The Diocese of Palm Beach (Latin: Dioecesis Litoris Palmensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory, or diocese, of the Catholic Church in eastern Florida in the United States The patron saint of the diocese is Mary, mother of Jesus, under the title Queen of the Apostles.

Diocese of Palm Beach Dioecesis Litoris Palmensis | |

|---|---|

Cathedral of St. Ignatius Loyola | |

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Ecclesiastical province | Miami |

| Statistics | |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2022) 2,211,148 233,244 (10.5%) |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | June 16, 1984 |

| Cathedral | Cathedral of St. Ignatius Loyola |

| Patron saint | Our Lady, Queen of the Apostles[1] |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | Gerald Michael Barbarito |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Thomas Wenski |

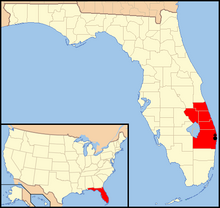

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| diocesepb.org | |

The Diocese of Palm Beach is a suffragan diocese in the ecclesiastical province of the metropolitan Archdiocese of Miami. As of 2023, the current diocesan bishop is Gerald Barbarito.

Statistics

editThe Diocese of Palm Beach serves 280,000 Catholics in 53 parishes and missions across five counties in southeastern Florida:

History

edit1500 to 1550

editThe first Catholic presence in present-day Florida was the expedition of the Spaniard Juan Ponce de León, who arrived somewhere on the Gulf Coast in 1513. Hostility from the native Calusa people prevented him from landing. De Leon returned to the region with a colonizing expedition in 1521, landing near either Charlotte Harbor or the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River. His expedition had 200 men, including several priests.[3]

In 1539, Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto, hoping to find gold in Florida, landed near present day Port Charlotte or San Carlos Bay. He named the new territory "La Bahia de Espiritu Santo," in honor of the Holy Spirit.[4] DeSoto led an expedition of 10 ships and 620 men. His company included 12 priests, there to evangelize the Native Americans. His priests celebrated mass almost every day.[4] Unwilling to attack such a large expedition, the Calusa evacuated their settlements near the landing area. The De Soto expedition later proceeded to the Tampa Bay area and then into central Florida.

The Spanish missionary Reverend Luis de Cáncer arrived by sea with several Dominican priests in present day Bradenton in 1549. Encountering a seemingly peaceful party of Tocobaga clan members, they decided to travel on to Tampa Bay. Several of the priests went overland with the Tocobaga while Cáncer and the rest of the party sailed to Tampa Bay to meet them.[5]

Arriving at Tampa Bay, Cáncer learned, while still on his ship, that the Tocobaga had murdered the priests in the overland party. Ignoring advice to leave the area, Cáncer went ashore, where he too was murdered.[5] The Spanish attempted to establish another mission in the Tampa Bay area in 1567, but it was soon abandoned.[6]

1550 to 1700

editThe first Catholics in Eastern Florida were a group of Spanish Jesuits who founded a mission in 1566 on Upper Matecumbe Key in the Florida Keys. After several years of disease and turbulent relations with the Native American inhabitants, the missionaries returned to Spain.[7]The Spanish attempted to establish another mission in the Tampa Bay area in 1567, but soon abandoned it.[8]

In 1571, Spanish Jesuit missionaries made an brief, unsuccessful trip to Northern Florida. Two years later, in 1573, several Spanish Franciscan missionaries arrived in present day St. Augustine. They established the Mission Nombre de Dios in 1587 at a village of the Timucuan people.[9] By 1606, Florida was under the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Havana in Cuba.

In 1565, the Spanish explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, the founder of Saint Augustine and Governor of Spanish Florida, brokered a peace agreement with the Calusa peoples. This agreement allowed him to build the San Antón de Carlos mission at Mound Key in what is now Lee County. Menéndez de Avilés also built a fort at Mound Key and established a garrison.

San Antón de Carlos was the first Jesuit mission in the Western Hemisphere and the first Catholic presence within the Venice area. Juan Rogel and Francisco de Villareal spent the winter at the mission studying the Calusa language, then started evangelizing among the Calusa in southern Florida. The Jesuits built a chapel at the mission in 1567. Conflicts with the Calusa soon increased, prompting Menéndez de Avilés to abandon San Antón de Carlos in 1569.[10]

1700 to 1800

editBy the early 1700's, the Spanish Franciscans had established a network of 40 missions in Northern and Central Florida, with 70 priests ministering to over 25,000 Native American converts.[11]

However, raids by British settlers and their Creek Native American allies from the Carolinas eventually shut down the missions. Part of the reason for the raids was that the Spanish colonists gave refuge to enslaved people who had escaped the Carolinas.[12] A number of Timucuan Catholic converts in Northern Florida were slaughtered during these incursions.

