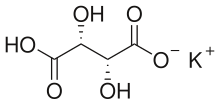

Potassium bitartrate, also known as potassium hydrogen tartrate, with formula KC4H5O6, is a chemical compound with a number of uses. It is the potassium acid salt of tartaric acid (a carboxylic acid). In cooking, it is known as cream of tartar.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Preferred IUPAC name

| |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.609 | ||

| E number | E336 (antioxidants, ...) | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| KC4H5O6 | |||

| Molar mass | 188.177 | ||

| Appearance | White crystalline powder | ||

| Density | 1.05 g/cm3 (solid) | ||

| |||

| Solubility | Soluble in acid, alkali Insoluble in acetic acid, alcohol | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.511 | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| A12BA03 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

22 g/kg (oral, rat) | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

It is used as a component of baking powders and baking mixes, as mordant in textile dyeing, as reducer of chromium trioxide in mordants for wool, as a metal processing agent that prevents oxidation, as an intermediate for other potassium tartrates, as a cleaning agent when mixed with a weak acid such as vinegar, and as reference standard pH buffer. Medical uses include as a medical cathartic, as a diuretic, and as a historic veterinary laxative and diuretic.[1]

It is produced as a byproduct of winemaking by purifying the precipitate that is deposited in wine barrels. It arises from the tartaric acid and potassium naturally occurring in grapes.

History

editPotassium bitartrate was first characterized by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742–1786).[2] This was a result of Scheele's work studying fluorite and hydrofluoric acid.[3]

Scheele may have been the first scientist to publish work on potassium bitartrate, but use of potassium bitartrate has been reported to date back 7000 years to an ancient village in northern Iran.[4] Modern applications of cream of tartar started in 1768 after it gained popularity when the French started using it regularly in their cuisine.[4]

In 2021, a connection between potassium bitartrate and canine and feline toxicity of grapes was first proposed.[5] Since then, it has been deemed likely as the source of grape and raisin toxicity to pets.[6]

Occurrence

editPotassium bitartrate is naturally formed in grapes from the acid dissociation of tartaric acid into bitartrate and tartrate ions.[7]

Potassium bitartrate has a low solubility in water. It crystallizes in wine casks during the fermentation of grape juice, and can precipitate out of wine in bottles. The rate of potassium bitartrate precipitation depends on the rates of nuclei formation and crystal growth, which varies based on a wine's alcohol, sugar, and extract content.[8] The crystals (wine diamonds) will often form on the underside of a cork in wine-filled bottles that have been stored at temperatures below 10 °C (50 °F), and will seldom, if ever, dissolve naturally into the wine. Over time, crystal formation is less likely to occur due to the decreasing supersaturation of potassium bitartrate, with the greatest amount of precipitation occurring in the initial few days of cooling.[8]

Historically, it was known as beeswing for its resemblance to the sheen of bees' wings. It was collected and purified to produce the white, odorless, acidic powder used for many culinary and other household purposes.

These crystals also precipitate out of fresh grape juice that has been chilled or allowed to stand for some time.[9] To prevent crystals from forming in homemade grape jam or jelly, the prerequisite fresh grape juice should be chilled overnight to promote crystallization. The potassium bitartrate crystals are removed by filtering through two layers of cheesecloth. The filtered juice may then be made into jam or jelly.[10] In some cases they adhere to the side of the chilled container, making filtering unnecessary.

The presence of crystals is less prevalent in red wines than in white wines. This is because red wines have a higher amount of tannin and colouring matter present as well as a higher sugar and extract content than white wines.[8] Various methods such as promoting crystallization and filtering, removing the active species required for potassium bitartrate precipitation, and adding additives have been implemented to reduce the presence of potassium bitartrate crystals in wine.[7]

Applications

editIn food

editIn food, potassium bitartrate is used for:

- Stabilizing egg whites, increasing their warmth-tolerance and volume[11]

- Stabilizing whipped cream, maintaining its texture and volume[12]

- Anti-caking and thickening[13]

- Preventing sugar syrups from crystallizing by causing some of the sucrose to break down into glucose and fructose[14]

- Reducing discoloration of boiled vegetables

Additionally, it is used as a component of:

- Baking powder, as an acid ingredient to activate baking soda[15]

- Salt substitutes, in combination with potassium chloride

A similar acid salt, sodium acid pyrophosphate, can be confused with cream of tartar because of its common function as a component of baking powder.

