the pilot to sit upright when the fuselage was level and had the lateral air intakes planned for the free flying aircraft, though it always operated attached to a movable cradle. The pilot for these experiments was Auguste Morel. However, the Atar Volant was not an end onto itself; its long term purpose was to serve as precursors to a larger fixed-wing aircraft.[4]

Separately to the internal work, substantial influence on the direction of development came from the Austrian design engineer Helmut von Zborowski, who had designed an innovative doughnut-shaped annular wing that could function "as power plant, airframe of a flying wing aircraft and drag-reducing housing". It was theorised that such a wing could function as a ramjet engine and propel an aircraft at supersonic speeds, suitable for an interceptor aircraft.[2] SNECMA's design team decided to integrate this radical annual wing design into their VTOL efforts. Accordingly, from this decision emerged the basic configuration of the C.450 Coléoptère.[2]

Flight testing

editDuring early 1958, the completed first prototype arrived at Melun Villaroche Aerodrome ahead of testing. The eye-catching design of the Coléoptère rapidly made waves in the public consciousness, even internationally; author Jeremy Davis observed that the aircraft had even influenced international efforts, having allegedly motivated the United States Navy to contract American helicopter manufacturer Kaman Aircraft to design its own annular-wing vehicle, nicknamed the Flying Barrel.[2] In December 1958, the Coléoptère first left the ground under its own power, albeit while attached to a gantry; Morel was at the aircraft's controls.[3] Several challenging flight characteristics were observed, such as the tendency for the aircraft to slowly spin on its axis while in a vertical hover; Morel also noted that the vertical speed indicator was unrealistic and that the controls were incapable of steering the aircraft with precision while performing the critical landing phase. Dead-stick landings were deemed to be an impossibility.[2]

Morel conducted a total of eight successful flights, attaining a recorded maximum altitude of 800 m (2,625 ft). One of these flights involved a display of the aircraft's hover performance before an assembled public audience.[5] The ninth flight, on 25 July 1959, was planned to make limited moves towards entering horizontal flight; however, hindered by insufficient instrumentation and a lack of visual benchmarks, the aircraft became too inclined and too slow to maintain its altitude. Morel was unable to regain control amid a series of wild oscillations, opting to activate the ejection seat to escape the descending aircraft at only 150 m (492 ft).[2] He survived but was badly injured, while the aircraft itself was destroyed. While plans for a second prototype had been mooted at one stage, such ambitions ultimately never received the funding to proceed.[3]

Design

editThe Coléoptère featured a central core akin to the Atar Volant, but differed in that the fuselage was surrounded by an annular wing greatly resembling the proposals made by von Zborowski.[3] Aerodynamic control and stability was regulated by a series of four triangular winglets, which were installed upon the outwards side of the annual wing; however, these were only effective during conventional horizontal flight. Instead, control while hovering was provided by a series of deflecting vanes within the engine exhaust.[2] The undercarriage of the Coléoptère consisted of four relatively compact castored wheels.[3]

The pilot controlled the aircraft from within an enclosed cockpit; however, the pilot's position was somewhat unorthodox.[2] To accommodate the changing orientation of the aircraft between vertical and horizon flight, the pilot was seated upon an ejector seat that would tilt appropriately to match the flight mode of the aircraft, moving so that they would be seated nearly-upwards during the vertical phase of flight, such as landing and taking-off. The intakes for the powerplant, a single SNECMA Atar axial-flow turbojet engine were positioned on either side of the cockpit.[3] While the aircraft had been designed by SNECMA, the majority of the manufacturing process was performed by another French aircraft company, Nord Aviation.[4]

Specifications

editData from Les Avions Francais de 1944 à 1964[3]

General characteristics

- Crew: One

- Length: 8.02 m (26 ft 4 in)

- Wingspan: 4.51 m (14 ft 10 in) including fins

- Diameter: 3.20 m (10 ft 6 in)

- Max takeoff weight: 3,000 kg (6,614 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Atar EV (101E) axial-flow turbojet, 36.3 kN (8,200 lbf) thrust

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Mason 1967, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davis, Jeremy (July 2012). "Cancelled: Vertical Flyer". Air & Space Magazine.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gaillard (1990). p. 200.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Gaillard (1990). p. 180.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Haimes, Brian J. (15 November 2006). "The Coleopter - a revolutionary experimental aircraft". New Scientist.

Bibliography

edit- Buttler, Tony & Delezenne, Jean-Louis (2012). X-Planes of Europe: Secret Research Aircraft from the Golden Age 1946-1974. Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications. ISBN 978-1-902-10921-3.

- Carbonel, Jean-Christophe (2016). French Secret Projects. Vol. 1: Post War Fighters. Manchester, UK: Crecy Publishing. ISBN 978-1-91080-900-6.

- Cuny, Jean (1989). Les avions de combat français, 2: Chasse lourde, bombardement, assaut, exploration [French Combat Aircraft 2: Heavy Fighters, Bombers, Attack, Reconnaissance]. Docavia (in French). Vol. 30. Ed. Larivière. OCLC 36836833.

- Gaillard, Pierre (1990). Les Avions Francais de 1944 à 1964. Paris: Éditions EPA. p. 200. ISBN 2-85120-350-9.

- Mason, Francis K. The Hawker P.1127 and Kestrel (Aircraft in Profile 93). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1967.

- Roux, Robert J. (May 1977). "Atar Volant et Coleoptère (2): de drôles de bêtes du temps passé" [Atar Volant and Coléoptère, Part 2: Funny Beasts from the Past]. Le Fana de l'Aviation (in French) (90): 6–9. ISSN 0757-4169.