After the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, Spain ceded all of Florida to Great Britain for the return of Cuba. Given the antagonism of Protestant Great Britain to Catholicism, the majority of the Catholic population in Florida fled to Cuba.[13]

After the American Revolution, Spain regained control of Florida in 1784. from Great Britain.[14] In 1793, the Vatican changed the jurisdiction for Florida Catholics from Havana to the Apostolic Vicariate of Louisiana and the Two Floridas, based in New Orleans.[15]

1800 to 1870

editIn the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, Spain ceded all of Florida to the United States, which established the Florida Territory in 1821.[16] In 1825, Pope Leo XII erected the Vicariate of Alabama and Florida, which included all of Florida, based in Mobile Alabama.[17]

In 1850, Pope Pius IX erected the Diocese of Savannah, which included Georgia and all of Florida east of the Apalachicola River. In 1858, Pius IX moved Florida into a new Apostolic Vicariate of Florida and named Bishop Augustin Verot as vicar apostolic.[18] Since the new vicariate had only three priests, Vérot traveled to France in 1859 to recruit more. He succeeded in bringing back seven priests.[19] The first Catholic parish in Tampa, St. Louis, was founded in 1859.

In 1870, Pius IX elevated the Vicariate of Florida into the Diocese of St. Augustine and named Vérot as its first bishop.[20] The new diocese covered all of Florida except for the Florida Panhandle region. The Palm Beach area would remain part of two other Florida dioceses for the next 114 years.

Bishop John Moore of St. Augustine asked the Society of Jesus in 1889 to assume jurisdiction over all of South Florida. The Jesuits then sent Reverend Conrad M. Widman to present-day Palm beach in 1892 to serve as its first priest. He founded St. Ann Parish, the first parish in the diocese. The land for the church was donated by the developer Henry Flagler.[21][22]

1900 to 1990

editIn 1910, the first Catholic parish in Fort Pierce, Saint Anastasia, was founded. Six years later, the St. Joseph Mission was established in Stuart. By 1930, five parishes had been erected in the area. The Vincentian Fathers established the St. Vincent de Paul Regional Seminary in Boynton Beach, which would later by used by all the Florida diocese. When the Vatican elevated the Diocese of Miami to the Archdiocese of Miami in 1968, it moved Palm Beach and Martin Counties from the Diocese of St. Augustine.[22]

Pope John Paul II established the Diocese of Palm Beach on June 16, 1984, taking its territory from the Archdiocese of Miami and the Diocese of Orlando.[23][24] He appointed Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Daily of the Archdiocese of Boston as the first bishop of Palm Beach. Among his most noteworthy actions were the leading of anti-abortion prayers vigils at local women's health clinics. In 1990, John Paul II selected Daily to serve as bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn.

1990 to 2000

editIn June 1990, John Paul II appointed Bishop Joseph Symons of the Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee as the second bishop of Palm Beach.[25] In 1991, Symons authorized the taping of an exorcism for TV broadcast. The rite was performed by Reverend James J. LeBar and other priests on a 16-year-old girl identified as "Gina". Footage of the exorcism was then aired on ABC's 20/20 TV program. In allowing the taping, Symons said that he hoped it would help "counteract diabolical activities around us."[26] By 1995, the diocese had a Catholic population of approximately 200,000 in 46 parishes and five missions.[22]

In April 1998, a 53-year-old man informed Archbishop John C. Favalora that Symons had sexually abused him when he was an altar server decades earlier. When confronted with the allegations, Symons admitted his guilt. The Vatican immediately asked Bishop Robert N. Lynch of the Diocese of St. Petersburg to hear Symons' confession. During that session, Symons admitted that he had abused four other boys. He also said that he had confessed the abuses to a priest at the time, but the priest simply told Symons to avoid alcohol consumption of alcohol and refrain from having sex.[27] According to Lynch, the molestations all took place in Pensacola-Tallahassee.[28]

In June 1998, Lynch announced that John Paul II had accepted Symons' resignation as bishop of Palm Beach and had named Lynch as apostolic administrator of the diocese.[29][30][28] To replace Symons, John Paul II in November 1998 named Bishop Anthony O'Connell of the Diocese of Knoxville as the new bishop of Palm Beach.[31]

2000 to present

editOn March 8, 2002, O'Connell admitted that he had molested at least two students of St. Thomas Aquinas Preparatory Seminary in Hannibal, Missouri, during his 25-year career there.[32] That same day, O'Connell offered his resignation as bishop of Palm Beach to the Vatican. It was accepted by Pope John Paul II on March 13, 2002.[33][34]

John Paul II in September 2002 selected Bishop Seán O'Malley of the Diocese of Fall River as the new bishop of Palm Beach.[35] After less than a year in Palm Beach, the pope appointed O'Malley as archbishop of Boston.

