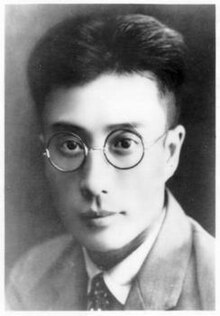

Qian Zhuangfei (Chinese: 钱壮飞; September 25, 1895 – April 1935) was a Chinese doctor, film director and a secret agent for the Chinese Communist Party. After the Kuomintang (KMT) began its suppression of the Communists in 1927, Qian infiltrated the KMT secret service, and in 1931 intercepted a telegram reporting the arrest and defection of the Communist leader Gu Shunzhang. His quick reaction allowed the Communist leadership in Shanghai to evacuate, and he was credited with saving the lives of top leaders including Zhou Enlai, later the Premier of China. Zhou called Qian and his fellow agents Li Kenong and Hu Di "the three most distinguished intelligence workers of the Party." Qian was killed in 1935 during the Long March. He was the father of Li Lili, one of China's most popular film stars in the 1930s.

Qian Zhuangfei | |

|---|---|

钱壮飞 | |

| |

| Born | September 25, 1895 |

| Status | Disappeared |

| Died | April 2, 1935 (aged 39) |

| Nationality | Republic of China |

| Alma mater | National Peking Medical School |

| Occupation(s) | Intelligence operative, spy, doctor |

| Employer | State Political Security Department of the Chinese Communist Party |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party |

| Other political affiliations | Kuomintang |

| Spouse | Zhang Zhenhua |

| Children | Li Lili |

Early life and career

editQian was born Qian Beiqiu (Chinese: 钱北秋) in 1895/1896 in Huzhou, Zhejiang Province. He also used the name Qian Chao (Chinese: 钱潮).[1][2]

After graduating from Huzhou High School,[1] he entered the National Peking Medical School (now Peking University Health Science Center) in 1914, and worked at Jiangsu Railway Hospital in Beijing as well as his own practice after graduating in 1919. He married a fellow doctor named Zhang Zhenhua.[3] He also taught anatomy in an art academy, and dabbled in filmmaking and radio transmission. The couple helped run a small film company,[3] and Qian wrote and directed the film Invisible Swordsman in 1926, starring his wife and daughter Qian Zhenzhen (later known as Li Lili).[4]

In 1925, Qian and his wife secretly joined the Chinese Communist Party, and used filmmaking and their medical practice as covers for their underground activities. Their best friend Hu Di also joined the party, and the three worked closely together.[5] After the KMT's Shanghai massacre of the Communists in Shanghai, Qian and his wife moved to Kaifeng where they briefly worked for the warlord Feng Yuxiang, before going to Shanghai at the end of 1927.[5]

Secret agent

editIn 1929, the Communist leader Zhou Enlai asked Qian to join a wireless radio training class in Shanghai. The class was run by Xu Enzeng, the head of the KMT's Investigation Department, to recruit special agents for the department.[6] Qian excelled in the class, and gained the trust of Xu, a fellow Huzhou native. Xu made him his "confidential secretary" and the chief coordinator of the central intelligence headquarters in Nanjing,[5] in charge of recruiting more special agents.[7] This created opportunities for Qian's fellow Communist agents, most notably Hu Di and Li Kenong, to join the KMT secret service as moles.[7] Their intelligence reports helped the Communist Red Army in Jiangxi thwart the first two of Chiang Kai-shek's Encirclement Campaigns.[7]

On 24 April 1931, Gu Shunzhang, Zhou Enlai's security chief and head of the Communist Party's dreaded Red Brigade, was arrested in Wuhan while on a mission to assassinate Chiang Kai-shek.[8][7] To save himself, Gu defected to the KMT, and disclosed his extensive knowledge about Communist organizations. Qian intercepted a telegram sent by the Wuhan police to the Nanjing headquarters, and immediately recognized the severity of the situation. He sent his son-in-law Liu Qifu on an express train to Shanghai to deliver the information to Li Kenong, who in turned informed Zhou Enlai and intelligence chief Chen Geng about Gu's arrest.[8][7] The top party leaders, including Zhou, Li Weihan, Kang Sheng, and Qu Qiubai, were able to evacuate, but many party members could not be warned in time and were arrested and executed, including 40 high-ranking and 800 ordinary members. It was the largest loss to the Communists since the 1927 massacre.[9][10] Qian's cover was blown and he escaped just before the order of his arrest arrived.[11]

Qian Zhuangfei, together with Chen Geng, Li Kenong, and Hu Di, was transferred to the Jiangxi Soviet Communist base,[1] where Li and Qian controlled the security forces.[12] Qian was also in charge of decoding the telegrams of the encircling KMT forces.[13]

Death and legacy

editIn 1934, the Communists were forced to evacuate the Jiangxi base area and begin the Long March.[13] In late March or early April 1935, Qian was killed during the Red Army's crossing of the Wu River in Jinsha County, Guizhou.[1][14]

Zhou Enlai later called Qian Zhuangfei, Li Kenong and Hu Di, "the three most distinguished intelligence workers of the Party",[6] and said that he and other Communist leaders owed their lives to them.[1] Li, the sole survivor of the three who lived to see the founding of the People's Republic of China, was awarded the military rank of general (shang jiang) in 1955, despite his lack of combat experience.[1]

Family

editQian Zhuangfei's daughter Qian Zhenzhen was born in June 1915. After Qian fled Nanjing for the Communist base, his daughter was adopted by Li Jinhui, the "father of Chinese popular music", and changed her name to Li Lili. She became one of the most popular movie stars of the 1930s, sometimes called "China's Mae West".[4]

Qian also had two sons, Qian Jiang (钱江) and Qian Yiping (钱一平). Qian Jiang was a well-known cinematographer and film director. In 1985, he directed the film Night in Jinling based on Qian Zhuangfei's life.[14]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f "共产党人中的著名卧底英雄". People's Daily (in Chinese). 20 December 2006.

- ^ "Qian Zhuangfei" (in Chinese). Xinhua. 27 July 2009. Archived from the original on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1995, p. 140.

- ^ a b Xiao & Zhang 2002, p. 219.

- ^ a b c Wakeman 1995, p. 141.

- ^ a b Barnouin & Yu 2006, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e Barnouin & Yu 2006, p. 46.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1995, p. 152.

- ^ Barnouin & Yu 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Stranahan 1998, p. 117.

- ^ Wakeman 1995, p. 153.

- ^ Guo 2012, p. 153.

- ^ a b Guo 2012, p. 318.

- ^ a b "缅怀情报专家钱壮飞". Chongqing Evening News (in Chinese). 31 March 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

Bibliography

edit- Barnouin, Barbara; Yu, Changgen (2006). Zhou Enlai: A Political Life. Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-962-996-280-7.

- Guo, Xuezhi (2012). China's Security State: Philosophy, Evolution, and Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02323-9.

- Stranahan, Patricia (1998). Underground: The Shanghai Communist Party and the Politics of Survival, 1927–1937. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-8723-7.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1995). Policing Shanghai, 1927–1937. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91865-8.

- Xiao, Zhiwei; Zhang, Yingjin (2002). Encyclopedia of Chinese Film. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-74554-8.