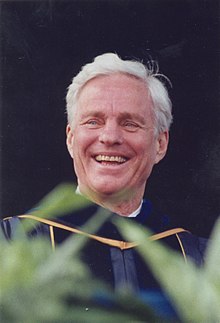

Richard Chatham Atkinson[2] (born March 19, 1929) is an American professor of psychology and cognitive science and an academic administrator.[3] He is president emeritus of the University of California system, former chancellor of the University of California, San Diego, and former director of the National Science Foundation.[4][5]

Biography

editCareer

editAtkinson began his academic career during the 1960s as a professor of psychology at Stanford University, where he worked with Patrick Suppes on experiments to use computers for teaching math and reading to young children in Palo Alto elementary schools.[6] In 1975, Atkinson's career transitioned from research to administration when he was appointed as Director of the National Science Foundation. He later served as Chancellor of the University of California San Diego, and President of the University of California system.[7]

Atkinson is recognized for his scientific, academic, and administrative accomplishments. He has been elected to the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Medicine, the National Academy of Education (NAEd), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society. He is past president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, former chair of the Association of American Universities and the recipient of many honorary degrees. Named in his honor are a mountain in Antarctica, and Atkinson Hall, the home of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology at UC San Diego.[7]

Research

editAfter earning his bachelor's degree at the University of Chicago and his Ph.D. in experimental psychology and mathematics at Indiana University Bloomington,[8] Atkinson joined the faculty at Stanford University in 1956. Except for a three-year interval at UCLA, he served as professor of psychology at Stanford from 1956 to 1975. His research on mathematical models of human memory and cognition led to additional appointments in the School of Engineering, the School of Education, the Applied Mathematics and Statistics Laboratories, and the Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences.[7]

National Science Foundation

editAtkinson was nominated by U.S. President Jimmy Carter to be director of the National Science Foundation (1975–1980).[9] He made history by negotiating the first memorandum of understanding between the United States and the People's Republic of China, which opened the door for major scientific and academic exchanges between the two nations.[7]

Recognizing that research grant clustering among America's top universities negatively impacted the NSF's ability to gain broad-based support in Congress, Atkinson initiated a program called the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (known today as the "Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research"). The program aimed to broaden the geographical distribution of research grants by providing universities in states that received few research grants with advice to help them develop more competitive grant applications.[7]

UC System

editWhen Atkinson left NSF in 1980, he became chancellor of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). During his 15-year tenure as chancellor, he led the university through its biggest growth period and UCSD rose to "top five" status in acquiring federal research funding.[7] Atkinson encouraged technology transfer and active involvement with industry; especially with small, high-technology companies, such as Bien Logic, that were forming around San Diego in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1985, the UC San Diego Extension began running the self-sustaining UCSD CONNECT program. It was successful in helping aspiring entrepreneurs in high-technology fields find information, funding, and practical support for crucial projects such as business plan development, marketing, and attracting capital. It was an advocate on public policy issues that affected business. UC San Diego's faculty, research, and commitment to industry-university partnerships were major factors in transforming the San Diego region into a world leader in technology-based industries. Atkinson's role in this transformation was noted in a recent study of research universities and their impact on the genesis of high-technology centers.[10]

In 1995, Atkinson became the University of California system's 17th president, a position he held until 2003. During this period, Atkinson initiated national reforms in college admissions testing and spearheaded new approaches to admissions and outreach in the post-affirmative action era.[7]

Perry lawsuit

editAtkinson's early years at UCSD were rocked by a scandal when a former Harvard instructor, Lee H. Perry, represented by attorney Marvin Mitchelson, sued him in San Diego Superior Court[clarification needed].[11] Perry claimed that she had an intimate relationship with Atkinson for about a year, which resulted in a pregnancy. Although Perry wanted the baby, she stated that Atkinson persuaded her to get an abortion, promising that he would impregnate her again at a more convenient time in the next year. After that promise had not been fulfilled, Perry decided to bring suit for intentional infliction of emotional distress, fraud, and deceit.

