SMS Leipzig ("His Majesty's Ship Leipzig")[a] was the sixth of seven Bremen-class cruisers of the Imperial German Navy, named after the city of Leipzig. She was begun by AG Weser in Bremen in 1904, launched in March 1905 and commissioned in April 1906. Armed with a main battery of ten 10.5 cm (4.1 in) guns and two 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes, Leipzig was capable of a top speed of 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph).

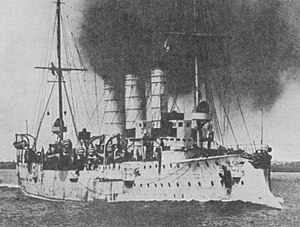

Leipzig underway before the war

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Leipzig |

| Namesake | Leipzig |

| Builder | AG Weser, Bremen |

| Laid down | 1904 |

| Launched | 21 March 1905 |

| Commissioned | 20 April 1906 |

| Fate | Sunk at the Battle of the Falkland Islands, 8 December 1914 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Bremen-class light cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | Length overall: 111.1 meters (365 ft) |

| Beam | 13.3 m (43.6 ft) |

| Draft | 5.61 m (18.4 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) |

| Range | 4,690 nmi (8,690 km; 5,400 mi) at 12 kn (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Leipzig spent her career on overseas stations; at the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, she was cruising off the coast of Mexico. After rejoining with the East Asia Squadron, she proceeded to South American waters, where she participated in the Battle of Coronel, where the German squadron overpowered and sank a pair of British armored cruisers. A month later, she again saw action at the Battle of the Falkland Islands, which saw the destruction of the East Asia Squadron. Leipzig was chased down and sunk by the cruisers HMS Glasgow and HMS Cornwall; the majority of her crew was killed in the battle, with only 18 survivors.

Design

editThe German 1898 Naval Law called for the replacement of the fleet's older cruising vessels—steam corvettes, unprotected cruisers, and avisos—with modern light cruisers. The first tranche of vessels to fulfill this requirement, the Gazelle class, were designed to serve both as fleet scouts and as station ships in Germany's colonial empire. They provided the basis for subsequent designs, beginning with the Bremen class that was designed in 1901–1903. The principle improvements consisted of a larger hull that allowed for an additional pair of boilers and a higher top speed.[1][2]

Leipzig was 111.1 meters (365 ft) long overall and had a beam of 13.3 m (44 ft) and a draft of 5.61 m (18.4 ft) forward. She displaced 3,278 metric tons (3,226 long tons) as designed and up to 3,816 t (3,756 long tons) at full load. The ship had a minimal superstructure, which consisted of a small conning tower and bridge structure. Her hull had a raised forecastle and quarterdeck, along with a pronounced ram bow. She was fitted with two pole masts. She had a crew of 14 officers and 274–287 enlisted men.[3]

Her propulsion system consisted of two triple-expansion steam engines driving a pair of screw propellers. Steam was provided by ten coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers, which were vented through three funnels located amidships. Her propulsion system was rated at 10,000 metric horsepower (9,900 ihp) for a top speed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph). Leipzig carried up to 860 t (850 long tons) of coal, which gave her a range of 4,690 nautical miles (8,690 km; 5,400 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[3]

The ship was armed with a main battery of ten 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/40 guns in single mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle; six were located on the broadside, three on either side; and two were placed side by side aft. The guns could engage targets out to 12,200 m (13,300 yd). They were supplied with 1,500 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun. For defense against torpedo boats, she carried ten 3.7 cm (1.5 in) Maxim guns in individual mounts. She was also equipped with two 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes with five torpedoes. They were submerged in the hull on the broadside. She was also fitted to carry fifty naval mines.[3][4]

The ship was protected by a curved armored deck that was up to 80 mm (3.1 in) thick; it sloped down at the sides to provide a measure of protection against enemy fire. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides, and the guns were protected by 50 mm (2 in) thick gun shields.[5]

Service history

editLeipzig was ordered under the contract name "N"[b] and was laid down at the AG Weser shipyard in Bremen on 12 July 1904 and launched on 21 March 1905, after which fitting-out work commenced. Work on the ship was completed, save the installation of her armament, by February 1906, when she underwent builder's trials. The ship then moved to Wilhelmshaven to have her guns installed. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 20 April 1906 for sea trials that lasted until mid-June. During this period, Fregattenkapitän (FK—Frigate Captain) Franz von Hipper served as the ship's first commanding officer. The ship concluded the initial period of service as the escort for Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was traveling on his annual summer cruise aboard the HAPAG steamer Hamburg. Hipper thereafter left the ship.[6][7]