The current bishop of the Diocese of Palm Beach is Gerald Barbarito, formerly bishop of the Diocese of Ogdensburg.[36] He was named by John Paul II in 2003.

Deborah True, the former parochial administrator for Holy Cross Church in Vero Beach, was arrested for embezzlement in September 2022. She was accused of stealing $1.5 million from the church, in collaboration with the pastor, Reverend Richard Murphy, from 2015 to 2020. Murphy died in 2020. True spent $500,000 of the stolen money on personal debts.[37]

Sex abuse

editThe family of a Lake Worth teenager reported to the diocese in 1998 that Reverend Edwin Collins had attempted to sexually assault him at Collins' residences. Collins was a retired priest from the Diocese of Rockville Centre. The diocese immediately confronted Collins with the accusations, prompting him to resign from public ministry.[38]

In May 2002, Kelly Hoffman reported to the diocese that she had been sexually abused by Reverend Frank Flynn, starting at age 12 in 1978 and continuing for the next seven years. Flynn would passionately kiss and grope her at the end of counseling sessions. The diocese had also received complaints about Flynn seducing adult women when they were at vulnerable moments in their lives; one alleged victim was grieving a deceased husband. Flynn had returned to Ireland that same year, claiming health problems. When Flynn came back to Florida in 2004, Bishop O'Malley suspended him from ministry in the diocese.[39]

Police in September 2002 arrested Reverend Elias F. Guimaraes of Our Lady Queen of Peace Mission Church near Delray Beach of soliciting sex from a minor. Guimaraes had arranged online to meet a teenage boy at the beach, but he was arrested there in a police sting operation.[40] He pleaded guilty in federal court in January 2003 and was sentenced in April 2003 to 51 months in prison.[41][42] Guimaraes was deported to Brazil after his release from prison.

In January 2015, Reverend Jose Palimattom of Holy Name of Jesus Church in West Palm Beach, was arrested for possessing child pornography and showing images to a 14-year-old boy. The family spoke to Reverend John Gallagher, also at Holy Name, who contacted the diocese and notified police. Arresting officers discovered 40 pornographic images of preteen boys on the phone.[43] Palimattom was convicted, sentenced to six months in jail and was deported to India after his release.[44]

Gallagher sued the diocese for defamation in 2017, saying that it had retaliated against him for notifying the police about Paliamattom. Gallagher said that he had been locked out of the Holy Name rectory and refused an assignment there as pastor. The diocese said that he was not named pastor of Holy Name for other unrelated reasons.[45] Gallagher lost the case in lower courts and the US Supreme Court in April 2019 declined to review it.[46]

In September 2020, the family of an 11-year-old girl sued the diocese and All Saint's School in Jupiter. The plaintiffs said that the diocese and the school failed to protect her from repeated sexual abuse by another student in an unsupervised classroom on campus. The plaintiffs also alleged that the diocese protected the attacker because his parents were wealthy donors to the diocese.[47] The alleged abuse occurred between January and March 2020.[47] A sixth grade male was then charged with battery and lewd and lascivious molestation.[48]

Bishops

editBishops of Palm Beach

edit- Thomas Vose Daily (1984–1990), appointed Bishop of Brooklyn

- Joseph Keith Symons (1990–1998)

- Robert Nugent Lynch, Bishop of St. Petersburg (apostolic administrator 1998–1999.) - Anthony Joseph O'Connell (1999–2002)

- Seán Patrick O'Malley, OFM Cap. (2002–2003), appointed Archbishop of Boston (elevated to Cardinal in 2006)

- Gerald Michael Barbarito (2003–present)

High schools

edit- Cardinal Newman High School – West Palm Beach

- John Carroll Catholic High School – Fort Pierce

- Saint John Paul II Academy – Boca Raton

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Diocese of Palm Beach : About Us : About Us".

