Puniša Račić (Serbian Cyrillic: Пуниша Рачић; 12 July 1886 – 16 October 1944) was a Serb leader and People's Radical Party (NRS) politician. He assassinated Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) representatives Pavle Radić and Đuro Basariček and mortally wounded HSS leader Stjepan Radić in a shooting which took place on the floor of the Yugoslav parliament on 20 June 1928. He was tried and handed a 60-year sentence, which was immediately reduced to twenty years. He served most of his sentence under house arrest and was killed by the Yugoslav Partisans in October 1944.

Puniša Račić | |

|---|---|

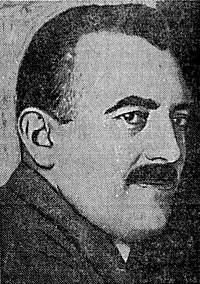

Puniša Račić, c. 1925 | |

| Member of Parliament in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes | |

| In office 27 September 1927 – 20 June 1928 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 July 1886 Slatina, Principality of Montenegro |

| Died | 16 October 1944 (aged 58) Belgrade, Democratic Federal Yugoslavia |

| Political party | People's Radical Party (NRS) |

Early life and political career

editPuniša Račić was born on 12 July 1886 in the village of Slatina, near Andrijevica, Principality of Montenegro.[1] He entered the employ of politician Nikola Pašić as a sixteen-year-old in 1902. Pašić regarded Račić as a son and encouraged his political ambitions. Račić became active in Serbian nationalist circles and claimed to have organized assassination attempts against King Ferdinand I of Bulgaria, King Constantine I of Greece and Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany. Following World War I, he earned a reputation for suppressing pro-Bulgarian movements in Macedonia.[2] He was one of many Chetnik leaders who formed Serbian cultural societies in the region.[3] On 27 September 1927,[4] he was elected to the parliament of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as a representative of the People's Radical Party (NRS).[5]

Račić is reported to have had connections with the ruling Karađorđević dynasty.[6] He was the leader of the Association of Serbian Chetniks "Petar Mrkonjić" – For King and Fatherland until 1928.[5] The movement was established following a split in the Chetniks in 1924 and built up a vast network across Bosnia and Herzegovina in the ensuing years. It maintained a close relationship with the Serbian National Youth (Serbian: Srpska nacionalna omladina, SRNAO).[7]

Parliament shooting

editOn 19 June 1928, Račić and twenty-three of his colleagues requested that Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) leader Stjepan Radić be examined by doctors to determine if he was mentally ill and, if it was discovered that he was not, that he be punished to the maximum extent for describing several Serbian ministers as "plunderers", "bandits" and "outlaws" and thus violating the parliament's rules of procedure.[8] At that day's session of parliament, Račić and fellow Serbian radical Toma Popović shouted: "Heads are going to roll here and until someone kills Stjepan Radić there can be no peace."[9] The atmosphere that day prompted Radić to remark that "a psychological mood for murder" was being created.[10] Several individuals in Serbia had made death threats against Radić in the preceding days. The Croatian People's Party (Croatian: Hrvatska pučka stranka, HPS), which stood opposed to Radić's anti-Clericalism and pan-Slavic ideas, also called for his removal from public life.[6] Serbian newspapers such as Politika (Politics), Samouprava (Self-administration) and Jedinstvo (Unity) demonized Croat politicians, including Radić, and called for their murder.[11]

Out of caution, Radić was quieter than usual at the following evening's session of parliament.[4] A verbal confrontation erupted that night when HSS deputy Ivan Pernar shouted insults at several Serbian politicians, questioning their wartime record and suggesting they were responsible for committing atrocities.[9] Croatian politician Lubomir Maštović then made a speech protesting how the death threats against Radić made by Popović and Račić the previous day had gone unpunished by the president of the Assembly, Ninko Perić. Popović responded by saying "...if Stjepan Radić, who shames the Croatian people, further continues with his insults, I guarantee that his head will fall."[12] The opposition benches reacted by shouting insults and death threats at the NRS party deputies, who responded in similar fashion. Perić ordered a five-minute recess and retreated to his private chamber, where he spoke with Račić.[13] Račić was given the floor when the session was resumed.[12] In his speech, he asserted that Serbian interests had never been in greater danger and stated that he would not refrain from using "other weapons, as need be, to defend the interests of Serbdom".[14] Opposing politicians, especially Pernar, responded by taunting Račić and shouting as he spoke. Račić demanded that Perić penalize those jeering at his speech.[12] Pernar then shouted "you plundered beys!", accusing Račić of looting Muslim homes in Macedonia. Seeing that Perić was not going to reprimand Pernar, Račić reached into his pocket and produced a handgun. The Minister of Justice, Milorad Vujičić, who was sitting behind the podium, grabbed Račić by the back while the former Minister of Religion, Obradović, seized his right shoulder. Račić pushed both men away and shot Pernar first.[13] He then turned his attention to Ivan Granđa and shot him.[11] He attempted to shoot Svetozar Pribićević just as HSS deputy Đuro Basariček jumped to the podium. Račić aimed at Pribićević but shot Basariček instead. He then shot Radić in the hand and stomach. Radić's nephew, Pavle, rushed to help his uncle.[12] Upon seeing him, Račić yelled "I was waiting for you!" and shot him at point-blank range.[13] He then fled the chamber.[14] Basariček and Radić's nephew died immediately. Pernar and Granđa were wounded but survived.[11] Radić was seriously wounded and was taken to hospital immediately, where he was visited by King Alexander I.[12]

