La Crosse (/ləˈkrɒs/ lə-KROSS)[6] is a city in and the county seat of La Crosse County, Wisconsin, United States. Positioned alongside the Mississippi River, La Crosse is the largest city on Wisconsin's western border.[7] La Crosse's population was 52,680 as of the 2020 census.[2] The city forms the core of the La Crosse–Onalaska metropolitan area, which includes all of La Crosse County and Houston County, Minnesota, with a population of 139,627.[8]

La Crosse, Wisconsin | |

|---|---|

| |

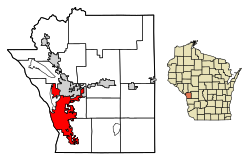

Location of La Crosse in La Crosse County, Wisconsin. | |

| Coordinates: 43°48′48″N 91°13′59″W / 43.81333°N 91.23306°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Wisconsin |

| County | La Crosse |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council government |

| • Mayor | Mitch Reynolds (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 23.79 sq mi (61.61 km2) |

| • Land | 21.70 sq mi (56.21 km2) |

| • Water | 2.08 sq mi (5.40 km2) |

| Elevation | 669 ft (204 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 52,680 |

| • Estimate (2022)[3] | 51,380 |

| • Rank | US: 763th WI: 12th |

| • Density | 2,214.38/sq mi (911.34/km2) |

| • Urban | 98,872 (US: 314th) |

| • Metro | 139,211 (US: 299th) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (Central) |

| Zip Code | 54601, 54602, 54603 |

| Area code | 608 |

| FIPS code | 55-40775[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1567672[5] |

| Waterways | Mississippi River, Black River, La Crosse River |

| Public Transit | La Crosse MTU SMRT Amtrak |

| Website | www |

La Crosse's economy serves as a regional educational, medical, manufacturing, and transportation hub for Western Wisconsin producing a gross domestic product (GDP) of $9.7 billion as of 2022.[9] The city is a college town with nearly 20,000 students and is home to the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse, Viterbo University, and Western Technical College. Furthermore, the La Crosse area is home to the headquarters or regional offices of Kwik Trip, Organic Valley, Mayo Clinic, Gundersen Health System, Gensler, La Crosse Technology, City Brewing Company, and Trane. La Crosse County is a top ten tourist destination in the state with $433 million in travel-related spending generated in 2023.[10]

History

edit18th century

editThe first Europeans to see the region were French fur traders who traveled the Mississippi River in the late 17th century. There is no written record of any visit to the site until 1805, when Lt. Zebulon Pike mounted an expedition up the Mississippi River for the United States. Pike recorded the location's name as "Prairie La Crosse". The name originated from the game with sticks that resembled a bishop's crozier or la crosse in French, which was played by Native Americans there.[11][12]

19th century

editIn 1841, the first white settlement at La Crosse was established when Nathan Myrick, a New York native, moved to the village at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin to work in the fur trade. Myrick was disappointed to find that because many fur traders were already well-entrenched there, there were no openings for him in the trade. As a result, he decided to establish a trading post upriver at the then still unsettled site of Prairie La Crosse. In 1841, he built a temporary trading post on Barron Island (now called Pettibone Park), which lies just west of La Crosse's present downtown. The following year, Myrick relocated the post to the mainland prairie, partnering with H. J. B. Miller to run the outfit.[13]

The spot Myrick chose to build his trading post proved ideal for settlement. It was near the junction of the Black, La Crosse, and Mississippi Rivers. In addition, the post was built at one of the few points along the Wisconsin side of the Mississippi River where a broad plain, ideal for development, existed between the river's bank and the tall bluffs that line the river valley. Because of these advantages, a small village grew around Myrick's trading post in the 1840s.

In 1844, a small Mormon community settled at La Crosse, building several dozen cabins a few miles (kilometers) south of Myrick's post. Although these settlers relocated away from the Midwest after just a year, the land they occupied near La Crosse continues to bear the name Mormon Coulee.[14] On June 23, 1850, Father James Lloyd Breck of the Episcopal Church said the first Christian liturgy on top of Grandad Bluff.[15] Today, a monument to that event stands atop the bluff, near the parking lot at a scenic overlook.

More permanent development took place closer to Myrick's trading post, where stores, a hotel, and a post office were constructed during the 1840s. Under the direction of Timothy Burns, lieutenant governor of Wisconsin, surveyor William Hood platted the village in 1851. This opened it up for further settlement, which was achieved rapidly as a result of promotion of the city in eastern newspapers. By 1855, La Crosse had grown in population to nearly 2,000 residents, leading to its incorporation in 1856. The city grew even more rapidly after 1858 with the completion of the La Crosse & Milwaukee Railroad, the second railroad connecting Milwaukee to the Mississippi River.

During the second half of the 19th century, La Crosse grew to become one of the largest cities in Wisconsin.[16] It was a center of the lumber industry, for logs cut in the interior of the state could be rafted down the Black River toward sawmills built in the city. La Crosse also became a center for the brewing industry and other manufacturers that saw advantages in the city's location adjacent to major transportation arteries, such as the Mississippi River and the railroad between Milwaukee and St. Paul, Minnesota.

20th century

editAround the turn of the 20th century, the city became a center for education, with three colleges and universities established in the city between 1890 and 1912. Similar to cities across the country, La Crosse saw population stagnation in the latter half of the 20th century as a result of suburbanization. Since 1966, La Crosse has seen its population grow by 10.73%, while its area, miles of sewer, and miles of water mains each grew by more than 50%.[17][18] La Crosse remains the largest city on Wisconsin's western border, and the educational institutions in the city have recently led it toward becoming a regional technology and medical hub.

