Puri, also known as, Jagannath Puri, (Odia: [ˈpuɾi] ) is a coastal city and a municipality in the state of Odisha in eastern India. It is the district headquarters of Puri district and is situated on the Bay of Bengal, 60 kilometres (37 mi) south of the state capital of Bhubaneswar. It is home to the 12th-century Jagannath Temple[3] and is one of the original Char Dham pilgrimage sites for Hindus.

Puri | |

|---|---|

City | |

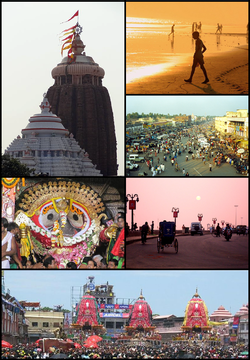

Montage of Puri City | |

| Nickname(s): Spiritual City, Sri Jagannath Dham | |

| Coordinates: 19°48′38″N 85°49′53″E / 19.81056°N 85.83139°E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| District | Puri |

| Named for | Jagannath Temple |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Puri Municipality |

| • Collector & District Magistrate | Sidhartha Shankar Swain, IAS[1] |

| • Superintendent of Police | Pinak Mishra, IPS[1] |

| • Member of Parliament | Sambit Patra, (BJP) |

| • Member of Legislative Assembly | Sunil Kumar Mohanty, (BJD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 16.84 km2 (6.50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0.1 m (0.3 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 200,564 |

| • Rank | India 228th, Odisha 5th |

| • Density | 12,000/km2 (31,000/sq mi) |

| Language | |

| • Official | Odia |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 752001 |

| Telephone code | 06752,06758 (06758 for Nimapara & 06752 for Puri) |

| Vehicle registration | OD-13 |

| Website | puri |

Puri has been known by several names since ancient times, and was locally known as "Sri Kshetra" and the Jagannath temple is known as "Badadeula". Puri and the Jagannath Temple were invaded 18 times by Muslim rulers, from the 7th century AD until the early 19th century with the objective of looting the treasures of the temple. Odisha, including Puri and its temple, were part of British India from 1803 until India attained independence in August 1947. Even though princely states do not exist in India today, the heirs of the House of Gajapati still perform the ritual duties of the temple. The temple town has many Hindu religious mathas or monasteries.

The economy of Puri is dependent on the religious importance of the Jagannath Temple to the extent of nearly 80 percent. The 24 festivals, including 13 major ones, held every year in the temple complex contribute to the economy; Ratha Yatra and its related festivals are the most important which are attended by millions of people every year. Sand art and applique art are some of the important crafts of the city.

Puri has been chosen as one of the heritage cities for Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana (HRIDAY) scheme of Government of India.

Puri is a significant part of the "Krishna pilgrimage circuit" which also includes Mathura, Vrindavan, Barsana, Gokul, Govardhan, Kurukshetra and Dwarka.[4]

History

editNames in history

editPuri, the holy land of Jagannatha, also known by the popular vernacular name Srikshetram, has many ancient names in the Hindu scriptures such as the Rigveda, Matsya purana, Brahma Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana, Skanda Purana, Kapila Purana and Niladrimahodaya. In the Rigveda, in particular, it is mentioned as a place called Purushamandama-grama meaning the place where the Creator deity of the world – Supreme Divinity deified on an altar or mandapa was venerated near the coast and prayers offered with Vedic hymns. Over time the name got changed to Purushottama Puri and further shortened to Puri, and the Purusha came to be known as Jagannatha. Sages like Bhrigu, Atri and Markandeya had their hermitage close to this place.[5] Its name is mentioned, conforming to the deity worshipped, as Srikshetra, Purusottama Dhāma, Purusottama Kshetra, Purusottama Puri and Jagannath Puri. Puri, however, is the popular usage. It is also known by the geographical features of its location as Shankhakshetra (the layout of the town is in the form of a conch shell),[6] Neelāchala ("Blue mountain" a terminology used to name a very large sand lagoon over which the temple was built but this name is not in vogue), Neelāchalakshetra, Neelādri.[7] In Sanskrit, the word "Puri" means town or city,[8] and is cognate with polis in Greek.[9]

Another ancient name is Charita as identified by General Alexander Cunningham of the Archaeological Survey of India, which was later spelled as Che-li-ta-lo by Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang. When the present temple was built by the Eastern Ganga king Anantavarman Chodaganga in the 11th and 12th centuries AD, it was called Purushottamkshetra. However, the Moghuls, the Marathas and early British rulers called it Purushottama-chhatar or just Chhatar. In Moghul ruler Akbar's Ain-i-Akbari and subsequent Muslim historical records it was known as Purushottama. In the Sanskrit drama Anargha Raghava Nataka as well, authored by Murari Mishra, a playwright, in the 8th century AD, it is referred to as Purushottama.[6] It was only after the 12th century AD that Puri came to be known by the shortened form of Jagannatha Puri, named after the deity or in a short form as Puri.[7] It is the only shrine in India, where Radha, along with Lakshmi, Saraswati, Durga, Bhudevi, Sati, Parvati, and Shakti, abodes with Krishna, who is also known by the name Jagannatha.[10]

Ancient period

editAccording to the chronicle Madala Panji, in 318 AD, the priests and servitors of the temple spirited away the idols to escape the wrath of the Rashtrakuta king Rakatavahu.[11] In the temple's historical records it finds mention in the Brahma Purana and Skanda Purana stating that the temple was built by the king Indradyumna, Ujjayani.[12]

S. N. Sadasivan, a historian, in his book A Social History of India quotes William Joseph Wilkins, author of the book Hindu Mythology, Vedic and Purānic as stating that in Puri, Buddhism was once a well established practice but later Buddhism faded and Brahmanism became the order of the religious practice in the town; the Buddha deity is now worshipped by the Hindus as Jagannatha. It is also said by Wilkinson that some relics of Buddha were placed inside the idol of Jagannatha which the Brahmins claimed were the bones of Krishna. Even during Maurya king Ashoka's reign in 240 BC, Kalinga was a Buddhist center and that a tribe known as Lohabahu (barbarians from outside Odisha) converted to Buddhism and built a temple with a statue of Buddha which is now worshipped as Jagannatha. Wilkinson also says that the Lohabahu deposited some Buddha relics in the precincts of the temple.[13]

