Quezon City (UK: /ˈkeɪzɒn/, US: /ˈkeɪsɒn, -sɔːn, -soʊn/;[9][10][11][12] Filipino: Lungsod Quezon [luŋˈsod ˈkɛson] ⓘ), also known as the City of Quezon and Q.C. (read and pronounced in Filipino as Kyusi),[13][14][15] is the most populous city in the Philippines. It is also the richest city in the Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 2,960,048 people. It was founded on October 12, 1939, and was named after Manuel L. Quezon, the second president of the Philippines.

Quezon City

Lungsod Quezon | |

|---|---|

Banawe Street Araneta Cubao Bus Terminal | |

|

| |

| Nickname: | |

| Anthem: Awit ng Lungsod Quezon (Anthem of Quezon City) | |

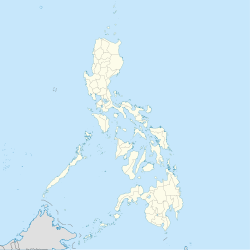

Map of Metro Manila with Quezon City highlighted | |

Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 14°39′00″N 121°02′51″E / 14.65°N 121.0475°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | National Capital Region |

| Province | none |

| Districts | 1st to 6th districts |

| Incorporated (city) | October 12, 1939 |

| Highly urbanized city | December 22, 1979 |

| Named for | Manuel L. Quezon |

| Barangays | 142 (see Barangays) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Panlungsod |

| • Mayor | Joy Belmonte (SBP) |

| • Vice Mayor | Gian Sotto (SBP) |

| • Representatives | |

| • Council | Councilors |

| • Electorate | 1,403,895 voters (2022) |

| Area | |

• Total | 171.71 km2 (66.30 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 67 m (220 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 796 m (2,612 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −2 m (−7 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[6] | |

• Total | 2,960,048 |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 17,000/km2 (45,000/sq mi) |

| • Households | 738,724 |

| Demonym(s) | Taga-QC QCitizen |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | 1st city income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 0.7 |

| • Revenue | ₱ 26,462 million (2022) |

| • Assets | ₱ 441,279 million (2022) |

| • Expenditure | ₱ 25,352 million (2022) |

| • Liabilities | ₱ 27,723 million (2022) |

| Service provider | |

| • Electricity | Manila Electric Company (Meralco) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | 1100 to 1138[8] |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)2 |

| Native languages | Tagalog |

| Major religions | Catholic |

| Catholic diocese | Roman Catholic Diocese of Cubao, Roman Catholic Diocese of Novaliches |

| Patron saint | Our Lady of La Naval de Manila |

| Website | quezoncity |

The city was intended to be the national capital of the Philippines that would replace Manila, as the latter was suffering from overcrowding, lack of housing, poor sanitation, and traffic congestion. To create Quezon City, several barrios were carved out from the towns of Caloocan, Marikina, San Juan and Pasig, in addition to the eight vast estates the Philippine government purchased for this purpose. It was officially proclaimed the national capital on October 12, 1949, and several government departments and institutions moved out of Manila and settled into the new capital city. This necessitated the expansion of the city northward, carving out Novaliches from Caloocan which divided it into two non-contiguous parts. Several barrios were also taken from San Mateo and parts of Montalban. However, on June 24, 1976, Presidential Decree No. 940 was enacted, which reverted national capital status to Manila while the whole of Metro Manila was designated as the seat of government.[16][17] The city was also chosen as the regional center of Southern Tagalog, which was created in 1965, along with the provinces of Quezon and Aurora, the birthplace of Manuel L. Quezon; however, its status of regional center became ineffective when the region was divided into Calabarzon and Mimaropa, through the effect of Executive Order No. 103 in May 2002 under the presidency of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, and Aurora was transferred to the authority of Central Luzon, with Southern Tagalog limited to being a cultural-geographic region.[18]

Quezon City is known for its culture, entertainment industry and media, and is aptly called the "City of Stars". Major broadcasting networks have their headquarters and studios in the city. It is also known for its commerce, education, research, technology, politics, tourism, art and sports. Several national government branches including the Batasang Pambansa Complex, the seat of House of Representatives of the Philippines, call the city home.

Quezon City is a planned city. It covers a total area of 161.11 square kilometers (62.20 sq mi),[5] making it the largest city in Metro Manila/NCR in terms of land area. It is politically subdivided into Six Congressional Districts, which represent the city in the Lower House of the Congress of the Philippines. The city has 142 barangays under the City Government. National government departments and agencies are mostly situated in the first National Government Center (NGC) in Diliman. and the second National Government Center in Batasan Hills, where the Lower House of the Philippine Congress is located. Most of the city's northern part lies at the foothills of the Sierra Madre mountain range, including the La Mesa Watershed Reservation, the largest watershed in Metro Manila and a designated protected area.

According to its 2023 estimated census, Quezon City had 3.1 million people in its boundaries, and 93.8 billion dollars in its GDP, and it is the only planned city in the National Capital Region of the Philippines.

History

editCommonwealth era

editInitial plans for a new capital city

editBefore the creation of Quezon City, the land on where it would eventually rise was part of several towns such as Caloocan, Mariquina (Marikina), Montalban (renamed as Rodriguez), Pasig, San Mateo, and San Juan del Monte (renamed as San Juan), all under Manila province and, beginning in 1901, Rizal province.

In the 1930s, Manila's urban problems were apparent and problematic.[19] It lacked public housing, where thousands of the city's residents lived in congested informal settler communities, especially in the central districts of Binondo, Intramuros, Quiapo, San Nicolas and Tondo.[19] There were also problems with sanitation and traffic congestion.[19] The rise of slums in Manila gave rise to the development of its suburbs outside the city limits in the municipalities of Pasay, San Felipe Neri (renamed as Mandaluyong), San Francisco del Monte, Makati, and San Juan del Monte.[19] These towns became favorable to the upper and middle-class who wanted to escape the congested city but had economic links to it.[19]

President Manuel L. Quezon, aware of the problems besetting Manila, initiated housing projects called Barrio Obrero (Worker's Community).[19] These communities were established in various places in Manila such as Avenida Rizal, Sta. Cruz and Barrio Vitas, Tondo.[19] However, the project failed miserably and these communities became slum areas.[19]

Alejandro Roces Sr., a prominent Filipino author, was said to be influential in Quezon's vision to establish a new city.[19] Quezon dreamed of a city where the common people could live and thrive.[19] Roces suggested that a sizeable tract of land be purchased for this purpose.[19] However, the government had no available fund except for ₱3 million in the hands of the National Development Company (NDC).[19]

In order to make Quezon's dream a reality and to mobilize funds for the land purchase, the People's Homesite Corporation (PHC) was created on October 14, 1938, as a subsidiary of NDC, with an initial capital of ₱2 million.[19] Roces was the chairman of the Board of PHC, and they immediately acquired the vast Diliman Estate of the Tuason family at a cost of 5 centavos per square meter.[19] PHC conducted topographical and subdivision surveys, and then subdivided the lots and sold them to the target buyers at an affordable price.[19] Its target users and beneficiaries were Manila's working class,[20] who were suffering from a shortage of affordable and decent housing in the capital.[19] The service of the Metropolitan Waterworks system was extended to site.[19] The Bureau of Public Works, then under Secretary Vicente Fragante, constructed the streets and highways within the property.[19] Quezon also tapped Architect Juan M. Arellano to draft a design of the city.[19] Eight vast estates were acquired in order to create Quezon City: Diliman Estate, 1,573.22 hectares (15.7322 km2), Santa Mesa Estate, 861.79 hectares (8.6179 km2), Mandaluyong Estate, 781.36 hectares (7.8136 km2), Magdalena Estate, 764.48 hectares (7.6448 km2), Piedad Estate, 743.84 hectares (7.4384 km2), Maysilo Estate, 266.73 hectares (2.6673 km2) and the San Francisco Del Monte Estate, 257.54 hectares (2.5754 km2).[19] Quezon's goal was to create a place for the working class, coinciding with the planned transfer of the University of the Philippines campus in Manila to a more suitable location, which became another precedent for the creation of Quezon City.[19]