21st century

editIn 2016, Mayor Tim Kabat and former Mayor John Medinger issued a proclamation apologizing for La Crosse's history as a sundown town that discriminated against African Americans.[19]

Geography

editLa Crosse is located on the western border of the midsection of Wisconsin, on a broad alluvial plain along the east side of the Mississippi River. The Black River empties into the Mississippi north of the city, and the La Crosse River flows into the Mississippi just north of the downtown area. Just upriver from its mouth, this river broadens into a marshland that splits the city into two distinct sections, north and south.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 23.79 square miles (61.62 km2), of which, 21.7 square miles (56.20 km2) is land and 2.08 square miles (5.39 km2) is water.[20]

Surrounding the relatively flat prairie valley where La Crosse lies are towering 500-foot (150 m) bluffs, one of the most prominent of which is Grandad Bluff (mentioned in Life on the Mississippi by Mark Twain), which has an overlook of the three states region. This feature typifies the topography of the Driftless Area in which La Crosse sits. This rugged region is composed of high ridges dissected by narrow valleys called coulees, a French term. As a result, the area around La Crosse is frequently referred to as the "Coulee Region".[21]

Climate

editLa Crosse's location in the United States' Upper Midwest gives the area a temperate, continental climate.[22] The warmest month of the year is July, when the average high temperature is 85.4 °F (29.7 °C), with overnight low temperatures averaging 64.5 °F (18.1 °C). January is the coldest month, with high temperatures averaging 27.4 °F (−2.6 °C), with the overnight low temperatures around 10.5 °F (−11.9 °C).[23]

| Climate data for La Crosse Regional Airport, Wisconsin (1991–2020 normals,[24] extremes 1872–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 57 (14) |

65 (18) |

84 (29) |

93 (34) |

107 (42) |

102 (39) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

93 (34) |

80 (27) |

69 (21) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 45.8 (7.7) |

50.5 (10.3) |

67.7 (19.8) |

81.7 (27.6) |

89.1 (31.7) |

94.0 (34.4) |

95.2 (35.1) |

93.3 (34.1) |

89.9 (32.2) |

81.5 (27.5) |

64.3 (17.9) |

49.5 (9.7) |

97.3 (36.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 27.4 (−2.6) |

32.5 (0.3) |

45.6 (7.6) |

59.6 (15.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

81.7 (27.6) |

85.4 (29.7) |

83.2 (28.4) |

75.5 (24.2) |

61.6 (16.4) |

45.8 (7.7) |

32.6 (0.3) |

58.6 (14.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 18.9 (−7.3) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

35.8 (2.1) |

49.0 (9.4) |

61.0 (16.1) |

71.0 (21.7) |

75.0 (23.9) |

72.8 (22.7) |

64.8 (18.2) |

51.7 (10.9) |

37.6 (3.1) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

48.8 (9.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 10.5 (−11.9) |

14.2 (−9.9) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

38.4 (3.6) |

50.1 (10.1) |

60.4 (15.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

62.3 (16.8) |

54.1 (12.3) |

41.9 (5.5) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

39.1 (3.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −13.8 (−25.4) |

−8.8 (−22.7) |

2.1 (−16.6) |

22.7 (−5.2) |

34.5 (1.4) |

45.7 (7.6) |

52.9 (11.6) |

50.3 (10.2) |

38.1 (3.4) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

12.3 (−10.9) |

−5.9 (−21.1) |

−17.3 (−27.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −43 (−42) |

−36 (−38) |

−28 (−33) |

7 (−14) |

26 (−3) |

33 (1) |

44 (7) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

6 (−14) |

−21 (−29) |

−37 (−38) |

−43 (−42) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.25 (32) |

1.19 (30) |

2.04 (52) |

3.75 (95) |

4.33 (110) |

5.08 (129) |

4.23 (107) |

3.90 (99) |

3.63 (92) |

2.49 (63) |

1.85 (47) |

1.49 (38) |

35.23 (895) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 11.8 (30) |

9.7 (25) |

7.3 (19) |

2.9 (7.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

3.4 (8.6) |

10.9 (28) |

46.3 (118) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.2 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 12.2 | 13.3 | 11.8 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 122.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.6 | 7.2 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 7.5 | 33.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.8 | 72.2 | 70.6 | 64.2 | 65.0 | 69.5 | 72.1 | 75.2 | 77.2 | 71.3 | 75.4 | 77.3 | 71.9 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 7.5 (−13.6) |

12.0 (−11.1) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

34.0 (1.1) |

45.9 (7.7) |

56.7 (13.7) |

62.6 (17.0) |

61.0 (16.1) |

53.1 (11.7) |

39.9 (4.4) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

14.7 (−9.6) |

36.6 (2.5) |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1961–1990)[25][26][27] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods and districts

editLa Crosse has 13 voting districts (wards).[28] Neighborhoods within the city include:

- Bluffside

- Washburn

- Historic Cass & King

- Powell-Poage-Hamilton[29]

- Historic downtown

- Northside (Upper and Lower) and Old Towne North

- Grandview Emerson

- Weigent Hogan

- Hintgen

- College Park (UW–La Crosse campus district)

- Springbrook Clayton Johnson

Area

edit| Land Area | Water Area | Total Area | Population density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970[30] | n/a | n/a | 16.84 | 2,986.10 |

| 1980[30] | n/a | n/a | 18.02 | 2,682.96 |

| 2000[31] | 20.136 | 2.024 | 22.16 | 2,338.36 |

| 2010[31] | 20.516 | 2.021 | 22.537 | 2,277.14 |

| 2015[31] | 20.562 | 2.042 | 22.604 | n/a |

| 2020[31] | 21.703 | 2.085 | 23.788 | 2,214.56 |

| 2021[31] | 21.703 | 2.085 | 23.788 | n/a |

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 3,860 | — | |

| 1870 | 7,785 | 101.7% | |

| 1880 | 14,505 | 86.3% | |

| 1890 | 25,000 | 72.4% | |

| 1900 | 28,895 | 15.6% | |

| 1910 | 30,417 | 5.3% | |

| 1920 | 30,421 | 0.0% | |

| 1930 | 39,614 | 30.2% | |

| 1940 | 42,707 | 7.8% | |

| 1950 | 47,535 | 11.3% | |

| 1960 | 47,258 | −0.6% | |

| 1970 | 50,286 | 6.4% | |

| 1980 | 48,347 | −3.9% | |

| 1990 | 51,140 | 5.8% | |

| 2000 | 51,818 | 1.3% | |

| 2010 | 51,320 | −1.0% | |

| 2020 | 52,680 | 2.7% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 51,380 | [3] | −2.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[32] 2020 Census[2] | |||

