In baseball, a pull hitter is a batter who predominately hits the ball to the side of the field from which they bat. They are also known as a puller.

Definition

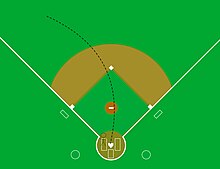

editA right-handed hitter stands on the left side of home plate and "pulls" the ball by sending it to the left side of the diamond. If the ball goes to the right side from a right-handed hitter, it has gone to the "opposite field". Players who rarely hit to the opposite field or the middle are called dead pull hitters. In general, pullers are meeting the ball earlier at the plate.[1]: 674

History

editBaseball lexicographer Paul Dickson recorded a usage of "pull hitter" in a 1925 column by Chilly Doyle in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, "The Pirate catcher (Earl Smith) is one of the league's 'pull' hitters; that is, Earl, a lefthand batter of the slugging type, smashes most of his wallops to rightfield."[2] The term was common by 1928 when Babe Ruth used it in Babe Ruth's Own Book of Baseball. In a section on "Correcting Batting Faults", he wrote, "Most fellows who can't hit curve balls are chaps who stride out of line or 'pull away' from the ball. Most batters who have trouble with slow ball pitching are 'pull' hitters. That is, they are meeting the ball 'out front.'"[3]: 164

Ted Williams wrote, "the ideal hit is a pulled ball 380 feet because that's a home run in most parks in the big leagues".[4] Charley Lau explained, "the best pitch to pull is one thrown on the inner half of the plate", i.e. the side closest to the hitter.[5] Rod Carew pointed out that trying to pull the ball reduces the hitting area by at least half.[6]

The ability to hit the ball to anywhere on the field is an extremely valuable skill. Some of the sport's best hitters will pull inside pitches and hit outside pitches to the opposite field.[7]: 44 Opposite field hitting is less often referred to as "pushing" the ball.[3]: 187 [1]: 677

Shifting

editIt is common for managers to implement the defensive tactic known as "shifting" for pull hitters. Players are moved to the side of the field where the pulled hit is likely to come. In 1923, defenses regularly shifted for Cy Williams, and throughout his career, Ted Williams faced the shift.[8]

For a left-handed power hitter like Harold Baines, a full "shift" moves the third baseman to the shortstop's normal position. The shortstop shifts to shallow right field between the first and second basemen. The outfielders will also shift towards the right side of the field. Analysts found that when the shift is on, pitchers also tend to throw more to the inside to encourage pull hits.[9]

As Sabermetrics developed, teams had more accurate information about batting tendencies, and they deployed the shift more frequently. In 2010, teams shifted 3,323 times. By 2017, the league was shifting 33,218 times a season.[10] In 2023, Major League Baseball essentially banned the full shift by requiring two infielders on either side of second base before each pitch.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Dickson, Paul. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd edition. WW Norton, 2009.

- ^ "Pull Hitter — Baseball Dictionary". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved 2024-10-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Ruth, George Herman. Babe Ruth's Own Book of Baseball. G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1928.

- ^ Williams, Ted., Underwood, John. The Science of Hitting. India: Touchstone, 1986. 41–2.

- ^ Lau, Charley, and Jeffrey Flanagan. Lau's Laws on Hitting. Addax Publishing Group, 2000. 18.

- ^ Carew, Rod and Frank Pace, Armen Keteyian. (2012). Rod Carew's Hit to Win: Batting Tips and Techniques from a Baseball Hall of Famer. MVP Books, 2012. 81.

- ^ Suzuki, Ichiro, and Jim Rosenthal. Ichiro's Art of Playing Baseball: Learn How to Hit, Steal, and Field Like an All-Star. St. Martin's Press, 2006.

- ^ Pavitt, Charlie. "Plummeting Batting Averages Are Due to Far More Than Infield Shifting, Part One: Fielding and Batting Strategy", Baseball Research Journal. Spring 2024.

- ^ Carleton, Russell A. “The Walk Penalty and the Death of the Shift.” Baseball Prospectus. August 19, 2020.

- ^ Greenberg, Neil (2018). "MLB's Opening Day featured unconventional lineups and bizarre defensive shifts: Analytics continue to leave its mark on Major League Baseball". The Washington Post. ProQuest 2019974930. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Scott (September 22, 2022). "M.L.B. Bans the Shift and Adds a Pitch Clock for 2023". The New York Times. Retrieved March 22, 2023.