Peacetime career in East Asia

editLeipzig was assigned to the East Asia Squadron, and her crew began preparations for the voyage overseas on 19 August. She sailed from Wilhelmshaven on 8 September and, after passing through the Dutch East Indies, arrived in Hong Kong on 6 January 1907. There, she met the protected cruiser Hansa, another member of the East Asia Squadron. From 25 January to 10 March, Leipzig lay as a guard ship at Qingdao, the capital of the Jiaozhou Bay Leased Territory. She later steamed up the Yangtze river with the squadron commander aboard, Vizeadmiral (VAdm—Vice Admiral) Carl von Coerper; the gunboat Tiger and the torpedo boat S90 accompanied Leipzig on the trip. In June, she joined the rest of the cruisers of the squadron for a tour of northern ports in the region. In the first half of 1908, the East Asia Squadron embarked on another lengthy cruise in northern East Asian waters. Leipzig made a shorter voyage in the Yellow Sea in August; that month, Korvettenkapitän (KK—Corvette Captain) Richard Engel took command of the ship. In September and October, she visited Shanghai, China, and made another trip up the Yangtze. On 17 November, she represented Germany at a major naval review held in Kobe, Japan. That month, KK Karl Heuser relieved Engel as the ship's captain.[7]

Leipzig was dry-docked at Hong Kong for periodic maintenance in January 1909, and while there, she received orders to sail to German Samoa after the work was completed. Unrest against German rule threatened to break out, and the colonial governor, Wilhelm Solf, requested assistance from the East Asia Squadron. From Hong Kong, she proceeded to Manila in the Philippines; there, Coerper came aboard the ship for the voyage to Samoa. The ship arrived in Apia, the capital of German Samoa, on 19 March. By the 28th, she had been joined by the light cruiser Arcona and the gunboat Jaguar, along with the steamer Titania, which carried a contingent of 100 local police. The local chief who had led the movement and some of his supporters were taken aboard Jaguar to Saipan, where they were exiled. The ships patrolled off Samoa through April, but by early May, the ships began to disperse. Arcona and Titania departed on 6 May, while Leipzig took Coerper to Suva, Fiji, stopping there from 14 to 17 May. There, he transferred to another vessel to return home. Leipzig then briefly returned to Samoa, though she was replaced by the unprotected cruiser Condor on 21 May. From there, Leipzig steamed to Pago Pago in American Samoa, made a brief stop in Apia, before departing for Qingdao, arriving there by way of Pohnpei and Manila on 29 June. For the rest of the year, Leipzig cruised with the squadron flagship, the armored cruiser Scharnhorst, in northern waters.[8]

In early 1910, Leipzig and Scharnhorst met the gunboat Luchs in Hong Kong, and the three vessels embarked on a voyage south. Leipzig and Scharnhorst cruised together, at times with Luchs, to visit Siam and various ports in the South China Sea. During this period, in February, FK Hermann Schröder arrived to take Heuser's place as the ship's commander. The two cruisers then steamed back north to visit Japan in April and May. Leipzig made another voyage up the Yangtze in July, steaming as far as Hankou, where unrest had broken out. Leipzig and the armored cruiser Gneisenau steamed to Calcutta, India, in early 1911 to meet Crown Prince Wilhelm, who was on a tour of East Asia. The ships arrived there on 31 January, but an outbreak of plague in the area led Wilhelm to cancel the rest of his trip. In March, the new squadron commander, Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Günther von Krosigk, came aboard the ship to make a visit to Japan, where he met Emperor Meiji. Over the following months, Leipzig visited a series of ports in Japan and in Siberia. While she was in Vladimir Bay in Russia in mid-August, Schröder learned of heightened tensions with France as a result of the Agadir Crisis; the Russians had severed the telegraph lines, however, so he could not communicate with Germany. The ship received a garbled wireless message that indicated Krosigk was to deploy his squadron to the Indian Ocean, but seeking confirmation, he dispatched Leipzig to Vladivostok, Russia, despite the risk of entering the port of France's ally. Leipzig remained in the port from 15 to 18 August, exchanging telegraphs with Germany; by that time, the crisis had passed, and Krosigk decided to take his squadron south, through the Yellow Sea, before arriving in Qingdao on 15 September.[9]

On 10 October, the 1911 Revolution broke out against Qing rule in China; since the unrest threatened foreign interests in the country, Krosigk deployed the ships of the squadron to defend German nationals, as did several other navies. Leipzig was sent to reinforce the gunboats Tiger and Vaterland, while Gneisenau was sent to Nanking and the gunboat Iltis to Hankou. Command of the international force assembled in China was given to the Japanese Rear Admiral Kawashima Reijirō. The ships sent landing parties ashore to defend foreign holdings, and they evacuated women and children to Shanghai, though Chinese attacks on foreigners did not materialize. Leipzig, which by then had Krosigk aboard, was forced to leave Hankou in November due to falling water levels in the Yangtze, and she joined Gneisenau in Shanghai. Leipzig spent the next several months cruising between Qingdao and the areas of the country beset by revolution. These activities concluded in early August 1912, and on 7 August, she began a trip that included stops in Vladivostok, Russia, and various ports in Japan. While there, she was present for the funeral ceremonies for Meiji. By the end of the year, Leipzig had returned to Shanghai.[10]