2020 census

editAs of the census of 2020,[33] the population was 52,680. The population density was 2,427.3 inhabitants per square mile (937.2/km2). There were 24,221 housing units at an average density of 1,116.0 per square mile (430.9/km2). The population living in college or university student housing was 3,897. The racial makeup of the city was 85.6% White, 4.9% Asian, 2.9% Black or African American, 0.5% Native American, 1.2% from other races, and 4.9% from two or more races. Ethnically, the population was 3.2% Hispanic or Latino of any race.

According to the American Community Survey estimates for 2016–2020, the median income for a household in the city was $46,438, and the median income for a family was $66,928. Male full-time workers had a median income of $43,438 versus $37,215 for female workers. The per capita income for the city was $27,398. About 7.9% of families and 22.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.6% of those under age 18 and 10.9% of those age 65 or over.[34] Of the population age 25 and over, 93.9% were high school graduates or higher and 36.5% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[35]

Religion

editThe city has a variety of religious traditions and communities, including Catholicism, Protestantism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodox, Judaism, Unitarian Universalism, and Islam.

La Crosse is the episcopal see for the Roman Catholic Diocese of La Crosse. The Cathedral of Saint Joseph the Workman serves as the seat of the Diocese. The city is also home to St. Rose of Viterbo Convent, the mother house of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, and the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe. An independent catholic school district in the city, La Crosse Aquinas Catholic Schools, is also overseen by the diocese.

Protestant churches in the city include Lutheran, Evangelical, Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and independent traditions. The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod has five churches in La Crosse: First Lutheran Church,[36] Grace Lutheran Church,[37] Immanuel Lutheran Church,[38] Mt. Calvary Lutheran Church,[39] and St. John's Lutheran Church.[40] La Crosse is also home to two churches affiliated with the Evangelical Free Church of America; Bethany Church,[41] and Neighborhood City Church.[42] Christ Church of La Crosse, the city's Episcopal church, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. St. Elias Antiochian Orthodox Church, the city's Eastern Orthodox Church, is listed on the city's local register of Historic places.

Other religious groups within the city include: the Congregation Sons of Abraham, a Jewish synagogue; the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of La Crosse, which has held services since 1951;[43] the Islamic Society Othman Bin Afaan; and the Hmong Faith Alliance Church.

Economy

editLa Crosse is the home and current global headquarters of several corporations and organizations, including:

- Allergy Associates of La Crosse and Allergychoices, Inc., national allergy clinic and allergy services organization

- Altra Federal Credit Union, regional credit union[44]

- City Brewing Company, former Heileman Old Style brewery[45]

- Franciscan Skemp Medical Center, health care network with flagship campus in La Crosse

- Gundersen Health System, health care network with flagship campus in La Crosse[46]

- Kwik Trip, regional gas and convenience stores[47]

- La Crosse Technology, manufacturer of atomic clocks and weather stations

- Marine Credit Union, regional credit union

Corporations founded and formerly headquartered in La Crosse include:

- Cargill, America's now largest privately held corporation founded in La Crosse[48]

- La Croix Sparkling Water, carbonated drink originally created by the G. Heileman Brewing Company

- LaCrosse Footwear, footwear company founded in 1897[49]

- Trane, international air conditioning, acquired by Ingersoll-Rand in 2008[50]

Largest employers

editAs of 2012[update], the 10 largest employers in La Crosse were:[51]

- Gundersen Health System

- Mayo Clinic Health System (Franciscan Skemp Medical Center)

- Trane

- Kwik Trip

- La Crosse County

- School District of La Crosse

- University of Wisconsin–La Crosse

- Logistics Health Incorporated

- City of La Crosse

- Western Technical College

Shopping

editLa Crosse and the surrounding communities form a regional commercial center and shopping hub. In the northeastern region of the city lies the area's largest shopping center, Valley View Mall. The surrounding area includes numerous big-box stores, and many restaurants. Other shopping centers in the La Crosse region include Three Rivers Plaza, Marsh View Center, Shelby Mall, Jackson Plaza, Bridgeview Plaza, and the Village Shopping Center. Downtown La Crosse has experienced a resurgence in recent years, providing shopping, farmers' markets, hotels, restaurants, and specialty shops.

Arts and culture

editLa Crosse has over 30 active arts organizations.[52] The Pump House Regional Arts Center hosts visual arts exhibits throughout the year plus its own series of jazz, folk, and blues performers. The La Crosse Symphony is the city's regional orchestra and the La Crosse Community Theater has won both regional and national acclaim.[citation needed] The city is home to the Blue Stars Drum and Bugle Corps, a member of Drum Corps International. Other arts sites include Viterbo University Fine Arts building, UW–La Crosse Art Gallery and Theater, and the La Crosse Center, which hosts national performers.[53][54] Local sculptor Elmer Petersen has created sculptures that are exhibited throughout the downtown area, including La Crosse Players and the Eagle in Riverside Park.[55] It also hosts a yearly St Patrick's Day Parade as well as Irishfest La Crosse in August[56]

The La Crosse Center, a convention center and arena located in downtown La Crosse on the Mississippi River, hosts a variety of sporting events, concerts, exhibits, and shows. The city annually hosts Oktoberfest USA, an Oktoberfest celebration first established in 1961.[57]