As early as 1928, the University of the Philippines (UP) had planned to expand by adding more academic units and constructing new buildings.[19] The university experienced increase in enrollment and its planned expansion was hampered by its small campus in Manila.[21] The revised Burnham Plan of Manila envisioned the new campus to be located just outside Manila's city limits at 'the heights behind Manila'.[19] The UP Board of Regents informed Quezon of their desire to relocate the campus and he was supportive of the idea.[19] Furthermore, he wanted the facilities in the Manila campus to be used for government purposes.[19] In 1939, Quezon urged the National Assembly to enact UP's relocation and on June 8, 1939, Commonwealth Act No. 442 was passed, enacting the transfer of UP outside of Manila.[22] A portion of Mariquina Estate, which was adjacent to Magdalena Estate, was chosen as the new site with an approximate area of 600 hectares.[19] Additional land from the Diliman Estate was also added as part of the new university campus.[19]

Creation of Quezon City

editWith the development of the People's Homesite Corporation housing in the Diliman Estate and the creation of the new UP Campus, the creation of Quezon City was justified.[19] On October 12, 1939, Commonwealth Act No. 502, also known as the Charter of Quezon City, was passed by the National Assembly, which created Quezon City.[23] Surprisingly, Quezon allowed the bill to lapse into law because he did not sign it.[19] The city was originally to be known as Balintawak City according to the first bill filed by Assemblyman Ramon P. Mitra Sr. from Mountain Province, but Assemblymen Narciso Ramos and Eugenio Perez, both from Pangasinan, amended and successfully lobbied the assembly to name the city after the President in honor of his role in the creation of this new city.[24][25][19] The creation of Quezon City halted the full implementation of the Burnham Plan of Manila and funds were diverted for the establishment of the new capital.

Several barangays from different towns were carved out to correspond to the estates that PHC bought for the creation of Quezon City.[19] The new city had an area of 7,355 hectares (73.55 km2), and the barrios and sitios that were taken for its creation were the following: Bagubantay (Bago Bantay), Balingasa, Balintauac (Balintawak), Kaingin, Kangkong, Loma (La Loma), Malamig, Matalahib, Masambong, San Isidro, San Jose, Santol and Tatalon, were taken from Caloocan;[26] Cubao, Diliman, Kamuning, New Manila, and San Francisco del Monte were taken from San Juan; Balara, Barranca (Barangka), Jesus de la Peña, Krus na Ligas, Tañong and the site of the new UP Campus were taken from Marikina; and, the barrios and sitios of Libis, and Ogong (Ugong Norte) from Pasig.[19] Commonwealth Act No. 659, enacted on June 21, 1941, changed the city's boundaries.[27] Under this law, the area of Wack Wack Golf and Country Club were to be reverted to Mandaluyong, and the barrios of lower Barranca and Jesus de la Peña were reverted to Marikina. However, Camp Crame was taken out of San Juan and was given to Quezon City.[19][27]

1939, the year the city was established, recorded a population of 39,103 people. The city in its early days was predominantly rural, but Quezon asked American Architect William Parsons to craft a master plan for the newly created city.[19] Parsons was the one who advised Quezon to locate the National Government Center in Diliman instead of Wallace Field (now Rizal Park), due to the possibility of naval bombardment from Manila Bay.[19] Unfortunately, he died in December 1939 and his partner Harry T. Frost took over and become the lead planner.[19] Frost arrived in the Philippines on May 1, 1940, and became the architectural adviser of the Philippine Commonwealth government.[19] Together with Juan M. Arellano, Alpheus D. Williams, and Welton Becket, they created the Master Plan for Quezon City which was approved by the Philippine government in 1941.[19] The Frost Plan featured wide avenues, large open spaces and roundabouts at major intersections.[19] The plan for major thoroughfares made by Louis Croft for the Greater Manila Area served as the backbone for the Plan of Quezon City.[19] The center of the city was a 400-hectare quadrangle formed by four avenues — North, West, South and East — which was designed to be the location of the National Government of the Philippines.[28] At the northeast corner of the Quadrangle was a large roundabout, a 25-hectare (62-acre) elliptical site, were the proposed Capitol Building is envisioned to rise.[19]

To make the city accessible, Quezon ordered Luzon Bus Lines to ply from Kamuning towards Tutuban in Divisoria, Manila to provide transport for the city's residents. However, the fare was not affordable to minimum wage earners. Because of the city's unaffordable housing prices and lack of transportation for low-income earners, the goal of creating mass housing for the working class was not met. Instead, those who opted to live in Quezon City consisted of middle-class households such as those in Kamuning, whose residents petitioned to rename it from Barrio Obrero (Worker's Community) to Kamuning (a type of tree that grows abundantly in the area) because its residents were not Obreros (Workers).[19]

Japanese occupation era

editThe Philippine Exposition in 1941 was held on the newly established Quezon City, but participants were limited to locals because of the increasing turbulence at the beginning of the Second World War.[19] Eventually, parts of Manila were bombed by the Japanese Imperial Forces in December 1941, bringing the war to the Philippines. On January 1, 1942, President Quezon issued Executive Order No. 400 as an emergency measure to form the City of Greater Manila, with Jorge B. Vargas as its designated mayor. It merged the city with Manila and the towns of Caloocan, Makati, Mandaluyong, Parañaque, Pasay, and San Juan. The mayors of these towns and cities served as the assistant mayor of their respective localities and were under the mayor of Greater Manila.[29][30] The City of Greater Manila was the basis for the formation of Metro Manila in 1975.

After Imperial Japanese forces conquered the Philippines during the Pacific War, the City of Greater Manila was reorganized in 1942 into twelve districts, two of which were formed by dividing Quezon City: Balintawak which consisted of San Francisco del Monte, Galas, La Loma, New Manila, Santa Mesa Estate, the Wack Wack Golf and Country Club, and the present-day Greenhills, San Juan; and Diliman which was composed of Diliman proper, Cubao, the University District, and the present-day eastern portion of Marikina.[31] In the same year, the patients of Quezon Institute were relocated to the San Juan de Dios Hospital in Intramuros and the Japanese military used the facility for its own sick and wounded. The Japanese renamed some streets, most notably South Avenue which became Timog Avenue. In 1944, when the Americans returned to Luzon, they gave numerical designations to some roads such as Route 54, which is now E. de los Santos Avenue. In 1945, the City of Greater Manila was dissolved by President Sergio Osmeña, thus separating the cities and towns that were consolidated and regaining their pre-war status.[32] The area which formed the city was then governed by the Philippine Executive Commission. In the same year, combined Filipino and American troops under the United States Army, Philippine Commonwealth Army, and Philippine Constabulary, with help from recognized guerrilla units, liberated and recaptured Quezon City in a few months, expelling Imperial Japanese forces. Heavy fighting occurred in Novaliches, which at that time was within Caloocan, and New Manila which had been fortified. Smaller actions were fought at Barrio Talipapa and the University District.

The postwar and independence era

editExisting territorial boundaries

Detached by Commonwealth Act No. 502 (1939)

Novaliches area; detached by Republic Act No. 392 (1949)

On July 17, 1948, President Elpidio Quirino signed Republic Act No. 333 into law, making Quezon City the capital of the Philippines.[33] The Act created the Capital City Planning Commission, which was tasked to develop and implement a masterplan for the city.[5] As the capital, the city was expanded northwards, and the barrios of Baesa, Bagbag, Banlat, Kabuyao, Novaliches Proper (Bayan/Poblacion), Pasong Putik, Pasong Tamo, Pugad Lawin, San Bartolome, and Talipapa in Novaliches were ceded from Caloocan. This territorial change caused the division of Caloocan into two non-contiguous parts.[5] Quezon City was formally inaugurated as the capital on October 12, 1949. President Quirino laid the cornerstone on the proposed Capitol Building at Constitution Hills.[5]

On June 16, 1950, the Quezon City Charter was revised by Republic Act No. 537, changing the city's boundaries to an area of 153.59 km2 (59 sq mi).[34] Exactly six years later, on June 16, 1956, more revisions to the city's territory were made by Republic Act No. 1575, which defined its area as 151.06 km2 (58 sq mi).[35] However, according to the 1995 GIS graphical plot, the city's total area is 161.11 km2 (62.20 sq mi), making it the largest Local Government Unit in Metro Manila in terms of land area.[36][5]

The Marcos administration era

editThe turn of the decade from the 1960s to the 1970s brought an era of change and tumult throughout the Philippines, with many of the historically significant events of the era taking place in or involving people and groups from Quezon City.

