The Bengal Subah (Bengali: সুবাহ বাংলা. Persian: صوبه بنگاله.), also referred to as Mughal Bengal and Bengal State (after 1717), was the largest subdivision of Mughal India encompassing much of the Bengal region, which includes modern-day Bangladesh, the Indian state of West Bengal, and some parts of the present-day Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha between the 16th and 18th centuries. The state was established following the dissolution of the Bengal Sultanate, a major trading nation in the world, when the region was absorbed into the Mughal Empire. Bengal was the wealthiest region in the Indian subcontinent.

Bengal Province সুবাহ বাংলা صوبه بنگاله | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1576–1793 | |||||||||||||||

|

Flag of Nawab of Bengal after 1717 | |||||||||||||||

Map of the Bengal Subah in 1733 under the Nawabs of Bengal | |||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||||

| Subahdars/Nawab Nazims (see below) | |||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||||

| 12 July 1576 | |||||||||||||||

| 1571–1611 | |||||||||||||||

• Establishment of Jahangirnagar | 1608 | ||||||||||||||

| 1717 | |||||||||||||||

| April 1741–March 1751 | |||||||||||||||

| 23 June 1757 | |||||||||||||||

| 22–23 October 1764 | |||||||||||||||

| 16 August 1765 | |||||||||||||||

• Grant of administration and judiciary to Company | 1793 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1793 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Taka | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

Bengal Subah has been variously described the "Paradise of Nations"[6] and the "Golden Age of Bengal".[7] It alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.[8] The eastern part of Bengal was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding,[9] and it was a major exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpeter, and agricultural and industrial produce in the world.[10] The region was also the basis of the Anglo-Bengal War.[11]

By the 18th century, Bengal emerged as a semi-independent state, under the rule of the Nawabs of Bengal, who acted on Mughal sovereignty. It started to undergo proto-industrialization, making significant contributions to the first Industrial Revolution,[12][13][14][15] especially industrial textile manufacturing. In 1757 and 1764, the Company defeated the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey and the Battle of Buxar, and Bengal came under British influence. It was deindustrialized[12][13][14][10] after being conquered by the British East India Company. In 1765, Emperor Shah Alam II granted the office of the Diwani of Bengal (second-highest office in a province, included revenue rights) to the Company and the office of the Nizamat of Bengal (highest office, administrative and judicial rights) in 1793.[16] The Nawab of Bengal, who previously possessed both these offices, was now formally powerless and became a titular monarch.

History

editMughal Empire

editBengal's physical features gave it such a fertile soil, and a favourable climate that it became a terminus of a continent-wide process of Turko-Mongol conquest and migration, informs Prof. Richard Eaton.[17]

The Mughal absorption of Bengal began during the reign of the first Mughal emperor Babur. In 1529, Babur defeated Sultan Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah of the Bengal Sultanate during the Battle of Ghaghra. Babur later annexed parts of Bengal. His son and successor Humayun occupied the Bengali capital Gaur, where he stayed for six months.[18] Humayun was later forced to seek in refuge in Persia because of Sher Shah Suri's conquests. Sher Shah Suri briefly interrupted the reigns of both the Mughals and the Bengal Sultans.

The Mughal conquest of Bengal began with the victory of Akbar's army over Sultan of Bengal Daud Khan Karrani, the independent ruler of the province, at the Battle of Tukaroi on 3 March 1575. After the final defeat of Daud Karrani at the Battle of Rajmahal the following year,[19] Mughal Emperor Akbar announced the creation of Bengal as one of the original twelve Subahs (top-level provinces), bordering Bihar Subah and Orissa subah, as well as Burma.[citation needed] It took many years to overcome the resistance of ambitious and local chiefs. By a royal decree in November 1586, Akbar introduced uniform subah administration throughout the empire. However, in historian Tapan Raychaudhuri's view, "the consolidation of Mughal power in Bengal and the pacification of the province really began in 1594".[20]

Many of the chiefs subjugated by the Mughals, some of the Baro-Bhuyans in particular, were upstarts who grabbed territories during the transition from Afghan to Mughal rule, but others, such as the Rajas of Chandradwip, Malla, and Shushang, were older families who had ruled independently from time immemorial.[21] By the 17th century, the Mughals subdued opposition from the Baro-Bhuyans landlords, notably Isa Khan. Bengal was integrated into a powerful and prosperous empire; and shaped by imperial policies of pluralistic government. The Mughals built a new imperial metropolis in Dhaka from 1610, with well-developed fortifications, gardens, tombs, palaces and mosques. It served as the Mughal capital of Bengal for 75 years.[22] The city was renamed in honour of Emperor Jahangir.

