Potter Stewart (January 23, 1915 – December 7, 1985) was an American lawyer and judge who was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1958 to 1981. During his tenure, he made major contributions to criminal justice reform, civil rights, access to the courts, and Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.[2]

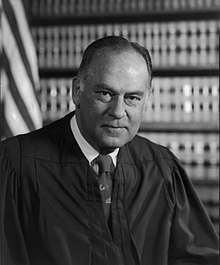

Potter Stewart | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1976 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office October 14, 1958 – July 3, 1981 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Harold Hitz Burton |

| Succeeded by | Sandra Day O'Connor |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit | |

| In office April 27, 1954 – October 13, 1958 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Xenophon Hicks |

| Succeeded by | Lester LeFevre Cecil |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 23, 1915 Jackson, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | December 7, 1985 (aged 70) Hanover, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Mary Ann Bertles (m. 1943) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Yale University (BA, LLB) University of Cambridge |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

After graduating from Yale Law School in 1941, Stewart served in World War II as a member of the United States Navy Reserve. After the war, he practiced law and served on the Cincinnati city council. In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Stewart to a judgeship on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. In 1958, Eisenhower nominated Stewart to succeed retiring Associate Justice Harold Hitz Burton, and Stewart won Senate confirmation afterwards. He was frequently in the minority during the Warren Court but emerged as a centrist swing vote on the Burger Court. Stewart retired in 1981 and was succeeded by the first female United States Supreme Court justice, Sandra Day O'Connor.

Stewart wrote the majority opinion in cases such as Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., Katz v. United States, Chimel v. California, and Sierra Club v. Morton. He wrote dissenting opinions in cases such as Engel v. Vitale, In re Gault and Griswold v. Connecticut. He popularized the phrase "I know it when I see it" with a concurring opinion in Jacobellis v. Ohio, in which a theater owner had been fined for showing a supposedly obscene film.

Early life and education

editStewart was born in Jackson, Michigan in 1915, while his family was on vacation. He was the son of Harriett L. (Potter) and James Garfield Stewart. His father, a prominent Republican from Cincinnati, Ohio, served as mayor of Cincinnati for nine years and was later a justice of the Ohio Supreme Court.[3]

Stewart earned an academic scholarship to attend the prestigious Hotchkiss School, where he graduated in 1933. He then went on to Yale University, where he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon (Phi chapter) and Skull and Bones,[4] graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1937 with a Bachelor of Arts degree cum laude. He served as chairman of the Yale Daily News. After studying international law at the University of Cambridge in England for a year, Stewart enrolled at Yale Law School where he graduated cum laude in 1941 with a Bachelor of Laws. While at Yale Law School, he was an editor of the Yale Law Journal and a member of Phi Delta Phi. Other members of that era included Gerald R. Ford, Peter H. Dominick, Walter Lord, William Scranton, R. Sargent Shriver, Cyrus R. Vance, and Byron R. White. The last would later become his colleague on the United States Supreme Court.

Stewart served in World War II as a member of the U.S. Naval Reserve aboard oil tankers from 1941 to 1945, attaining the rank of lieutenant junior grade.[5][6] In 1943, he married Mary Ann Bertles in a ceremony at Bruton Episcopal Church in Williamsburg, Virginia (at which his brother Zeph—also an initiate of Delta Kappa Epsilon and Skull and Bones, and eventually a professor of classics at Harvard—was the best man). They eventually had a daughter: Harriet (Virkstis), and two sons: Potter Jr. and David. He was in private practice with Dinsmore & Shohl in Cincinnati. During the early 1950s, he was elected to the Cincinnati City Council.

Sixth Circuit service

editStewart was nominated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on April 6, 1954, to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit vacated by Judge Xenophon Hicks. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on April 23, 1954, and received his commission on April 27, 1954. His service terminated on October 13, 1958, due to his elevation to the Supreme Court of the United States.[7]

Supreme Court

editStewart received a recess appointment from President Eisenhower as an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court on October 14, 1958,[8] to succeed Harold Hitz Burton. He took the judicial oath of office that same day.[9] He was formally nominated to the same position by President Eisenhower on January 17, 1959.[10] Public hearings were held before the Senate Judiciary Committee on April 9 and 14, 1959, and the Committee voted on May 5, 1959 to forward his nomination with a favorable report.[10] He was confirmed by the Senate in a 70–17 vote on May 5, 1959.[11] All 17 votes against his confirmation came from Southern Democrats (both senators from Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia, plus Spessard Holland of Florida).[12] He served as Circuit Justice for the Sixth Circuit from October 14, 1958 to July 3, 1981, and as Circuit Justice for the Fifth Circuit from October 12, 1971 to January 6, 1972.[7]

Stewart came to a Supreme Court controlled by two warring ideological camps and sat firmly in its center.[13][14][15] A case early in his Supreme Court career showing his role as the swing vote during that time is Irvin v. Dowd.

