This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (December 2015) |

In physics, the Rabi cycle (or Rabi flop) is the cyclic behaviour of a two-level quantum system in the presence of an oscillatory driving field. A great variety of physical processes belonging to the areas of quantum computing, condensed matter, atomic and molecular physics, and nuclear and particle physics can be conveniently studied in terms of two-level quantum mechanical systems, and exhibit Rabi flopping when coupled to an optical driving field. The effect is important in quantum optics, magnetic resonance and quantum computing, and is named after Isidor Isaac Rabi.

A two-level system is one that has two possible energy levels. These two levels are a ground state with lower energy and an excited state with higher energy. If the energy levels are not degenerate (i.e. not having equal energies), the system can absorb a quantum of energy and transition from the ground state to the "excited" state. When an atom (or some other two-level system) is illuminated by a coherent beam of photons, it will cyclically absorb photons and re-emit them by stimulated emission. One such cycle is called a Rabi cycle, and the inverse of its duration is the Rabi frequency of the system. The effect can be modeled using the Jaynes–Cummings model and the Bloch vector formalism.

Mathematical description

editRabi flopping refers to the spin flipping within a quantum system containing a spin-1/2 particle and an oscillating magnetic field. We split the magnetic field into a constant 'environment' field, and the oscillating part, so that our field looks like where and are the strengths of the environment and the oscillating fields respectively, and is the frequency at which the oscillating field oscillates. We can then write a Hamiltonian describing this field, yielding where , , and are the spin operators. The frequency is known as the Rabi frequency. We can substitute in their matrix forms to find the matrix representing the Hamiltonian: where we have used . This Hamiltonian is a function of time, meaning we cannot use the standard prescription of Schrödinger time evolution in quantum mechanics, where the time evolution operator is , because this formula assume that the Hamiltonian is constant with respect to time.

The main strategy in solving this problem is to transform the Hamiltonian so that the time independence is gone, solve the problem in this transformed frame, and then transform the results back to normal. This can be done by shifting the reference frame that we work in to match the rotating magnetic field. If we rotate along with the magnetic field, then from our point of view, the magnetic field is not rotating and appears constant. Therefore, in the rotating reference frame, both the magnetic field and the Hamiltonian are constant with respect to time.

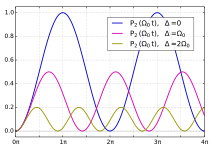

We denote our spin-1/2 particle state to be in the stationary reference frame, where and are spin up and spin down states respectively, and . We can transform this state to the rotating reference frame by using a rotation operator which rotates the state counterclockwise around the positive z-axis in state space, which may be visualized as a Bloch sphere. At a time and a frequency , the magnetic field will have precessed around by an angle . To transform into the rotating reference frame, note that the stationary x and y-axes rotate clockwise from the point of view of the rotating reference frame. Because the operator rotates counterclockwise, we must negate the angle to produce the correct state in the rotating reference frame. Thus, the state becomes We may rewrite the amplitudes so that The time dependent Schrödinger equation in the stationary reference frame is Expanding this using the matrix forms of the Hamiltonian and the state yields Applying the matrix and separating the components of the vector allows us to write two coupled differential equations as follows To transform this into the rotating reference frame, we may use the fact that and to write the following: where . Now define We now write these two new coupled differential equations back into the form of the Schrödinger equation: In some sense, this is a transformed Schrödinger equation in the rotating reference frame. Crucially, the Hamiltonian does not vary with respect to time, meaning in this reference frame, we can use the familiar solution to Schrödinger time evolution: This transformed problem is equivalent to that of Larmor precession of a spin state, so we have solved the essence of Rabi flopping. The probability that a particle starting in the spin up state flips to the spin down state can be stated as where is the generalized Rabi Frequency. Something important to notice is that will not reach 1 unless . In other words, the frequency of the rotating magnetic field must match the environmental field's Larmor frequency in order for the spin to fully flip; they must achieve resonance. Note that when resonance is achieved, .

To transform the solved state back to the stationary reference frame, we reuse the rotation operator with the opposite angle , thus yielding a full solution to the problem.

Applications

editThe Rabi effect is important in quantum optics, magnetic resonance and quantum computing.

Quantum optics

editRabi flopping may be used to describe a two-level atom with an excited state and a ground state in an electromagnetic field with frequency tuned to the excitation energy. Using the spin-flipping formula but applying it to this system yields

where is the Rabi frequency.

Quantum computing

editAny two-state quantum system can be used to model a qubit. Rabi flopping provides a physical way to allow for spin flips in a qubit system. At resonance, the transition probability is given by To go from state to state it is sufficient to adjust the time during which the rotating field acts such that or . This is called a pulse. If a time intermediate between 0 and is chosen, we obtain a superposition of and . In particular for , we have a pulse, which acts as: The equations are essentially identical in the case of a two level atom in the field of a laser when the generally well satisfied rotating wave approximation is made, where is the energy difference between the two atomic levels, is the frequency of laser wave and Rabi frequency is proportional to the product of the transition electric dipole moment of atom and electric field of the laser wave that is . On a quantum computer, these oscillations are obtained by exposing qubits to periodic electric or magnetic fields during suitably adjusted time intervals.[1]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ A Short Introduction to Quantum Information and Quantum Computation by Michel Le Bellac, ISBN 978-0521860567

- Quantum Mechanics Volume 1 by C. Cohen-Tannoudji, Bernard Diu, Frank Laloe, ISBN 9780471164333

- A Short Introduction to Quantum Information and Quantum Computation by Michel Le Bellac, ISBN 978-0521860567

- The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Volume III

- Modern Approach To Quantum Mechanics by John S Townsend, ISBN 9788130913148