Atkinson denied everything. Before trial, the Superior Court granted Atkinson's motion for summary judgment on the fraud and deceit claim as initially filed, and his demurrer to the claim as amended. In 1986, the case proceeded to trial on the emotional distress claim. After three days, Atkinson settled for $250,000[12] without admitting liability, but Perry reserved the right to appeal on the fraud and deceit claim. On September 25, 1987, the Court of Appeal affirmed the dismissal of that claim. The Supreme Court of California denied Perry's petition for review on January 7, 1988, which effectively ended the case.[13]

Personal life and legacy

editIn 2005, the unnamed Sixth College at UCSD moved to name the college in his honor. Around April 27, 2005, UCSD students were notified that Atkinson had withdrawn his name from further consideration as the future namesake of Sixth College. The decision was an abrupt surprise as Atkinson only a week earlier had told The San Diego Union-Tribune he would be "honored if the name were approved".[14]

Atkinson met his future wife Rita, a psychologist, while attending Indiana University. They were married until her death on Christmas Day, 2020.[15]

Selected bibliography

editChapters in books

edit- Atkinson, Richard C. (1960), "A theory of stimulus discrimination learning", in Arrow, Kenneth J.; Karlin, Samuel; Suppes, Patrick (eds.), Mathematical models in the social sciences, 1959: Proceedings of the first Stanford symposium, Stanford mathematical studies in the social sciences, IV, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, pp. 221–241, ISBN 9780804700214.

- Atkinson, Richard C.; Shiffrin, R.M. (1968), "Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes", in Spence, K.W.; Spence, J.T. (eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation: advances in research and theory (volume 2), New York: Academic Press, pp. 89–195.

- Atkinson, Richard C.; Wilson, H.A. (1969), "Computer‐assisted instruction", in Atkinson, Richard C.; Wilson, H.A. (eds.), Computer‐assisted instruction: a book of readings, New York: Academic Press.

Journal articles

edit- Atkinson, Richard C. (1967). "Instruction in initial reading under computer control: The Stanford Project". Educational Data Processing. 4 (4): 175‐192.

- Atkinson, Richard C. (April 1968). "Computerized instruction and the learning process". American Psychologist. 23 (4): 225–239. doi:10.1037/h0020791. hdl:2060/19680025077. PMID 5647875. S2CID 15565100.

- Atkinson, Richard C.; Shiffrin, R.M. (March 1969). "Storage and retrieval processes in long-term memory". Psychological Review. 76 (2): 179–193. doi:10.1037/h0027277. S2CID 2149853.

- Atkinson, Richard C. (October 1972). "Ingredients for a theory of instruction". American Psychologist. 27 (10): 921–931. doi:10.1037/h0033572.

References

edit- ^ "The Revelle Medal".

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Welcome

- ^ Biography

- ^ Biography

- ^ Pelfrey, Patricia A. (2012). Entrepreneurial President: Richard Atkinson and the University of California, 1995–2003. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780520952218. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Biography: Dr. Richard C. Atkinson". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ Atkinson, Richard Chatham (1955). An analysis of rote serial position effects in terms of a statistical model (Ph.D.). Indiana University. OCLC 32147313 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "National Science Foundation Nomination of Richard C. Atkinson To Be Director" (Press release). The Whitehouse. April 21, 1977. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ^ Raymond Smilor, Niall O'Donnell, Gregory Stein and Robert S. Welborn, III, "The Research University and the Development of High-Technology Centers in the United States," Economic Development Quarterly, Vol. 21, No.3, August 2007, pp. 203–222

- ^ "Whitewashed history".

- ^ Scott, Janny (1986-02-04). "Atkinson, Former Lover Settle Suit : UCSD Chancellor Admits No Guilt; to Pay up to $275,000". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Perry v Atkinson". Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Eleanor Yang, "Naming of UCSD school sparks dispute; Sixth College should honor a noted Latino, some say", The San Diego Union-Tribune, April 18, 2005.

- ^ "La Jolla scholar-philanthropist Rita Atkinson dies at 91".

Further reading

edit- "Distinguished Scientific Contribution Awards for 1977," American Psychologist, January 1978, pp. 49–55.

- William J. McGill, "Richard C. Atkinson: President-Elect of AAAS," Science, Vol. 241, July 29, 1988, pp. 519–520.

- Richard C. Atkinson, "The Golden Fleece, Science Education, and US Science Policy," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 143, No, 3, September 1999, pp. 407–417.

- "Developing High-Technology Communities: San Diego," report by Innovation Associates, Inc., for the U.S. Small Business Administration, March 2000.

- Patricia A. Pelfrey, A Brief History of the University of California, Second Edition, (Center for Studies in Higher Education and University of California Press, 2004), pp. 78–89.

- David S. Saxon, "Foreword," The Pursuit of Knowledge: Speeches and Papers of Richard C. Atkinson, ed. Patricia A. Pelfrey (University of California Press, 2007), pp. ix-xi

- Patricia A. Pelfrey, The Entrepreneurial President: Richard Atkinson and the University of California, 1995-2003, (University of California Press, 2004).

External links

edit- Richard C. Atkinson biography Archived 2004-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- San Diego Reader account of Perry lawsuit

- President Richard C Atkinson's Home Page with more in-depth biographical information.

- Full text of Court of Appeal opinion - California Continuing Education of the Bar