Before Martial Law

editWhen Ferdinand Marcos' economic policy of using foreign loans to fund government projects during his second term resulted in the 1969 balance of payments crisis,[37][38][39] students from Quezon City-based universities, notably the University of the Philippines Diliman and Ateneo de Manila University were among the first to call for change, ranging from moderate policy reforms to radical changes in form of government.[40][41]

Students from these Quezon City schools, representing a spectrum of positions, were thus at the front lines of the major protests of the first three months of 1970 – what would later be called the "First Quarter Storm." A year later in 1971, this was followed up by the Diliman Commune, in which the students, faculty, and residents of UP Diliman initially planned to protest an impending oil price hike, but because of violent attempts to disperse them, also later demanded that Marcos' military pledge not to assault the campus in the future.[41]

After the Martial Law proclamation

editMarcos' declaration of martial law in September 1972 saw the immediate shutdown of all media not approved by Marcos, including Quezon City media outlets such as GMA Channel 7 and ABS-CBN Channel 2. At the same time, it saw the arrest of many students, journalists, academics, and politicians who were considered political threats to Marcos, many of them residents of Quezon City. By the morning after Marcos' televised announcement of the proclamation, about 400 of these arrestees were gathered in Camp Crame on the southwestern reaches of Quezon City, destined to be among the first of thousands of political detainees under the Marcos dictatorship.[41]

Camp Crame would be the site of many of the human rights abuses of the Marcos dictatorship, with one of the first being the murder of student journalist Liliosa Hilao in Camp Crame.[42] Among the prominent cases of abuse suffered specifically by Quezon City residents were the cases of Primitivo Mijares and his sixteen-year-old son Boyet Mijares, who lived in Project 6 at the time of their deaths;[43] Roman Catholic Diocese of Cubao social worker Purificacion Pedro who was murdered by a soldier at her hospital room in Bataan;[44] 23-year old Kamias resident and student activist Roland Jan Quimpo who became a desaparecido;[45] and Cubao-based tailor Rolando "Lando" Federis who was abducted by armed men in Lucena City while accompanying a group of activists to Bicol, tortured, and then killed.[46] In addition, a large number of student activists who were caught, detained, tortured, sexually abused, killed, and disappeared by the regime had been studying in the various universities and colleges in Quezon City.[41]

One of the key moments that led to the eventual demise of the Marcos dictatorship was the 1974 Sacred Heart Novitiate raid, in which a Catholic seminary in Novaliches was raided on the suspicion that communist leaders were hiding there. The arrest of Fr. Benigno Mayo who was the head of the Jesuit order in the Philippines at the time, and Fr. Jose Blanco alongside 21 members of the youth group called Student Catholic Action (SCA), helped convince "the formerly neutral Philippine middle class" that Marcos' powers had grown too great.[47][48]

As international pressure forced Marcos to start restoring civil rights, other key moments in Philippine history took place in Quezon City. Journalist Joe Burgos established the Quezon City-based WE Forum newspaper in 1977 and in it published a story by Colonel Bonifacio Gillego in November 1982 which discredited many of the Marcos medals.[49] Media coverage of the September 1984 Welcome Rotonda protest dispersal showed how opposition figures including 80-year-old former Senator Lorenzo Tañada and 71-year old Manila Times founder Chino Roces were waterhosed despite their frailty and how student leader Fidel Nemenzo (later Chancellor of the University of the Philippines Diliman) was shot nearly to death.

Most significantly, the August 1983 funeral of assassinated opposition leader of Ninoy Aquino began at the Aquino family household in Times Street, West Triangle, Quezon City, and continued to the funeral mass at Santo Domingo Church in Santa Mesa Heights before the final interment at the Manila Memorial Park. The procession took from 9:00 AM until 9:00 PM to finish as two million people joined the crowd. The experience galvanized many of the Philippines into resisting the dictatorship, with protests against Marcos snowballing until they happened nearly every week, and until Marcos was ousted by the People Power revolution.[50]

Physical and administrative changes during the Marcos administration

editIn terms of administrative changes during this period, the region of Metro Manila was created as an integrated unit with the enactment of Presidential Decree No. 824 on November 7, 1975. The region encompassed four cities and thirteen adjoining towns, as a separate regional unit of government.[51] A year later, on June 24, 1976, Manila was reinstated by President Marcos as the capital of the Philippines for its historical significance as the seat of government since the Spanish Period. Presidential Decree No. 940 states that Manila has always been to the Filipino people and in the eyes of the world, the premier city of the Philippines being the center of trade, commerce, education and culture.[17] Concurrent with the reinstatement of Manila as the capital, Ferdinand Marcos designated his wife, Imelda Marcos, as the first governor of Metro Manila, who started the construction of massive government edifices with architectural significance as she re-branded Manila as the "City of Man".[52]

On March 31, 1978, President Marcos ordered the transfer of the remains of President Quezon from Manila North Cemetery to the newly completed Quezon Memorial Shrine.[53][54] It now houses the mausoleum where President Quezon and his wife Aurora Aragon Quezon are interred. It also contains a museum dedicated to President Quezon and his life.

EDSA people power

editIn 1986, the nonviolent People Power Revolution, led by Corazon Aquino and Cardinal Jaime Sin, ousted Marcos from power. Thousands of people flocked EDSA between Camp Crame and Camp Aguinaldo in a series of popular demonstrations and civil resistance against the Marcos government that occurred between February 22 and 25, 1986.[55]

Commemorative monuments

editAll of the three major monuments commemorating the Martial Law era are located in Quezon City.[56] The People Power Monument and the EDSA Shrine were built in the city to commemorate the event, with the latter being a symbol of the role that the Catholic Church played in the restoration of democracy in the Philippines. The Bantayog ng mga Bayani was constructed along Quezon Avenue to honor the heroes and martyrs that struggled under the 20-year Marcos regime. The Wall of Remembrance at the Bantayog honors prominent figures during the martial law era.[57][58]

Contemporary

editOn February 23, 1998, Republic Act. No. 8535 was signed by President Fidel Ramos, which paved the way for the creation of the City of Novaliches by carving out the 15 northernmost barangays of Quezon City.[59][60][61] The voting process only includes the affected barangays, but then-city mayor of the town Ismael "Mel" Mathay Jr. lobbied to include the whole city. He also campaigned against the secession of Novaliches. In the succeeding plebiscite that was held on October 23, 1999, an overwhelming majority of Quezon City residents rejected the secession of Novaliches. Mathay was succeeded by Feliciano Belmonte Jr., who served as the city mayor from 2001 to 2010.

On May 1, 2001, numerous residents of Barangay Holy Spirit who have been protesting against the arrest of former president Joseph Estrada marched from EDSA Shrine to Malacañang and participated in the May 1 riots against President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.[62]

In the 2010 local elections, actor Herbert "Bistek" Bautista, who served as Vice mayor during Belmonte's term, was elected as the city mayor. During his term, the Quezon City Pride Council was established. It was the first LGBT council in the Philippines.[63] He also initiated numerous socialized housing projects called "Bistekville". Bautista was succeeded by Maria Josefina "Joy" Belmonte in 2019, who has served as the Vice Mayor under his term and the daughter of former Quezon City mayor Feliciano Belmonte Jr. She was then reelected as City Mayor in 2022, after which the Quezon City People's Council was established. Under the Participation, Accountability and Transparency Ordinance, the council would serve as an umbrella for about 2,232 civil society organizations accredited by the city government as a means for more civic participation and as for the council to be the “eyes, ears and voice” of the city residents in the city government.[64]

Beginning March 15, 2020, Quezon City was placed under community quarantine, which were introduced due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the country. The strictest quarantine was the enhanced community quarantine in 2020 and 2021, in response to the then-ongoing pandemic in the city, which has infected more than 100,000 of the city's residents with more than 1,200 deaths. The quarantine was later downgraded to the alert level system (ALS) in 2021 until the state of public health emergency was lifted by President Bongbong Marcos on July 21, 2023.[65]

No-contact apprehension policy

editOn July 1, 2022, the Quezon City government began fully implementing its No Contact Apprehension Policy on several major roads in the city. As a result, closed-circuit television cameras were installed on some intersections along Quirino Highway, E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue, Aurora Boulevard, West Avenue, East Avenue, Kamias Road, and P. Tuazon Boulevard. Motorists that violate traffic policies would be sent a notice of violation by mail. This notice of violation is expected to be delivered within 14 days for city residents while non-residents are expected to receive their notices beyond the regular 14 days. Any traffic violations registered in the system can be checked from a dedicated website and its fines can be paid online.[66]