Stewart was temperamentally inclined to moderate, pragmatic positions,[16] but was often in a dissenting posture during his time on the Warren Court. Stewart believed that the majority on the Warren Court had adopted readings of the First Amendment Establishment Clause (Engel v. Vitale (1962), Abington School District v. Schempp (1963)), the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination (Miranda v. Arizona (1966)), and the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of Equal Protection with regard to voting rights (Reynolds v. Sims (1964)) that went beyond the framers' intention. In Engel, Stewart found no precedent to remove school sponsored prayer, and in Abington, Stewart refused to strike down the practice of school sponsored Bible reading in public schools; he was the only justice who took this position in both cases.[17] Stewart dissented in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) on the ground that, while the Connecticut statute barring the use of contraceptives seemed to him an "uncommonly silly law", he could not find a general "Right of Privacy" in the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause.

Before the appointment of Warren Burger as Chief Justice, many speculated that President Richard Nixon would elevate Stewart to the post, some going so far as to call him the front-runner. Stewart, though flattered by the suggestion, did not want again to appear before and expose his family to the Senate confirmation process. He also did not relish the prospect of taking on the administrative responsibilities that were delegated to the Chief Justice. Accordingly, he met privately with the President to ask that his name be removed from consideration.[18]

On the Burger Court, Stewart was seen as a centrist justice and was often influential. He joined the decision in Furman v. Georgia (1972), which invalidated all death penalty laws then in force, and he then joined in the Court's decision four years later, Gregg v. Georgia, which upheld the revised capital punishment legislation adopted in a majority of the states. Despite his earlier dissent in Griswold, Stewart changed his views on the right of privacy and was a key mover behind the Court's decision in Roe v. Wade (1973), which recognized the right to abortion under that right.[19] Stewart opposed the Vietnam War[20] and on a number of occasions urged the Supreme Court to grant certiorari on cases challenging the constitutionality of the war.[21]

Stewart consistently voted against claims of criminal defendants in the area of federal habeas corpus and collateral review.[22] He was concerned about broad interpretations of the Due Process and the Equal Protection Clauses.[23]

He was the lone dissenter in the landmark juvenile law case In re Gault (1967). That case extended to minors the right to be informed of their rights and the right to an attorney, which had been granted to adults in Miranda v. Arizona (1966) and Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), respectively.

In the obscenity case of Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964), Stewart wrote in his short concurrence that "hard-core pornography" was hard to define, but "I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that."[24] Justice Stewart went on to defend the movie in question (Louis Malle's The Lovers) against further censorship. One commentator opined, "This observation summarizes Stewart's judicial philosophy: particularistic, intuitive, and pragmatic."[24]

Justice Stewart commented about his second thoughts about that quotation in 1981. "In a way I regret having said what I said about obscenity—that's going to be on my tombstone. When I remember all of the other solid words I've written," he said, "I regret a little bit that if I'll be remembered at all I'll be remembered for that particular phrase."[25]

Fourth Amendment

editBefore 1967, Fourth Amendment protections were mostly limited to notions of property: possessory geographical locations such as apartments or physical objects.[26]

Stewart's opinion in Katz v. United States established that the Fourth Amendment "protects people, not places."[26] Stewart wrote that the government's installation of a recording device in a public phone booth violated the reasonable expectation of privacy since the government was committing the "seizure" of callers' words.[26] Katz therefore extended the reach of the Fourth Amendment beyond just physical intrusions and would also protect against the seizure of incorporeal words.[26] In addition, the reach of the Amendment was no longer defined solely by property limits but now went as far as a person's reasonable privacy expectation.[26] The Katz case made government wiretapping by both state and federal authorities subject to the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirements.[26]

In Chimel v. California (1969), Stewart wrote an opinion stating that arresting a suspect in his house does not give the police the right to perform a warrantless search of the entire house, only the area surrounding the arrestee.[27]

In Almeida-Sanchez v. United States (1973), Stewart wrote that roving patrols of the United States Border Patrol must have some justifiable reason before stopping a car. They could not stop and search automobiles without probable cause merely because a stop was made within 100 nautical miles (190 km) from the international border.[28]

In Whalen v. Roe (1977), Stewart, in his concurrence,[29] objected to any broad establishment of a right to privacy. He said that prior Court decisions did not "recognize a general interest in freedom from disclosure of private information."[23]

Access to courts

editJustice Stewart was a leader in trying to maintain access to federal courts in civil rights cases.[30] Stewart was one of the strongest dissenters in the trend of denying litigants access to the federal courts.[30]