The Mughal conquest of Chittagong in 1666 defeated the (Burmese) Kingdom of Arakan and reestablished Bengali control of the port city, which was renamed as Islamabad.[23] The Chittagong Hill Tracts frontier region was made a tributary state of Mughal Bengal and a treaty was signed with the Chakma Circle in 1713.[24]

Between 1576 and 1717, Bengal was ruled by a Mughal Subahdar (imperial governor). Members of the imperial family were often appointed to the position. Viceroy Prince Shah Shuja was the son of Emperor Shah Jahan. During the struggle for succession with his brothers Prince Aurangazeb, Prince Dara Shikoh and Prince Murad Baksh, Prince Shuja proclaimed himself as the Mughal Emperor in Bengal. He was eventually defeated by the armies of Aurangazeb. Shuja fled to the Kingdom of Arakan, where he and his family were killed on the orders of the King at Mrauk U. Shaista Khan was an influential viceroy during the reign of Aurangazeb. He consolidated Mughal control of eastern Bengal. Prince Muhammad Azam Shah, who served as one of Bengal's viceroys, was installed on the Mughal throne for four months in 1707. Viceroy Ibrahim Khan II gave permits to English and French traders for commercial activities in Bengal. The last viceroy Prince Azim-us-Shan gave permits for the establishment of the British East India Company's Fort William in Calcutta, the French East India Company's Fort Orleans in Chandernagore and the Dutch East India Company's fort in Chinsura. During Azim-us-Shan's tenure, his prime minister Murshid Quli Khan emerged as a powerful figure in Bengal. Khan gained control of imperial finances. Azim-us-Shan was transferred to Bihar. In 1717, the Mughal Court upgraded the prime minister's position to the hereditary Nawab of Bengal. Khan founded a new capital in Murshidabad. His descendants formed the Nasiri dynasty. Alivardi Khan founded a new dynasty in 1740. The Nawabs ruled over a territory which included Bengal proper, Bihar and Orissa.

Independent Nawabs of Bengal

editThe Nawab of Bengal[25][26][27][28] was the hereditary ruler of Bengal Subah in Mughal India. The Nawab of a princely state or autonomous province is comparable to the European title of Grand Duke. In the early 18th-century, the Nawab of Bengal was the de facto independent ruler of some part of Bengal and other parts were ruled by Bengal Rajas such as Bardhaman Raj, Cooch Behar State which constitute the modern-day sovereign country of Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal.[29][30][31] They are often referred to as the Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.[32] The nawabs were based in Murshidabad which was centrally located within Bengal. The nawabs continued to issue coins in the name of the Mughal Emperor. But for all practical purposes, the nawabs governed as independent monarchs.[citation needed] Under the early nawabs, Bengal became the financial backbone of the Mughal court, contributing more than half the funds that flowed into the imperial treasury in Delhi.[33]

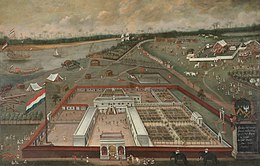

The Rajas of Bengal, Nawabs of Bengal oversaw a period of proto-industrialization. The Bengal-Bihar-Orissa triangle was a major production center for cotton muslin cloth, silk cloth, shipbuilding, gunpowder, saltpetre, and metalworks. Factories were set up in Murshidabad, Dhaka, Patna, Sonargaon, Chittagong, Rajshahi, Cossimbazar, Balasore, Pipeli, and Hugli among other cities, towns, and ports. The region became a base for the British East India Company, the French East India Company, the Danish East India Company, the Austrian East India Company, the Ostend Company, and the Dutch East India Company.

The British company eventually rivaled the authority of the Nawabs. In the aftermath of the siege of Calcutta in 1756, in which the Nawab's forces overran the main British base, the East India Company dispatched a fleet led by Robert Clive who defeated the last independent Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Mir Jafar was installed as the puppet Nawab. His successor Mir Qasim attempted in vain to dislodge the British. The defeat of Nawab Mir Qasim of Bengal, Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula of Oudh, and Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II at the Battle of Buxar in 1764 paved the way for British expansion across India. The South Indian Kingdom of Mysore led by Tipu Sultan overtook the Nawab of Bengal as the subcontinent's wealthiest monarchy; but this was short-lived and ended with the Anglo-Mysore War. The British then turned their sights on defeating the Marathas and Sikhs.

The Nawabs of Bengal entered into treaties with numerous European colonial powers, including joint-stock companies representing Britain, Austria, Denmark, France and the Netherlands.