Construction of the present Jagannath Temple started in 1136 AD and completed towards the latter part of the 12th century. The Eastern Ganga king Anangabhima III dedicated his kingdom to Jagannatha, then known as the Purushottama-Jagannatha, and resolved that from then on he and his descendants would rule under "divine order as Jagannatha's sons and vassals". Even though princely states do not exist in India today, the heirs of the Puri Estate still perform the ritual duties of the temple; the king formally sweeps the road in front of the chariots before the start of the Ratha Yatra. This ritual is called Cherra Pahanra.[14]

Medieval and early modern periods

editThe history of Puri is on the same lines as that of the Jagannath Temple, which was invaded 18 times during its history to plunder the treasures of the temple, rather than for religious reasons. The first invasion occurred in the 8th century AD by Rastrakuta king Govinda III (798–814 AD), and the last took place in 1881 AD by the monotheistic followers of Alekh (Mahima Dharma) who did not recognise the worship of Jagannatha.[15] From 1205 AD onward [14] there were many invasions of the city and its temple by Muslims of Afghan and Moghul descent, known as Yavanas or foreigners. In most of these invasions the idols were taken to safe places by the priests and the servitors of the temple. Destruction of the temple was prevented by timely resistance or surrender by the kings of the region. However, the treasures of the temple were repeatedly looted.[16] The table lists all the 18 invasions along with the status of the three images of the temple, the triad of Jagannatha, Balabhadra and Subhadra following each invasion.[15]

| Invasion number | Invader (s), year (s) AD | Local rulers | Status of the three images of the Jagannath temple |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raktabahu or Govinda III (798–814) of the Rashtrakuta Empire | King Subhanadeva of Bhaumakara dynasty | Idols shifted to Gopali near Sonepur. Was brought back to Puri by Yayati I after 146 years and re-consecrated after performing Nabakalebara.[17] |

| 2 | Illias Shah, Sultan of Bengal, 1340 | Narasinghadeva III | Images shifted to a secret location.[18] |

| 3 | Feroz Shah Tughlaq, 1360 | Ganga King Bhanudeva III | Images not found, though rumored that they were thrown into the Bay Of Bengal.[18] |

| 4 | Ismail Ghazi commander of Alauddin Hussain Shah of Bengal, 1509 | King Prataprudradeva | Images shifted to Chandhei Guha Pahada near Chilika Lake.[18] |

| 5 | Kalapahara, army assistant general of Sulaiman Karrani of the Afghan Sultan of Bengal, 1568 | Mukundadeva Harichandan | Images initially hidden in an island in Chilika Lake. However, the invader took the idols from here to the banks of the Ganges River and burnt them. Bisher Mohanty, a Vaishnavite saint, who had followed the invading army, retrieved the Brahmas and hid it in a drum at Khurdagada in 1575 AD and finally re-installed it in the deities. Deities were brought back to Puri and consecrated in the Jagannath Temple.[19] |

| 6 | Suleman, the son of Kuthu Khan and Osman, the son of Isha (ruler of Orissa), 1592 | Ramachandradeva, the Bhoi dynasty ruler of Khurda | Revolt was by local Muslim rulers who desecrated the images.[20] |

| 7 | Mirza Khurum, the commander of Islam Khan I, the Nawab of Bengal, 1601 | Purushottamadeva of Bhoi Dynasty | Image moved to Kapileswarpur village by boat through the river Bhargavi and kept in the Panchamukhi Gosani temple. Thereafter, the deities were kept in Dobandha—Pentha.[20] |

| 8 | Hasim Khan, the Subedar of Orissa, 1608 | Purushottam Deva, the King of Khurda | Images shifted to the Gopal temple at Khurda and brought back in 1608.[20] |

| 9 | Kesodasmaru, 1610 | Purusottamdeva, the king of Khurda | Images kept at the Gundicha Temple and brought back to Puri after eight months.[20] |

| 10 | Kalyan Malla, 1611 | Purushottamadeva, the King of Khurda | Images moved to 'Mahisanasi' also known as'Brahmapura' or 'Chakanasi' in the Chilika Lake where they remained for one year.[21] |

| 11 | Kalyan Malla, 1612 | Paiks of Purushottamadeva, the King of Khurda | Images placed on a fleet of boats at Gurubai Gada and hidden under the 'Lotani Baragachha' or Banyan tree) and then at 'Dadhibaman Temple'.[22] |

| 12 | Mukarram Khan, 1617 | Purushottama Deva, the King of Khurda | Images moved to the Bankanidhi temple, Gobapadar and brought back to Puri in 1620.[22] |

| 13 | Mirza Ahmad Beg, 1621 | Narasingha Deva | Images shifted to 'Andharigada' in the mouth of the river Shalia across the Chilika Lake. Moved back to Puri in 1624.[23] |

| 14 | Amir Mutaquad Khan alias Mirza Makki, 1645 | Narasingha Deva and Gangadhar | Not known.[24] |

| 15 | Amir Fateh Khan, 1647 | Not known | Not known[24] |

| 16 | Ekram Khan and Mastram Khan on behalf of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, 1692 | Divyasingha Deva, the king of Khurda | Images moved to 'Maa Bhagabati Temple' and then to Bada Hantuada in Banpur across the Chilika Lake, and finally brought back to Puri in 1699.[24] |

| 17 | Muhammad Taqi Khan, 1731 and 1733 | Birakishore Deva and Birakishore Deva of Athagada | Images moved to Hariswar in Banpur, Chikili in Khalikote, Rumagarh in Kodala, Athagada in Ganjam and lastly to Marda in Kodala. Shifted back to Puri after 2.5 years.[24] |

| 18 | Followers of Mahima Dharma, 1881 | Birakishore Deva and Birakishore Deva of Athagada | Images burnt in the streets. [25] |

Puri is the site of the Govardhana Matha, one of the four cardinal institutions established by Adi Shankaracharya, when he visited Puri in 810 AD, and since then it has become an important dham (divine centre) for the Hindus; the others being those at Sringeri, Dwarka and Jyotirmath. The Matha (monastery of various Hindu sects) is headed by Jagatguru Shankarachrya. It is a local belief about these dhams that Vishnu takes his dinner at Puri, has his bath at Rameshwaram, spends the night at Dwarka and does penance at Badrinath.[12][26]