Parks and recreation

editSport

editThe La Crosse Loggers[58] (baseball) and La Crosse Steam[59] (softball) of the Northwoods League play at their home field at Copeland Park on the north side of La Crosse in the summer months. In 2017, the La Crosse Showtime began play in the American Basketball Association at La Crosse Center. In the past, the La Crosse Center has been home to the Catbirds and the Bobcats of the CBA, as well as the River Rats of the IFL, the Spartans of the IFL and the Night Train of the NIFL. In the winter season, the Coulee Region Chill was a junior team in the North American 3 Hockey League at the Green Island Ice Arena.[60] Additionally, the area's only ski hill, Mt. La Crosse, opened in 1959 and has 19 slopes and trails. The ski hill is home to Damnation!, Mid-America's steepest trail.[61]

The University of Wisconsin–La Crosse's Eagles compete in NCAA Division III. The university's 10,000 seat Veterans Memorial Field for football (turf field) and outdoor timed track opened in 2009 and hosts the WIAA Wisconsin high school outdoor track and field state championships.[62]

The La Crosse Fairgrounds Speedway, located in nearby West Salem, is the first and only paved NASCAR-sanctioned asphalt stock car racing track in Wisconsin.[63]

Parks

editRiverside Park is situated on the riverfront of downtown La Crosse near the Blue Bridges. It hosts events such as Riverfest, Fourth of July fireworks, Oktoberfest, and the Rotary Lights. Several steamboats make stops along the river in the park, including the American Queen, La Crosse Queen, and Julia Belle Swain. The park has walking/running trails.[64] The park was previously home to a controversial Statue of Hiawatha. Long standing public debate about whether the statue was offensive or presented a caricature based on stereotypes of Native Americans eventually led to its removal in 2020, nearly 60 years after it was erected.[65][66]

Pettibone Park is located on Baron Island, across the river from Riverside Park and the downtown area. The island was originally part of the state of Minnesota. The land was transferred to Wisconsin and eventually the City of La Crosse following a border dispute that was resolved in 1919.[67] Today the park has a variety of recreational facilities, including a beach and disc golf course.

An extensive marsh, a natural floodplain created by the La Crosse River, divides the city between north and south. The area is protected as an important wildlife habitat and watershed to the Mississippi River. Several biking and walking paths cross through the marshland which is also used for canoeing, fishing and trapping.[68] On the southern end of the marsh lies Myrick Park. The park was named after the city's first European settler: Nathan Myrick. It has many recreational amenities as well as a nature center and environmental education department.[69] Hunting and fishing are very popular all seasons of the year and the Mississippi and other rivers, sloughs, creeks, lakes, the Upper Mississippi River Wildlife Refuge and hilltops and valleys with public woodlands are available to sportsmen and families.

Government

editThe city government employs a weak mayor form of the mayor-council system. The mayor is elected at-large, while the 13 members of the Common Council are elected per aldermanic districts.[70] Mitch Reynolds defeated Vicki Markussen in the 2021 La Crosse Mayoral election, succeeding retiring incumbent Tim Kabat. Kabat served as Mayor from 2013 to 2021.[71]

Both the city and county of La Crosse have voted Democratic in every presidential election since 1988.[72] In the 2016 Presidential Election, Hillary Clinton won by 52% of the City of La Crosse. In the 2012 presidential election, Barack Obama won 65% of the city of La Crosse[73] and 58% of La Crosse County.[74] In 2014, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel ranked La Crosse as one of Wisconsin's top performing Democratic cities.[75]

In the United States Congress, Republican Derrick Van Orden has represented La Crosse as part of Wisconsin's 3rd congressional district since 2023. The city is almost coterminous with the 95th Wisconsin State Assembly District and is represented by Democrat Jill Billings. Additionally, Democrat Steve Doyle currently represents suburban La Crosse County in the 94th Assembly District. La Crosse is part of the State Senate District 32 and is represented by Democrat Brad Pfaff.

Mayors

editSource:[76]

- Thomas Benton Stoddard (1856)

- Erasmus D. Campbell (1857)

- David Taylor (1858)

- James I. Lyndes (D) (1859)

- John M. Levy (1860)

- Wilson Colwell (1861)

- Albert W. Pettibone (1862–1864)

- William J. Lloyd (1865)

- John M. Levy (1866–1867)

- Theodore Rodolf (1868)

- Charles. L. Colman (1869)

- Theodore Rodolf (1870)

- Alexander McMillan (1871)

- James I. Lyndes (1872)

- Gysbert Van Steenwyk, Sr. (1873)[77]

- Gilbert M. Woodward (1874)[77]

- James J. Hogan (1875–1876)

- George Edwards (1877)

- David Law (1878–1879)

- Joseph Clark (1880)

- Hiram F. Smiley (1881)

- David Law (1882–1883)

- W. A. Roosevelt (1884)

- D. Frank Powell (1885–1886)

- David Austin (1887–1889)

- John Dengler (1889–1891)

- F. A. Copeland (1891–1893)[77]

- D. Frank Powell (1893–1897)

- James McCord (1897–1899)

- W. A. Anderson (1899–1901)

- Joseph Boschert (1901–1903)

- William Torrance (1903–1907)

- Ori J. Sorenson (1909–1911)[78]

- W. A. Anderson (1907–1909)

- Ori J. Sorenson (1909–1911)

- John Denger (1911–1913)

- Ori J. Sorenson (1913–1915)

- Arthur A. Bentley (1915–1923)[79]

- Joseph J. Verchota (1923–1929)

- John E. Langdon (1929–1931)

- Joseph J. Verchota (1931–1935)

- C. August Boerner (1935–1939)

- Joseph J. Verchota (1939–1947)

- Charles A. Beranek (1947–1949)

- Henry J. Ahrens (1949–1955)[77]

- Milo Knutson (1955–1965)[80]

- Warren Loveland (1965–1971)[81]

- W. Peter Gilbertson (1971–1975)

- Patrick Zielke (April 20, 1975 – April 15, 1997)[82]

- John Medinger (April 15, 1997 – April 19, 2005)

- Mark Johnsrud (April 19, 2005 – April 21, 2009)

- Mathias Harter (R) (April 21, 2009 – April 16, 2013)

