Postcoital bleeding (PCB) is non-menstrual vaginal bleeding that occurs during or after sexual intercourse.[1] Though some causes are with associated pain, it is typically painless and frequently associated with intermenstrual bleeding.[2][3]

| Postcoital bleeding | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

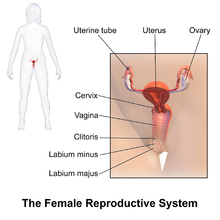

The bleeding can be from the uterus, cervix, vagina and other tissue or organs located near the vagina.[4] Postcoital bleeding can be one of the first indications of cervical cancer.[5][6] There are other reasons why vaginal bleeding may occur after intercourse. Some women will bleed after intercourse for the first time but others will not. The hymen may bleed if it is stretched since it is thin tissue. Other activities may have an effect on the vagina such as sports and tampon use.[7] Postcoital bleeding may stop without treatment.[8] In some instances, postcoital bleeding may resemble menstrual irregularities.[9] Postcoital bleeding may occur throughout pregnancy. The presence of cervical polyps may result in postcoital bleeding during pregnancy because the tissue of the polyps is more easily damaged.[10] Postcoital bleeding can be due to trauma after consensual and non-consensual sexual intercourse.[11][4]

A diagnosis to determine the cause will include obtaining a medical history and assessing the symptoms. Treatment is not always necessary.[12]

Causes

editVaginal bleeding after sex is a symptom that can indicate:

- pelvic inflammatory disease[12]

- pelvic organ prolapse

- uterine disease[13]

- chlamydia or other sexually transmitted infection[12][14][15]

- atrophic vaginitis[12]

- childbirth

- inadequate vaginal lubrication[4]

- benign polyps

- cervical erosion (inflammation of the cervix)[12][4]

- cervical or vaginal cancer[12]

- anatomical abnormality of the uterus, vagina or both.[13]

- pregnancy

- endometrial polyps

- endometrial hyperplasia

- endometrial carcinoma

- leiomyomata

- cervicitis

- cervical dysplasia

- endometriosis

- coagulation defects

- trauma[4]

Bleeding from hemorrhoids and vulvar lesions can be mistaken for postcoital bleeding.[4] Post coital bleeding can occur with discharge, itching, or irritation. This may be due to Trichomonas or Candida.[13] A lack of estrogen can make vaginal tissue thinner and more susceptible to bleeding. Some have proposed that birth control pills may cause postcoital bleeding.[6]

Risk factors for developing postcoital bleeding are: low estrogen levels, rape and 'rough sex'.[4]

Diagnosis and treatment

editTests and detailed examination are used to determine the cause of the bleeding:

- a pregnancy test

- a pelvic examination[12]

- obtaining tissue samples

- pap smear

- colposcopic examination of the vagina and cervix

- ultrasound

- histogram

- cultures for bacteria[13]

- biopsy of tissues[4]

A referral may be made to a specialist.[12][16] Imaging may not be necessary. Cryotherapy has been used but is not recommended.[4]

Epidemiology

editPostcoital bleeding rarely is associated with gynecological cancer in young women and its incidence is projected to drop due to the widespread immunizations against HPV. Postcoital bleeding has been most studied in women in the US. In a large Taiwanese study, the overall incidence of postcoital bleeding was found to be 39-59 per 100,000 women. Those with postcoital bleeding had a higher risk of cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer. Benign causes of postcoital bleeding were associated with cervical erosion, ectropion, vaginitis and vulvovaginitis. Other associations were noted such as the presence of leukoplakia of the cervix, an intrauterine contraceptive device, cervical polyps, cervicitis, menopause, dyspareunia, and vulvodynia.[17] In Scotland approximately 1 in 600 women aged 20–24 experience unexplained bleeding.[6] A study of African women found that trauma from consensual sexual intercourse was a cause of postcoital bleeding in young women.[3]

In society and culture

editHymenorrhaphy is a controversial procedure to surgically repair a damaged hymen, thus restoring the appearance of virginity:

"From a Western-ethics perspective, the life-saving potential of the procedure is weighed against the role of the surgeon in directly assisting in a deception and in indirectly promoting cultural practices of sexual inequality. From an Islamic bioethical vantage point, jurists offer two opinions. The first is that the surgery is always impermissible. The second is that although the surgery is generally impermissible, it can become licit when the risks of not having postcoital bleeding harm are sufficiently great."[18]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Ardestani, Shakiba; Dason, Ebernella Shirin; Sobel, Mara (11 September 2023). "Postcoital bleeding". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 195 (35): E1180. doi:10.1503/cmaj.230143. ISSN 1488-2329. PMC 10495171. PMID 37696551.