In the 16th century, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu of Bengal established the Bhakti movements of India, now known by the name the Hare Krishna movement. He spent many years as a devotee of Jagannatha at Puri; he is said to have merged with the deity.[27] There is also a matha of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu here known as Radhakanta Math.[12]

In the 17th century, for the sailors sailing on the east coast of India, the temple served as a landmark, being located in a plaza in the centre of the city, which they called the "White Pagoda" while the Konark Sun Temple, 60 kilometres (37 mi) away to the east of Puri, was known as the "Black Pagoda".[27]

The iconic representation of the images in the Jagannath temple is believed to be the forms derived from the worship made by the tribal groups of Sabaras belonging to northern Odisha. These images are replaced at regular intervals as the wood deteriorates. This replacement is a special event carried out ritualistically by special group of carpenters.[27]

The city has many other Mathas as well. The Emar Matha was founded by the Tamil Vaishnava saint Ramanujacharya in the 12th century AD. This Matha, which is now located in front of Simhadvara across the eastern corner of the Jagannath Temple, is reported to have been built in the 16th century during the reign of kings of Suryavamsi Gajapatis. The Matha was in the news on 25 February 2011 for the large cache of 522 silver slabs unearthed from a closed chamber.[28][29]

The British conquered Orissa in 1803, and, recognizing the importance of the Jagannath Temple in the life of the people of the state, they initially appointed an official to look after the temple's affairs and later declared the temple as part of a district.[14]

Modern history

editIn 1906, Sri Yukteswar, an exponent of Kriya Yoga and a resident of Puri, established an ashram, a spiritual training center, named "Karar Ashram"[30] in Puri. He died on 9 March 1936 and his body is buried in the garden of the ashram.[31][32]

The city is the site of the former summer residence of British Raj, the Raj Bhavan, built in 1913–14 during the era of governors.[33]

For the people of Puri, Jagannatha, visualized as Krishna, is synonymous with their city. They believe that Jagannatha looks after the welfare of the state. However, after the partial collapse of the Jagannath Temple (in the Amalaka part of the temple) on 14 June 1990, people became apprehensive and considered it a bad omen for Odisha. The replacement of the fallen stone by another of the same size and weight (7 tonnes (7.7 tons)), that could be done only in the early morning hours after the temple gates were opened, was done on 28 February 1991.[27]

Puri has been chosen as one of the heritage cities for the Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana scheme of the Indian Government. It is chosen as one of the 12 heritage cities with "focus on holistic development" to be implemented within 27 months by the end of March 2017.[34]

Non-Hindus are not permitted to enter the shrines but are allowed to view the temple and the proceedings from the roof of the Raghunandan library, located within the precincts of the temple, for a small donation.[35]

Geography and climate

editGeography

editPuri, located on the east coast of India on the Bay of Bengal, is in the centre of the Puri district. It is delimited by the Bay of Bengal on the southeast, the Mauza Sipaurubilla on the west, Mauza Gopinathpur in the north and Mauza Balukhand in the east. It is within the 67 kilometres (42 mi) coastal stretch of sandy beaches that extends between Chilika Lake and the south of Puri city. However, the administrative jurisdiction of the Puri Municipality extends over an area of 16.3268 square kilometres (6.3038 sq mi) spread over 30 wards, which includes a shore line of 5 kilometres (3.1 mi).[36]

Puri is in the coastal delta of the Mahanadi River on the shores of the Bay of Bengal. In the ancient days it was near to Sisupalgarh (also known as "Ashokan Tosali"). Then the land was drained by a tributary of the Bhargavi River, a branch of the Mahanadi River. This branch underwent a meandering course creating many arteries altering the estuary, and formed many sand hills. These sand hills could be cut through by the streams. Because of the sand hills, the Bhargavi River, flowing to the south of Puri, moved away towards the Chilika Lake. This shift also resulted in the creation of two lagoons, known as Sar and Samang, on the eastern and northern parts of Puri respectively. Sar lagoon has a length of 5 miles (8.0 km) in an east–west direction and a width of 2 miles (3.2 km) in north–south direction. The estuary of the Bhargavi River has a shallow depth of just 5 feet (1.5 m) and the process of siltation continues. According to a 15th-century Odia writer Saraladasa, the bed of the unnamed stream that flowed at the base of the Blue Mountain or Neelachal was filled up. Katakarajavamsa, a 16th-century chronicle (c.1600), attributes filling up of the bed of the river which flowed through the present Grand Road, as done during the reign of King Narasimha II (1278–1308) of Eastern Ganga dynasty.[37]

Climate

editAccording to the Köppen–Geiger climate classification system the climate of Puri is classified as Aw (Tropical savanna climate). The city has moderate and tropical climate. Humidity is fairly high throughout the year. The temperature during summer touches a maximum of 36 °C (97 °F) and during winter it is 17 °C (63 °F). The average annual rainfall is 1,337 millimetres (52.6 in) and the average annual temperature is 26.9 °C (80.4 °F). The weather data is given in the following table.[38][39][40]

| Climate data for Puri (1981–2010, extremes 1901–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.4 (92.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

40.0 (104.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

42.2 (108.0) |

44.2 (111.6) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.8 (98.2) |

39.1 (102.4) |

36.1 (97.0) |

34.2 (93.6) |

32.8 (91.0) |

44.2 (111.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.5 (81.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.3 (86.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 15.3 (0.60) |

20.7 (0.81) |

20.9 (0.82) |

24.9 (0.98) |

68.7 (2.70) |

178.1 (7.01) |

290.5 (11.44) |

361.0 (14.21) |

261.4 (10.29) |

168.9 (6.65) |

65.9 (2.59) |

10.7 (0.42) |

1,486.8 (58.54) |

| Average rainy days | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 8.5 | 11.5 | 14.1 | 10.3 | 7.0 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 62.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 71 | 76 | 81 | 84 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 81 | 74 | 66 | 64 | 78 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[39][40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editReligious Demographic in Puri Municipality (2011)[41]

According to the 2011 Census of India, Puri is an urban agglomeration governed by the Municipal Corporation in Odisha state, with a population of 200,564,[42] comprising 104,086 males, 96,478 females, and 18,471 children (under six years of age). The sex ratio is 927. The average literacy rate in the city is 88.03 percent (91.38 percent for males and 84.43 percent for females).