- Tim Kabat (D) (April 16, 2013 – April 20, 2021)[83]

- Mitch Reynolds (D) (April 20, 2021–present)[84]

Education

editLa Crosse campus

The La Crosse area is served by the School District of La Crosse, which as of 2022, has a total enrollment of 6,139 students.[85] As of 2021, the district has 16 separate facilities, providing a total of 20 elementary, middle, high, and charter school programs.[86] In 2021, the school district proposed to consolidate the district's largest high schools, Central High School and Logan High School, into a new facility. This plan was voted down in a district-wide referendum in November 2022.[87]

Catholic private schools in La Crosse include La Crosse Aquinas Catholic Schools, a Roman Catholic school district affiliated with the Diocese of La Crosse, which includes Aquinas High School and Aquinas Middle School.[88] Another Roman Catholic school, the Providence Academy, is independent from the district and has no affiliation with the Diocese.[89]

Lutheran private schools in La Crosse include First Lutheran School, Immanuel Lutheran School, and Mt. Calvary-Grace Lutheran School, which are part of the La Crosse Area Lutheran Schools organization and affiliated with the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. The region's largest Lutheran high school, Luther High School is located in Onalaska, Wisconsin.[90]

La Crosse is the home of three regional colleges and universities. The University of Wisconsin–La Crosse is the region's leading public university. Western Technical College is a public community college located in the city. La Crosse is also home to Viterbo University, a Roman Catholic private institution.[91] The Health Science Center exists as a combined effort of all the La Crosse medical centers, universities, and government agencies with a goal of advancing students in the medical fields.[citation needed]

Media

editLa Crosse's largest newspaper is the daily La Crosse Tribune which serves the Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa regions. The Racquet is the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse's free weekly paper. Free weekly tabloids include the Foxxy Shopper and the Buyer's Express. Regional magazines, including the Coulee Parenting Connection and the Coulee Region Women, are also produced in the city.

Television

edit| Channel | Callsign | Affiliation | Branding | Subchannels | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Virtual) | Channel | Programming | |||

| 8.1 | WKBT KQEG-CD |

CBS | WKBT 8 | 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 |

MyNetworkTV ION Dabl QVC HSN |

| 14.1 | W34FC-D | CW | La Crosse/Eau Claire CW | 14.2 14.3 14.4 13.10 |

Heroes & Icons Start TV MeTV NBC (WEAU) |

| 19.1 | WXOW | ABC | WXOW 19 | 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 |

Decades This TV Court TV Justice Network |

| 25.1 | WLAX | FOX | FOX 25/48 | 25.2 25.3 25.4 |

Antenna TV Laff Grit |

| 26.1 | WZEO-LD | Buzzr | |||

| 31.1 | WHLA | PBS | PBS Wisconsin | 31.2 31.3 31.4 |

Wisconsin Channel Create PBS Kids |

AM radio

edit| AM radio stations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Call sign | Name | Format | |

| 580 AM | WKTY | Sports | ||

| 1410 AM | WIZM | News talk 1410 | News/Talk | |

| 1490 AM | WLCX | Eagle 1490 | News/Talk | |

| 1560 AM | WKBH | Relevant Radio | Catholic | |

FM radio

edit| FM radio stations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Call sign | Name | Format |

| 88.1 FM | K201BW (KZSE Translator) |

MPR News | Public |

| 88.9 FM | WLSU | Wisconsin Public Radio | Classic |

| 90.3 FM | WHLA | Wisconsin Public Radio | Public |

| 91.1 FM | KXLC | Minnesota Public Radio | Public |

| 91.9 FM | K220EP (KFSI Translator) |

KFSI 92.9 | Christian |

| 91.9 FM | WDRT | Driftless Community Radio | Community |

| 92.3 FM | K222AG (WIZM-AM Translator) |

News talk 1410 | News/Talk |

| 93.3 FM | WIZM | Z93.3 | Top 40/CHR |

| 93.7 FM | K229BH (WWIB Translator) |

103.7 WWIB | Christian |

| 94.1 FM | W231DL (WKBH-AM Translator) |

Relevant Radio | Catholic |

| 94.5 FM | WTMB | Classic Rock 94.5 | Classic rock |

| 94.7 FM | KCLH | Classic Hits 94.7 | Classic Hits |

| 95.7 FM | WRQT | 95.7 The Rock | Active Rock |

| 96.1 FM | WLXR | Mix 96.1 | Hot AC |

| 96.7 FM | K244FM (WKTY-AM Translator) |

Sports | |

| 97.1 FM | WCOW | Cow 97.1 Country | Country |

| 97.9 FM | K250AZ | Magic 97.9 | Adult Contemporary |

| 98.9 FM | WVCX | VCY America | Christian |

| 99.3 FM | KWMN | Winona Sports Network | Sports |

| 99.7 FM | WWIS | The Star | Classic Country |

| 100.1 FM | WLCW | K-Love | Christian Contemporary |

| 100.5 FM | KDHK | Hawk Rawk | Rock |

| 101.1 FM | KRIV | 101.1 The River | Classic Hits |

| 101.9 FM | K270AG (WFBZ Translator) |

105.5 ESPN | Sports |

| 102.7 FM | WKBH-FM | 102.7 WKBH | Classic Rock; Classic Hits |

| 103.5 FM | KNEI | Bluff Country | Country |

| 104.5 FM | WAXX | Today's WAXX 104.5 | Country |

| 104.9 FM | WEQL | Prayz Network | Christian Contemporary |

| 105.5 FM | WFBZ | 105.5 ESPN | Sports |

| 105.9 FM | WKPO | KPO-FM | Adult Hits |

| 106.3 FM | WQCC | Kicks 106.3 | Country |

| 106.7 FM | W294CU (WIZM-AM Translator) |

News talk 1410 | News/Talk |

| 107.1 FM | W296EH (WKBH-FM Translator) |

Alt 107.1 | Alternative rock |

| 107.7 FM | W299AC (KQYB Translator) |

KQ98 | Country |

Transport

editAirport

editThe La Crosse Regional Airport, (KLSE) located on French Island, provides direct scheduled passenger service to Chicago through American Airlines regional carrier Air Wisconsin. Sun Country and Xtra Airways provide charter service to Laughlin, Elko, Nevada, and other destinations. The airport also serves general aviation for the La Crosse region.[92]

