The red-tailed black shark (Epalzeorhynchos bicolor; syn. Labeo bicolor), also known as the redtail shark, red tailed shark, and redtail sharkminnow, is a species of tropical freshwater fish in the carp family, Cyprinidae. It is named after its shark-like appearance and movement, as well as its distinctive red tail.[2] Despite its name, it is more closely related to carp. It is endemic to streams and rivers in Thailand and is currently critically endangered.[1] However, it is common in aquaria, where it is prized for its deep black body, and vivid red orange tail. These are moderately sized tropical aquarium fish who are active benthic swimmers. They are omnivorous but are willing to scavenge if the opportunity arises. They are known for their activity as well as their temperament towards other fish. The red-tailed black sharks seen in the aquarium trade today are all captive bred.[1]

| Red-tailed black shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| A red-tailed black shark | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cypriniformes |

| Family: | Cyprinidae |

| Genus: | Epalzeorhynchos |

| Species: | E. bicolor

|

| Binomial name | |

| Epalzeorhynchos bicolor (H. M. Smith, 1931)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

editRed-tailed black sharks grow to be 6 inches (16 cm), but some specimens have reached 7–8 inches (18–20 cm). They have an black elongated body shape that is moderately compressed, and with the snout overhanging the mouth.[3] As juveniles they are all thin and streamlined. However, as they age their bodies becomes deeper in the midsection, which is most prominent in females.[2] Red-tailed black sharks have an inferior mouth that faces downwards, as well as two pairs of barbels around it.[3] Some specimens may have small black spots just above the lateral line that can be difficult to spot in life.[3]

Fins

editThe fins are all black except for the caudal fin, and occasionally the pectoral fins, which can be orange or red.[3] Its caudal fin is forked and colored a bright red that extends to the last few scales of the caudal peduncle.[3] The coloration of the tail can dim or fade when the individual is stressed, sick, or in poor water conditions.[2] The pointed lobes of the caudal fin are longer and larger than its head.[3] The dorsal fin is large and triangle shaped.[3] It is the largest fin on the fish with the longest ray being as long as the fish is deep.[3] The dorsal fin starts midbody but goes as far back as the peduncle, and occasionally having a white tip at the top.[2] The anal fin is also large and triangular but smaller than the dorsal fin. The rays of the anal fin almost reaches the base of the caudal fin.[3] The pelvic fins are triangular, are located ventrally and at the midbody, and are smaller than the anal and dorsal fins. The pectoral fins are shorter and placed lower on the body but not ventrally.[3] The pectoral fins are often more transparent than the other fins and can be either black, clear, or orange in color.

Sexual Dimorphism

editIt is difficult to discern sex of individual until around 15 months old.[2] Females tend to be larger and wider than males.[2] While males have brighter colors, slimmer bodies, and pointer dorsal fins.[2]

Rainbow Sharks

editRed-tailed black sharks have a similar appearance to the Rainbow shark. They both share the shark like appearance and movement as well as the red tail.[2] They are both common in aquaria and popular among freshwater aquarium hobbyists.[2] They eat the same diet patrolling the bottom for food and detritus to eat.[2] Both are largely active benthic swimmers who can be temperamental with tankmates and intolerant of their own species.[2] The rainbow shark is also a fellow member of the Cyprinidae family.[2] The main difference between the two is that all of the rainbow sharks’ fins are red, while only caudal and occasionally the pectoral fins of the red-tailed black sharks’ are red.

Distribution

editThis species is endemic to Thailand, and has been recorded in the lower Mae Khlong, Chao Phraya, and Bangpakong river basins.[1] It was described by Hugh M. Smith in 1931 as being "not uncommon in Borapet Swamp, Central Siam, and in the streams leading therefrom",[3] and as being found in the Chao Phraya River as far south as Bangkok.[1] A 1934 expedition reported catching a specimen in the Silom canal.[4] Red-tailed black sharks live in lowland streams, rivers, and creeks. They prefer areas with high flow, dense vegetation, large rocks and rocky or even sandy sediment.[2] However, from 1996 until 2011 it was believed to be extinct in the wild. In 2011 it was only known at a single location in the Chao Phraya basin, however it was believed to be strictly localized[5] and is thought to be extirpated across the rest of its range.[1] However, a single specimen was found in 2013 in a rocky dam around the mainstream of the Mae Khlong River in the Muang District of West Thailand.[6]