Religion

editThe overwhelming majority of the people in the city (98%) are Hindus, with a small Christian population.[41]

Language

editMajority of the people speaks Odia, followed by a large minority of Telugu speakers, with substantial number of Bengali and Hindi speakers.[44]

Administration

editThe Puri Municipality, Puri Konark Development Authority, Public Health Engineering Organisation and Orissa Water Supply Sewerage Board are some of the principal organisations that are devolved with the responsibility of providing for civic amenities such as water supply, sewerage, waste management, street lighting and infrastructure of roads. The major activity, which puts maximum pressure on these organisations, is the annual event of the Ratha Yatra held during June- July. According to the Puri Municipality more than a million people attend this event. Hence, development activities such as infrastructure and amenities to the pilgrims, apart from security, gets priority attention.[45]

The civic administration of Puri is the responsibility of the Puri Municipality. The municipality came into existence in 1864 in the name of the Puri Improvement Trust, which was converted into Puri Municipality in 1881. After India's independence in 1947, the Orissa Municipal Act (1950) was promulgated entrusting the administration of the city to the Puri Municipality. This body is represented by elected representatives with a Chairperson and councilors representing the 30 wards within the municipal limits.[46]

The electricity is provided by Tata Power Central Odisha Distribution Limited in the city and the entire district.[47]

Economy

editThe economy of Puri is dependent on tourism to the extent of about 80 percent. The temple is the focal point of the city and provides employment to the people of the town. Agricultural production of rice, ghee, vegetables and so forth of the region meet the large requirements of the temple. Many settlements around the town exclusively cater to the other religious requirements of the temple.[48] The temple administration employs 6,000 men to perform the rituals. The temple also provides economic sustenance to 20,000 people.[35] According to Colleen Taylor Sen, an author on food and travel, writing on the food culture of India, the temple kitchen has 400 cooks serving food to as many as 100,000 people.[49] According to J Mohapatra, Director, Ind Barath Power Infra Ltd (IBPIL), the kitchen is known as "a largest and biggest kitchen of the world."[50]

Culture and cityscape

editLandmarks

editJagannath Temple at Puri

editThe Jagannath Temple at Puri is one of the major Hindu temples built in the Kalinga style of architecture.[51] The temple tower, with a spire, rises to a height of 58 metres (190 ft), and a flag is unfurled above it, fixed over a wheel (chakra).[35][52]

The temple is built on an elevated platform (of about 420,000 square feet (39,000 m2) area),[53] 20 feet (6.1 m) above the adjacent area. The temple rises to a height of 214 feet (65 m) above the road level. The temple complex covers an area of 10.7 acres (4.3 ha).[45] There are four entry gates in four cardinal directions of the temple, each gate located at the central part of the walls. These gates are: the eastern gate called the Singhadwara (Lions Gate), the southern gate known as Ashwa Dwara (Horse Gate), the western gate called the Vyaghra Dwara (Tigers Gate) or the Khanja Gate, and the northern gate called the Hathi Dwara or (elephant gate). These four gates symbolize the four fundamental principles of Dharma (right conduct), Jnana (knowledge), Vairagya (renunciation) and Aishwarya (prosperity). The gates are crowned with pyramid shaped structures. There is a stone pillar in front of the Singhadwara, called the Aruna Stambha {Solar Pillar}, 11 metres (36 ft) in height with 16 faces, made of chlorite stone; at the top of the stamba an elegant statue of Aruṇa (Sun) in a prayer mode is mounted. This pillar was shifted from the Konarak Sun Temple.[54] The four gates are decorated with guardian statues in the form of lion, horse mounted men, tigers, and elephants in the name and order of the gates.[35] A pillar made of fossilized wood is used for placing lamps as offering. The Lion Gate (Singhadwara) is the main gate to the temple, which is guarded by two guardian deities Jaya and Vijaya.[53][54][55] The main gate is ascended through 22 steps known as Baisi Pahaca, which are revered, as it is believed to possess "spiritual animation". Children are made to roll down these steps, from top to bottom, to bring them spiritual happiness. After entering the temple, on the left side, there is a large kitchen where food is prepared in hygienic conditions in huge quantities; the kitchen is called as "the biggest hotel of the world".[53]

According to a legend King Indradyumma was directed by Jagannatha in a dream to build a temple for him which he did as directed. However, according to historical records the temple was started some time during the 12th century by King Chodaganga of the Eastern Ganga dynasty. It was completed by his descendant, Anangabhima Deva, in the 12th century. The wooden images of Jagannatha, Balabhadra and Subhadra were then deified here. The temple was under the control of the Hindu rulers up to 1558. Then, when Orissa was occupied by the Afghan Nawab of Bengal, it was brought under the control of the Afghan General Kalapahad. Following the defeat of the Afghan king by Raja Mansingh, the General of Mughal emperor Akbar, the temple became part of the Mughal empire till 1751. Subsequently, it was under the control of the Marathas till 1803. During the British Raj, the Puri Raja was entrusted with its management until 1947.[52]

The triad of images in the temple are of Jagannatha, personifying Krishna, Balabhadra, His older brother, and Subhadra, His younger sister. The images are made of neem wood in an unfinished form. The stumps of wood which form the images of the brothers have human arms, while that of Subhadra does not have any arms. The heads are large, painted and non-carved. The faces are marked with distinctive large circular eyes.[27]

The Pancha Tirtha of Puri

editHindus consider it essential to bathe in the Pancha Tirtha or the five sacred bathing spots of Puri, to complete a pilgrimage to Puri. The five sacred water bodies are the Indradyumana Tank, the Rohini Kunda, the Markandeya Tank, the Swetaganga Tank, and the Bay of Bengal also called the Mahodadhi, in Sanskrit 'Mahodadhi' means a "great ocean";[56] all are considered sacred bathing spots in the Swargadwara area.[57][58][59] These tanks have perennial sources of supply from rainfall and ground water.[60]

Gundicha Temple

editThe Gundicha Temple, known as the Garden House of Jagannatha, stands in the centre of a garden, bounded by compound walls on all sides. It lies at a distance of about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to the northeast of the Jagannath Temple. The two temples are located at the two ends of the Bada Danda (Grand Avenue), which is the pathway for the Ratha Yatra. According to a legend, Gundicha was the wife of King Indradyumna who originally built the Jagannath temple.[61]