Maratha raids

editThe resurgent Maratha Empire launched raids against Bengal in the 18th century, which further added to the decline of the Nawabs of Bengal. The Bengal Subah was met by a series of face to face confrontations by the Maratha Empire including the First Battle of Katwa, the Second Battle of Katwa, the Battle of Burdwan and the Battle of Rani Sarai where Nawab Alivardi Khan defeated the Marathas and repelled their attacks.[7][34] The Maratha raids lasted a decade from 1741 to early 1751.

The Marathas committed many atrocities across Bengal causing many to flee from West Bengal to East Bengal.[35] 400,000 civilian Bengalis were massacred by the Bargis (Maratha warriors) including textile weavers, silk winders, and mulberry cultivators[36][37] causing widespread economic devastation for the proto-industrializing textile-based economy of Bengal.[12][13][14][15] Many Bengalis were mutilated and contemporary accounts describe the scene of mass gang-rape against women.[38] Alivardi Khan the Nawab of Bengal fearing even worse devastation and destruction agreed to pay Rs. 1.2 million of tribute annually as the chauth of Bengal and Bihar to the Marathas, and the Marathas agreed not to invade Bengal again.

The expeditions, led by Raghuji Bhonsle of Nagpur, also established de facto Maratha control over Orissa, which was formally incorporated in the Maratha Empire in 1752.[39][40] The Nawab of Bengal also paid Rs. 3.2 million to the Marathas, towards the arrears of chauth for the preceding years.[41] The chauth was paid annually by the Nawab of Bengal to the Marathas up to 1758, until the British occupation of Bengal.[42]

British colonization

editBy the late-18th century, the British East India Company emerged as the foremost military power in the region, defeating the French-allied Siraj-ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, that was largely brought about by the betrayal of the Nawab's once trusted general Mir Jafar. The company gained administrative control over the Nawab's dominions, including Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. It gained the right to collect taxes on behalf of the Mughal Court after the Battle of Buxar in 1765. Bengal, Bihar and Orissa were made part of the Bengal Presidency and annexed into the British colonial empire in 1793. The Indian mutiny of 1857 formally ended the authority of the British East India Company, when the British Raj replaced Company rule in India.

Other European powers also carved out small colonies on the territory of Bengal, including the Dutch East India Company's Dutch Bengal settlements, the French colonial settlement in Chandernagore, the Danish colonial settlement in Serampore and the Habsburg monarchy Ostend Company settlement in Bankipur.

Military campaigns

editAccording to João de Barros, Bengal enjoyed military supremacy over Arakan and Tripura due to good artillery.[43] Its forces possessed notable large cannons. It was also a major exporter of gunpowder and saltpeter to Europe.[44][45] The Mughal Army built fortifications across the region, including Idrakpur Fort, Sonakanda Fort, Hajiganj Fort, Lalbagh Fort and Jangalbari Fort. The Mughals expelled Arakanese and Portuguese pirates from the northeastern coastline of the Bay of Bengal. Throughout the late medieval and early modern periods, Bengal was notable for its navy and shipbuilding. The following table covers a list of notable military engagements by Mughal Bengal:

| Conflict | Year(s) | Leader(s) | Enemy | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Tukaroi | 1575 | Akbar | Bengal Sultanate | Mughal (Bengal Subah) victory |

| Battle of Raj Mahal | 1576 | Khan Jahan I | Bengal Sultanate | Mughal (Bengal Subah) victory |

| Conquest of Bhati | 1576–1611 | Baro-Bhuyan | Mughal (Bengal Subah) victory | |

| Ahom-Mughal conflicts | 1615–1682 | Ahom kingdom | Mixed [46] | |

| Mughal-Arakan War | 1665–66 | Shaista Khan | Mughal (Bengal Subah) victory | |

| (Bengal Subah Dynasty Change) | 26 April 1740 |

|

Alivardi Khan | Alivardi Khan Victory |

| First Battle of Katwa | 1742 |

|

Maratha Confederacy | Bengali Victory |

| Battle of Birbhum | 1743 | Alivardi Khan

|

Maratha Confederacy | Bengali Victory |

| Second Battle of Katwa | December 1745 | Alivardi Khan | Maratha Confederacy | Bengali Victory |

| Second Battle of 'Midnapur' | 1746 | Alivardi Khan | Maratha Confederacy

|

Bengali Victory |

| Battle of Burdwan | January 1747 | Alivardi Khan | Maratha Confederacy | Bengali Victory |