However, the policy has been criticized by motorists due to several intersections that have unclear directives on the proper way to navigate them correctly. In particular, several motorists complained on social media after they were ticketed for turning "in the wrong lane" at the intersection of E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue and Gilmore Avenue, where the rightmost lane is cut in half by Quezon City's bike lane network.[67]

Geography

editThe geography of Quezon City is characterized by undulating terrain. The city is within the catchment area of five river systems – Marikina, Pasig, San Juan, Tullahan and Meycauayan – along with their creeks and tributaries with a total length of almost 200 km (120 mi).[68] The city has an area of 161.11 km2 (62.20 sq mi), according to the 1995 GIS graphical plot, making it the largest Local Government Unit (LGU) in Metro Manila in terms of land area.[36] Since its creation in 1939, the city's boundary were revised four times; the final revision was made thru Republic Act No. 1575, which placed the city's territory at 151.06 square kilometers (58.32 sq mi).[5] Meanwhile, the Philippine Statistics Authority placed the city's land area at 171.71 square kilometers (66.30 sq mi), based on data provided by the Land Management Bureau. According to the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology and Geoscience Australia on their study earthquake impact and risk assessment on the Greater Metropolitan Manila Area, the total area of Quezon City is at 165.33 km2 (64 sq mi).[69][70]

Quezon City is bounded by Rodriguez and San Jose del Monte to the north, Marikina and San Mateo to the east, Pasig to the southeast, Mandaluyong and San Juan to the south, Manila to the southwest, and Caloocan and Valenzuela to the west and northwest. The city lies on the Guadalupe Plateau, a relatively high plateau at the northeast of the metropolis situated between the lowlands of Manila to the southwest and the Marikina River Valley to the east. The highest elevation in Quezon City is the northern tip of the La Mesa Watershed Reservation at 250 meters (820 ft) above sea level.[71] The West Valley Fault traverses the eastern border of the city.

Barangays and congressional districts

editRight: The six legislative districts of Quezon City.

Quezon City is politically subdivided into 142 barangays. These barangays are grouped into six congressional districts, with each district being represented by a congressman in the House of Representatives. Each congressional district has six City Councilors. The number of barangays per district is: District I, 37; District II, 5; District III, 37; District IV, 38; District V, 14; and District VI, 11; Although District II has the fewest barangays, it is the biggest in land area, including the Novaliches Reservoir.

- District I (2015 population: 409,962)[72] covers barangays Alicia, Bagong Pag-asa, Bahay Toro, Balingasa, Bungad, Damar, Damayan, Del Monte, Katipunan, Mariblo, Masambong, N.S. Amoranto (Gintong Silahis), Nayong Kanluran, Paang Bundok, Pag-ibig sa Nayon, Paltok, Paraiso, Phil-Am, Ramon Magsaysay, Salvacion, San Antonio, San Isidro Labrador, San Jose, Santa Cruz, Santa Teresita, Santo Cristo, Talayan, Veterans Village and West Triangle. It has an area of 19.59 km2 (7.56 sq mi).[73]

- District II (2015 population: 688,773)[72] covers barangays Bagong Silangan, Batasan Hills, Commonwealth, Holy Spirit and Payatas. It is the most populous district in the country from 1987 to 2013, before it was partitioned and its northern part became the 5th District and its western part became the 6th District.

- District III (2015 population: 324,669)[72] covers barangays Amihan, Bagumbuhay, Bagumbayan, Bayanihan, Blue Ridge A, Blue Ridge B, Camp Aguinaldo, Claro, Dioquino Zobel, Duyan-Duyan, E. Rodriguez, East Kamias, Escopa I, Escopa II, Escopa III, Escopa IV, Libis, Loyola Heights, Mangga, Marilag, Masagana, Matandang Balara, Milagrosa, Pansol, Quirino 2-A, Quirino 2-B, Quirino 2-C, Quirino 3-A, Saint Ignatius, San Roque, Silangan, Socorro, Tagumpay, Ugong Norte, Villa Maria Clara, West Kamias and White Plains.

- District IV (2015 population: 446,122)[72] covers barangays Bagong Lipunan ng Crame, Botocan, Central, Kristong Hari, Damayang Lagi, Doña Aurora, Doña Imelda, Doña Josefa, Don Manuel, East Triangle, Horseshoe, Immaculate Conception, Kalusugan, Kamuning, Kaunlaran, Krus na Ligas, Laging Handa, Malaya, Mariana, Obrero, Old Capitol Site, Paligsahan, Pinyahan, Pinagkaisahan, Roxas, Sacred Heart, San Isidro Galas, San Martin de Porres, San Vicente, Santo Niño, Santol, Sikatuna Village, South Triangle, Tatalon, Teachers Village East, Teachers Village West, U.P. Campus, U.P. Village and Valencia.

- District V (2015 population: 535,798)[72] covers barangays Bagbag, Capri, Fairview, Greater Lagro, Gulod, Kaligayahan, Nagkaisang Nayon, North Fairview, Novaliches Proper, Pasong Putik Proper, San Agustin, San Bartolome, Santa Lucia and Santa Monica. It is more commonly known as Novaliches.

- District VI (2015 population: 531,592)[72] covers barangays Apolonio Samson, Baesa, Balon-Bato, Culiat, New Era, Pasong Tamo, Sangandaan, Sauyo, Talipapa, Tandang Sora and Unang Sigaw.

Climate

edit| Quezon City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to the Köppen climate classification, Quezon City has a tropical monsoon climate (Am). The city has a dry season from December to April, in which in turn, divided into cool and warm dry seasons, and a prolonged wet season from May to November that brings heavy rains in some areas.

The primary weather station of the city is located at the PAGASA Science Garden. It has been observed that extreme temperatures ranged from a record high of 38.5 °C (101.3 °F) to a record low of 14.9 °C (58.8 °F).[75] The hot season was observed for 1.5 months, from April to May, with an average daily high temperature of 32.8 °C (91.0 °F). Meanwhile, the cool season lasts for 2.6 months, from November to February, with an average temperature of below 30.5 °C (86.9 °F).[76]

About 20 typhoons enter the Philippines every year, affecting Quezon City and the rest of Metro Manila. In recent years, heavy rainfalls from Habagat (south west monsoon) became as destructive as typhoons, triggering floods and landslides which endangers the city's residents living near the riverbanks.[68]

| Climate data for Science Garden, Quezon City (1991–2020, extremes 1961–2024) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.7 (94.5) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

38.2 (100.8) |

38.5 (101.3) |

38.0 (100.4) |

36.2 (97.2) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.4 (95.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.9 (94.8) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.1 (91.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.1 (89.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.0 (78.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.1 (1.07) |

24.4 (0.96) |

32.9 (1.30) |

41.7 (1.64) |

211.9 (8.34) |

322.7 (12.70) |

516.6 (20.34) |

568.5 (22.38) |

500.3 (19.70) |

283.6 (11.17) |

141.4 (5.57) |

114.5 (4.51) |

2,785.6 (109.67) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 17 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 15 | 12 | 8 | 143 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 73 | 70 | 68 | 73 | 79 | 83 | 85 | 84 | 82 | 81 | 80 | 78 |

| Source: PAGASA[74][75] | |||||||||||||

City districts

editQuezon City is politically subdivided into six legislative districts. However, the city is also divided into non-legislative or informal districts based on its historical origins. For instance, the district of San Francisco del Monte, which is not listed as a legislative district, was originally a pueblo owned by Franciscan missionary Fray Pedro Bautista.[77] Additionally, the Diliman Quadrangle was planned to be the city center of Quezon City.[78]

- Bago Bantay: Located at the west central part of the city, this place is known as a residential area at the back of SM North EDSA. It is composed of barangays Alicia, Ramon Magsaysay, Santo Cristo, and the northern part of Bagong Pag-asa. Bago-Bantay started as a small visita in the early 1930s under the jurisdiction of San Pedro de Bautista parish in San Francisco del Monte.[80][unreliable source] This area mark as part of North EDSA portion from North Avenue and West Avenue stretches all the way to Congressional Avenue and Fernando Poe Jr. Avenue with Project 7.

- Cubao: Located at the southern part of the city, Cubao is the home of the 35-hectare Araneta City, a mixed-use township development that contains prominent shopping malls such as Ali Mall, Farmers Plaza and Gateway Mall and iconic landmarks such as the Smart Araneta Coliseum. The Cubao Cathedral is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cubao.