The temple is built using light-grey sandstone, and, architecturally, it exemplifies typical Kalinga temple architecture in the Deula style. The complex comprises four components: vimana (tower structure containing the sanctum), jagamohana (assembly hall), nata-mandapa (festival hall) and bhoga-mandapa (hall of offerings). There is also a kitchen connected by a small passage. The temple is set within a garden, and is known as "God's Summer Garden Retreat" or garden house of Jagannatha. The entire complex, including the garden, is surrounded by a wall which measures 430 by 320 feet (131 m × 98 m) with height of 20 feet (6.1 m).[62]

Except for the 9-day Ratha Yatra, when the triad images are worshipped in the Gundicha Temple, otherwise it remains unoccupied for the rest of the year. Tourists can visit the temple after paying an entry fee. Foreigners (generally prohibited entry in the main temple) are allowed inside this temple during this period.[63] The temple is under the Jagannath Temple Administration, Puri, the governing body of the main temple. A small band of servitors maintain the temple.[62]

Swargadwar

editSwargadwar is the name given to the cremation ground or burning ghat which is located on the shores of the sea. Here thousands of dead bodies of Hindus brought from faraway places are cremated. It is a belief that the Chaitanya Mahaparabhu disappeared from this Swargadwar about 500 years back.[64]

Beach

editThe beach at Puri, known as the "Ballighai beach, at the mouth of Nunai River", is 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) away from the town and is fringed by casurina trees.[12] It has golden yellow sand. Sunrise and sunset are pleasant scenic attractions here.[65] Waves break in at the beach which is long and wide.[27]

District museum

editThe Puri district museum is located on the station road where the exhibits in display are the different types of garments worn by Jagannatha, local sculptures, patachitra (traditional, cloth-based scroll painting), ancient Palm-leaf manuscripts, and local craft work.[66]

Raghunandana library

editRaghunandana Library is located in the Emara Matha complex (opposite Simhadwara or lion gate, the main entrance gate). The Jagannatha Aitihasika Gavesana Samiti (Jagannatha Historical Centre) is also located here. The library houses ancient palm leaf manuscripts on Jagannatha, His cult and the history of the city.[66]

Festivals of Puri

editPuri witnesses 24 festivals every year, of which 13 are major. The most important of these is the Ratha Yatra, or the car festival, held in the June–July, which is attended by more than 1 million people.[67]

Ratha Yatra at Puri

editThe Jagannath Temple triad are normally worshipped in the sanctum of the temple at Puri, but once during the month of Asadha (rainy season of Orissa, usually in June or July), they are brought out on the Bada Danda (main street of Puri) and taken over a distance of (3 kilometres (1.9 mi)) to the Gundicha Temple[68] in huge chariots (ratha), allowing the public to have darśana (holy view). This festival is known as the Ratha Yatra, meaning the journey (yatra) of the chariots.[69] The yatra starts every year according to the Hindu calendar on the Asadha Sukla Dwitiya day, the second day of bright fortnight of Asadha (June–July).[70]

Historically, the ruling Ganga dynasty instituted the Ratha Yatra on the completion of the Jagannath Temple around 1150 AD. This festival was one of those Hindu festivals that was reported to the Western world very early.[71] Friar Odoric, in his account of 1321, reported how the people put the "idols" on chariots, and the King, the Queen and all the people drew them from the "church" with song and music.[72][73]

The Rathas are huge wooden structures provided with large wheels, which are built anew every year and are pulled by the devotees. The chariot for Jagannatha is about 45 feet (14 m) high and 35 square feet (3.3 m2) and takes about 2 months for its construction.[74] The chariot is mounted with 16 wheels, each of 7 feet (2.1 m) diameter. The carving in the front face of the chariot has four wooden horses drawn by Maruti. On its other three faces, the wooden carvings are of Rama, Surya and Vishnu. The chariot is known as Nandi Ghosha. The roof of the chariot is covered with yellow and red coloured cloth. The next chariot is of Balabhadra which is 44 feet (13 m) in height fitted with 14 wheels. The chariot is carved with Satyaki as the charioteer, roof covered in red and green coloured cloth, and the chariot is known as Taladhwaja. The carvings on this chariot include images of Narasimha and Rudra as Jagannatha's companions. The next chariot in the order is of Subhadra, which is 43 feet (13 m) in height supported on 12 wheels, roof covered in black and red colour cloth, and the chariot is known as Darpa Dalaan and the charioteer carved is Arjuna. Other images carved on the chariot are of Vana Durga, Tara Devi and Chandi Devi.[70][75] The artists and painters of Puri decorate the cars and paint flower petals and other designs on the wheels, the wood-carved charioteer and horses, and the inverted lotuses on the wall behind the throne.[69] The chariots of Jagannatha pulled during Ratha Yatra is the etymological origin of the English word Juggernaut.[76] The Ratha Yatra is also termed as the Shri Gundicha yatra and Ghosha yatra[70]

Chhera Panhara

editThe Chhera Panhara[77] (sweeping with water) is a significant ritual associated with the Ratha Yatra. During this ritual, the Gajapati King wears the outfit of a sweeper and sweeps all around the deities and chariots. The king cleans the road in front of the chariots with a gold-handled broom and sprinkles sandalwood water and powder. As per the custom, although the Gajapati King has been considered the most exalted person in the Kalingan kingdom, he still renders the menial service to Jagannatha. This ritual signifies that under the lordship of Jagannatha, there is no distinction between the powerful sovereign and the humblest devotee.[78]

Chandan Yatra

editThe Chandan Yatra festival held every year on Akshaya Tritiya day marks the commencement of the construction of the chariots of the Ratha Yatra. It also marks the celebration of the Hindu new year.[12]

Snana Yatra

editEvery year, on the Purnima day in the Hindu calendar month of Jyestha (June), the triad images of the Jagannath Temple are ceremonially bathed and decorated on the occasion of Snana Yatra. Water for the bath is taken in 108 pots from the Suna kuan (meaning: "golden well") located near the northern gate of the temple. Water is drawn from this well only once in a year for the sole purpose of the religious bath of the deities. After the bath the triad images are dressed in the fashion of the elephant god, Ganesha. Later, during the night, the original triad images are taken out in a procession back to the main temple but kept at a place known as Anasara pindi.[70] After this the Jhulan Yatra is performed when proxy images of the deities are taken out in a grand procession for 21 days, cruised over boats in the Narendra Tirtha tank.[12]