| Battle of Rani Sarai | 1748 |

|

|

Bengali Victory |

| Siege of Calcutta | 20 June 1756 | British Empire | Bengali Victory | |

| Battle of Plassey | 1757 | Siraj-ud-Daulah | British Empire

|

British victory |

-

Daud Khan receives a robe from Munim Khan

-

Battle of Chittagong in 1666 between the Mughals and Arakanese

Architecture

editMughal architecture proliferated Bengal in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, with the earliest example being the Kherua Mosque in Bogra (1582).[34] They replaced the earlier sultanate-style of architecture. It was in Dhaka that the imperial style was most lavishly indulged in.[citation needed] Its Lalbagh Fort was an elaborately designed complex of gardens, fountains, a mosque, a tomb, an audience hall (Diwan-i-Khas) and a walled enclosure with gates. The Great Caravanserai and Shaista Khan Caravanserai in Dhaka were centres of commercial activities. Other monuments in the city include the Dhanmondi Shahi Eidgah (1640), the Sat Gambuj Mosque (c. 1664–76), the Shahbaz Khan Mosque (1679) and the Khan Mohammad Mridha Mosque (1704).[34] The city of Murshidabad also became a haven of Mughal architecture under the Nawabs of Bengal, with the Caravanserai Mosque (1723) being its most prominent monument.

In rural hinterlands, the indigenous Bengali Islamic style continued to flourish, blended with Mughal elements. One of the finest examples of this style is the Atiya Mosque in Tangail (1609).[34] Several masterpieces of terracotta Hindu temple architecture were also created during this period. Notable examples include the Kantajew Temple (1704) and the temples of Bishnupur (1600–1729).

Art

editAn authentic Bengali art was reflected in the muslin fabric of Jamdani (meaning "flower" in Persian). The making of Jamdani was pioneered by Persian weavers. The art passed to the hands of Bengali Muslim weavers known as juhulas. The artisan industry was historically based around the city of Dhaka. The city had over 80,000 weavers. Jamdanis traditionally employ geometric designs in floral shapes. Its motifs are often similar to those in Iranian textile art (buta motif) and Western textile art (paisley). Dhaka's jamdanis enjoyed a loyal following and received imperial patronage from the Mughal court in Delhi and the Nawabs of Bengal.[49][10]

A provincial Bengali style of Mughal painting flourished in Murshidabad during the 18th century. Scroll painting and ivory sculptures were also prevalent.

-

Murshidabad-style painting of a woman playing a rudra veena

-

Scroll painting of a Ghazi riding a Bengal tiger

Demographics

editPopulation

editBengal's population is estimated to have been 30 million prior to the Great Bengal famine of 1770, which reduced it by as much as a third.[50]

Religion

editBengal was an affluent province with Bengali Muslim as the official religion and constituted a significant minority following a Bengali Hindu majority.[12]

Immigration

editThere was a significant influx of migrants from the Safavid Empire into Bengal during the Mughal period. Persian administrators and military commanders were enlisted by the Mughal government in Bengal.[51] An Armenian community settled in Dhaka and was involved in the city's textile trade, paying a 3.5% tax.[52]

Economy and trade

editThe Bengal Subah had the largest regional economy in that period. It was described as the paradise of nations.[citation needed] The region exported grains, fine cotton muslin and silk, liquors and wines, salt, ornaments, fruits, and metals.[54] European companies set up numerous trading posts in Bengal during the 17th and 18th centuries. Dhaka was the largest city in Bengal and the commercial capital of the empire.[citation needed] Chittagong was the largest seaport, with maritime trade routes connecting it to Arakan, Ayuthya, Aceh, Melaka, Johore, Bantam, Makassar, Ceylon, Bandar Abbas, Mocha and the Maldives.[55]

Parthasarathi estimates that grain wages for weaving and spinning in Bengal and Britain were comparable in the mid 18th century.[56] However, due to the scarcity of data, more research is needed before drawing any conclusions.[57]

Bengal had many traders and bankers. Among them was the Jagat Seth Family, who were the wealthiest bankers in the region.

Agrarian reform

editThe Mughals launched a vast economic development project in the Bengal delta which transformed its demographic makeup.[58] The government cleared vast swathes of forest in the fertile Bhati region to expand farmland. It encouraged settlers, including farmers and jagirdars, to populate the delta. It assigned Sufis as the chieftains of villages. Emperor Akbar re-adapted the modern Bengali calendar to improve harvests and tax collection. The region became the largest grain producer in the subcontinent.