Biology

editOn average these fish live 5–8 years in captivity regardless of sex.[2] They are known egg layers, however breeding in home aquariums is practically impossible due to how aggressive and intolerant it is of its own kind.[2] Even so, breeding in captivity has been rare, but little information is known about how they spawn naturally even among enthusiasts. Little to nothing is known about what triggers breeding, what cues are used, competition, conditions, or how they choose mates. Captive breeding has been possible since at least 1987 through the injection of a mixture of hormones to induce spawning. However, they experience high mortality after spawning with rates as high as 80%.[7] The stress and complications of hormone induced spawning leaves many adults, and their spawn, vulnerable to disease such as Streptococcus iniae.[8]

Diet

editRed-tailed black sharks are omnivorous scavengers who are rarely picky eaters.[2] In the wild they eat insects, small crustaceans, worms, detritus, and plant matter.[2] They will also eat algae off rocks, plants, and décor similar to many popular sucker fish in aquariums. They will scavenge recently deceased fish and animals if given the chance. They generally patrol the bottom of the water column around rocks and plants searching for food.[2]

Behavior

editRed-tailed black sharks are fast active swimmers that patrol the bottom of the water column.[2] Their movement is reminiscent of sharks as they glide through the water with an oscillatory style of movement. They are known to be good jumpers and can jump out of most aquariums without a lid.[2] Red-tailed black sharks are territorial and aggressive to other fish, and especially intolerant of other red-tailed black sharks. They will establish their own territory and will harass and chase other fish within its territory, though having a larger space with plenty of hiding places can dissipate their aggression.[2] They may bully other fish that are smaller and slower to compete for food or space.[2] However, their behavior and treatment towards other fish does depend on the temperament of the individual. There are cases of red-tailed black sharks living peacefully with tankmates so long as their position and territory goes unchallenged. Because of this, they are usually labeled by hobbyists as semi-aggressive since their temperament can range from territorial to hot tempered depending on the individual.[2] They are solitary and will be aggressive and may even attack members of their own species who may compete for territory or food.[2] Juveniles however tend to be more timid than adults, and require more hiding places to feel comfortable.[2] Red tailed-black sharks are also nocturnal, being more active at night.[2]

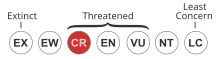

Conservation Status

editCurrently the Red Tailed Black Shark is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List.[1] The reason as to why the wild population has declined is not well known.[1] Intense overharvesting by the aquarium trade has historically been blamed for being responsible for the species’ decline.[1] However, this claim is still being debated with little documented evidence available to support this claim.[1] It could be argued that the aquarium trade saved the species from extinction, as breeding of red-tailed black sharks in countries such as Thailand and Sri Lanka has relieved pressure off of harvesting wild populations.[6] Presently, current wild populations are threatened by pollution from agricultural and domestic sources, as well as from habitat modification and degradation.[1] The construction of dams during the 1970s, the drainage of vast areas of swamp land, as well as additional infrastructure development such as road building likely caused great loss of habitat. Pollution runoff from farmlands and domestic sources may have caused changes in flow regimes and siltation to unsuitable levels.[1] Despite the many threats, the scope and severity that these fish face is currently unknown.[1]

Conservation Efforts

editThe Red Tailed Black Shark faces critical endangerment due to its disappearing rivers caused by climate change and human induced habitat destruction. As reported by the Journal of Applied Aquaculture, while most fish farmed now are for commercial purposes, artificial hormone induced spawning is extremely stressful and experiences high mortality afterwards.[8]

Scientists have been trying to reduce mortality rates by recognizing the species’ economic importance and vulnerability to diseases through vaccination of diseases such as Streptococcus iniae.[8] Studies of the efficacy of vaccinating red-tailed black shark during artificial spawning have been promising, showing a reduced mortality compared to those which were not vaccinated, and lowered mortality of spawned fish fry.[8] However, the fish that are bred in captivity may no longer be genetically suitable for release into the wild via hatchery raised reintroduction.[1] The ICUN has recommended that an ex-situ conservation breeding program be established in captivity with the specific purpose of conservation and reintroduction to wild populations.[1] The ICUN also recommends that further research is needed to understand the population trends, life history, ecology, threats, and actions for conservation for the red-tailed black shark.[1]

Aquarium Trade

editThese fish are relatively common to find in pet shops or on online aquarium stores, usually costing between $3 - $7 per fish.[2] It is very popular in the trade, in 1987 Thailand exported as much as 5 million a year.[7] An analysis of the most valuable ornamental fish imported into the United States in October 1992 showed that ‘Labeo bicolor’ was the 20th most popular and valuable fish imported that year, making up 1% of total ornamental fish sales in the country.[9] All of the ones that are sold today are captive bred, and not wild caught.