Anavasara or Anasara

editAnasara, a derivative of the Sanskrit word "Anabasara",[79] literally means vacation. Every year after the holy Snana Yatra, the triad images, without the Sudarshana Chakra, are taken to a secret altar named Anavasara Ghar (also known as Anasara pindi, 'pindi' is Oriya term meaning "platform" [79]) where they remain for the next fortnight of (Krishna paksha); devotees are not allowed to view these images. Instead, devotees go to the nearby Brahmagiri to see the Lord in the four-handed form of Alarnath, a depiction of Vishnu.[70][80] Devotees then get the first glimpse of the Lord only on the day before Ratha Yatra, which is called Navayouvana. It is a local belief that the gods suffer from fever after taking an elaborate ritual bath, and they are treated by the special servants, the Daitapatis, for 15 days. Daitapatis perform special nitis (rites) known as Netrotchhaba (a rite of painting the eyes of the triad). During this period cooked food is not offered to the deities.[81]

Naba Kalebara

editNaba Kalebara is one of the most grand events associated with the LJagannatha that takes place when one lunar month of Ashadha is followed by another of Ashadha called Adhika Masa (extra month). This can take place at an interval of 8, 12 or even 18 years. Literally meaning the "New Body" (Nava = New, Kalevar = Body) in Odia, the festival is witnessed by millions of people and the budget for this event generally exceeds $500,000. The event involves installation of new images in the temple and burial of the old ones in the temple premises at Koili Vaikuntha. During the Nabakalebara ceremony held during July 2015 the idols that were installed in the temple in 1996 were replaced by specially carved new images made of neem wood.[82][83] More than 3 million people are reported to have attended this festival.[84]

Suna Besha

editSuna Besha, ('Suna besh'in English translates to "gold dressing"[85]) also known as Raja or Rajadhiraja Bhesha [86] or Raja Bhesha, is an event when the triad images of the Jagannath Temple are adorned with gold jewelry. This event is observed five times in a year. It is commonly observed on Magha Purnima (January), Bahuda Ekadashi also known as Asadha Ekadashi (July), Dashahara (Bijayadashami) (October), Karthik Purnima (November), and Pousa Purnima (December).[87][88] One such Suna Bhesha event is observed on Bahuda Ekadashi during the Ratha Yatra on the chariots placed at the Simhadwar. The other four Beshas are observed inside the temple on the Ratna Singhasana (gem studded altar). On this occasion gold plates are decorated over the hands and feet of Jagannatha and Balabhadra; Jagannatha is also adorned with a Chakra (disc) made of gold on the right hand while a silver conch adorns the left hand. Balabhadra is decorated with a plough made of gold on the left hand while a golden mace adorns his right hand.[87]

Niladri Bije

editNiladri Bije, celebrated in the Hindu calendar month Asadha (June–July) on Trayodashi (13th day),[89] marks the end of the Ratha Yatra. The large wooden images of the triad of gods are taken out from the chariots and then carried to the sanctum sanctorum, swaying rhythmically; a ritual which is known as pahandi.[83]

Sahi yatra

editThe Sahi Yatra, considered the world's biggest open-air theatre,[90] is an annual event lasting 11 days; a traditional cultural theatre festival or folk drama which begins on Ram Navami and ends on Rama avishke (Sanskrit meaning : anointing). The festival includes plays depicting various scenes from the Ramayana. The residents of various localities, or Sahis, are entrusted the task of performing the drama at the street corners.[91]

Samudra Arati

editThe Samudra arati is a daily tradition started by the present Shankaracharya 9 years ago.[92] The daily practise includes prayer and fire offering to the sea at Swargadwar in Puri by disciples of the Govardhan Matha. On Paush Purnima of every year the Shankaracharya himself comes out to offer prayers to the sea.[92]

Arts and crafts

editSand art

editSand art is a special art form that is created on the beaches of Puri. The art form is attributed to Balaram Das, a poet who lived in the 14th century. Sculptures of various gods and famous people are now created in sand by amateur artists. These are temporary in nature as they get washed away by waves. This art form has gained international fame in recent years. One of the famed sand artists of Odisha is Sudarshan Patnaik. He established the Golden Sand Art Institute in 1995, in the open air on the shores of Bay of Bengal, to provide training to students interested in this art form.[93][91]

Appliqué art

editAppliqué art, which is a stitching-based craft unlike embroidery, was pioneered by Hatta Maharana of Pipili. It is widely used in Puri, both for decoration of the deities and for sale. Maharana's family members are employed as darjis or tailors or sebaks by the Maharaja of Puri. They prepare articles for decorating the deities in the temple for various festivals and religious ceremonies. The appliqué works are brightly colored and patterned fabric in the form of canopies, umbrellas, drapery, carry bags, flags, coverings of dummy horses and cows, and other household textiles; these are marketed in Puri. The cloth used is made in dark colours of red, black, yellow, green, blue and turquoise blue.[94]

Pattachitra

editPattachitra, one of the oldest forms of cloth-based scroll painting of the region, originally created for ritual use and as souvenirs for pilgrims to Puri, as well as other temples in Odisha.[95]

Cultural activities

editCultural activities, including the annual religious festivals, in Puri are: The Puri Beach Festival held from 5 to 9 November every year, and the Shreekshetra Utsav held from 20 December to 2 January every year. The cultural programs include unique sand art, display of local and traditional handicrafts and food festival.[96] In addition, cultural programs are held for two hours on every second Saturday of the month at the district Collector's Conference Hall near Sea Beach Police Station. Odissi dance, Odissi music and folk dances are part of this event.[96] Odissi dance is the cultural heritage of Puri. This dance form originated in Puri from the dances performed by Devadasis (Maharis) attached to the Jagannath Temple who performed dances in the Nata mandapa of the temple to please the deities. Though the devadasi practice has been discontinued, the dance form has become modern and classical and is widely popular; many of the Odissi virtuoso artists and gurus (teachers) are from Puri.[97] Some of the notable Odissi dancers are Kelucharan Mohapatra, Mayadhar Raut, Sonal Mansingh, and Sanjukta Panigrahi.[98]