- Diliman: Diliman is located at the center of Quezon City, the place where the city was originally established. The area is named for the Tagalog word for the medicinal fern species Stenochlaena palustris,[81][82] Numerous national government offices are located in Diliman, as well as prominent colleges and universities such as the University of the Philippines Diliman, FEU–FERN College, and New Era University. The Diliman Quadrangle, which is bounded by the North, West, South (Timog) and East Avenues, is known for its hospitals, government edifices, and nightlife bars.[citation needed] Several streets in South Triangle and Barangay Laging Handa were named in honor of the 22 Boy Scouts who died in a plane crash en route to joining the 11th World Scout Jamboree. A memorial stands in the center of the roundabout at the intersection of Timog Avenue and Tomas Morato Avenue. The place was thus known as the Scout Area. Major commercial broadcasting media and television networks such as ABS-CBN and GMA have their headquarters within the Diliman Quadrangle. PTV, RPN, IBC, and PBS also hold headquarters in Diliman.

- Galas: The Galas-Santol District of Quezon City is located in its southwest border with the City of Manila. The barangays of Dona Imelda, Dona Josefa, Dona Aurora and Don Manuel, named after public figures who significantly contributed to the city's early development, are located in this area. Barangays of Santo Nino, Santol and San Isidro serve as the border of Sampaloc and Santa Mesa in Manila. SM City Sta. Mesa lies at the end of the Araneta avenue set as the crossing border within the three cities of San Juan, Quezon City and Manila.

- La Loma: La Loma is located the southwestern portion of the city. It has five barangays along the vicinity of its main streets: N.S. Amoranto Avenue (Retiro) and A. Bonifacio Avenue. The district is famed as the birthplace of many popular Filipino culinary figures and establishments especially devoted to the lechon. The nearby La Loma Cemetery is named after this place.

- New Manila: New Manila is named after the City of Manila, since most of its residents are affluent families from the city who wished to escape the stress of living in the capital. It was formerly a part of San Juan before being carved out from its mother town to form Quezon City. Among its notable residents are the Hemady-Ysmael Family, the original landowner of New Manila, and Dona Narcisa de Leon, the matriarch of LVN Studios. It is also the birthplace of Eraño Manalo, the Second Executive Minister of Iglesia ni Cristo.[83] New Manila is also known for Balete Drive, which a haunted place according to Filipino folklore where the spirit of a white lady haunts the road seeking help from passing drivers.[84][85]

- Novaliches: Novaliches is the largest district in Quezon City, which made up almost all the northern portion of the city after Batasan Hills. It contains the La Mesa Watershed Reservation and its Dam and Reservoir where most of Metro Manila's water supply came from. It was originally a part of Caloocan before being incorporated to Quezon City in 1948, when the latter was declared as the capital. Before the place was incorporated to Quezon City in 1948, Novaliches was already in the maps as early as 1864, having been organized by the Spanish as early as 1855, from the haciendas of Tala, Malinta, Piedad, and Maysilo. By 1856, it was its own municipality before being absorbed by Caloocan in 1901. Novaliches is still known by its historical boundaries. The whole of North Caloocan up to the banks of the Marilao River bordering Bulacan to the north, parts of the historic Polo section of Valenzuela to the west, and parts of San Jose del Monte, Bulacan to the upper reaches of Tungkung Mangga and the old Tala Leprosarium in the northeast and east, are still referred to as within the old enclave of Novaliches that many residents consider to this day.

- Project 1: Also known as Barangay Roxas or Roxas District. Barangay Roxas was the first housing project undertaken by the Philippine Homesite Housing Corporation in compliance with an Executive Order by President Manuel Roxas in 1948.[86]

- Project 2: Made up of barangays Quirino 2-A, Quirino 2-B and Quirino 2-C. Specifically known as Anonas.

- Project 3: Made up of barangays Quirino 3-A, Amihan, Claro and Duyan-Duyan. Specifically known as Anonas.

- Project 4: Located within the eastern area beside Cubao.

- Project 5: Also known as Barangay E. Rodriguez.

- Project 6: Project 6 in Diliman is an affluent barangay which is known for hospitals such as the Philippine Children's Medical Center (PCMC) and the Veterans Memorial Medical Center (VMMC), as well as the home of Philippine Science High School Main Campus. The Office of the Ombudsman and the Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife Center are located here.

- Project 7: Project 7 is made up of barangays Bungad and Veterans Village.[87]

- Project 8: Project 8 is made up of barangays Bahay Toro, Baesa and Sangandaan.[88]

- San Francisco del Monte: San Francisco del Monte was founded as a pueblo by Saint Pedro Bautista in 1590, is considered as Quezon City's oldest district. The original land area of the old town was approximately 2.5 square kilometers (1.0 sq mi), including parts of Project 7 and 8 and Timog Avenue. It is bounded by West Avenue on the east, Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue on the north, Quezon Avenue on the south, and Araneta Avenue on the west. It was originally a part of San Juan, before it was carved out of its mother town to form Quezon City. The district is made up of barangays San Antonio, Paraiso, Paltok, Mariblo, Masambong, Manresa, Damayan and Del Monte. SFDM featured a hilly topography with lush vegetation and mineral springs, in the midst of which the old Santuario de San Pedro Bautista was built as a retreat and monastery for Franciscan friars. The headquarters of IBC is located here.

- Santa Mesa Heights: Santa Mesa Heights is an affluent neighborhood where many middle-class and upper-middle-class families reside. It is mostly residential. It is the home to the National Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes and the National Shrine of Our Lady of La Naval. Prominent Catholic educational institutions such as the Angelicum College, Lourdes School of Quezon City, and St. Theresa's College of Quezon City are located here. During the Commonwealth Period, Santa Mesa Heights was considered as the ideal site for universities, located just outside the suburban city limits of Manila. It is also the location of Banawe Street, a Chinatown-like place popular for its Asian restaurants and food hub haven.

Cityscape

editArchitecture

editThe architecture in Quezon City features a wide variety of architectural styles, such as Art Deco, Brutalist, International Modern, Postmodern and Contemporary styles.[citation needed] The city also has numerous monuments and museums. When the city was created in 1939, Art Deco was the prevailing architectural style, moving forward from the colonial designs of Bahay na bato by the Spanish, and the Neoclassical style by the Americans. The choice of designing buildings in contemporary international style was intentional to show that the Philippines was moving forward since it was anticipating independence in 1945.[90]

The Quezon Memorial Shrine, which was built from 1952 to 1978, was designed in Art Deco style. It became the city's symbol and at its base was a museum and mausoleum dedicated to the late Manuel L. Quezon and his wife Aurora. When the city became the capital in 1948, a lot of government buildings transferred from Manila to Quezon City. Numerous government buildings were built during the terms of President Elpidio Quirino, Ramon Magsaysay, Carlos P. Garcia, Diosdado Macapagal and Ferdinand Marcos. However, it was only during the term of Marcos that began the Filipinization of architecture. Numerous government hospitals in the city such as the Lung Center of the Philippines, Philippine Heart Center, and the Kidney Center of the Philippines were built and regarded as "designer" hospitals.[91] Traditional Filipino design motifs were incorporated in government buildings such as the Batasang Pambansa, which drew inspiration from the Bahay Kubo and the Bahay na bato.[92] Most of the government buildings and structures built during the time of Marcos were associated with the "edifice complex" of the Marcoses.[93]

Master Plans

editIn 1938, President Manuel L. Quezon made a decision to push for a new capital city. Manila was getting crowded, and his military advisors reportedly told him that Manila, being by the bay, was an easy target for bombing by naval guns in case of attack.[59][60] The new city will be located at least 15 km (9 mi) away from Manila Bay, which is beyond the reach of naval guns. Quezon contacted William E. Parsons, an American architect and planner, who had been the consulting architect for the islands early in the American colonial period. Parsons came over in the summer of 1939 and helped select the Diliman (Tuason) estate as the site for the new city. Unfortunately, he died later that year, leaving his partner Harry Frost to take over. Frost collaborated with Juan Arellano, engineer A.D. Williams, and landscape architect and planner Louis Croft to craft a grand master plan for the new capital. The plan was approved by the Philippine authorities in 1941.[59][60]

The core of the new city was to be a 400-hectare (990-acre) Central Park, about the size of New York's Central Park, and defined by the North, South (Timog), East and West Avenues. On one corner of the proposed Diliman Quadrangle was delineated a 25-hectare (62-acre) elliptical site, the focal point of the grand quadrangle. This was the planned location of a large Capitol Building to house the Philippine Legislature and ancillary structures for the offices of representatives.[59][60] On either side of the giant ellipse were supposed to have been the new Malacañang Palace on North Avenue (site of the present-day Veterans Memorial Hospital), and the Supreme Court Complex along East Avenue (now the site of East Avenue Medical Center). The three branches of government were to be finally and efficiently located in close proximity to each other.[59][60]