Roads

editThe city is served by several major highways and Interstate, including Interstate 90, U.S. Highway 14, U.S. Highway 53, U.S. Highway 61, Wisconsin State Highway 35, Wisconsin State Highway 16, and Wisconsin State Highway 33.[citation needed]

The Mississippi River Bridge, also known as the Cass St. bridge and the newer Cameron Street bridge (photo with blue arch) both connect downtown La Crosse with La Crescent, Minnesota. These two bridges cross the Mississippi River, as does the Interstate 90 bridge located just northwest of La Crosse, connecting Wisconsin and Minnesota.[citation needed]

Walking and Cycling

editIn 2012, the City of La Crosse was the first city in Wisconsin to pass a Green Complete Streets ordinance. This ordinance requires that when roads are reconstructed the needs of stormwater management and the safety of bicycles and pedestrians are taken into account in the new design. The same year, the city passed the Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan to guide improvements to the transportation network for those walking or cycling in the city.[93]

By 2018, La Crosse had 7.7 miles (12.4 km) of on-street bike lanes, 17.1 miles (27.5 km) of paved bike paths, and 12 miles (19 km) of unpaved paths.[94] As of 2021, however, La Crosse had no protected bike lanes, while bike infrastructure has generally gone unmaintained[clarification needed] through the winter months.[citation needed]

A new bikeshare system debuted in downtown La Crosse in April 2021 through a partnership of La Crosse Neighborhoods, Inc and Koloni, an Iowa based bikeshare company. It is hoped that this service will be expanded across the city in the near future. The system has grown each year from 8 bikeshare stations and 40 bikes available for use in 2021, to 10 stations and 50 bikes in 2022 and to 15 stations and 75 bikes in 2023.[95][96]

The interstate Mississippi River Trail passes through La Crosse. However, the trail does not follow a dedicated multi-use path. The La Crosse River Trail and the Great River State Trail pass through the northern edge of the city. These trails combine to form one continuous trail from Trempealeau to Reedsburg. They are rail trails built on the former roadbed of the Chicago and Northwestern Railway.[citation needed]

Public Transit

editMain Articles: La Crosse Municipal Transit Utility, Scenic Mississippi Regional Transit

Public transit in La Crosse began with the opening of a horse-drawn streetcar line in 1878. Over time, more streetcar lines were added, and by 1893, all streetcars had been electrified. Beginning in the early 20th century, however, increasing car ownership led to a decline of the privately run streetcar system. As a result, buses began to replace streetcars throughout the city. By November 1945, the last streetcar line closed. The City of La Crosse took over operations of the buses in the 1970s from the Mississippi Valley Public Service Company, as the buses could no longer be operated profitably.[citation needed]

In 1945, in the first timetable after streetcar service had ended, there were four bus routes. The earliest bus left at 5:40 am and the last bus returned at 1:00 am. Buses ran at a 10 to 15-minute headway throughout the day. In total, the buses provided 1519.95 hours of service per week. Today, in 2021, the MTU provides only 1141.6 hours of service per week, a decline of 24.89%.[citation needed]

The City of La Crosse's MTU bus service with routes reaching out to the suburbs served over one million users in 2007.[97] As of 2021, the MTU operates 11 routes with the earliest buses beginning their routes at 5:12 am and running until 10:40 pm at the latest.[98]

In addition to the MTU, a regional bus service, Scenic Mississippi Regional Transit, provides service to Prairie du Chien, Viroqua, Tomah, and points in-between. The service has four routes, which only run on weekdays.[99]

Waterways

editOn the Mississippi River, cargo is transported to and from this area to St Paul and St Louis, using towboats, primarily moving dry bulk cargo barges for coal, grain, and other low-value bulk goods.[citation needed]

Lock and Dam No. 7 on the Mississippi River is located approximately 4.5 miles (7.2 km) upstream from Downtown La Crosse.[citation needed]

Rail transport

editThe first rail line to reach La Crosse arrived in 1858 from Milwaukee constructed by the Milwaukee & La Crosse Railroad. This later became the main line of the Milwaukee Road. After the Milwaukee Road went bankrupt it became part of the Soo Line Railroad in 1985 and later came under the control of Canadian Pacific Railway. This line provides the track on which the La Crosse Amtrak station is located, served daily by the Empire Builder between Chicago and Seattle or Portland. In May 2024, the station added a daily round-trip on the new Borealis train between Chicago and St. Paul.[100]

Railroad tracks owned by Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway (BNSF) pass through La Crosse providing freight service. These were originally built by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad in 1886 to connect Chicago to the Twin Cities following the east bank of the Mississippi River. This line provided passenger service as well up until May 1, 1971, when Amtrak took over intercity passenger rail operations.[citation needed]

Intercity Bus

editJefferson Lines serves La Crosse with one daily bus each way running between Minneapolis and Milwaukee via Rochester and Madison.[101] In addition, Badger Bus offers service on Fridays and Sundays during the school year between Madison and Minneapolis via La Crosse.[102] Both Jefferson Lines and Badger Bus make stops at the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse Student Union, while Jefferson Lines also stops at the downtown Grand River Station transit hub.[103]

Infrastructure

editDrinking Water

editLa Crosse's tap drinking water, which is raised from a deep underground Artesian aquifer, won the best natural tasting water award in September 2007 in a statewide tasting competition hosted by the Wisconsin Water Association. The city competed against groundwater and surface water utilities from Algoma, Appleton, Green Bay, Madison, Milwaukee, Pell Lake, Shawano, Shawano Lake and Watertown at the annual meeting of the association. La Crosse's drinking water is pumped from deep ground wells to a distribution center and is treated with chlorine and fluoride; some wells are also treated with polyphosphate.[citation needed]