Transport

editRoad

editEarlier, when roads did not exist, people used to walk or travel by animal-drawn vehicles or carriages along beaten tracks to reach Puri. Travel was by riverine craft along the Ganges up to Calcutta, and then on foot or by carriages. It was only during the Maratha rule that the Jagannath Sadak (Road) was built around 1790. The East India Company laid the rail track from Calcutta to Puri, which became operational in 1898.[99] Puri is now well-connected by rail, road and air services.[100]

Train

editA broad gauge railway line of the South Eastern Railways which connects Puri with Kolkata and Khorda Road is an important railway junction on this route. The rail distance is 499 kilometres (310 mi) from Kolkata and 468 kilometres (291 mi) from Vishakhapatnam. Road network includes NH 203 that links the city with Bhubaneswar, the state capital, situated about 60 kilometres (37 mi) away. NH 203 B connects the city with Satapada via Brahmagiri. Marine drive, which is part of NH 203 A, connects Puri with Konark. Puri railway station is among the top hundred booking stations of the Indian Railways.[101][102] Puri railway station is 1,321 kilometres (821 mi) away from New Delhi.[67][103]

Air

editA proposal was received from the State Government of Odisha for development of a Greenfield Airport at Puri to the Ministry of Civil Aviation seeking 'Site Clearance' approval under GFA Policy.[104]

Shree Jagannath International Airport is likely to be operational by 2024.[105]

Education

editSchools

edit- Bholanath Vidyapith

- Biswambhar Bidyapitha

- Blessed Sacrament High School Puri

- D.A.V Public School, Puri[106]

- Kendriya Vidyalaya, Puri[107]

- Puri Zilla School

Colleges and Universities

editNotable people

edit- Bidhu Bhusan Das - Academic and Vice Chancellor, DPI Odisha

- Gopabandhu Das – Social worker

- Nilakantha Das – Social activist

- Pankaj Charan Das – Odissi dancer

- Prabhat Nalini Das - pro Vice Chancellor, academician, feminist, Dean IIT Kanpur

- Gajapati Maharaja Dibyasingha Deb - Odia King

- Charles Garrett – Cricketer

- Chakhi Khuntia – Freedom fighter [108]

- Mayadhar Mansingh - Odia poet and writer

- Pinaki Misra - Politician

- Kelucharan Mohapatra – Odissi dancer

- Raghunath Mohapatra – Architect and sculptor

- Baisali Mohanty - ALC Global Fellow at University of Oxford, United Kingdom

- Rituraj Mohanty – Singer

- Sarat Kumar Mukhopadhyay - Poet, novelist

- Sudarshan Pattnaik – Sand Artist

- Jayee Rajguru - Freedom fighter

- Madhusudan Rao – Odia Poet

- Sudarshan Sahoo - Sculptor

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Who's Who". Puri District Administration. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Puri City". Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Chakraborty, Yogabrata (28 June 2023). "পুরীধাম ও জগন্নাথদেবের ব্রহ্মরূপ বৃত্তান্ত" [Puridham and the tale of lord Jagannath's legendary 'Bramharup']. dainikstatesmannews.com (in Bengali). Kolkata: Dainik Statesman (The Statesman Group). p. 4. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Development of Ramayana and Krishna Circuits". pib.gov.in. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. xxix.

- ^ a b Mahanti 2014, p. xxx.

- ^ a b Mahanti 2014, p. xxxi.

- ^ Glashoff, Klaus. "Sanskrit Dictionary for Spoken Sanskrit". Spokensanskrit.de. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Ananda 2015, p. 11.

- ^ "Jagannathyatra". Jagannathyatra. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Kapoor 2002, p. 5890.

- ^ Sadasivan 2000, p. 211.

- ^ a b c Ring, Salkin & Boda 1994, p. 699.

- ^ a b Dash 2011, p. 82.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. xliii7.

- ^ Dash 2011, p. 82–83.

- ^ a b c Dash 2011, p. 83.

- ^ Dash 2011, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Dash 2011, p. 85.

- ^ Dash 2011, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b Dash 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Dash 2011, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b c d Dash 2011, p. 88.

- ^ Dash 2011, p. 89.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. xxxii.

- ^ a b c d e f Ring, Salkin & Boda 1994, p. 697.

- ^ "Documentation format for Archaeological / Heritage Sites / Monuments" (PDF). Emar Matha, Puri town. Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Hidden treasure' worth Rs. 90 crores found in Puri's Emar Mutt". The Hindu. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Kriya Yoga Teaching & Meditation Centre | Karar Ashram". kararashram.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 248.

- ^ Davis 1997, p. 265.

- ^ "Raj Bhavan, Puri". Official website of rajbhavan. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana". HRIDAY National Project Management Unit National Institute of Urban Affairs. Archived from the original on 26 August 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Bindloss, Brown & Elliott 2007, p. 253.

- ^ Managers 2006, p. 1–2.

- ^ Starza 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. xxxiiii.

- ^ a b "Station: Puri Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 629–630. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M166. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b "C-01: Population by religious community". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Puri District Handbook 2011" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ 2011 census data censusindia.gov.in

- ^ "C-16 City: Population by mother tongue (town level)". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ a b Managers 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Managers 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Sharma, Vikash (19 September 2021). "'Irregularities' In Meter Installation By TPCODL: Puri Congress Stages Dharna, Admin Sets Up Committee". Odisha TV. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Managers 2006, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Sen 2004, p. 126.

- ^ Mohapatra 2013, p. 61.

- ^ "Temple Architecture". Culture Department, Government of Orissa. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Jagannath Temple, India – 7 wonders". 7wonders.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

The temple is divided into four chambers: Bhogmandir, Natamandir, Jagamohana and Deul

- ^ a b c "About Jagannath Temple". Official Website of Shree jagannath temple Administration. Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b Managers 2006, pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Temple information: Jagannath temple". Full Orissa. Archived from the original on 27 August 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Ravi, p. 230.

- ^ "Panch Tirtha of Puri". Shreekhetra. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Starza 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Madan1988, p. 161.

- ^ Managers 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Bansal 2012, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Mahapatra, Bhagaban. "Significance of Gundicha Temple in Car festival" (PDF). E-Magazine, Government of Orissa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Panda, Namita (22 June 2012). "Ready for the Trinity". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, pp. xl–xli.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Mahanti 2014, p. xli.

