Indradyumna (Sanskrit: इन्द्रद्युम्न, romanized: Indradyumna) is the name of various kings featured in Hindu literature.

| Indradyumna | |

|---|---|

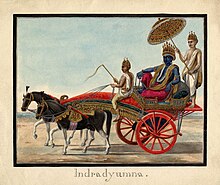

Watercolour painting on paper of Indradyumna seated in a carriage | |

| Texts | Mahabharata, Puranas |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents |

|

| Dynasty | Suryavamsha |

It is the name of a Pandya king featured in the Mahabharata and the Puranas, the son of King Sumati[1] of the Suryavamsha (Solar dynasty) and the grandson of Bharata. This king is best known for his legend of being rescued by Vishnu in the Gajendra Moksha[2] and the episode of his fall from heaven after the exhaustion of his virtue, and his subsequent return.

It is also the name of the king of the country of Avanti, sharing the same ancestry as the Pandya king. This Indradyumna is best known for the legend of his installation of the idols of the Jagannath temple of Puri,[3][4] featured prominently in the Puruṣottama-kṣetra-māhātmya section of the Skanda Purana.[5]

Etymology

editThe name is derived from the Sanskrit noun root Indra with verb morpheme “dyumn” (Root ‘dyu’ - Meaning ‘resplendent’), with the meaning of “One with the splendour like that of Indra."

Avanti Indradyumna

editThe Brahma Purana describes Indradyumna to be the pious king of Avanti, who lived during the Satya Yuga. Once, the king desired to see an image of the four-armed Vishnu at a holy site called Puruṣottama Kṣetra. At the request of Yama, before the king's arrival, Vishnu buried the image under the sand. The king, unable to find the image famed to be made of nīlamaṇi, decided to construct another temple with a new image of the deity. With the assistance of the kings of Utkala, Kalinga, and Kosala, he ordered the collection of rocks from the Vindhya mountains and finished the temple's construction. He received a divine dream from Vishnu regarding the procedure of installing the deity, following which he cut down a great tree with an axe in the seashore. After the installation of the images of Jagannatha, Balabhadra, Subhadra, and Sudarshana, the king celebrated the consecration of the site with the deities Vishnu and Vishvakarman, the divine artisan.[6]

The Skanda Purana's Puruṣottama-kṣetra-māhātmya includes many more details to this legend. Indradyumna is described to have sent his priest, Vidyapati, to locate the site of the image of Vishnu at the Puruṣottama Kṣetra. Vidyapati observes that the image was venerated by a member of the hill-folk named Vishvavasu. By the time Vidyapati returned to inform the king of the site, a great storm had buried the image under the sand. Despite his best attempts, the king was unable to locate the image. Upon the counsel of the sage divinity Narada, Indradyumna constructed a new temple, and performed a thousand ashvamedha yajnas at the site. A great tree floating in the sea was felled and used to create the three images of the temple, with the help of a carpenter, who was Vishnu in disguise. The king travelled to Brahmaloka to invite Brahma to inaugurate the temple. With the passage of time, a king named Gala claimed to have been the temple's real architect, but with the return of Indradyumna to earth, he withdrew this claim. After Brahma had inaugurated the temple, Indradyumna returned to Brahmaloka, entrusting the upkeep of the site to Gala.[7]

According to another legend, after the death of Krishna, his body was cremated, and his ashes were placed in a box. Vishnu requested Indradyumna to ask Vishvakarman to mould an image from this sacred relic. Vishvakarman agreed to perform this task, on the condition that he was left undisturbed until the completion of the image. After an impatient Indradyumna visited the site to check its progress after fifteen years had passed, the furious Vishvakarman departed, leaving the image incomplete. Brahma offered his own additions to the image and consecrated it as its chief priest.[8]