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1939 | 39,013 | — |

| 1948 | 107,977 | +11.98% |

| 1960 | 397,990 | +11.48% |

| 1970 | 754,452 | +6.60% |

| 1975 | 956,864 | +4.88% |

| 1980 | 1,165,865 | +4.03% |

| 1990 | 1,669,776 | +3.66% |

| 1995 | 1,989,419 | +3.34% |

| 2000 | 2,173,831 | +1.92% |

| 2007 | 2,679,450 | +2.93% |

| 2010 | 2,761,720 | +1.11% |

| 2015 | 2,936,116 | +1.17% |

| 2020 | 2,960,048 | +0.16% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[6][94][95][96][97] | ||

According to the 2020 Philippine census, Quezon City has a population of 2,960,048 people, making it the most populous city in the Philippines.[98] As of the 2015 census, the population of Quezon City comprises 22.80% or about 1⁄4 of Metro Manila's population.[98] From a population of 39,013 people when the city was established in 1939, the city tremendously grew and reached the one million mark in 1980 with a population of 1,165,865.[98] The city reached another milestone when its population reached the two million mark in 2000 with a population of 2,173,931.[98] The city's population density is at 18,222 people per km2, lower than Metro Manila's population density at 20,247 people per km2.[98] As of 2020, the city's most populous barangay is Commonwealth with 198,285 inhabitants, while the least populous is Quirino 3-A with 1,140 inhabitants.[98]

As of 2015, the average size of a household in Quezon City is 4.3 members.[98] It has a generally young population with an average of 28 years.[98] Females comprise 50.71% (1,488,765) while males comprise 49.29% (1,447,351). Children and youth alone (0–30 years old) constitute more than half (58.78% or 1,725,832) of the city's total population.[98]

Tagalog, which is spoken natively by 46.78% of the city's population, is the most spoken language in Quezon City.[98] Among the more minor languages spoken in the city is Bisaya/Binisaya (13.47%), followed by Bikol (9.03%), Ilocano (8.13%), Hiligaynon/Ilonggo (4.34%), Pangasinan/Pangasinense (2.64%), Cebuano (2.55%), Kapampangan (1.72%), Masbateño (0.57%), Boholano (0.51%) and other languages (10.23%).[98]

Religion

editReligion in Quezon City[98]

Quezon City is a predominantly Roman Catholic city, with the religion being followed by about 86.25% of its population.[98] The city is home to the seats of the Roman Catholic Dioceses of Cubao and Novaliches. It is followed in size by various Protestant faiths, which have seen a significant increase in membership over recent decades and are well represented in Quezon City.[98][99][100] The third largest religion is Iglesia ni Cristo, whose Central Temple and main office are located along Commonwealth Avenue in New Era.[98] Finally, a significant population of Quezon City belongs to the Islamic faith, the fourth largest religion in the city.[98]

Protestantism has strong presence in Quezon City. Several Evangelical, Protestant and Charismatic churches have their main headquarters, churches, and seminaries in the city. The main headquarters of the National Council of Churches in the Philippines (NCCP), Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches (PCEC) and the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) are located in the city. The Episcopal Church in the Philippines has its national office in Cathedral Heights, New Manila, including the National Cathedral of Saints Mary and John.

Jesus Is Lord Church Worldwide (JIL) has many branches in the city. The church is currently building the JIL Cornerstone Central, a 12-storey, 5,000 seating worship center located in Balintawak.[101] Jesus Miracle Crusade held its weekly service at Amoranto Sports Complex, with thousands of people in attendance. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has the Manila Philippines Temple and the Missionary Training Center located at Temple Drive, Green Meadows Subdivision in Ugong Norte. The Iglesia Filipina Independiente (Aglipayan Church) has three parishes located in the city: the Parish of the Crucified Lord in Apolonio Samson, Parish of the Holy Cross inside the UP Diliman Campus, and the Parish of the Resurrection in Balingasa. The Philippine Branch office of the Jehovah's Witnesses is located along Roosevelt Avenue. The headquarters of the UCKG HelpCenter (Universal Church of the Kingdom of God) is located at the former Quezon Theater in Araneta City, Cubao. There are also numerous Members Church of God International (Ang Dating Daan) churches in the city.

Other churches that have their main churches in the city include Bread of Life Ministries International, The Church So Blessed, People of Grace Fellowship, Tabernacle of Faith International, Word of Hope Christian Family Church, and Jesus the Blessed Redeemer International Ministry (JBRIM).[102]

Poverty, housing and urban slums

editAs of 2013, there are 196,818 informal settler families in Quezon City living in 151,890 structures. 48,927 of these families live along waterways, along right of ways, or within other danger areas.[111]

The Quezon Task Force on Socialized Housing and Development of Blighted Areas (Task Force Housing) is the lead agency of the city government for addressing the needs of socialized housing within the city.[98] Its goal is to direct and coordinate various city departments to develop housing projects and conduct other community development related activities.[98] The goal of the city's socialized housing program is to provide a safe, decent and sustainable home for the city's informal settlers and slum dwellers. The program involves the collaboration between different national and local government agencies, including the private sector.[112] The flagship housing program of the city is the Bistekville communities, which were named by former Mayor Herbert "Bistek" Bautista after himself while he was in office from 2010 to 2019.[113] The naming was controversial to an extent, for it was considered a form of political epal because his name was affixed on a public works project. As of 2018, Quezon City has 37 Bistekville projects with 7,184 beneficiaries.[114] Additionally, there are 960 housing units built by the National Housing Authority (NHA) in barangay Holy Spirit.[115]

Economy

editQuezon City is a hub for business and commerce, as a center for banking and finance, retailing, transportation, tourism, real estate, entertainment, new media, traditional media, telecommunications, advertising, legal services, accountancy, healthcare, insurance, theater, fashion, and the arts in the Philippines. The National Competitiveness Council of the Philippines which annually publishes the Cities and Municipalities Competitiveness Index (CMCI), ranks the cities, municipalities and provinces of the country according to their economic dynamism, government efficiency and infrastructure. Quezon City was the Most Competitive City in the country from 2015 to 2019 assuring that the city is consistently one of the best place to live in and do business. It earned the Hall of Fame Award in 2020 for its consecutive top performance.[116] There are about 86,000 registered business in the city.[117] As of 2019, Quezon City is the second richest city in the Philippines after Makati. The city's total asset stood at ₱96.4 billion,[118][119] while it has the biggest liability at ₱21.624 billion.[119] Since 2020, Quezon City is the richest city in the Philippines. The city's total assets amounted to ₱448.51 billion by the end of 2023.[120][121]

Information and communications technology

editQuezon City bills itself as the ICT capital of the Philippines.[122] Quezon City was the first Local Government Unit (LGU) in the Philippines with a computerized real estate assessment and payment system, which was developed in 2015 that contains around 400,000 property units with capability to record payments.[59][60] The city has 33 ICT parks according to PEZA, which includes the Eastwood City Cyberpark in Bagumbayan, the first and largest IT Park in the country.[123]

The Department of Information and Communications Technology and National Telecommunications Commission of the Philippines have their respective headquarters in the city.

Media and entertainment

editQuezon City is known as the "Entertainment Capital of the Philippines"[122] and the "City of Stars", since it is where major studios located and most Filipino actors and actresses reside.[123] To support the film industry, the city established the Quezon City Film Development Commission (QCFDC). The city also holds its own film festival, the QCinema International Film Festival, every October or November and showcases local and international films, documentaries, and short films, and gives grants to their creators.[124][125][126]

Quezon City is home to the Philippines' major broadcasting networks. There are 11 local television networks, 6 cable TV, 7 AM radio stations, and 4 FM radio stations in the city.[5] Major commercial broadcast network in the Philippines such as ABS-CBN and GMA Network have their headquarters in the city. From 1992 to 2013, TV5 had its headquarters in the city. It moved to Mandaluyong in 2013 although TV5's former Novaliches headquarters still serves as its alternate studios. Its transmitter in Novaliches is still being used and operated by the network.[127] State-owned media and television network such as RPN, IBC and PTV also have their headquarters in the city.