Stewart wrote the Court's opinions in Sierra Club v. Morton (1972) and United States v. SCRAP (1973), broadly laying out the requirements of standing in federal actions.[30]

Civil rights

editIn Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968), Stewart extended the 1866 Civil Rights Act to outlaw private refusals to buy, sell, or lease real or personal property for racially-discriminatory reasons.[31] In 1976, Stewart extended the Act again in Runyon v. McCrary, which states that private schools open to all white students could no longer exclude black children, and all other offers to contract made to the general public were also made subject to the 1866 Act.[32]

In Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham (1965), Stewart held for the Court that police could not use an anti-loitering law to keep civil rights workers from standing or demonstrating on a sidewalk.[32]

In a dissenting opinion in Ginzburg v. United States, 383 U.S. 463 (1966), Stewart stated, "Censorship reflects a society's lack of confidence in itself. It is a hallmark of an authoritarian regime."[33]

Education

editStewart authored the concurring opinions for two very controversial cases concerning public education: San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez and Milliken v. Bradley.

In his opinion for San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, Stewart argues that while the funding method of public education is "chaotic and unjust"[34] it does not in the court's opinion, violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

His opinion for Milliken v. Bradley states that because there was no evidence of de jure segregation implemented by the school districts in the Metropolitan Detroit area, that neither the school districts nor the state of Michigan were responsible for violating the Constitutional rights of Black Detroiters and thus could not be forced to desegregate their schools. [35]

Both cases have been cited as some of the worst decisions from the court. [36][37]

Retirement and death

editStewart announced his retirement from the Court on June 18, 1981,[38] and stepped down on July 3.[9] President Ronald Reagan nominated Sandra Day O'Connor to succeed Stewart; she would become the first woman to serve on the Supreme Court.[39]

He assumed senior status upon retirement, serving in that status until his death on December 7, 1985.[7] After his retirement, he appeared in The Constitution: That Delicate Balance, a 13-episode learning course series broadcast in 1984 about the United States Constitution with Fred W. Friendly.

On January 20 and 21, 1985, Stewart administered the oath of office for Vice President George H. W. Bush. On December 7, 1985, he died from a stroke at a hospital in Hanover, New Hampshire, at the age of 70.[15][40] He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[41]

Archives

editMost of Stewart's personal and official papers are archived at the manuscript Yale University Library in New Haven, Connecticut, where they are now available for research. The files concerning Stewart's service were closed to researchers until all the justices with whom Stewart served had left the court; the last of these was Justice John Paul Stevens who considered him his judicial hero.[42] Additional papers also exist in other collections.[43]

In 1989, Bob Woodward disclosed that Stewart had been the primary source for The Brethren.[44]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Mary Ann Bertles Stewart dies, was widow of U.S. Supreme Court Justice and born in Grand Rapids". March 5, 2013. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. page 291–292.

- ^ Clare Cushman (December 11, 2012). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–2012. SAGE Publications. p. 418. ISBN 978-1-4522-3534-9.

- ^ "Six Yale Societies Elect 90 Members: Book and Snake and Berzilius Again Fill Their Ranks as University Groups. Quotas Chosen in an Hour: Tapping Is Done in the Traditional and Picturesque Harkness Court Ceremony". The New York Times. May 8, 1936. p. 18. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ "Potter Stewart (Jan. 23, 1915 - Dec. 7, 1985) » Supreme Court of Ohio". www.supremecourt.ohio.gov. Retrieved December 2, 2024.

- ^ "Stewart, Potter | Federal Judicial Center". www.fjc.gov. Retrieved December 2, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Stewart, Potter - Federal Judicial Center". www.fjc.gov. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ McMillion, Barry J. (January 28, 2022). Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2020: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McMillion, Barry J.; Rutkus, Denis Steven (July 6, 2018). "Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ "Supreme Court Nominations (1789-Present)". Washington, D.C.: United States Senate. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ "Nomination of Potter Stewart as Assoc. Justice of Supreme Court". govtrack.us. May 5, 1959. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Eisler, Kim Isaac (1993). A Justice for All: William J. Brennan, Jr., and the decisions that transformed America. page 159. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-76787-9

- ^ "Irvin v. Dowd 366 US 717 (1961)". U.S. Supreme Court. June 5, 1961. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John P. MacKenzie (December 8, 1985). "Potter Stewart is Dead at 70; Was on High Court 23 Years," NY Times Archived December 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine("The Court that Justice Stewart joined was closely divided on many of its most important questions, which often gave the junior member the deciding vote in his first few years.")

- ^ Stern, Seth (2010) Justice Brennan, Liberal Champion, page 357, Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-547-14925-5

- ^ Eisler, 182

- ^ Woodward, Bob; Scott Armstrong (September 1979). The Brethren. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-24110-9.