There are sparse accounts of the Bengal revenue administration in Abul Fazl's Ain-i-Akbari and some in Mirza Nathan's Baharistan-i-Ghaibi.[59] According to the former,

The demands of each year are paid by instalments in eight months, they (the ryots) themselves bringing mohurs and rupees to the appointed place for the receipt of revenue, as the division of grain between the government and the husbandman is not here customary. The harvests are always abundant, measurement is not insisted upon, and the revenue demands are determined by estimate of the crop.[59]

In contrast, the Baharistan says there were two collections per year, following the spring and autumn harvests. It also says that, at least in some areas, revenue demands were based on survey and land measurement.[59]

Bengali peasants were quick to adapt to profitable new crops between 1600 and 1650. Bengali peasants rapidly learned techniques of mulberry cultivation and sericulture, establishing Bengal Subah as a major silk-producing region of the world.[60]

The increased agricultural productivity led to lower food prices. In turn, this benefited the Indian textile industry. Compared to Britain, the price of grain was about one-half in South India and one-third in Bengal, in terms of silver coinage. This resulted in lower silver coin prices for Indian textiles, giving them a price advantage in global markets.[61]

Industrial economy

editIn the 17th century, Bengal was an affluent province that was, according to economic historian Indrajit Ray, globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding.[9] Bengal's capital city of Dhaka was the empire's financial capital, with a population exceeding a million people, and with an estimated 80,000 skilled textile weavers. It was an exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpeter, and agricultural and industrial produce.[10] Bengal's mining, metallurgy, and shipping in this era have been described as proto-industrialization.[62]

Many historians have built on the perspective of R. C. Dutt who wrote, "The plunder of Bengal directly contributed to the Industrial Revolution in Britain."[12][13][14][15] This analysis states that the capital amassed from Bengal was used to invest in British industries such as textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution and greatly increase British wealth, while at the same time leading to deindustrialization in Bengal.[12][13][14][10] According to Indrajit Ray, domestic industries expanded for decades even after Plassey. Although colonial-based price manipulation and state discrimination initiated from the 1790s, Bengal's industries retained some comparative advantages. Ray states that "Bengali entrepreneurs continued in industries such as cotton and silk textiles where there were domestic market supports", and major deindustrialisation occurred as late as the 1830s to 1850s.[63]

Textile industry

editBengal was a centre of the worldwide muslin, jute and silk trades. During this era, the most important center of jute and cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[64] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.[8] From Bengal, saltpetre was also shipped to Europe, opium was sold in Indonesia, raw silk was exported to Japan and the Netherlands, and cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia and Japan.[65] The jute trade was also a significant factor.

Shipbuilding industry

editBengal had a large shipbuilding industry. Indrajit Ray estimates shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[66] He also assesses ship repairing as very advanced in Bengal.[66]

An important innovation in shipbuilding was the introduction of a flushed deck design in Bengal rice ships, resulting in hulls that were stronger and less prone to leak than the structurally weak hulls of traditional European ships built with a stepped deck design. The British East India Company later duplicated the flushed deck and hull designs of Bengal rice ships in the 1760s, leading to significant improvements in seaworthiness and navigation for European ships during the Industrial Revolution.[67]

Administrative divisions

editIn the revenue settlement by Todar Mal in 1582, Bengal Subah was divided into 24 sarkars (districts), which included 19 sarkars of Bengal proper and 5 sarkars of Orissa. In 1607, during the reign of Jahangir Orissa became a separate Subah. These 19 sarkars were further divided into 682 parganas.[68] In 1658, subsequent to the revenue settlement by Shah Shuja, 15 new sarkars and 361 new parganas were added. In 1722, Murshid Quli Khan divided the whole Subah into 13 chakalahs, which were further divided into 1660 parganas.[citation needed]

Initially the capital of the Subah was Tanda.[citation needed] On 9 November 1595, the foundations of a new capital were laid at Rajmahal by Man Singh I who renamed it Akbarnagar.[69] In 1610 the capital was shifted from Rajmahal to Dhaka[70] and it was renamed Jahangirnagar. In 1639, Shah Shuja again shifted the capital to Rajmahal. In 1660, Muazzam Khan (Mir Jumla) again shifted the capital to Dhaka. In 1703, Murshid Quli Khan, then diwan (prime minister in charge of finance) of Bengal shifted his office from Dhaka to Maqsudabad and later renamed it Murshidabad.[citation needed]

In 1656, Shah Shuja reorganised the sarkars and added Orissa to the Bengal Subah.[citation needed]