In recent years, the city discovered PFAS in the groundwater on French Island, WI as a result of fire fighting foam used at the La Crosse Regional Airport. This has led[when?] to the closure of two municipal wells, as well as prevented residents of parts of the Town of Campbell, WI from safely using their private wells.[104] Over 500 wells on French Island have been contaminated and the State of Wisconsin has supplied bottled water to the affected residents.[105]

Health care

editTwo major regional health care facilities are located in La Crosse: Gundersen Health System and the Franciscan Skemp Medical Center.[citation needed]

Gundersen Health System is a nationally ranked health care system located in La Crosse that is also an ACS nationally certified Level II Trauma Center. It is the primary hospital associated with the Gundersen Clinic medical group and the location of the Western campus for the University of Wisconsin Medical School. With its main campus located in La Crosse, the system also manages 23 locations throughout Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa with nearly 6,000 employees.[106][107] In 2014, Gundersen Health received the Healthgrades America's 50 Best Hospitals™ designation, placing the system among the top 1 percent of hospitals nationwide.[108]

The Franciscan Skemp Medical Center is an affiliate of the Mayo Clinic. Franciscan Skemp, which was the first western Wisconsin hospital to open its doors in 1883 as St. Francis Hospital, was started by the Catholic Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, who still are associated with the medical center. In 1995, Franciscan Skemp merged with Mayo Clinic Health Systems in Rochester, Minnesota, located 60 miles away. A new trauma and emergency department, helicopter pad, and surgery wing recently opened in 2007.[109]

The Health Science Center, located on the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse campus, is a combined effort of both medical centers, UW–La Crosse, Viterbo University, Western College, the School District of La Crosse, and various government educational groups. The purpose was to prepare and train students for advancement in the medical field.[110]

Notable people

editSister cities

editLa Crosse has sister city relationships with seven foreign towns and cities:[111]

- Bantry, County Cork, Ireland

- Dubna, Moscow Oblast, Russia

- Épinal, Vosges, Grand Est, France

- Friedberg, Bavaria, Germany

- Førde, Norway[112]

- Junglinster, Luxembourg[113]

- Kumbo, Cameroon

- Luoyang, Henan, China

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020–2022". United States Census Bureau. May 29, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Cities -". Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ "The Best Small Places For Business And Careers: La Crosse, WI". Forbes. October 24, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 17, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for La Crosse-Onalaska, WI-MN (MSA)". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. January 1, 2001. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Williams, Brad (June 10, 2022). "La Crosse ranks again in top 10 Wisconsin counties for tourism revenue". WIZM 92.3FM 1410AM. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "La Crosse: Origin of La Crosse, Wisconsin". Wisconsin Historical Society. June 9, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- ^ Coues, Elliott (1895). The Expeditions of Zebulon Montgomery Pike. Vol. 1. New York: Harper. pp. 49–51. OCLC 1045233234.

- ^ La Crosse County History: Brief History of La Crosse County, 1841–1905. La Crosse Public Library. Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mormons in Wisconsin". Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. January 2011. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013.

- ^ Charles Breck, ed. (1883). The Life of the Reverend James Lloyd Breck, D.D. New York: E. & J. B. Young.

- ^ "La Crosse". visitbluffcountry.com. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ "Annexation of Territory". Municipal Data System. Wisconsin Department of Administration. February 10, 1966. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Crandall, Jay (December 2018). "2020 Infrastructure Improvement Map". City of La Crosse. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Vian, Jourdan (December 11, 2016). "La Crosse mayors acknowledge city's inequitable past". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. p. B8 – via Newspapers.com.

The proclamation came a little over a month after Kabat apologized for La Crosse's history as a 'sundown town,' a city or village with either formal or informal codes that pushed black people out of the community after sundown, after a presentation from sociologist James Loewen at La Crosse City Hall. Loewen was invited by the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse and the city's Human Rights Commission.

- ^ "2020 Gazetteer Files". census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Hoefer, John (1985). "The Generic Use of the Term Coulee in Western Wisconsin" (PDF). The Wisconsin Geographer. 1.

- ^ "Wisconsin State Climatology Office". University of Wisconsin. 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for La Crosse, WI". University of Wisconsin. 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ "NowData: NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "Station: La Crosse Muni AP, WI". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "La Crosse/Municipal AP, WI Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "Voting Districts". City of La Crosse.

- ^ "Powell-Poage-Hamilton Neighborhood – La Crosse, WI". City of La Crosse. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ a b "Municipal Data System". DOA Division of Intergovernmental Relations. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ "2020 Decennial Census: La Crosse city, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: La Crosse city, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "Selected Social Characteristics, 2020 American Community Survey: La Crosse city, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "First Evangelical Lutheran Church in La Crosse, Wisconsin welcomes you!". First Evangelical Lutheran Church. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "Growing in Grace". Grace Evangelical Lutheran.

- ^ "Immanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church of La Crosse – WELS Synod". Immanuel Lutheran Church.

- ^ "Welcome to Mt. Calvary Lutheran Church". Mt. Calvary Evangelical Lutheran Church.

- ^ "St. John's Evangelical Lutheran Church Barre Mills". Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "EFCA Churches".

- ^ "EFCA Churches".

- ^ "Our History". Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of La Crosse.

- ^ "Why Altra?". Altra Federal Credit Union. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "La Crosse". City Brewing Company. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "Our System – Gundersen Health System". www.gundersenhealth.org. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ "Our Story". Kwik Trip. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Our History – Cargill". www.cargill.com.

- ^ Mike Tighe (August 24, 2012). "LaCrosse Footwear still in former workers' hearts". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "TRANE Our History". www.trane.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "Largest Employers (La Crosse County)". La Crosse Tribune. September 1, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "Viterbo University: Fine Arts Center History". Viterbo University Fine Arts Center. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Pump House Regional Arts Center". The Pump House.

