Puma (/ˈpjuːmə/ or /ˈpuːmə/) is a genus in the family Felidae whose only extant species is the cougar (also known as the puma, mountain lion, and panther,[2] among other names), and may also include several poorly known Old World fossil representatives (for example, Puma pardoides, or Owen's panther, a large, cougar-like cat of Eurasia's Pliocene).[3][4] In addition to these potential Old World fossils, a few New World fossil representatives are possible, such as Puma pumoides[5] and the two species of the so-called "American cheetah", currently classified under the genus Miracinonyx.[6]

| Puma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cougar (Puma concolor) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Puma Jardine, 1834 |

| Type species | |

| Felis concolor | |

| Species | |

| |

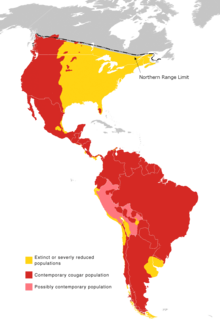

| Puma range. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

editPumas are large, secretive cats. They are also commonly known as cougars and mountain lions, and are able to reach larger sizes than some other "big" cat individuals. Despite their large size, they are more closely related to smaller feline species than to lions or leopards. The two subspecies[7] of pumas have similar characteristics but tend to vary in color and size. Pumas are the most adaptable felines in the Americas and are found in a variety of different habitats, unlike other cat species.[8]

Extant species

edit| Image | Scientific name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puma concolor | Cougar | Yukon in Canada to the southern Andes in Argentina and Chile |

Distribution and habitat

editMembers of the genus Puma are primarily found in the mountains of North and South America, where a majority of individuals can be found in rocky crags and pastures lower than the slopes grazing herbivores inhabit. Though they choose to inhabit those areas, they are highly adaptive and can be found in a large variety of habitats, including forests, tropical jungle, grasslands, and even arid desert regions. With the expansion of human settlements and land clearance, the cats are being pushed into smaller, more hostile areas. However, their high adaptability will likely allow them to avoid disappearing from the wild forever.[8]

Anatomy and appearance

editSubspecies of the genus Puma include cats that are the fourth-largest in the cat family. Adult males can reach around 7.9 feet (2.4 m) from nose to tip of tail, and a body weight typically between 115 and 220 pounds (52 and 100 kg). Females can reach around 6.7 feet (2.0 m) from nose to tail, and a body weight between 64 and 141 pounds (29 and 64 kg). They also have tails ranging from 25 to 37 inches (0.6 to 0.9 m) long. The heads of these cats are round, with erect ears. They have powerful forequarters, necks, and jaws which help grasp and hold prey. They have four retractable claws on their fore paws, and also their hind paws.

The majority of pumas are found in more mountainous regions, so they have a thick fur coat to help retain body heat during freezing winters. Depending on subspecies and the location of their habitat, the puma's fur varies in color from brown-yellow to grey-red. Individuals that live in colder climates have coats that are more grey than individuals living in warmer climates with a more red color to their coat. Pumas are incredibly strong and fast predators with long bodies and powerful short legs. The hindlimbs are larger and stronger than the forelimbs, enabling them to be great leapers. They are able to leap as high as 18 feet (5 m) into the air and as far as 40 to 45 feet (12 to 14 m) horizontally. They can reach speeds of up to 50 miles per hour (80 km/h), as they are adapted to perform powerful sprints in order to catch their prey.[8]

Behavior and lifestyle

editMembers of the genus live solitarily, with the exception of the time cubs spend with their mothers. Individuals cover a large home range searching for food, covering a distance around 80 mi2 during the summers and 40 mi2 during the winters. They are able to hunt at night just as effectively as they can during the day. Members of the genus are also known to make a variety of different sounds, particularly used when warning another individual away from their territory or during the mating season when looking for a mate.[8]

A study released in 2017 suggests that pumas have a secret social life only recently captured on film. They were seen sharing their food kills with other nearby pumas. They share many social patterns with more gregarious species such as chimpanzees.[9]