Baking

editAdding cream of tartar to egg whites gives volume to cakes, and makes them more tender.[16] As cream of tartar is added, the pH decreases to around the isoelectric point of the foaming proteins in egg whites. Foaming properties of egg whites are optimal at this pH due to increased protein-protein interactions.[17] The low pH also results in a whiter crumb in cakes due to flour pigments that respond to these pH changes.[16] However, adding too much cream of tartar (>2.4% weight of egg white) can affect the texture and taste of cakes.[16] The optimal cream of tartar concentration to increase volume and the whiteness of interior crumbs without making the cake too tender, is about 1/4 tsp per egg white.[16]

As an acid, cream of tartar with heat reduces sugar crystallization in invert syrups by helping to break down sucrose into its monomer components - fructose and glucose in equal parts.[18] Preventing the formation of sugar crystals makes the syrup have a non-grainy texture, shinier and less prone to break and dry. However, a downside of relying on cream of tartar to thin out crystalline sugar confections (like fudge) is that it can be hard to add the right amount of acid to get the desired consistency.

Cream of tartar is used as a type of acid salt that is crucial in baking powder.[18] Upon dissolving in batter or dough, the tartaric acid that is released reacts with baking soda to form carbon dioxide that is used for leavening. Since cream of tartar is fast-acting, it releases over 70 percent of carbon dioxide gas during mixing.

Household use

editPotassium bitartrate can be mixed with an acidic liquid, such as lemon juice or white vinegar, to make a paste-like cleaning agent for metals, such as brass, aluminium, or copper, or with water for other cleaning applications, such as removing light stains from porcelain.[19] This mixture is sometimes mistakenly made with vinegar and sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), which actually react to neutralize each other, creating carbon dioxide and a sodium acetate solution.

Cream of tartar was often used in traditional dyeing where the complexing action of the tartrate ions was used to adjust the solubility and hydrolysis of mordant salts such as tin chloride and alum.

Cream of tartar, when mixed into a paste with hydrogen peroxide, can be used to clean rust from some hand tools, notably hand files. The paste is applied, left to set for a few hours, and then washed off with a baking soda/water solution. After another rinse with water and thorough drying, a thin application of oil will protect the file from further rusting.

Slowing the set time of plaster of Paris products (most widely used in gypsum plaster wall work and artwork casting) is typically achieved by the simple introduction of almost any acid diluted into the mixing water. A commercial retardant premix additive sold by USG to trade interior plasterers includes at least 40% potassium bitartrate. The remaining ingredients are the same plaster of Paris and quartz-silica aggregate already prominent in the main product. This means that the only active ingredient is the cream of tartar.[20]

Cosmetics

editFor dyeing hair, potassium bitartrate can be mixed with henna as the mild acid needed to activate the henna.

Medicinal use

editCream of tartar has been used internally as a purgative, but this is dangerous because an excess of potassium, or hyperkalemia, may occur.[21][22]

Chemistry

editPotassium bitartrate is the United States' National Institute of Standards and Technology's primary reference standard for a pH buffer. Using an excess of the salt in water, a saturated solution is created with a pH of 3.557 at 25 °C (77 °F). Upon dissolution in water, potassium bitartrate will dissociate into acid tartrate, tartrate, and potassium ions. Thus, a saturated solution creates a buffer with standard pH. Before use as a standard, it is recommended that the solution be filtered or decanted between 22 °C (72 °F) and 28 °C (82 °F).[23]

Potassium carbonate can be made by burning cream of tartar, which produces "pearl ash". This process is now obsolete but produced a higher quality (reasonable purity) than "potash" extracted from wood or other plant ashes.