Pandya Indradyumna

editThe Bhagavata Purana, Canto 8, describes Indradyumna to be a saintly Vaishnava king, belonging to the lineage of Svayambhuva Manu, the ruler of the Pandyanadu country . He abdicated his throne in favour of his children when he grew old, and started to engage in a penance in the Malaya mountain. The sage Agastya came across the king when he was immersed in meditation, and was hence ignored. Angered, Agastya cursed the stubborn king to be reborn as an elephant. At Indradyumna's request, Agastya offered the following clause to the curse: The king would be liberated from his curse when he was offered salvation by Vishnu himself. Accordingly, Indradyumna was reborn as Gajendra, the king of the elephants.[9] Due to the piety of Indradyumna, Gajendra retained all the memories of its previous birth. Gajendra roamed about in a forest for various years with a herd of wild elephants, finally arriving at Mount Trikūṭa. When it arrived there at the banks of a lake, it was attacked by a makara, or a crocodile, that caught hold of its hind leg. This crocodile was the rebirth of a gandharva named Hūhū, cursed for carousing with apsaras by Sage Devala. Neither of the creatures gave in during their struggle for a thousand years. Vishnu then appeared to the site upon Garuda, and Gajendra raised its trunk and cried out his name in recognition. The deity severed the head of the crocodile with his discus and saved his devotee, lifting the curse, and offering Indradyumna a place in his abode of Vaikuntha.[10][11] The tale of Gajendra is often symbolically interpreted for its religious themes, with Gajendra as the man, Huhu as sins, and the muddy water of the lake as samsara.

The Mahabharata narrates another legend of this Indradyumna. After the virtue that he had accumulated was exhausted, the king fell from heaven to the earth. He was told that he would be allowed to return if someone could recall his good deeds that had gained him great merit. He visited Sage Markandeya, who failed to recognise him. Upon asking the sage if he knew anyone who had lived longer than him, the former directed him to Prāvīrakarṇa, an owl that dwelt in the Himalayas. The owl also did not remember him, and directed the king and the sage to Nāḍījaṃgha, a stork that was older than both, living in a lake named Indradyumna. The stork did know him, and directed the king to Akupara, a tortoise that lived within the same lake. Akupara immediately recognised the king, informing the sage of his great generosity and the ritual sacrifices he had conducted. The tortoise informed them that the very lake lent its name to the king, having been created by the passage of cows that had been gifted to the Brahmanas who had performed his rituals. Hearing this, the sage Markandeya restored his place in heaven, and in some accounts, a golden chariot arrived for his departure.[12][13][14]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Wilson, Horace Hayman (1877). The Vishńu Puráńa: A System of Hindu Mythology and Tradition Translated from the Original Sanskrit and Illustrated by Notes... Trübner & Company. p. 70. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Krishna, Nanditha (2014-05-01). Sacred Animals of India. Penguin UK. p. 170. ISBN 978-81-8475-182-6. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Dowson, John (1888). A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature. Robarts – University of Toronto. London : Trübner. p. 127.

- ^ Chakraborty, Yogabrata (28 June 2023). "পুরীধাম ও জগন্নাথদেবের ব্রহ্মরূপ বৃত্তান্ত" [Puridham and the tale of lord Jagannath's legendary 'Bramharup']. dainikstatesmannews.com (in Bengali). Kolkata: Dainik Statesman (The Statesman Group). p. 4. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Books, Kausiki (2021-10-24). Skanda Purana: Vaishnava Khanda: Purushottama Kshetra Mahatmya: English Translation only without Slokas. Kausiki Books. p. 249. Archived from the original on 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Parmeshwaranand, Swami (2001). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas. Sarup & Sons. p. 320. ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3. Archived from the original on 2023-03-08. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Parmeshwaranand, Swami (2001). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas. Sarup & Sons. p. 322. ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3. Archived from the original on 2023-03-08. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Walker, Benjamin (2019-04-09). Hindu World: An Encyclopedic Survey of Hinduism. In Two Volumes. Volume I A-L. Routledge. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-429-62465-0.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2014-04-18). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin UK. p. 186. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9.

- ^ Mani, Vettam (2015-01-01). Puranic Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Work with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 328–329. ISBN 978-81-208-0597-2.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (1993-01-01). Purāṇa Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. SUNY Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-7914-1381-4.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (2019-01-28). "Story of Indradyumna". www.wisdomlib.org. Archived from the original on 2023-01-14. Retrieved 2023-01-14.

- ^ Valmiki; Vyasa (2018-05-19). Delphi Collected Sanskrit Epics (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 459. ISBN 978-1-78656-128-2.

- ^ Silva, Jose Carlos Gomes da (2010-01-01). The Cult of Jagannatha: Myths and Rituals. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-81-208-3462-0.