Minor/religious broadcasting companies in the city include CEBSI (formerly CBS), DZCE-TV and EBC (Net 25), which are all affiliated with Iglesia ni Cristo. UNTV is another minor/religious broadcasting network affiliated with Members Church of God International. DZRV-AM, owned and operated by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila, has a studio in the city. Major broadcasting facilities in the city include the Net 25 Tower, the tallest communications tower in the Philippines standing at 907 feet (276 m), RPN's South Tower (492 ft (150.0 m)), GMA's Tower of Power (777 ft (236.8 m)), IBC's Central Tower (650 ft (198.1 m)), TV5's Satellite Tower (656.2 ft (200.0 m)), ABS-CBN's/AMBS' Millennium Transmitter (720 ft (219.5 m)), the ABS-CBN's ABS-CBN Broadcasting Center, GMA Network Center, TV5's alternate studios in Novaliches, and the UNTV Broadcast Center. Formerly, the Broadcast City in Matandang Balara was once home to Banahaw Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Radio Philippines Network (RPN) and Intercontinental Broadcasting Corporation (IBC).

Government

editLocal government

editQuezon City is classified as a Special City (according to its income)[128][129] and a highly urbanized city (HUC). The mayor is the chief executive, and is a member of the Metro Manila Council. The mayor is assisted by the vice mayor, who serves as the presiding officer of the 38-member Quezon City Council. The members of the City Council are elected as representatives of the four councilor districts within the city, and the municipal presidents of the Liga ng mga Barangay and Sangguniang Kabataan.

The current mayor is Maria Josefina "Joy" Belmonte, who previously served as the city's vice mayor and is the daughter of former mayor and House Speaker Feliciano Belmonte Jr. The current vice mayor is Gian Sotto, a former city councilor and the son of actors Tito Sotto (also a former Senate President and city vice mayor) and Helen Gamboa. The mayor and the vice mayor are term-limited by up to 3 terms, with each term lasting for 3 years. The mayor serves as the executive head that leads all the city's department in executing city ordinances and improving public services. The vice mayor, who serves a concurrent position as the presiding officer of the City Council, oversees the formulation and enactment passed by the council.

From its creation in 1939 up until 1959, the mayors of Quezon City were appointed by the President. Norberto S. Amoranto was the first elected mayor, and was the city's longest-serving mayor, having served that position for 22 years.[25]

The city observes regular and non-working holidays of the Philippines. The Quezon City Day, which was celebrated annually on August 19 by both Quezon City and Quezon Province to commemorate the birth of Manuel L. Quezon, is a special non-working holiday.[130]

Elected officials

editNational government

editAs the former capital, the city is the home to numerous government departments, agencies and institutions. The House of Representatives of the Philippines (Lower House), as well as the Departments of Agrarian Reform, Agriculture, Environment and Natural Resources, Human Settlements and Urban Development, Information and Communications Technology, Interior and Local Government, National Defense and Social Welfare and Development calls the city home. Independent constitutional bodies such as the Commission on Audit and the Office of the Ombudsman, as well as special courts such as the Court of Tax Appeals and the Sandiganbayan are located in the city.

There are two National Government Centers (NGC) in the city. The first National Government Center is located at Diliman Quadrangle, which is bounded by the North, South, East and West Avenues. The proposed Capitol Building of the Philippines is supposed to rise at the site of the Quezon Memorial Circle, while the Executive Mansion was planned to be constructed at the present-day Veterans Memorial Medical Center (VMMC) and the Supreme Court was supposed to rise at the present-day East Avenue Medical Center (EAMC). This is where the main offices of the Departments of Agrarian Reform, Agriculture, Environment and Natural Resources, Human Settlements and Urban Development (including the National Housing Authority (Philippines)) and the Interior and Local Government are located. Other government agencies located within the city are the Bureau of Internal Revenue, BSP Security Plant Complex, Land Registration Authority, Land Transportation Office, National Power Corporation (NAPOCOR/NPC), National Transmission Corporation (TransCo), Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA), Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) and the Social Security System (SSS).

The second National Government Center is located along Commonwealth Avenue, Batasan Hills. It is where the Batasang Pambansa Complex is located, whose site is supposed to be the national civic center and the focal point of the 1949 Master Plan. The Commission on Audit (COA), Public Attorney's Office (PAO) and the Sandiganbayan are located here.

Sports

editSports in Quezon City have a long and distinguished history. Quezon City is the home to notable sporting and recreational venues such as the Amoranto Sports Complex, Quezon City Sports Club and the Smart Araneta Coliseum. The prominent boxing fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, which was known as Thrilla in Manila" was held at the Araneta Coliseum. It was renamed as the "Philippine Coliseum" for the event and the match was watched by over 1 billion viewers worldwide. The city is also home to venues used during the 1981, 1991, 2005, and 2019 editions of the Southeast Asian Games.

The Araneta Coliseum has hosted numerous sporting events, including the 1978 and 2023 editions of the FIBA Basketball World Cup, as well as multiple games in the Philippine Basketball Association.

Basketball is very prominent in the country. The city is home to the Quezon City Toda Aksyon, a men's professional basketball team that joined the Maharlika Pilipinas Basketball League in 2018. Most barangays around the city have a basketball court (or at least a makeshift basketball court), with court markings drawn on the streets. Larger barangays have covered courts where inter-barangay leagues are held every summer.

Quezon City is also notable for its golf courses, such as the Veterans Memorial Golf Club and Camp Aguinaldo Golf Club, which operates on golf-courses owned by the national government. The Capitol Hills Golf & Country Club in Matandang Balara is a privately owned exclusive 18-hole golf course situated at the hills overlooking Marikina Valley. In the early days after the creation of the city, Greenhills was considered as part of it along with Wack Wack Golf and Country Club, but the golf course was reverted to Mandaluyong.

Healthcare

editThe Quezon City Health Department is responsible for the public health of the city. Its headquarters is located at the Batasan Social Hygiene Clinic Building along IBP Road, Batasan Hills. There are 60 government and privately owned hospitals in the city.[122] At present, there are three city-owned and controlled hospitals: the Quezon City General Hospital in Bahay Toro (Project 8), Novaliches District Hospital in San Bartolome, Novaliches and the Rosario Maclang Bautista General Hospital in Batasan Hills. Another city-owned hospital, the Visayas Avenue Medical Center is currently under-construction.[131]

There are several hospitals operated by the national government such as the East Avenue Medical Center (EAMC), Quirino Memorial Medical Center and the 55-hectare (140-acre) Veterans Memorial Medical Center (VMMC), which is operated by the Department of National Defense. The national government also operates several specialty hospitals in the city such as the Lung Center of the Philippines, National Kidney and Transplant Institute (NKTI), Philippine Heart Center and the Philippine Orthopedic Center. There are two government-owned children's hospital in the city: the Philippine Children's Medical Center along Quezon Avenue, and the National Children's Hospital in E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue. The Armed Forces of the Philippines operates the V. Luna General Hospital (AFP Medical Center).

The city's healthcare is also provided by non-profit corporations, such as the Quezon Institute. There are numerous privately owned hospitals in the city, such as the Ace Medical Center, Bernardino General Hospital, Capitol Medical Center, Commonwealth Hospital and Medical Center, De Los Santos Medical Center, Diliman Doctor's Hospital, the Far Eastern University – Nicanor Reyes Medical Foundation Medical Center, J. P. Sioson General Hospital, St. Luke's Medical Center – Quezon City, UERM Memorial Hospital, United Doctors Medical Center, Villarosa Hospital and the World Citi Medical Center.

Education

editThe Schools Divisions Office of Quezon City (SDO QC) oversees the 97 public elementary schools and 46 public high schools within the city. The number of students enrolled in public schools across the city has increased over time, from an initial population of 20,593 elementary pupils and 310 high school students in 1950 to 258,201 elementary pupils and 143,462 high school students in the 2013–14 school year.[132] With its large student population, Quezon City has the greatest number of public schools in the Philippines.[133] As of 2015, five of the city's elementary schools and four of its high schools are among the 15 most populous public schools in the Philippines.[134] The Quezon City Science High School (QueSci) was designated as the Regional Science High School for the National Capital Region since 1998. The city is the home of the Philippine Science High School, the top science school in the Philippines operated by the Department of Science and Technology.

The Quezon City Science Interactive Center is regarded as the first of its kind science interactive center in the Philippines. The Quezon City Public Library (QCPL) operates 20 branches throughout the city, with its Main Library located within the Quezon City Hall Complex.