- ^ Eisler, 232

- ^ Strassfeld, Robert M. "The Vietnam War On Trial: The Court-Martial of Dr. Howard Levy," 1994 Wisc. L. Rev. Archived June 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine 839, 840 ("On June 19, 1974, the United States Supreme Court upheld the court-martial conviction of Dr. Howard B. Levy, and with it, the constitutional validity of Uniform Code of Military Justice ("UCMJ") Articles 1332 and 134.3 The Court's announcement of its decision in Parker v. Levy prompted an unusual display of ire; Justice Potter Stewart angrily read his dissenting opinion from the bench." [citations omitted])

- ^ Lamb, Charles M., Stephen C. Halpern, eds. (1991). The Burger Court: Political and Judicial Profiles. Champaign-Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. Chapter 6 by Phillip J. Cooper, "Justice William O. Douglas: Conscience of the Court," p. 169 ("The cases presenting challenges to the validity of the war in Vietnam came in many forms, often in litigation concerning the draft, but most of them also contained a foundation assertion that the legitimacy of the war itself was in question. Recalling this period, Douglas asserted: 'I wrote numerous opinions stating why we should take these cases and decide them. Once or twice, Potter Stewart or Bill Brennan joined me. But there was never a fourth vote.'") ISBN 0252061357, ISBN 9780252061356.

- ^ Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 296.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 304.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Potter Stewart". Oyez. Chicago-Kent College of Law. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ Al Kamen (December 8, 1985). "Retired High Court Justice Potter Stewart Dies at 70". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 292.

- ^ Chimel v. California, 395 U.S. 752 (1969)

- ^ Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 294.

- ^ Whalen v. Roe, 429 U.S. 589 (1977)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 297.

- ^ Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Pages 298–299.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Friedman, Leon. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions, Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 299.

- ^ Alternative Reel Logo – Quietly Redefining the Internet Top 10 Quotes Against Censorship.

- ^ "San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez/Concurrence Stewart - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "Milliken v. Bradley - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Journal, A. B. A. "How Did They Get It So Wrong?". ABA Journal. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "The Worst Supreme Court Decisions Since 1960". TIME. October 6, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "Justice Potter Stewart announced Thursday he is retiring". UPI. June 18, 1981. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Reagan's Nomination of O'Connor". archives.gov. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ^ AP (December 7, 1985). "Stewart, an Ex-Justice, Hospitalized by Stroke". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ "Indian Hill Historical Society, Potter Stewart". January 1, 2001. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (September 23, 2007). "The Dissenter, Justice John Paul Stevens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Biography, bibliography, location of papers on Potter Stewart Archived February 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

- ^ Lukas, J. Anthony (February 1989). "Playboy Interview: Bob Woodward". Playboy. No. 36. p. 62.

Further reading

edit- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Barnett, Helaine M., Janice Goldman, and Jeffrey B. Morris. A Lawyer's Lawyer, a Judge's Judge: Potter Stewart and the Fourth Amendment. 51 University of Cincinnati Law Review 509 (1982).

- Barnett, Helaine M., and Kenneth Levine. Mr. Justice Potter Stewart. 40 New York University Law Review 526 (1965).

- Berman, Daniel M. Mr. Justice Stewart: A Preliminary Appraisal. 28 University of Cincinnati Law Review 401 (1959).

- Cushman, Clare, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789–1995 (2nd ed.) (Supreme Court Historical Society), (Congressional Quarterly Books, 2001) ISBN 1-56802-126-7; ISBN 978-1-56802-126-3.

- Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers, 1995) ISBN 0-7910-1377-4, ISBN 978-0-7910-1377-9.

- Frank, John Paul. The Warren Court. New York: Macmillan, 1964, 133–148.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992., ISBN 0-19-505835-6; ISBN 978-0-19-505835-2.

- Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography, (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary (New York: Garland Publishing 1994). 590 pp. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1; ISBN 978-0-8153-1176-8.

- Woodward, Robert and Armstrong, Scott. The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court (1979). ISBN 978-0-380-52183-8; ISBN 0-380-52183-0. ISBN 978-0-671-24110-0; ISBN 0-671-24110-9; ISBN 0-7432-7402-4; ISBN 978-0-7432-7402-9.

- Yarbrough, Tinsley E. Justice Potter Stewart: Decisional Patterns in Search of Doctrinal Moorings. In The Burger Court: Political and Judicial Profiles, eds., Charles M. Lamb and Stephen C. Halpern, 375–406. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

External links

edit- Potter Stewart at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Biography, bibliography, location of papers on Potter Stewart at the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

- Arlington National Cemetery

- U.S. Supreme Court media on Potter Stewart at the Oyez Project

- Potter Stewart Archived April 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine at the Supreme Court Historical Society