- ^ Smith, Roger P. (2023). "60. Postcoital bleeding". Netter's Obstetrics and Gynecology: Netter's Obstetrics and Gynecology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0-443-10739-9.

- ^ a b Boukhanni, Lahssen; Dhibou, Hanane; Zilfi, Wafaa; Housseini, Kawtar Iraki; Benkeddour, Yasser Ait; Aboulfalah, Abderrahim; Asmouki, Hamid; Soummani, Abderraouf (2016-03-25). "Les hémorragies post coïtales: à propos de 68 cas et revue de literature". The Pan African Medical Journal. 23: 131. doi:10.11604/pamj.2016.23.131.9073. PMC 4885701. PMID 27279958.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Smith, Roger P. (2017-02-16). Netter's Obstetrics and Gynecology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323523509.

- ^ Shapley, Mark; Jordan, Joanne; Croft, Peter R (2006-06-01). "A systematic review of postcoital bleeding and risk of cervical cancer". The British Journal of General Practice. 56 (527): 453–460. PMC 1839021. PMID 16762128.

- ^ a b c Health, Department of (2010-03-03). "Clinical practice guidelines for the assessment of young women aged 20-24 with abnormal vaginal bleeding". Archived from the original on 2010-11-10. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Choices, N. H. S. (2016-07-12). "Does a woman always bleed when she has sex for the first time? - Health questions - NHS Choices". Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- ^ Shapley, M; Blagojevic-Bucknall, M; Jordan, Kp; Croft, Pr (2013-10-01). "The epidemiology of self-reported intermenstrual and postcoital bleeding in the perimenopausal years". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 120 (11): 1348–1355. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12218. ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 23530690. S2CID 25418515.

- ^ Halpern, Vera; Raymond, Elizabeth G; Lopez, Laureen M (2014). "Repeated use of pre- and postcoital hormonal contraception for prevention of pregnancy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (9): CD007595. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007595.pub3. PMC 7196890. PMID 25259677.

- ^ J., Cibulka, Nancy (2013). Guidelines for nurse practitioners in ambulatory obstetric settings. Barron, Mary Lee. New York: Springer Publishing Company. p. 240. ISBN 9780826195579. OCLC 841914663.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boukhanni, Lahssen; Dhibou, Hanane; Zilfi, Wafaa; Housseini, Kawtar Iraki; Benkeddour, Yasser Ait; Aboulfalah, Abderrahim; Asmouki, Hamid; Soummani, Abderraouf (2016). "Les hémorragies post coïtales: à propos de 68 cas et revue de littérature". Pan African Medical Journal (in French). 23: 131. doi:10.11604/pamj.2016.23.131.9073. PMC 4885701. PMID 27279958.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Choices, N. H. S. (2018). "What causes a woman to bleed after sex? - Health questions - NHS Choices". Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- ^ a b c d "Postcoital Bleeding in a Premenopausal Patient". www.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 2002-04-15. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- ^ Walker, Brian R.; Colledge, Nicki R. (2013-12-06). Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780702051036.

- ^ Drake, William M.; Hutchison, Robert (2012-01-01). Hutchison's Clinical Methods, An Integrated Approach to Clinical Practice With STUDENT CONSULT Online Access,23: Hutchison's Clinical Methods. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0702040917.

- ^ "Postcoital bleeding". Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ Liu, Hsin-Li; Chen, Chuan-Mei; Pai, Lee-Wen; Hwu, Yueh-Juen; Lee, Horng-Mo; Chung, Yueh-Chin (2017-04-01). "Comorbidity profiles among women with postcoital bleeding: a nationwide health insurance database". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 295 (4): 935–941. doi:10.1007/s00404-017-4327-7. ISSN 0932-0067. PMID 28246983. S2CID 8994475.

- ^ Bawany, Mohammad H.; Padela, Aasim I. (August 2017). "Hymenoplasty and Muslim Patients: Islamic Ethico-Legal Perspectives". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 14 (8): 1003–1010. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.06.005. PMID 28760245.