In early 1913, she visited cities along the central Chinese coast. In March, Johann-Siegfried Haun took command of the ship; he was to be her final captain. Her crew observed heavy fighting between imperial and republican forces around Nanking in July and August. The ship returned to Qingdao in September for an overhaul that lasted into October. She thereafter cruised south and visited the Philippines. In May 1914, Leipzig received orders to replace the light cruiser Nürnberg, which was cruising off the Pacific coast of Mexico to protect German interests during the Mexican Revolution. She arrived off Mazatlán, Mexico, on 7 July, where she met Nürnberg and the cruiser Dresden; the three German cruisers operated in concert with vessels from other navies to evacuate foreigners in the country. Because telegraph lines had been cut in Mexico, the German vessels did not learn of the July Crisis in Europe until 31 July, by which time World War I had broken out. Leipzig transferred forty civilians to the neutral US armored cruiser USS California and then made preparations for wartime operations.[11]

World War I

editLeipzig anchored at Magdalena Bay in Mexico to await developments, and on 5 August, Haun learned of the state of war between Germany and the Triple Entente. The established mobilization plan called for the ships of the East Asia Squadron to unite, but Leipzig lacked collier support. She stopped in San Francisco to take on coal, but was unable to fully replenish her bunkers due to the United States' strict adherence to neutrality laws. Haun therefore decided to embark on a commerce raiding campaign against British merchant shipping. The lack of suitable targets led Haun to move south to the Gulf of California on 17 August to take on more coal. A week later, Leipzig sank a British freighter carrying sugar and then proceeded to the Peruvian coast by the 28th. She stopped in Guaymas in neutral Mexico to take on a fresh load of coal on 8 September.[12][13][14] She got underway two days later, headed further south in accordance with instructions from the German naval command, and on 11 September she stopped and sank the British oil tanker Elsinore. She called in the Galápagos Islands to take coal from a German merchant ship and put Elsinore's crew ashore.[15][16] Reports of a British squadron in the area forced Leipzig to leave.[12][13][14]

The ship thereafter stopped to allow the crew to clean her badly fouled boiler tubes, before resuming her voyage to Easter Island. There, on 14 October, she joined the rest of the East Asia Squadron, by which time the unit was under the command of VAdm Maximilian von Spee. By that time, Leipzig had accumulated a group of three colliers. On 18 October, the Squadron departed, bound for South America; they stopped in the Juan Fernández Islands while en route, and by 26 October, they were approaching Mas a Fuera. They then steamed to Valparaiso, Chile, where they received intelligence that indicated that the British cruiser HMS Glasgow was anchored in Coronel. Spee decided to proceed to Coronel to ambush the British ship when it left port. Glasgow was in fact joined by the armored cruisers HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth.[17][18]

Battle of Coronel

editWhile patrolling off Coronel, Leipzig stopped a Chilean barque and searched her, but since she was a neutral vessel, and not carrying contraband, the Germans let her go. At 16:00 on 1 November, Leipzig spotted a column of smoke in the distance, followed by a second ship at 16:17, and a third at 16:25. The British spotted Leipzig at approximately the same time, and the two squadrons formed into lines of battle. Leipzig was the third ship in the German line, behind the two armored cruisers. At 18:07, Spee issued the order "Fire distribution from left", meaning that each ship would engage its opposite number; the Germans fired first, at 18:34.[19]

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau quickly wrecked their British counterparts, while Leipzig fired at Glasgow without success. At 18:49, Glasgow hit Leipzig, but the shell was a dud and did not explode. Leipzig and Dresden hit Glasgow five times before Spee ordered Leipzig to close with the stricken Good Hope and torpedo it. A rain squall obscured the ship, and by the time Leipzig reached Good Hope's position, the latter had sunk. Unaware of the sinking of Good Hope, no rescue operations were mounted by Leipzig's crew. By 20:00, Leipzig encountered Dresden in the gathering darkness, and the two initially mistook each other for hostile warships, though they quickly established their identity. Leipzig emerged from the battle essentially unscathed, and with no wounded crewmen.[20]