The sarkars (districts) and the parganas/mahallahs (tehsils) of Bengal Subah were:[68]

| Sarkar | Pargana |

|---|---|

| Udamabar/Tanda (modern-day areas include North Birbhum, Rajmahal and Murshidabad) | 52 parganas |

| Jannatabad (Lakhnauti) (Modern day Malda division) | 66 parganas |

| Fatehabad | 31 parganas |

| Mahmudabad (modern-day areas include North Nadia and Jessore) | 88 parganas |

| Khalifatabad | 35 parganas |

| Bakla | 4 parganas |

| Purniyah | 9 parganas |

| Tajpur (East Dinajpur) | 29 parganas |

| Ghoraghat (South Rangpur Division, Bogura) | 84 parganas |

| Pinjarah | 21 parganas |

| Barbakabad (West Dinajpur) | 38 parganas |

| Bazuha | 32 parganas |

| Sonargaon modern day Dhaka Division | 52 parganas |

| Srihatta | 8 mahals |

| Chittagong | 7 parganas |

| Sharifatabad | 26 parganas |

| Sulaimanabad | 31 parganas |

| Satgaon (Modern day Hooghly District and Howrah District) | 53 parganas |

| Mandaran | 16 parganas |

Sarkars of Orissa:

| Sarkar | Mahal |

|---|---|

| Jaleswar | 28 |

| Bhadrak | 7 |

| Kotok (Cuttack) | 21 |

| Kaling Dandpat | 27 |

| Raj Mahendrih | 16 |

Government

editThe state government was headed by a Viceroy (Subedar Nizam) appointed by the Mughal Emperor between 1576 and 1717. The Viceroy exercised tremendous authority, with his own cabinet and four prime ministers (Diwan). The three deputy viceroys for Bengal proper, Bihar and Orissa were known as the Naib Nazims. An extensive landed aristocracy was established by the Mughals in Bengal. The aristocracy was responsible for taxation and revenue collection. Land holders were bestowed with the title of Jagirdar. The Qadi title was reserved for the chief judge. Mansabdars were leaders of the Mughal Army, while faujdars were generals. The Mughals were credited for secular pluralism during the reign of Akbar, who promoted the religious doctrine of Din-i Ilahi. Later rulers promoted more conservative Islam.

In 1717, the Mughal government replaced Viceroy Azim-us-Shan due to conflicts with his influential deputy viceroy and prime minister Murshid Quli Khan.[71] Growing regional autonomy caused the Mughal Court to establish a hereditary principality in Bengal, with Khan being recognised in the official title of Nazim. He founded the Nasiri dynasty. In 1740, following the Battle of Giria, Alivardi Khan staged a coup and founded the short-lived Afsar dynasty. For all practical purposes, the Nazims acted as independent princes. European colonial powers referred to them as Nawabs or Nababs.[72]

List of Subadars & Nawab Nazims

editSubahdars

edit| Personal name[73] | Reign | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Munim Khan Khan-i-Khanan منعم خان، خان خاناں |

