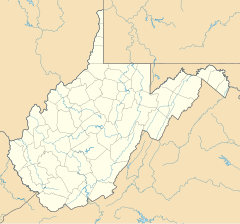

Project Greek Island (previously code-named "Project Casper"[1]) was a United States government continuity program located at the Greenbrier hotel in West Virginia.[2] The facility was decommissioned in 1992 after the program was exposed by The Washington Post. It is now known as the Greenbrier Bunker.

| Project Greek Island | |

|---|---|

The North Entrance of The Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. | |

| Type | Government continuity program |

| Location | 37°47′4.4″N 80°18′31.9″W / 37.784556°N 80.308861°W |

| Outcome | Decommissioned |

Construction

editIn the late 1950s, the United States government approached The Greenbrier resort and sought its assistance in creating a secret emergency relocation center to house the United States Congress due to the Cuban revolution and soon after the Cuban Missile Crisis. The classified, underground facility was built at the same time as the West Virginia Wing, an above-ground addition to the hotel, from 1959 to 1962.[3] For 30 years, The Greenbrier owners maintained an agreement with the federal government that, in the event of an international crisis, the entire resort property would be converted to government use, specifically as the emergency location for the legislative branch.[4]

The project used a cut-and-cover style construction method for the creation of the bunker,[3] where material, known as spoil, is removed from the surface and carried away from the site to create a space in which the bunker is constructed.[citation needed] In the case of the Project Greek Island Bunker, the spoil was used in the expansion of a 9-hole golf course and as fill material in a runway extension project at the local municipal airfield. This prevented detection of the project.[citation needed]

Facilities

editThe underground facility contained a dormitory, kitchen, hospital, and a broadcast center for members of Congress. The broadcast center had changeable seasonal backdrops to allow it to appear as if members of Congress were broadcasting from Washington, D.C.[citation needed] A 100-foot (30 m) radio tower was installed 4.5 miles (7.2 km) away for these broadcasts. The largest room is "The Exhibit Hall", 89 by 186 feet (27 by 57 m) beneath a ceiling nearly 20 feet (6.1 m) high and supported by 18 support columns. Adjoining it are two smaller auditoriums, one seating about 470 people, big enough to host the 435-member House of Representatives, and the smaller with a seating capacity of about 130, suitable as a temporary Senate chamber. The Exhibit Hall itself could be used for joint sessions of Congress.[3] The facility had a six-month supply of food, periodically refreshed.[6]

What was used by Greenbrier guests for business meetings was actually a disguised work area for members of Congress, complete with four hidden blast doors. Two of the doors were large enough to allow vehicles to enter. One weighed more than 28 short tons (25 t) and measured 12 feet 3 inches (3.73 m) wide and 15 feet (4.6 m) high. Another weighed more than 20 short tons (18 t). The doors were 19.5 inches (50 cm) thick.[3]

The two-foot-thick (0.61 m) walls of the bunker were made of reinforced concrete.[3]

Maintenance

editThe center was maintained by government workers posing as hotel employees, and operated under a dummy company named Forsythe Associates, based in Arlington, Virginia. The company's on-site employees maintained that their purpose was to maintain the hotel's 1100 televisions.[3] The company's first manager was John Londis, a former cryptographic expert with the Army Signal Corps. He had a top-secret security clearance and was stationed at the Pentagon.[3] Many of these same workers were later employed by the hotel and, for a time, gave guided tours. The complex is still maintained by The Greenbrier, and the facility remains much as it was in 1992, when the secret was revealed in the national press. While almost all of the furnishings were removed following the decommissioning of the bunker, the facility now has similar period furnishings to approximate what the bunker looked like while it was still in operation. Two of the original bunks in the dormitories remain.[4]

The bunker was designed to be incorporated into the public spaces of the hotel so as to not draw attention. Much of the bunker space was visible to the public, but went undetected for years, including The Exhibition Hall in the West Virginia Wing, which differs from other public spaces in the hotel due to large concrete columns present for reinforcing. Adjacent to the entrance of The Exhibition Hall is one of the original blast doors, which can now be seen openly, the original screen that once hid its presence removed.[4]

AT&T provided phone service for both The Greenbrier Hotel and the bunker. All calls placed from the bunker were routed through the hotel's switchboard to make it appear as if they originated from the hotel. The communications center in the bunker today contains representatives of three generations of telephone technology that were used.[4]

Although the bunker was kept stocked for 30 years, it was never actually used as an emergency location, even during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Decommissioning

editThe bunker's existence was not acknowledged until The Washington Post revealed it in a 1992 story;[3] immediately after the Post story, the government decommissioned the bunker.[citation needed]

The facility has since been renovated. It is used as a data storage facility for the private sector. It is once again featured as an attraction in which visitors can tour the now-declassified facilities, now known as the "Greenbrier Bunker".[2][9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Ozorak, Paul (2012). Underground Structures of the Cold War: The World Below. Casemate Publishers. p. 288. ISBN 9781783830817. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Tour The Greenbrier Bunker". PBS (website). Archived from the original on 2009-10-04. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gup, Ted (May 31, 1992). "The Ultimate Congressional Hideaway". The Washington Post. p. W11.

- ^ a b c d [citation needed]

- ^ "Estate Maps". The Greenbrier Concours. The Greenbrier. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "The Secret Bunker Congress Never Used". NPR (website). Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ^ Hall, Loretta (2004). Underground Buildings: More Than Meets the Eye. Quill Driver Books. p. 140. ISBN 9781884956270. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Hodge, Nathan; Weinberger, Sharon (2011). A Nuclear Family Vacation: Travels in the World of Atomic Weaponry. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 198. ISBN 9781608196692. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Wiener, Jon (2012). "The Graceland of Cold War Tourism: The Greenbrier Bunker". Dissent. 59 (3): 66–69. doi:10.1353/dss.2012.0069. S2CID 144991428.

External links

edit- The Bunker Archived 2019-10-24 at the Wayback Machine (official tourism website)

- Greenbriar Virtual Tour from the Cold War Civil Defense Museum