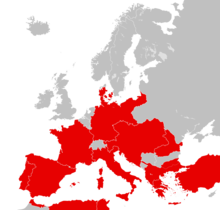

The Pork war was a ban by Germany and nine other European nations (Italy, Portugal, Greece, Spain, France, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, Romania, and Denmark) on U.S. pork imports in the 1880s.[1][2][3] Due to repeated years of low crop yield, American pork and wheat became increasingly prevalent in these countries. This angered local farmers, who soon called for boycotts. They also cited vague reports of trichinosis that supposedly originated from American pork.[4] Fueled by the growing policy of protectionism in Europe, many countries proceeded to ban all or some American pork, beef, and wheat imports. However, in 1891, after almost 20 years of economic tension, U.S. President Benjamin Harrison threatened an embargo of Germany's sugar beets, forcing Germany to allow U.S. pork imports. Other nations quickly followed suit, fearing similar repercussions.[3][2][5][6]

| Pork War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Countries in red participated in the boycott of U.S. pork. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

Background

editAfter the Franco-Prussian War and the German national unification, European imports of U.S. wheat, beef, and pork became larger and cheaper, causing local markets to crash, especially after chronic low crop yields. 1.3 billion pounds of pork at a value of $100 million was imported annually.[6] In addition, high U.S. tariffs of European manufactured goods angered European factories. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who had historically taken a protectionist standpoint on imported goods, had become convinced that that the suffering of German Industries was due in large part to free-trade practices. In addition, Germany's transformation from a food-exporting to a food-importing country, a result of Germany's rapid industrialization, was dramatically increasing the amount of U.S. meat being shipped to Europe. Because of this it was seen as necessary to both protect German Farmers and provide German industries with adequate raw materials for them to compete with foreign industries.[2][5][4]

History

editOn February 20, 1879, Italy banned pork and all pork-related imports from the U.S., claiming to have verified the arrival of Trichinae spiralis in Cincinnati-packed pork. Less than a month later, in March, Portugal joined Italy in prohibiting U.S. meat, and Greece soon followed as well. In 1880 Germany introduced a prohibition on raw American pork, but still allowed the importation of other pork products, such as bacon. While at first only sanitary reasons for the pork were cited, soon German protectionists were calling for a complete ban on all American pork products as well as American cattle. In 1882, the chancellor passed an edict prohibiting the importation of all American pork-related products, characterizing U.S. meat inspection as "unsatisfactory."[4] The conflict with Germany threatened, in the coming decade, to develop into an all-out customs war.[6] In February 1883, U.S. President Chester A. Arthur announced his intention to appoint a commission to examine the raising of hogs and the curing and packing of pork in the U.S. He also invited Germany to send their own commission of experts to join the examination, but the invitation was declined.[4][2]

Reactions to Germany's ban

editVery strong objections were made against Bismark's ban of U.S. pork (Germany previously being the second largest U.S. pork importer, after Great Britain), both in the U.S. and Germany. German economists worried that without U.S. pork, prices would increase so dramatically that pork would become inaccessible to the lower class. In the U.S., American meat packers pointed out that no decrease in the number of cases of trichinosis were reported after the ban. American newspapers, especially, took the opportunity to criticize Bismark in cartoons and articles. Newspapers and industries were particularly outraged that Germany had insisted upon banning only American pork, supposedly to injure the reputation of U.S. hog products in all other countries.[2][5] There was considerably more resentment in the United States when it became clear that Bismark intended for the ban to be permanent. During 1884 members of congress began receiving letters urging retaliatory actions, but both President Arthur and his Secretary of State, Theodore Frelinghuysen, agreed that a customs war with Germany was undesirable and that it was wisest to move slowly and with caution.[2]

The Saratoga Agreement

editTwo related developments brought about the ending of the Pork War. The first one was a bill introduced to congress in 1886 designed to please the Germans by requiring an inspection of all meats before exportation. However, no action was taken for four years until 1890, when the bill was approved, and in March 1981 congress passed an act making microscopic inspection of meat compulsory.[2][3] The second development, of considerably larger importance, was the possibility of American retaliation. According to the McKinley Tariff of October 1, 1890, the President had the power to impose a duty on German sugar beet products, which at this time were being exported to the U.S. in large quantities.[5] Because of this, an agreement was reached called "The Saratoga Agreement," in which Germany agreed to import U.S. pork and declaring that the meat had been examined and found free of disease. In return, the U.S. agreed not to take advantage of the clause in the McKinley Tariff regarding German sugar.[6] Soon after this agreement, the rest of the European nations imposing the ban revoked it, ending the conflict.

Impact

editThe Pork War had a significant impact on all countries involved. In the United States, it highlighted the growing importance of international trade on the American economy and also led to the implementation of new practices and regulations that helped American meatpackers improve the quality of their pork.[4][3]

In Germany and the rest of Europe the War marked a turning point in economic policy. It led to a shift away from protectionism and towards free trade, as German leaders realized that protectionist measures could harm their own economy as well as creating economic divides between it and its trading partners.[2]

References

edit- ^ Chalecki, Elizabeth L. (2008-03-13). "Knowledge in Sheep's Clothing: How Science Informs American Diplomacy". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 19 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/09592290801913676. ISSN 0959-2296. S2CID 154577986.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Snyder, Louis L. (1945). "The American-German Pork Dispute, 1879-1891". The Journal of Modern History. 17 (1): 16–28. doi:10.1086/236871. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 1871533. S2CID 144771257.

- ^ a b c d Hoy, Suellen; Nugent, Walter (1989). "PUBLIC HEALTH OR PROTECTIONISM? THE GERMAN-AMERICAN PORK WAR, 1880–1891". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 63 (2): 198–224. ISSN 0007-5140. JSTOR 44451379. PMID 2667661.

- ^ a b c d e Duncan, Bingham (1959). "Protectionism and Pork: Whitelaw Reid as Diplomat: 1889–1891". Agricultural History. 33 (4): 190–195. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 3740916.

- ^ a b c d Spiekermann, Uwe. "Dangerous Meat? German-American Quarrels over Pork and Beef, 1870–1900".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d Gignilliat, John L. (1961). "Pigs, Politics, and Protection: The European Boycott of American Pork, 1879–1891". Agricultural History. 35 (1): 3–12. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 3740989.