Aftermath

editDemonstrations erupted in Zagreb at the news of the shooting. Five people were killed and many more were wounded in clashes with police in the ten days following the attack. Deputies from the HSS–Democratic Party coalition withdrew from the parliament in protest.[15] The shooting was the most significant political murder of Croat politicians during the inter-war period. It destroyed popular support for the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in Croatia.[6] On 4 August Vlada Ristović, the editor of Jedinstvo—one of the newspapers which had called for the murder of Radić and Pribićević—was assassinated by Josip Sunić, a member of the youth wing of the Croatian Party of Rights (Croatian: Hrvatska stranka prava, HSP).[16]

Radić was operated on shortly after he was shot and his surgeon predicted that he would recover. Within two months of the shooting, his condition deteriorated unexpectedly and he died on 8 August 1928.[17] Vladko Maček, Radić's successor as head of the HSS, suggested that diabetes had led to an infection which caused his heart to fail and suggested this as his cause of death.[12] A week before his death, Radić had alleged that Račić was only the executor of "a plot conceived of and agreed to in one part of the Radical [parliamentary] club" and stated that his shooting had likely occurred with the knowledge and approval of Perić and Prime Minister Velimir Vukićević.[18]

Račić was celebrated as a hero through much of Serbia.[19] He turned himself into the authorities shortly after the shooting[12] and was tried and sentenced to 60 years in prison. This was immediately reduced to 20 years.[19] His shooting of HSS deputies led to King Alexander suspending the Vidovdan Constitution on 6 January 1929, renaming the country to Yugoslavia and proclaiming a royal dictatorship.[20]

Later life and death

editRačić spent most of his sentence under house arrest in a comfortable villa, where he was attended by three servants and was free to enter and leave at will.[19] The leniency of his sentence likely came as a result of his connection with the Chetniks.[21] He was released from house arrest on 27 March 1941.[1] The Ustaše used Račić's shooting of Croatian deputies as one of their excuses for persecuting and massacring Serbs during World War II.[22] Račić was killed by the Yugoslav Partisans on 16 October 1944 during the liberation of Belgrade from the Axis powers.[1]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c Večernje novosti & 20 June 2013.

- ^ Glenny 2012, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Newman 2012, p. 155.

- ^ a b Ramet 2006, p. 71.

- ^ a b Tomasevich 1975, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Tomasevich 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Dragnich 1983, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Glenny 2012, p. 410.

- ^ Dragnich 1983, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Ramet 2006, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dragnich 1983, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Glenny 2012, p. 411.

- ^ a b Tanner 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 74.

- ^ Glenny 2012, p. 412.

- ^ Biondich 2000, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Despalatović 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Vucinich 1969, p. 18.

- ^ Singleton 1985, p. 150.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 406.

References

edit- Books

- Biondich, Mark (2000). Stjepan Radić, the Croat Peasant Party and the Politics of Mass Mobilization: 1904–1928. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8294-7.

- Despalatović, Elinor (2000). "The Roots of the War in Croatia". In Halpern, Joel Martin; Kideckel, David A. (eds.). Neighbors at War: Anthropological Perspectives on Yugoslav Ethnicity, Culture, and History. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-04435-4.

- Dragnich, Alex N. (1983). The First Yugoslavia: Search for a Viable Political System. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8179-7841-0.

- Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans: 1804–2012. London: Granta Books. ISBN 978-1-77089-273-6.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2017-2.

- Newman, John Paul (2012). Gerwarth, Robert; Horne, John (eds.). War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe After the Great War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968605-6.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09125-7.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1969). "Interwar Yugoslavia". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. OCLC 652337606.

- Websites

- "Kad Puca Ljuti Vasojević" [When a Mad Vasojević Fires]. Večernje novosti (in Serbian). 20 June 2013.

External links

edit- Parker, James Reid (1960). "The Archimandrite's Niece". In London, Ephraim (ed.). The World of Law; a Treasury of Great Writing about and in the Law, Short Stories, Plays, Essays, Accounts, Letters, Opinions, Pleas, Transcripts of Testimony; from Biblical Times to the Present. Vol. I. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 506 – via Internet Archive.