In the aftermath of the Battle of Coronel, Spee decided to return to Valparaiso to receive further orders; while Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Nürnberg went into the harbor, Leipzig and Dresden escorted the colliers to Mas a Fuera. The rest of the East Asia Squadron joined them there on 6 November; the cruisers restocked their coal and other supplies. On 10 November, Leipzig and Dresden were sent to Valparaiso, arriving on the 13th. Five days later, they rejoined the Squadron approximately 250 nautical miles (460 km; 290 mi) west of Robinson Crusoe Island; the unified Squadron then proceeded to the Gulf of Penas, arriving on 21 November. There, they coaled and prepared to make the long voyage around Cape Horn. The British, shocked by their defeat at Coronel, had meanwhile dispatched the powerful battlecruisers HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible, under the command of Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee, to hunt down and destroy Spee's ships. They departed Britain on 11 November and reached the Falkland Islands on 7 December, having been joined on the way by the armored cruisers Carnarvon, Kent, and Cornwall and the light cruisers Bristol and the battered Glasgow.[21]

Battle of the Falkland Islands

editOn 26 November, the East Asia Squadron departed the Gulf of Penas, bound for Cape Horn and the Atlantic and reached the Cape on 2 December. While off the Cape, Leipzig took the Canadian sailing ship Drummuir as a prize; the ship was carrying 2,750 t (2,710 long tons; 3,030 short tons) of coal, which was transferred to the colliers Baden and Santa Isabel at Picton Island. On the night of 6 December, Spee held a conference with the ship commanders to discuss his proposed attack on the Falklands; Haun, along with the commanders from Gneisenau and Dresden, opposed the plan and favored bypassing the Falklands to wage commerce war off La Plata. Nevertheless, Spee made the decision to attack the Falklands on the morning of 8 December.[22]

The Germans approached Port Stanley, the capital of the Falklands, early on the morning of 8 December; the British quickly spotted them, and raised steam to go out and meet them. Spee initially thought the smoke clouds to be the British burning their coal stocks to prevent the Germans from seizing them. Upon realizing the presence of the powerful British squadron, he broke off the attack and turned to flee. The British quickly steamed out of the harbor in pursuit. By 12:55, the battlecruisers had caught up to the retreating Germans, and opened fire on Leipzig, the last ship in the German line, though she was not hit. Spee signaled "Leipzig released" at 13:15 and five minutes later instructed the other light cruisers to flee while Scharnhorst and Gneisenau turned on their pursuers, in the hope that he could cover their escape.[23] In response, Sturdee sent his cruisers to chase down Nürnberg, Dresden, and Leipzig.[17][24]

Glasgow pursued Leipzig, and quickly caught up, opening fire by 14:40. After about twenty minutes of firing, Leipzig was hit; she turned to port to open the range, before turning to starboard in order to bring her full broadside into action. In the ensuing action, both ships were hit several times, forcing Glasgow to break off and fall behind the more powerful armored cruisers. Leipzig was battered severely by Cornwall and Glasgow and set on fire; she nevertheless remained in action and continued to fight. In the course of the engagement, Leipzig hit Cornwall eighteen times, causing a significant list to port. She fired three torpedoes at the British ships, but failed to score any hits with them. At 19:20, Haun issued the order to scuttle his wrecked ship; the British approached and opened fire on the stricken cruiser at close range, killing large numbers of the crew. The British also destroyed a cutter filled with survivors, killing all of them. Leipzig finally capsized and sank at 21:05, with Haun still aboard. Only eighteen men were pulled from the freezing water.[17][25]

Notes

editFootnotes

edit- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

Citations

edit- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 2, p. 124.

- ^ Nottelmann, pp. 108–110.

- ^ a b c Gröner, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 211.

- ^ Gröner, p. 102.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 102–104.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 212.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 213.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 211, 213.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 213–214.

- ^ a b Marley, p. 634.

- ^ a b Staff, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Bisher, p. 15.

- ^ Fayle, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 214.

- ^ Staff, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Staff, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Staff, pp. 34–37, 39.

- ^ Staff, pp. 58–60.

- ^ Staff, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Staff, pp. 62–66.

- ^ Halpern, p. 99.

- ^ Staff, pp. 73–76.

References

edit- Bisher, Jamie (2016). The Intelligence War in Latin America, 1914–1922. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3350-6.

- Fayle, C Ernest (1920). Seaborne Trade. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I: The Cruiser Period. London: John Murray. OCLC 1184620170.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1991). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1557503527.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 2. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8364-9743-5.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 5. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0456-9.

- Marley, David F. (1998). Wars of the Americas. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-837-5.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). "The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84884-182-6.

Further reading

edit- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.

External links

edit- "S.M.S. Leipzig (1905), Kleiner Kreuzer der Kaiserlichen Marine, technische Angaben und Geschichte in alten Postkarten" [S.M.S. Leipzig (1905), Small Cruiser of the Imperial Navy, Technical Details and History in Old Postcards]. www.deutsche-schutzgebiete.de (in German). Retrieved 20 December 2023.