Higher education

editQuezon City, along with Manila, is the center for education in the Philippines. There are two state universities within the city limits: the University of the Philippines Diliman (UPD) and the Quezon City branch campus of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines. The city-run Quezon City University (QCU) has established three campuses around the city: San Bartolome, San Francisco and Batasan Hills.

Private universities include the AMA Computer University, Central Colleges of the Philippines (CCP), FEU Diliman, Kalayaan College, National College of Business and Arts (NCBA), the Technological Institute of the Philippines (TIP).

Quezon City hosts prestigious Catholic educational institutions such as the Ateneo de Manila University (AdMU), Immaculate Heart of Mary College, St. Paul University Quezon City, Saint Pedro Poveda College, Siena College of Quezon City and the UST Angelicum College. It is also the home to other sectarian colleges and universities such as the Evangelical Grace Christian College, Episcopalian-run Trinity University of Asia, and the Iglesia ni Cristo founded New Era University (NEU).

The presence of medical schools has made Quezon City a center of healthcare and medical education. These include FEU Nicanor Reyes Medical Foundation, St. Luke's College of Medicine, Capitol Medical Center Colleges, and the University of the East Ramon Magsaysay Memorial Medical Center (UERMMMC).

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editTransportation in the city is purely land based. As of 2006, the MMDA Traffic Operation Center revealed that the most dominant type of transport in the city is private transportation, accounting for 82.49% of the total volume, while public transport such as buses, and jeepneys and taxis make up 13.72%, followed by industrial and commercial vehicles (such as trucks and vans) at 3.79%.[135] The Metro Manila Skyway is the only elevated expressway passing through Quezon City, serving as a tolled connector between the North and South Luzon Expressways. The proposed Southeast Metro Manila Expressway (C-6 Expressway) will connect parts of Quezon City and will have its northern terminus in Batasan Hills.

Famous modes of transportation in the city to get around are the jeepney, city buses and the UV Express, which follow fixed routes for a set price. All types of public road transport plying Quezon City are privately owned and operated under government-issued franchises. As of September 2020, the city has distributed 276 e-trikes in selected barangays in hopes of promoting energy efficient and clean technologies in the transport sector.[136]

In 2021, the city government began operating eight city-wide bus routes under the Quezon City Bus Augmentation Program. The service is also referred to as City Bus and the QCity Bus Service.[137][138] On April 28, 2023, the service was made permanent through Quezon City Ordinance No. SP-3184, series of 2023, or the "Q City Bus Ordinance", placing the program under the Quezon City Traffic and Transport Management Department.[139]

Railway systems

editQuezon City is served by LRT Line 1 (LRT-1), LRT Line 2 (LRT-2), and the MRT Line 3 (MRT-3). LRT-1 runs along the northern portion of EDSA (AH26/C-4), and ending at the North Triangle Common Station where it connects to Lines 1, 7 and the Subway. LRT-2 runs through Aurora Boulevard (R-6/N59/N180), connecting Quezon City to Manila, San Juan, Marikina, Pasig, Cainta and Antipolo. MRT-3 runs through EDSA (AH26/C-4), linking Quezon City to the cities of Mandaluyong, Makati and Pasay. Railway lines that are under-construction within the city are the MRT Line 4 (MRT-4), MRT Line 7 (MRT-7) and the Metro Manila Subway (MMS). The North Triangle Common Station, which will link Lines 1, 3, 7, and the Metro Manila Subway, is currently under construction at the intersection of EDSA and North Avenue.

Air

editThe city is served by Ninoy Aquino International Airport to the south and Clark International Airport to the north. In the future, it will also be served by the upcoming New Manila International Airport located in the adjacent province of Bulacan. All are located outside the city limits.

Utilities

editWater supply, power and telecommunications

editWater services is provided by Maynilad Water Services for the west and northern part of the city and Manila Water for the southeastern part. The Novaliches-Balara Aqueduct 4 (NBAQ4), constructed by Manila Water, is the largest water supply infrastructure project in Metro Manila.[140] NBAQ4 measures 7.3 kilometers (4.5 mi) long and 3.1 meters (10 ft) in diameter, and the aqueduct has a capacity of 1,000 MLD (millions of liters per day) or 1,000 kL (35,000 cu ft) per day.[141] The La Mesa Dam and Reservoir is situated at the northernmost part of the city, covering an area of more than 27 square kilometers (10 sq mi). The reservoir contains the La Mesa Watershed and Ecopark.i

Electric services are provided by Meralco, the sole electric power distributor in Metro Manila. As of December 2009, Meralco has a total of 512,255 customers within the city: 461,645 (90.1%) residential, 49,082 (9.6%) commercial, and 1,110 (0.2%) industrial. Street lights have 418 accounts.[5][142] As of October 2019, the city has 26,776 LED streetlights.[136]

With the liberalization of the telecommunications industry, the city benefitted by having more firms that offer telephone and internet services. Notable telecommunication companies operating in the city include PLDT/Smart Communications, Globe Telecom, Dito Telecommunity, Multimedia and Eastern Telecommunications Services, Inc.[5]

Domestic solid waste

editThe Payatas dumpsite was the largest landfill in Metro Manila. It was established in the 1970s on the barangay of the same, located at the northeast part of Quezon City. The area where the landfill is situated used to be a ravine surrounded by farming villages and rice paddies.[143] When the Smokey Mountain in Tondo, Manila, was closed in 1995, people who resided and worked as scavengers there migrated to the Payatas dumpsite, establishing a squatter colony around the dumpsite. On July 10, 2000, the deadly Payatas landslide occurred, when large heaps of garbage dump collapsed on a nearby informal settlers' community and burned, killing between 218 and 700 people.[144] Following the tragic collapse, Republic Act No. 9003 or the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 was passed, which mandates the closure of open dumpsites in the Philippines by 2004 and controlled dumpsites by 2006.[145] In 2004, the Payatas dumpsite was reconfigured as a controlled disposal facility but it was closed down in December 2010.[146] A separate dumpsite was established near the old open dumpsite in January 2011.[147][146] The newer dumpsite closed in December 2017.[145]

Sister cities

editAsia

edit- Alicia, Isabela, Philippines[148]

- Banaybanay, Davao Oriental, Philippines[148]

- Cagayan de Oro, Misamis Oriental, Philippines[149]

- Calasiao, Pangasinan, Philippines[148]

- Chiba, Japan[150]

- Cotabato City, Philippines[148]

- Davao City, Philippines[148][151]

- General Santos, Philippines[148][152]

- Hagåtña, Guam[150]

- Iloilo City, Philippines[148][153]

- La Trinidad, Benguet, Philippines[148]

- Puerto Princesa, Philippines[148]

- Pura, Tarlac, Philippines[148]

- Roxas City, Philippines[154]

- Sadanga, Mountain Province, Philippines[148]

- Shenyang, China[155][156]

- Taipei, Taiwan[157]

- Wao, Lanao del Sur, Philippines[148]

- Yangon, Myanmar[158]

- Yuci District, China[150]

Americas

edit- Caracas, Venezuela[150][159]

- Daly City, California, United States[150]

- Fort Walton Beach, Florida, United States[150]

- Kenosha, Wisconsin, United States[150]

- Maui County, Hawaii, United States[150]

- New Westminster, Canada[150]

- Salt Lake City, Utah, United States[150]

International relations

editAffiliates

edit- Osaka, Japan (2018)[160]

- Pyeongchang County, South Korea[161]

Consulates

edit| Country | Type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Cyprus | Consular agency | [162] |

In art

edit- Cubao Landscape, by Fernando Amorsolo, 1924.

- Novaliches Landscape, by Fernando Amorsolo, 1925.

- Landscape (The University of the Philippines Campus Site in Diliman), by Dominador Castañeda, 1941.

- Mira Nila, by Macario Vitalis, 1963.

Notable people

editSee also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ San Diego, Bayani Jr. (July 21, 2012). "QC, 'City of Stars,' goes indie". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Villamente, Jing (August 5, 2018). "Quezon City to host festival of Filipino films". The Manila Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019.

...a float parade and Grand Fans Day will be held in Quezon City which had been tagged the "City of Stars."

- ^ Quezon City | (DILG)

- ^ "2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Quezon City, Philippines. August 2016. ISSN 0117-1453. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Quezon City History". Quezon City Government. September 22, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Census of Population (2020). "National Capital Region (NCR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved July 8, 2021.