- ^ "Staff: La Crosse Community Theatre". La Crosse Community Theatre.

- ^ Parlin, Geri (September 6, 2008). "Elmer at 80: Hand Petersen the welding torch — there's more art to create". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to Irishfest LaCrosse". April 2020..

- ^ Hatvany, Saskia (October 3, 2023). "Traditions shine as sun, warmth greet revelers". La Crosse Tribune. p. A1. Retrieved November 24, 2023 – via NewsBank.

- ^ "La Crosse Loggers: Makin' Memories... One Game at a Time!". La Crosse Loggers.

- ^ "Home - La Crosse Steam". La Crosse Steam.

- ^ "Coulee Region Chill sold and relocated to Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin". North American Hockey League. April 30, 2018.

- ^ "About Mt. La Crosse". Mt. La Crosse Skiing and Snowboarding. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ "Investing in our Facilities: UW-L Veterans Memorial Field Sports Complex". University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ "LaCrosse Fairgrounds Speedway FAQ". La Crosse Speedway. Archived from the original on January 25, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ "Riverside Park". City of La Crosse. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Tribune, Olivia Herken La Crosse (July 17, 2020). "The history behind the Hiawatha statue: What's behind the name, intent and controversy?". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Tribune, Olivia Herken La Crosse (July 22, 2020). "Petition and Ho-Chunk leaders continue discussion over Hiawatha statue in La Crosse". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "Hometown Icon: Pettibone Park". La Crosse Tribune. September 5, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ "La Crosse River Marsh: History of an Urban Wetland". La Crosse Public Library Archives. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ "Myrick Park Center & Myrick Marsh". TravelWisconsin. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ "Elected Officials". City of La Crosse. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Council's New Gang of 5 Seek Mood of Cooperation at City Hall". WXOW. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "Wisconsin presidential election results, 1964 to 2008". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. November 4, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ "Official Canvas 2012 November General La Crosse Wisconsin November 6, 2012". Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Politico Online. "Politico Wisconsin 2012 Election Results". Politico. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ Craig Gilbert (December 3, 2014). "The reddest and bluest places in Wisconsin". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Benjamin F. Bryant (ed.). Memoirs of La Crosse County from Earliest Historical Times Down to the Present. Madison, Wis.: Western Historical Association, 1907, pp. 200–201.

- ^ a b c d The Political Graveyard. Mayors of La Crosse, Wisconsin.

- ^ Usher, Ellis Baker (1914). Wisconsin: Its Story and Biography, 1848–1913, Vol. 6. Chicago: Lewis publishing Company. p. 1418.

- ^ "Photographers of Fargo – Exhibition – A. A. Bentley". Institute for Regional Studies, North Dakota State University. 2001.

- ^ "Milo Knutson, former senator dies". The Milwaukee Journal, March 22, 1981, p. 14.

- ^ "Voters Oust Mayor at La Crosse". The Milwaukee Journal, April 7, 1971, p. 13.

- ^ "A North-Sider is elected mayor: It only took 128 years". www.tmcnet.com.

- ^ 'Swantz elected Common Council President,' La Crosse Tribune. April 16, 2013.

- ^ Herken, Olivia (April 20, 2021). "Mayor Reynolds, new city council with female majority officially take office". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "School District of La Crosse Enrollment". Wisconsin's Information System for Education Data Dashboard. Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "District Facility Study Report". Google Docs. School District of La Crosse. March 1, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "Referendum". School District of La Crosse. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to Aquinas Catholic Schools". Aquinas Catholic Schools. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Providence Academy". Providence Academy.

- ^ "La Crosse Area Lutheran Schools – Elementary Schools". www.lalschools.org.

- ^ "Colleges & Universities Near La Crosse, Wisconsin | 2021 Best Schools". www.franklin.edu. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Airport". City of La Crosse. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan". City of La Crosse. Fall 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Cycle La Crosse: Economic Impact Analysis of a Better Bikeway Network in La Crosse, WI". City of La Crosse. November 8, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Drift Cycle: La Crosse Community Bike Share Project". La Crosse Neighborhoods, Inc. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Drift Cycle". Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ^ Samantha Marcus (March 2, 2008). "MTU buses cruise to 1 million served". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "La Crosse MTU: Transit System Map an Rider's Guide". City of La Crosse. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Scenic Mississippi Regional Transit Brochure" (PDF). Scenic Mississippi Regional Transit. February 1, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Glischinski, Steve (May 22, 2024). "Amtrak Borealis makes debut".

- ^ "Jefferson Lines". Jefferson Lines. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "College Connections". Badger Bus. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Bus to Wisconsin: Wisconsin Bus Stops". Jefferson Lines. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ OS Group LLC (January 21, 2021). "PFAS Contamination: Background, History & Current Understanding, La Crosse Regional Airport". City of La Crosse. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Tests show PFAS contamination in 500 French Island wells". WMTV. June 11, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ "Gundersen Health System". www.gundluth.org.

- ^ "Gundersen Health System". www.gundluth.org.

- ^ "Gundersen Health System Newsroom – Gundersen Health System". www.gundersenhealth.org.

- ^ "Home – Mayo Clinic Health System". www.mayohealthsystem.org.

- ^ "Health Science Center". La Crosse Medical Health Science Consortium.

- ^ "La Crosse: Sister Cities". City of La Crosse, Wisconsin. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ "US to copy waterfall". Aftenposten Newspaper. October 10, 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ^ "La Crosse gains 8th sister city: Junglinster, Luxembourg". January 18, 2023.

Bibliography

edit- Crocker, Leslie F. Places and Spaces: A Century of Public Buildings, Bridges and Parks in La Crosse, Wisconsin. La Crosse, Wis. 2012.

- Marcou, David J. (ed.) Spirit of La Crosse: A Grassroots History. La Crosse, Wis.: Western Wisconsin Technical College, 2000.

- Morser, Eric J. Hinterland Dreams: The Political Economy of a Midwestern City. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.