This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

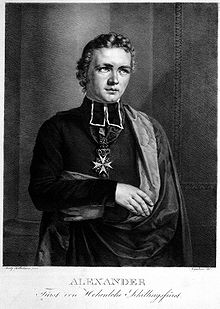

Prince Alexander Leopold Franz Emmerich of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (17 August 1794 – 17 November 1849) was a German priest and reputed miracle-worker.

Early life and education

editAlexander of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst was born at Kupferzell, near Waldenburg. He was a son of Charles Albert II, Prince of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1742-1796) and his second wife, Hungarian Baroness Judith Reviczky de Revišné (from 1753 to 1836), the daughter of a Hungarian nobleman. They entrusted his early education to the church and ex-Jesuit Rid. In 1804, he entered the Theresianum at Vienna, in 1808 the academy at Bern, in 1810 the archiepiscopal seminary at Vienna, and afterwards he studied at Tyrnau and Ellwangen.[1]

Career

editHe was ordained priest in 1815, and in the following year he went to Rome.[2] On his return he made a pilgrimage to Loreto, and again arrived at Munich on 23 March 1817. In June of the same year he was made ecclesiastical councillor, and in 1821, canon of Bamberg.[1]

About this time began the numerous miraculous cures which are alleged to have been effected through the prayers of Hohenlohe. On 1 February 1821, he was suddenly cured at Hassfurt of a severe pain in the throat in consequence of the prayers of a devout peasant named Martin Michel. His belief in the efficacy of prayer was greatly strengthened by this cure, and on 21 June 1821, he succeeded in curing the Princess Mathilda von Schwarzenberg, who had been a paralytic for eight years, by his prayers which he joined with those of Martin Michel.[1]

Having asked the pope whether he was permitted to attempt similar cures in the future, he was told not to attempt any more public cures, but he continued them in private. He would specify a time during which he would pray for those that applied to him, and in this manner he effected numerous cures not only on the Continent, but also in England, Ireland, and the United States. He acquired such fame as a performer of miraculous cures that a cult began to develop around him. Crowds from several countries flocked to partake of the beneficial influence of his supposed supernatural gifts.[2]

Ann Mattingly's cure

editAnn Mattingly, the widowed sister of Thomas Carbery, mayor of Washington D.C., became seriously ill in 1817, and was eventually diagnosed with cancer. As the illness progressed, some friends suggested they contact Hohenlohe. Laudanum proved ineffective and her doctors advised palliative care. Stephen Dubuisson, of St. Patrick's Catholic Church wrote to Hohenlohe. In his response, Hohenlohe recommended a novena, and advised that he offered Mass and prayers on the 10th of each month at 9 a.m. for those outside Europe who wished to join with him in prayer. Dubuisson calculated what time it would be in Washington when it was 9 o'clock in Hamburg, and conducted his Mass accordingly.[3] It was reported to William Matthews, pastor of St. Patrick's, that Mattingly was instantly restored to health and that even large bedsores on her back had disappeared. Matthews immediately went to visit her; according to him, she was smiling and greeted him at the door. Mattingly's quick recovery was noted by several prominent Washington physicians, and by those attending to her, as shocking.[4] When word of the event circulated, it was sensationalized by the local press. Matthews responded by criticizing the priests who exaggerated the story, but described the event to the National Intelligencer as a miracle.[4]

Mattingly's astonishing healing became a polarizing event, heralding a rise in anti-Catholicism in the United States.[5]

Ultimately, on account of the interference of the authorities with his operations, he went to Vienna in 1821 and then to Hungary, where he became a canon of Grosswardein. In 1844 he was made titular Bishop of Sardica. In 1849, he died at Vöslau near Vienna.[2]

Alexander was the author of a number of ascetic and controversial writings, which were collected and published in one edition by S. Brunner in 1851.[2]

Ancestry

edit| Ancestors of Prince Alexander of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Ott, Michael. "Alexander Leopold Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 12 October 2022 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hohenlohe". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 573.

- ^ Clark, Allen C. "The Mayors of the Corporation of Washington: Thomas Carbery", Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., vol. 19, 1916, pp. 79–81. JSTOR This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Durkin, Joseph Thomas. William Matthews: Priest and Citizen. New York: Benziger Brothers. (1963) pp. 132–137

- ^ Schultz, Nancy Lusignan. Mrs. Mattingly's miracle : the prince, the widow, and the cure that shocked Washington City, New Haven : Yale University Press, 2011, ISBN 9781283096249

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.