25 September 1574 – 23 October 1575 | ||

| Hussain Quli Beg Khan Jahan I حسین قلی بیگ، خان جہاں اول |

15 November 1575 – 19 December 1578 | ||

| Muzaffar Khan Turbati مظفر خان تربتی |

1579–1580 | ||

| Mirza Aziz Koka Azam Khan I میرزا عزیز کوکہ،خان اعظم |

1582–1583 | ||

| Shahbaz Khan Kamboh Lahori Mir Jumla I شھباز خان کمبوہ |

1583–1585 | ||

| Sadiq Khan صادق خان |

1585–1586 | ||

| Wazir Khan Tajik وزیر خان |

1586–1587 | ||

| Sa'id Khan سعید خان |

1587–1594 | ||

| Raja Man Singh I راجہ مان سنگھ |

4 June 1594 – 2 September 1606 | ||

| Qutb-ud-din Khan Koka قطب الدین خان کوکہ |

2 September 1606 – 20 May 1607 | ||

| Jahangir Quli Beg جہانگیر قلی بیگ |

1607–1608 | ||

| Sheikh Ala-ud-din Chisti Islam Khan I اسلام خان چشتی |

June 1608 – 1613 | ||

| Qasim Khan Chishti Muhtashim Khan قاسم خان چشتی |

1613–1617 | ||

| Ibrahim Khan Fateh Jang Ibrahim Khan I ابراہیم خان فتح جنگ |

1617–1622 | ||

| Mahabat Khan محابت خان |

1622–1626 | ||

| Mirza Amanullah Khan Jahan II میرزا أمان اللہ ، خان زماں ثانی |

1626 | ||

| Mukarram Khan Chishti مکرم خان |

1626–1627 | ||

| Fidai Khan I فدای خان |

1627–1628 | ||

| Qasim Khan Juvayni Qasim Manija قاسم خان جوینی، قاسم مانیجہ |

1628–1632 | ||

| Mir Muhammad Baqir Azam Khan II میر محمد باقر، اعظم خان |

1632–1635 | ||

| Mir Abdus Salam Islam Khan II اسلام خان مشھدی |

1635–1639 | ||

| Sultan Shah Shuja شاہ شجاع |

1639–1660 | ||

| Mir Jumla II میر جملہ |

May 1660 – 30 March 1663 | ||

| Mirza Abu Talib Shaista Khan I میرزا ابو طالب، شایستہ خان |

March 1664 – 1676 | ||

| Fidai Khan Koka, Fidai Khan II اعظم خان کوکہ، فدای خان ثانی |

1676–1677 | ||

| Sultan Muhammad Azam Shah Alijah محمد اعظم شاہ عالی جاہ |

1678–1679 | ||

| Mirza Abu Talib Shaista Khan I میرزا ابو طالب، شایستہ خان |

1680–1688 | ||

| Ibrahim Khan ibn Ali Mardan Khan Ibrahim Khan II ابراہیم خان ابن علی مردان خان |

1688–1697 | ||

| Sultan Azim-us-Shan عظیم الشان |

1697–1712 | ||

| Others were appointed but did not show up from 1712 to 1717 and managed by Deputy Subahdar Murshid Quli Khan. | |||

| Murshid Quli Khan مرشد قلی خان |

1717–1727 | ||

Nawab Nazims (independent)

edit| Portrait | Regnal name | Personal name | Birth | Reign | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasiri dynasty | |||||

| Jaafar Khan Bahadur Nasiri | Murshid Quli Khan | 1665 | 1717– 1727 | 30 June 1727 | |

| Ala-ud-Din Haidar Jang | Sarfaraz Khan Bahadur Dakhni | ? | 1727–1727 | 29 April 1740 | |

| Shuja ud-Daula | Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan or Mirza Deccani | Around 1670 (date not available) | July 1727 – 26 August 1739 | 26 August 1739 | |

| Ala-ud-Din Haidar Jang | Sarfaraz Khan Bahadur Dakhni | ? | 13 March 1739 – April 1740 | 29 April 1740 | |

| Afsar dynasty | |||||

| Hashim ud-Daula | Muhammad Alivardi Khan Bahadur | Before 10 May 1671 | 29 April 1740 – 9 April 1756 | 9 April 1756 | |

| Siraj ud-Daulah | Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah | 1733 | April 1756 – 2 June 1757 | 2 July 1757 | |

References

edit- ^ Akhtaruzzaman, Muhammad (2012). "Tandah". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ "Rajmahal – India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Dhaka – national capital, Bangladesh". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas (1986). A Socio-intellectual History of the Isnā 'Asharī Shī'īs in India: 16th to 19th century A.D. Vol. 2. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 45–47.

- ^ Rieck, Andreas (15 January 2016). The Shias of Pakistan: An Assertive and Beleaguered Minority. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-061320-4.

- ^ Steel, Tim (19 December 2014). "The paradise of nations". Op-ed. Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ a b Islam, Sirajul (1992). History of Bangladesh, 1704–1971: Economic history. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-512-337-2.

- ^ a b Om Prakash (2006). "Empire, Mughal". In John J. McCusker (ed.). History of World Trade Since 1450. World History in Context. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 237–240. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed). Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Vaughn, James M. (March 2018). "John Company Armed: The English East India Company, the Anglo-Mughal War and Absolutist Imperialism, c. 1675–1690". Britain and the World. 11 (1): 101–137. doi:10.3366/brw.2017.0283.

- ^ a b c d e f Junie T. Tong (2016). Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets. CRC Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-317-13522-7.

- ^ a b c d e John L. Esposito, ed. (2004). The Islamic World: Past and Present. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-19-516520-3. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Shombit Sengupta (8 February 2010). "Bengal's plunder gifted the British Industrial Revolution". The Financial Express. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ The Bengalis. p. 143.

- ^ Richard M. Eaton (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier:1204-1760. Oxford University Press. p. xxiii. ISBN 0-520-20507-3.

- ^ "Humayun". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Tapan Raychaudhuri (1953). Bengal under Akbar and Jahangir: An Introductory Study in Social History. Calcutta: A. Mukherjee. p. 1. OCLC 5585437.

- ^ Tapan Raychaudhuri (1953). Bengal under Akbar and Jahangir: An Introductory Study in Social History. Calcutta: A. Mukherjee. p. 2. OCLC 5585437.

- ^ Tapan Raychaudhuri (1953). Bengal under Akbar and Jahangir: An Introductory Study in Social History. Calcutta: A. Mukherjee. pp. 17–18. OCLC 5585437.

- ^ "Dhaka". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler (1953). The Cambridge History of India: The Indus civilization. Vol. Supplementary. Cambridge University Publishers. pp. 237–.

