The redwing (Turdus iliacus) is a bird in the thrush family, Turdidae, native to Europe and the Palearctic, slightly smaller than the related song thrush.

| Redwing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult T. i. iliacus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Turdidae |

| Genus: | Turdus |

| Species: | T. iliacus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Turdus iliacus | |

| |

Taxonomy and systematics

editThis species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae under its current scientific name.[2]

The English name derives from the bird's red underwing. It is not closely related to the red-winged blackbird, a North American species sometimes nicknamed "redwing", which is an icterid, not a thrush.[3] The binomial name derives from the Latin words turdus, "thrush", and ile "flank".[4]

About 65 species of medium to large thrushes are in the genus Turdus, characterised by rounded heads, longish, pointed wings, and usually melodious songs. Although two European thrushes, the song thrush and mistle thrush, are early offshoots from the Eurasian lineage of Turdus thrushes after they spread north from Africa, the redwing is descended from ancestors that had colonised the Caribbean islands from Africa and subsequently reached Europe from there.[5]

The redwing has two subspecies:[6][7][8]

- T. i. iliacus, the nominate subspecies described by Linnaeus, which breeds in mainland Eurasia.

- T. i. coburni described by Richard Bowdler Sharpe in 1901, which breeds in Iceland and the Faroe Islands and winters from western Scotland and Ireland south to northern Spain. It is darker overall, and marginally larger than the nominate form.

Description

editThe thrush is 20–24 cm long with a wingspan of 33–34.5 cm and a weight of 50–75 g. The sexes are similar, with plain brown backs and with dark brown spots on the white underparts. The most striking identification features are the red flanks and underwing, and the creamy white stripe above the eye.[6][7][8] Adults moult between June and September, which means that some start to replace their flight feathers while still feeding young.[9]

Song

editThe male has a varied short song, and a whistling flight call. Redwings show a distinct dialectic variation in song, having a considerable similarity in song patterns among birds within a local population.[10]

The Redwing song consists of a number of introductory elements of descending or ascending frequency. These elements may be of pure tonal quality, or of a more harsh quality (varying degrees of frequency modulations or "trills"). After the introductory elements, a fast and more complex song pattern often follows. It is the introductory elements which show a geographic variation. The boundaries of any given dialect may vary but in a rural and forested environment in Norway the average size of these dialect areas is around 41.5 km2.[10]

Distribution and habitat

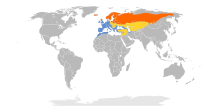

editThe redwing thrush breeds in northern regions of Europe and the Palearctic, from Iceland south to northernmost Scotland, and east through Scandinavia, the Baltic States, northern Poland and Belarus, and through most of Russia to about 165°E in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. In recent years it has expanded its range slightly, both in eastern Europe where it now breeds south into northern Ukraine, and in southern Greenland, where the Qaqortoq area was colonised in 1990–1991.[6][7][8]

It is often replaced by the related ring ouzel in areas of higher altitude.[11]

The thrush is migratory, wintering in western, central and southern Europe, north-west Africa, and south-west Asia east to northern Iran. Birds in some parts of the west of the breeding range (particularly south-western Norway) may be resident, not migrating at all, while those in the far east of the range migrate at least 6,500–7,000 km to reach their wintering grounds.[6][7][8]

There are multiple records of vagrants from the north-east coast of North America, as well as two sightings on the north-west coast (one in Washington in 2005, and one in Seward, Alaska in November 2011).[8]

Behaviour and ecology

editWhile migrating and wintering, redwing thrushes often form a loose flock. The size of the flock varies between 10 and at least 200 birds. They often feed together with fieldfares, common blackbirds and starlings. Sometimes, they will also feed alongside mistle thrushes, song thrushes, and ring ouzels.[6][7][8] Unlike the song thrush, the more nomadic redwing does not tend to return regularly to the same wintering areas.[12]

Migration occurs between autumn and early winter, and the birds often move at night. Oftentimes, they may make a "Tseep" contact call that can carry a long distance.[12]

Breeding

editThe redwing thrush breeds in conifer and birch forests, and the tundra. Redwings nest in shrubs or on the ground, laying four to six eggs in a neat nest. The eggs are typically 2.6 x 1.9 centimetres in size and weigh 4.6 grammes, of which 5% is shell,[4] and which hatch after 12–13 days. The chicks fledge 12–15 days after hatching, but the young remain dependent on their parents for another 14 days before they leave the nest.[6][7][8]

Feeding

editThe thrush is omnivorous, eating a wide range of insects and earthworms all year, supplemented by berries in autumn and winter, particularly of rowan Sorbus aucuparia and hawthorn Crataegus monogyna.[6][7][8]

Natural threats

editA Russian study of blood parasites showed that many of the fieldfares, redwings and song thrushes sampled carried haematozoans, particularly Haemoproteus and Trypanosoma.[13]

Status and conservation

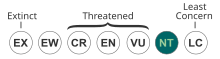

editThe redwing has an extensive range, estimated at 10 million square kilometres (3.8 million square miles), and an estimated population of 26 to 40 million individuals in Europe alone. The European population forms approximately 40% of the global population, thus the very preliminary estimate of the global population is 98 to 151 million individuals. The species is believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), and is therefore precautionarily uplisted to near threatened.[1] Numbers can be adversely affected by severe winters, which may cause heavy mortality, and cold wet summers, which reduce breeding success.[7]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2017). "Turdus iliacus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22708819A110990927. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T22708819A110990927.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 168.

T. alis subtus flavescentibus, rectricibus tribus lateralibus apice utrinque albis.

- ^ Jaramillo, Alvaro; Burke, Peter (1997). New World Blackbirds: The Icterids (Helm Identification Guides). Christopher Helm Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-7136-4333-1.

- ^ a b "Redwing Turdus iliacus [Linnaeus, 1766 ]". BTO Birdfacts. BTO. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ^ Reilly, John (2018). The Ascent of Birds. Pelagic Monographs. Exeter: Pelagic. pp. 221–225. ISBN 978-1-78427-169-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Snow, D. W. & Perrins, C. M. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic Concise Edition. OUP ISBN 0-19-854099-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Christie, D., eds. (2005). Handbook of the Birds of the World Vol. 10. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona ISBN 84-87334-72-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Clement, P., & Hathway, R. (2000). Thrushes Helm Identification Guides, London ISBN 0-7136-3940-7.

- ^ RSPB Handbook of British Birds (2014). UK ISBN 978-1-4729-0647-2

- ^ a b Bjerke, T. K., & Bjerke, T. H. (1981). Song dialects in the Redwing Turdus iliacus. Ornis Scandinavica, 40–50.

- ^ Evans G (1972). The Observer's Book of Birds' Eggs. London: Warne. p. 78. ISBN 0-7232-0060-2.

- ^ a b Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M., eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854099-X. p1215–1218

- ^ Palinauskas, Vaidas; Markovets, Mikhail Yu; Kosarev, Vladislav V; Efremov, Vladislav D; Sokolov Leonid V; Valkiûnas, Gediminas (2005). "Occurrence of avian haematozoa in Ekaterinburg and Irkutsk districts of Russia". Ekologija. 4: 8–12.