- ^ "Diocese of Palm Beach". Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Davis, T. Frederick (1935). "History of Juan Ponce de Leon's Voyages to Florida". Florida Historical Quarterly. 14 (1): 51–66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robert S. Weddle (2006). "Soto's Problems of Orientation". In Galloway, Patricia Kay (ed.). The Hernando de Soto Expedition: History, Historiography, and "Discovery" in the Southeast (New ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-8032-7122-7. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burnett, Gene (1986). Florida's Past, volume 1. Pineapple Press. p. 156. ISBN 1561641154. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "History of our Diocese". Catholic Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- ^ "History of the Parish 1556–1850". Basilica of St. Mary Star of the Sea. Archived from the original on 2014-05-29. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- ^ "History of our Diocese". Catholic Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- ^ "The Church and the Missions". St. Augustine: America's Ancient City. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "History | Florida State Parks". www.floridastateparks.org. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Expansion of Missions and Ranches". St. Augustine: America's Ancient City. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "The English Menace & African Resistance". St. Augustine: America's Ancient City. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "Introduction". St. Augustine: America's Ancient City. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "Introduction". St. Augustine: America's Ancient City. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "New Orleans (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "European Exploration and Colonization – Florida Department of State". dos.myflorida.com. Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- ^ "New Orleans (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ "Savannah (Diocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- ^ Michael V. Gannon, The Cross in the Sand (University of Florida, 1983) pp. 167-168.

- ^ "Bishop Jean Marcel Pierre Auguste Vérot [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ Beaulieu, Maurice (2021-09-16). "Oldest Palm Beach Church has rich history and promising future". Florida Catholic Media. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "History and Statistics : About Us : Diocese of Palm Beach". www.diocesepb.org. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ "Diocese of Palm Beach". Catholic-Hierarch. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Diocese of Palm Beach". Gcatholic. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Bishop Joseph Keith Symons [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ Steinfels, Peter (April 4, 1991). "Exorcism, Filmed With Priest's Consent, to Be Shown on TV". New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "Top South Florida News, Sports, Weather and Entertainment - South Florida Sun-Sentinel". sun-sentinel.com. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Handling Pedophilia". www3.trincoll.edu. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ^ Rozsa, Lori; Witt, April (June 2, 1998), "Catholic Bishop Resigns after Admitting to Sexual Abuse of Children", Miami Herald, retrieved May 1, 2019 – via BishopAccountability

- ^ "Bishop Anthony Joseph O'Connell [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ Ross, Brian; Schwartz, Rhonsa; Schecter, Anna (15 April 2008). "Victims: Pope Benedict Protects Accused Pedophile Bishops". ABC News. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Bishop Anthony Joseph O'Connell. Catholic-Hierarchy. Retrieved on April 17, 2010.[self-published source]

- ^ Diocese of Palm Beach. GCatholic. Retrieved on 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Seán Patrick Cardinal O'Malley [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ "Bishop Gerald Michael Barbarito [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ CNA. "Priest and parish administrator embezzled over $1 million from parish, police say". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "Case Missed in Review of Priests' Files Cleric Resigned after Boy Alleged Misconduct, Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, FL), September 7, 2002". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "Turbulent Year for Diocese, Church". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "Priest Accused of Soliciting Sex from Agent Posing As Teen, by Nicole Sterghos Brochu, Peter Franceschina, Tanya Weinberg, Noaki Schwartz and Diana Marrero, Sun-Sentinel [Fort Lauderdale FL], September 11, 2002". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "Priest Admits Guilt in Sex Case Internet Talks Led to Arrest in Sept. 2002, by Megan O'Matz and Peter Franceschina, Sun-Sentinel [Fort Lauderdale FL], January 16, 2003". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "Priest Sentenced in Online Sex Case Delray Cleric Gets 51 Months for Trying to Solicit Minor, by Jon Burstein, Sun-Sentinel, April 8, 2003". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "West Palm priest arrested after allegedly sharing porn images with boy". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ "Palm Beach County priest takes fight against Diocese to U.S. Supreme Court". WPTV News Channel 5 West Palm. 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ White, Ted (2017-01-11). "Catholic priest suing Diocese of Palm Beach". WPBF. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court rejects priest defamation case against Diocese of Palm Beach". WPTV News Channel 5 West Palm. 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2023-08-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burke, Peter; Gilmore, Chris (September 17, 2020). "Lawsuit claims All Saints Catholic School failed to protect student from sexual abuse in classroom". WPTV. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ "Student charged in case that led to sex-abuse lawsuit against Catholic school, diocese". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved 2023-08-11.