Production

editIt is produced as a byproduct of winemaking by purifying the precipitate that is deposited in wine barrels. It arises from the tartaric acid and potassium naturally occurring in grapes.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2019) |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ PubChem. "Potassium bitartrate". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ "Karl Wilhelm Scheele, Swedish chemist (1742-86)". www.1902encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Lennartson, Anders (2017), Lennartson, Anders (ed.), The Chemical Works of Carl Wilhelm Scheele, SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science, Cham: Springer International Publishing, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-58181-1, ISBN 978-3-319-58181-1, retrieved 5 December 2022

- ^ a b "Cream Of Tartar: What Is It, Anyway?". HuffPost. 19 December 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Wegenast, Colette; Meadows, Irina; Anderson, Rachele; Southard, Teresa (1 April 2021). "Letters: Unique sensitivity of dogs to tartaric acid and implications for toxicity of grapes". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 258 (7): 706–707. doi:10.2460/javma.258.7.704. PMID 33754816. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Wegenast, Colette; Meadows, Irina; Anderson, Rachele; Southard, Teresa; González Barrientos, Cristy; Wismer, Tina (23 July 2022). "Acute kidney injury in dogs following ingestion of cream of tartar and tamarinds and the connection to tartaric acid as the proposed toxic principle in grapes and raisins". Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 32 (6): 812–816. doi:10.1111/vec.13234. PMID 35869755. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ a b Coulter, A.D.; Holdstock, M.G.; Cowey, G.D.; Simos, C.A.; Smith, P.A.; Wilkes, E.N. (2015). "Potassium bitartrate crystallisation in wine and its inhibition: Cold stability". Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 21: 627–641. doi:10.1111/ajgw.12194.

- ^ a b c Marsh, G. L.; Joslyn, M. A. (1935). "Precipitation Rate of Cream of Tartar from Wine Effect of Temperature". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 27 (11): 1252–1257. doi:10.1021/ie50311a007. ISSN 0019-7866.

- ^ Max Williams at McNicol Williams Management & Marketing Services. "Lloyds Vineyard FAQs". Lloydsvineyard.com.au. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "National Center for Home Food Preservation". Uga.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ The science of good cooking : master 50 simple concepts to enjoy a lifetime of success in the kitchen (1st ed.). America's Test Kitchen. 2012. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-933615-98-1.

- ^ "How to Use Cream of Tartar". wikiHow. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ Stephens, Emily (18 February 2017). "The Incredible Cream of Tartar – How to Use and What to Substitute With". MyGreatRecipes. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ Provost, Joseph J.; Colabroy, Keri L.; Kelly, Brenda S.; Wallert, Mark A. (2016). The Science of Cooking : Understanding the Biology and Chemistry Behind Food and Cooking. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. p. 504. ISBN 9781118674208.

- ^ McGee, Harold (2004). On food and cooking : the science and lore of the kitchen (2nd ed.). Scribner. p. 533,534. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- ^ a b c d Oldham, A. M.; Mccomber, D. R.; Cox, D. F. (1 December 2000). "Effect of Cream of Tartar Level and Egg White Temperature on Angel Food Cake Quality". Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 29 (2): 111–124. doi:10.1177/1077727X00292003. ISSN 1077-727X.

- ^ Waniska, R. D.; Kinsella, J. E. (1979). "Foaming Properties of Proteins: Evaluation of a Column Aeration Apparatus Using Ovalbumin". Journal of Food Science. 44 (5): 1398–1402. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1979.tb06447.x. ISSN 0022-1147.

- ^ a b Figoni, Paula (2007). How Baking Works: Exploring the Fundamentals of Baking Science (2nd ed.). JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. ISBN 9780471747239.

- ^ "Michigan State University Extension Home Maintenance And Repair – Homemade Cleaners – 01500631, 06/24/03". Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet: Gypsum Plaster Retarder for Lime-Based Products" (PDF). USG Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Rusyniak, Daniel E.; Durant, Pamela J.; Mowry, James B.; Johnson, Jo A.; Sanftleben, Jayne A.; Smith, Joanne M. (2013). "Life-Threatening Hyperkalemia from Cream of Tartar Ingestion". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 9 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1007/s13181-012-0255-x. PMC 3570668. PMID 22926733.

- ^ Rusyniak, Daniel E.; Durant, Pamela J.; Mowry, James B.; Johnson, Jo A.; Sanftleben, Jayne A.; Smith, Joanne M. (March 2013). "Life-threatening hyperkalemia from cream of tartar ingestion". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 9 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1007/s13181-012-0255-x. ISSN 1937-6995. PMC 3570668. PMID 22926733.

- ^ Harris, Daniel C. (17 July 2006), Quantitative Chemical Analysis (7th ed.), New York: W. H. Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-7694-9