Aquarium Requirements

editIt is recommended that they are given a medium to large sized tank of 30 gallons or more.[2] Preferably an elongated tank as they are active bottom swimmers and need more space laterally to explore than they need depth. Too small a tank can promote stress, aggression and even disease.[2] A weighted lid is also needed to prevent jumping. They do best in fast flow with plenty of hiding spots and caves to explore and exercise.[2] As they are tropical fish, water temperature should be between 72°-80° Fahrenheit or between 22°-26° Celsius. The pH should be close to neutral. They also do best with an air stone to produce lots of dissolved oxygen in the water.[2]

Tankmates

editWhile these fish can be temperamental it is possible to keep tankmates with them. Faster moving fish such as danios and other minnows are fast enough to stay out of red-tailed black sharks’ way.[2] Other larger aggressive fish such as cichlids, some gourami, and certain barbs can match their aggressiveness and keep the shark in line or hold their own.[2] Tetras are often common tank mates, though some red-tailed black sharks do bully even these peaceful fish.[2] However, slow moving, timid, long finned, and smaller fish are often victims of this fish's short temper. Smaller angelfish, fancy guppies, and betta fish are poor choice of tank mates for this cyprinid.[2] Other bottom feeders such as Corydora catfish or loaches are not recommended by some as they occupy and compete for the same territory and food.[2] Invertebrates such as shrimp should not be added to a tank with this fish as they will be eaten.[2]

Footnotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Vidthayanon, C. (2011). "Epalzeorhynchos bicolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T7807A12852157. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T7807A12852157.en.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak "Red Tail Shark: Expert Care Guide for Aquarists". Fishkeeping World. 1 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Smith, Hugh W. (1931). "Descriptions of new genera and species of Siamese fishes". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 79 (2873): 1–48. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.79-2873.1.

- ^ Fowler, Henry W. (1934). "Zoological Results of the Third De Schauensee Siamese Expedition, Part V: Additional Fishes". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 86: 335–352. JSTOR 4064154.

- ^ Kulabtong, Sitthi & Suksri, Siriwan & Nonpayom, Chirachai & Soonthornkit, Yananan. (2014). "Rediscovery of the critically endangered cyprinid fish Epalzeorhynchos bicolor (Smith, 1931) from West Thailand (Cypriniformes, Cyprinidae)" (PDF). Biodiversity Journal. 5: 371–373.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kottelat, Maurice and Whitten, Tony (30 September 1996). "Freshwater biodiversity in Asia". World Bank Technical Papers. doi:10.1596/0-8213-3808-0.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Meenakarn, Wanpen, and Ongsuwan, Nongnuch (1 Jan 1987). "Induced Spawning on Red Tailed Shark Epalzeorhynchos Bicolor (Smith)". International System for Agricultural Science and Technology (AGRIS).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Russo, Riccardo, and Yanong, Roy P. (26 Feb 2009). "Efficacy of vaccination against streptococcus iniae during artificial spawning of the red-tail black shark (epalzeorhynchos bicolor, Fam. Cyprinidae)". Journal of Applied Aquaculture. 21 (1): 10–20. doi:10.1080/10454430802694454.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chapman, Frank A., Fritz-Coy, Sharon and Thunberg, Eric and Rodrick, Jeffrey T., Adams, Charles M., Andre, Michel (1 Jan 1994). "An Analysis of the United States of America International Trade in Ornamental Fish". NOAA Institutional repository.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

edit- da Silva Henriques, L. G. (2016). Induction of gonadal growth/maturation in the ornamental fishes Epalzeorhynchos bicolor and Carassius auratus and stereological validation in C. auratus of histological grading systems for assessing the ovary and testis statuses.

- "Integrated Taxonomic Information System - Report." ITIS, www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=639588#null. Accessed 15 Oct. 2024.

- "Red Tailed Shark." Keeping Tropical Fish, 21 May 2015, www.keepingtropicalfish.co.uk/fish-database/red-tailed-shark/.