- ^ a b Managers 2006, p. 2.

- ^ "Bada Danda Puri Puri and Gundicha Temple Puri by Road, Distance Between Bada Danda Puri Puri and Gundicha Temple Puri, Distance by Road from Bada Danda Puri Puri and Gundicha Temple Puri with Travel Time, Gundicha Temple Puri Distance from Bada Danda Puri Puri, Driving Direction Calculator from bada danda puri puri and gundicha temple puri". Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ a b Das 1982, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e Barik, Sarmistha. "Festivals in Shri Jagannath Temple" (PDF). Government of Odisha. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Starza 1993, p. 133.

- ^ Starza 1993, p. 129.

- ^ Das 1982, p. 48.

- ^ Starza 1993, p. 16.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. Sarup & Sons. 1999. pp. 1076–77. ISBN 978-81-7625-064-1. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- ^ "Juggernaut-Definition and Meaning". Merriam Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Ramendra Kumar (26 July 2015). "Tales of Lord Jagannath: Chera Panhara, The Royal Sweeper". Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Karan, Jajati (4 July 2008). "Lord Jagannatha yatra to begin soon". IBN Live. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ a b Orissa Review. Home Department, Government of Orissa. 1980. p. 29. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- ^ "Temple of Alarnath". Official web site of Shreekshetra. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ "Festivals of Lord Sri Jagannath". nilachakra.org. 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

suffer from fever on the account of elaborate bath and for that they are kept in dietary provisions (No cooked food is served) and are nursed by the Daitas

- ^ "Puri gearing up for 2015 Nabakalebar". dailypioneer.com. 2011. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

Nabakalebar ritual of Lord Jagannath to be held in 2015,

- ^ a b "Nabakalebara festival comes to end with Niladri Bije". The Hindu. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- ^ "During the tight security of the millennium's first…". Gettyimages.ca. 7 July 2015. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ The Eastern Anthropologist. Ethnographic and Folk Culture Society. 1978. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. 103.

- ^ a b "Suna Bhesha(Ashadha/ June – July)". National Informatics center. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Arts of Asia. Arts of Asia. 2001. p. 84. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- ^ "Festivals of Lord Sri Jagannath". nilachakra.org. 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

NILADRI BIJE – Celebrated on 13th day of bright fortnight of Asadha.

- ^ Mahapatra, Prasanta (24 April 2013). "World's Biggest Open-Air Theatre Sahi Yatra Begins at Puri". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ a b Mahanti 2014, p. xl.

- ^ a b Sahu, Monideepa (6 March 2016). "The great fire". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Sand Arts". Government of Orissa. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Naik 1996, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Gadon, Elinor W. (February 2000). "Indian Art Worlds in Contention: Local, Regional and National Discourses on Orissan Patta Paintings. By Helle Bundgaard. Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Monograph Series, No. 80. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 1999. 247 pp. $45.00 (cloth)". The Journal of Asian Studies. 59 (1): 192–194. doi:10.2307/2658630. ISSN 1752-0401. JSTOR 2658630. S2CID 201436927. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ a b Mahanti 2014, p. Xxxviii.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. XL.

- ^ Maharaj, Guru Pandit Shyamal (2021). The Idea of Dance. Notion Press.com. p. 53. ISBN 9781685097950. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Mahanti 2014, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Mani, J.C. (2014). The Saga of Jagannatha and Badadeula at Puri. VIJ Books. p. 33. ISBN 9789382652458. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "Kolkata West Bengal and Puri By Road, Distance Between Kolkata West Bengal and Puri , Distance By Road From Kolkata West Bengal and Puri with Travel Time, Puri Distance from Kolkata West Bengal, Driving Direction Calculator from kolkata west bengal and puri". www.roaddistance.in. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Indian Railways Passenger Reservation Enquiry". Availability in trains for Top 100 Booking Stations of Indian Railways. IRFCA. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Silas, Sandeep (2005). Discover India by Rail. Sterlingpublishers.com. p. 75. ISBN 9788120729391. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "https://twitter.com/SwainShashank/status/1650517779160735744?s=20". Twitter. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "AAI technical team visits proposed site of Puri international airport". The Economic Times. 8 March 2022. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to DAV Public School, Puri". davpuri.in. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA PURI | KVS- Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan | Government of India". kvsangathan.nic.in. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography

edit- Ananda, Sri G. (2015). Empires of the Vedas Volume IV: The Kingdom of God. Art of Unity. ISBN 978-1-5078-9942-7.[permanent dead link]

- Bansal, Sunita Pant (1 April 2012). HIndu Pilgrimage: A journey through the holy places of hindus all over India. V&S Publishers. ISBN 978-93-5057-251-1.[permanent dead link]

- Das, Manoranjan (1982). The wooden horse: drama. Bookland International.

- Dash, Abhimanyu (July 2011). "Invasions on the Temple of Lord Jagannath, Puri" (PDF). Government of Odisha. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Bindloss, Joe; Brown, Lindsay; Elliott, Mark; Harding, Paul (2007). Northeast India. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74179-095-5.

- Davis, Roy Eugene (1 January 1997). Life Surrendered in God: The Philosophy and Practices of Kriya Yoga. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1495-0.

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- Kapoor, Subodh (2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7.

- Madan, T. N (1 January 1988). Way of Life: King, Householder, Renouncer : Essays in Honour of Louis Dumont. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0527-9.

- Managers, City (2006). "Puri City DevelopmentPlan 2006" (PDF). Puri Municipality:Government of Odisha. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- Mahanti, J C (2014). The Saga of Jagannatha and Badadeula at Puri (: Story of Lord Jagannatha and his Temple). Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-82652-45-8.

- Mohapatra, J (24 December 2013). Wellness In Indian Festivals & Rituals: Since the Supreme Divine is manifested in all the Gods, worship of any God is quite legitimate. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4828-1689-1.

- Naik, Shailaja D. (1 January 1996). Traditional Embroideries of India. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7024-731-9.

- Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; Boda, Sharon La (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- Sadasivan, S. N. (1 January 2000). A Social History of India. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7648-170-0.

- Starza, O. M. (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09673-6.

External links

edit- www.puri.nic.in – Official website of Puri District]

- Odisha Tourism

- OTDC