- ^ Chakma, Saradindu Shekhar (2006). Ethnic cleansing in Chittagong Hill Tracts. Dhaka: Ankur Prakashani. p. 23. ISBN 978-984-464-164-8.

- ^ Farooqui Salma Ahmed (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1.

- ^ Kunal Chakrabarti; Shubhra Chakrabarti (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. Scarecrow Press. pp. 237–. ISBN 978-0-8108-8024-5.

- ^ "Bengal, nawabs of (act. 1756–1793), rulers in India". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/63552. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "ʿAlī Vardī Khān | nawab of Bengal". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Bengal | region, Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Odisha - History". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Silliman, Jael (28 December 2017). "Murshidabad can teach the rest of India how to restore heritage and market the past". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ A Comprehensive History of India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-207-2506-5.

- ^ William Dalrymple (2019). The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-63557-395-4.

- ^ a b c d "The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760". University of California Press. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Hussein, Aklam. History of Bangladesh, 1704-1971. University of Michigan, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. p. 80. ISBN 9789845123372.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Kirti (2006). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660-1760. Cambridge University Press. p. 253. ISBN 9780521031592.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780521028226.

- ^ Kishore, Gupta (1962). Sirajuddaullah and the East India Company, 1756-1757: Background to the Foundation of British Power in India. Brill Archive. p. 23.

- ^ "Forgotten Indian history: The brutal Maratha invasions of Bengal". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Nitish K. Sengupta (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

- ^ Jaswant Lal Mehta (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India, 1707-1813. New Dawn Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- ^ Jadunath Sarkar (1991) [First published 1932]. Fall Of The Mughal Empire (4th ed.). Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-1149-1.

- ^ Momtazur Rahman Tarafdar (1965). Husain Shahi Bengal, 1494–1538 A.D.: A Socio-Political Study. Asiatic Society of Pakistan. p. 105. OCLC 43324741.

- ^ Tim Steel (31 October 2014). "Gunpowder plots". Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Saltpetre". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 247.

- ^ "Nimtoli Deuri becomes heritage museum". The Daily Star. 17 January 2019. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "- YouTube" ঢাকার নিমতলি দেউড়ি এখন ঐতিহ্য জাদুঘর. Nimtoli Deuri Becomes Heritage Museum. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "In Search of Bangladeshi Islamic Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Janam Mukherjee (2015). Hungry Bengal: War, Famine and the End of Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-020988-9. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Karim, Abdul (2012). "Iranians, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Ali, Ansar; Chaudhury, Sushil; Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Armenians, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2007). Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford University Press. Table A.7. ISBN 978-1-4008-3138-8.

- ^ Nanda, J. N. (2005). Bengal: The Unique State. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Pearson, Michael (2003). The Indian Ocean. Routledge. pp. 136, 164. ISBN 978-0-415-21489-6.

[page 136: From 1500-1850,] in Bengal the main market was Chittagong ... [page 164:] Mir Jumla, who in the 1640s had his own ships ... travelling all over the ocean: to Bengal, Surat, Arakan, Ayuthya, Aceh, Melaka, Johore, Bantam, Makassar, Ceylon, Bandar Abbas, Mocha and the Maldives.

- ^ Prasannan Parthasarathi (2011). Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600-1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Prasannan Parthasarathi (2011). Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. pp. 312–313. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Tapan Raychaudhuri (1953). Bengal under Akbar and Jahangir: An Introductory Study in Social History. Calcutta: A. Mukherjee. p. 24. OCLC 5585437.

- ^ Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. I.5. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ Prasannan Parthasarathi (2011). Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Abhay Kumar Singh (2006). Modern World System and Indian Proto-industrialization: Bengal 1650–1800. Vol. I. Northern Book Centre. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-7211-201-1.

- ^ Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 245–254. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760 Archived 4 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, page 202, University of California Press

- ^ John F. Richards (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ a b Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ "Technological Dynamism in a Stagnant Sector: Safety at Sea during the Early Industrial Revolution" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Jadu-Nath, ed. (1949). Ain I Akbari Of Abul Fazl-i-allami. Vol. II. Translated by Jarrett, H. S. Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. pp. 142–55.

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1984). Sinh, Raghubir (ed.). A History of Jaipur, c. 1503–1938. Orient Longman. pp. 81, 94. ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- ^ Gommans, Jos (2002). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire, 1500–1700. Oxon: Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 0-415-23988-5.

- ^ Chatterjee, Anjali (2012). "Azim-us-Shan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Nawab". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (1993). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 325–6. ISBN 0-520-20507-3.

Further reading

edit- Irfan Habib (1999) [First published 1963]. The Agrarian System of Mughal India, 1556–1707 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-807742-8.