Diet

editMembers of this genus are large and powerful carnivores. The majority of their diet includes small animals such as rodents, birds, fish, and rabbits. Larger individuals are able to catch larger prey such as bighorn sheep, deer, guanaco, mountain goats, raccoons, and coati. They occasionally take livestock in areas with high populations of them.[8]

Reproduction and life cycles

editBreeding season normally occurs between December and March, with a three-month (91 days) gestation period resulting in a litter size up to six kittens. After mating, male and female part ways; the male continues on to mate with other females for the duration of the mating season, while the female cares for the kittens on her own. Like most other felines, kittens are born blind and remain completely helpless for about 2 weeks until their eyes open. Kittens are born with spots and eventually lose all of them as they reach adulthood. The spots allow the kittens to hide better from predators. Kittens are able to eat solid food when they reach 2–3 months of age, and remain with their mother for about a year. The life expectancy of individuals in the wild averages 12 years, but can reach up to 25 years in captivity.[8]

Conservation

editAlthough they have been pushed into smaller habitats by human settlement expansion, members of the genus have been designated least-concern species by the IUCN, indicating low risk of becoming extinct in their natural environments in the near future. This is due to their high adaptiveness to changing habitat conditions. In fact, many feel the pumas' ability to adapt to different environments explains their current numbers.[8] However, in many large metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, California, pumas' habitats have been fragmented by urban development and massive freeways. These barriers have made it nearly impossible for populations of mountain lions in specific areas of mountain ranges to reach one another to breed and increase genetic diversity. While populations remain, the proportion of kittens that are inbred is rising every year. This poses a threat to these already-reduced communities of mountain lions that are forced to adapt quickly to ever-shrinking habitats and increasingly frequent run-ins with humans. Many researchers from the National Park Service are using their findings to propose ideas to cities like Los Angeles, which harbors large populations of urban wildlife, to increase conservation efforts in areas on both sides of freeways, and begin the process of building wildlife crossings for wildlife to safely cross freeways.[10]

See also

edit- Path of the Puma: The Remarkable Resilience of the Mountain Lion

- Florida panther

- Jaguarundi, formerly considered to belong to the Puma genus

References

edit- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 544–545. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ California wildlife get their own highway crossing http://www.npr.org/transcripts/1095750186

- ^ Hemmer, H. (1965). Studien an "Panthera" schaubi Viret aus dem Villafranchien von Saint-Vallier (Drôme). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 122, 324–336.

- ^ Hemmer, H., Kahlike, R.-D. & Vekua, A. K. (2004). The Old World puma Puma pardoides (Owen, 1846) (Carnivora: Felidae) in the Lower Villafranchian (Upper Pliocene) of Kvabebi (East Georgia, Transcaucasia) and its evolutionary and biogeographical significance. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 233, 197–233.

- ^ Chimento, Nicolas Roberto, Maria Rosa Derguy, and Helmut Hemmer. "Puma (Herpailurus) pumoides (Castellanos, 1958)(Mammalia, Felidae) del Plioceno de Argentina." Serie Correlación Geológica 30.2 (2015).

- ^ Barnett, Ross; Barnes, Ian; Phillips, Matthew J.; Martin, Larry D.; Harington, C. Richard; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Cooper, Alan (2005-08-09). "Evolution of the extinct Sabretooths and the American cheetah-like cat". Current Biology. 15 (15): R589 – R590. Bibcode:2005CBio...15.R589B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.052. PMID 16085477. S2CID 17665121.

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 33–34. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Puma (Felis concolor)". Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Palmieri, Tim (2017-10-12). "The Secret Social Live of a Solitary Puma". Scientific American. Retrieved 2017-10-12.

- ^ Ernest, Holly B.; Wayne, Robert K.; Dalbeck, Lisa; Sikich, Jeffrey A.; Pollinger, John P.; Serieys, Laurel E. K.; Riley, Seth P. D. (2014-09-08). "Individual Behaviors Dominate the Dynamics of an Urban Mountain Lion Population Isolated by Roads". Current Biology. 24 (17): 1989–1994. Bibcode:2014CBio...24.1989R. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.029. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 25131676.