Platoon is a 1986 American war film written and directed by Oliver Stone, starring Tom Berenger, Willem Dafoe, Charlie Sheen, Keith David, Kevin Dillon, John C. McGinley, Forest Whitaker, and Johnny Depp. It is the first film of a trilogy of Vietnam War films directed by Stone, followed by Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and Heaven & Earth (1993). The film, based on Stone's experience from the war, follows a new U.S. Army volunteer (Sheen) serving in Vietnam while his Platoon Sergeant and his Squad Leader (Berenger and Dafoe) argue over the morality in the platoon and of the war itself.

| Platoon | |

|---|---|

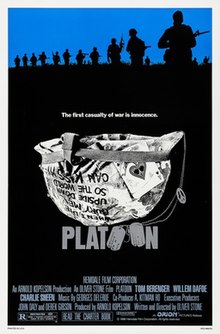

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Oliver Stone |

| Written by | Oliver Stone |

| Produced by | Arnold Kopelson |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | Claire Simpson |

| Music by | Georges Delerue |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 120 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $138.5 million[2][3] |

Stone wrote the screenplay based upon his experiences as a U.S. infantryman in Vietnam, to counter the vision of the war portrayed in John Wayne's The Green Berets. Although he wrote scripts for films such as Midnight Express and Scarface, Stone struggled to get the film developed until Hemdale Film Corporation acquired the project along with Salvador. Filming took place in the Philippines in February 1986 and lasted 54 days. Platoon was the first Hollywood film to be written and directed by a veteran of the Vietnam War.[4]

Upon its release, Platoon received critical acclaim for Stone's directing and screenplay, the cinematography, battle sequences' realism, and the performances of Sheen, Dafoe, and Berenger. The film was a box office success upon its release, grossing $138.5 million domestically against its $6 million budget, becoming the third highest-grossing domestic film of 1986. The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards at the 59th Academy Awards, and won four: Best Picture, Best Director for Stone, Best Sound, and Best Film Editing.

In 1998, the American Film Institute placed Platoon at #83 in their "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies" poll. In 2019, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[5][6][7]

Plot

editIn 1967, U.S. Army volunteer Chris Taylor arrives in South Vietnam and is assigned to an infantry platoon of the 25th Infantry Division near the Cambodian border. Though the platoon is officially under the command of the young and inexperienced Lieutenant Wolfe, the soldiers instead defer to two of his older and more experienced subordinates: the cynical Staff Sergeant Barnes, and the more compassionate Sergeant Elias.

Taylor is deployed with Barnes, Elias and other experienced soldiers for a night ambush on a North Vietnamese Army force. An NVA patrol appears, leading to a brief firefight. Taylor is wounded while another new recruit, Gardner, is killed. Upon his return to base from the aid station, Taylor bonds with Elias and his circle of marijuana smokers while remaining distant from Barnes and his more hard-edged followers.

During a subsequent patrol, two soldiers are killed by a booby trap and another by unseen assailants. Already on edge, the platoon is further angered when they discover an enemy supply cache in a nearby village. Barnes aggressively interrogates the village chief about whether the villagers have been aiding the NVA, and kills his wife when she confronts him. He then demands information from the chief while holding a gun to the head of the man's young daughter. Elias arrives and, disgusted with Barnes, attacks him. Wolfe breaks up their fistfight. He orders the supplies destroyed and the village razed. Wolfe feigns ignorance when Elias accuses him of not stopping Barnes. Taylor prevents two girls from being gang-raped by some of Barnes' men.

When the platoon returns to base, company commander Captain Harris warns he will pursue a court-martial if he finds out an illegal killing occurred, leaving Barnes concerned that Elias will testify against him. On their next patrol, the platoon is ambushed and pinned down in a firefight, and the situation is worsened when Wolfe accidentally directs an artillery strike onto his own unit before Barnes calls it off. Elias takes Taylor, Rhah and Crawford to intercept flanking enemy troops, while Barnes orders the rest of the platoon to retreat and goes back into the jungle to find Elias' group. Barnes finds Elias alone and shoots him, then tells the others that Elias is dead. While the platoon is extracting via helicopter, they see a mortally wounded Elias emerge from the jungle being chased by NVA soldiers, who eventually kill him. Noticing Barnes’ anxious response, Taylor realizes he was responsible.

Back at base, Taylor attempts to talk his group into fragging Barnes in retaliation when Barnes, having overheard them, enters the room and mocks them. Taylor then assaults Barnes but is quickly overpowered, and Barnes cuts Taylor near his eye with a push dagger before departing.

The platoon is sent back to the front line to maintain defensive positions, where Taylor shares a foxhole with another soldier named Francis. That night, a major NVA assault occurs, and the defensive lines are broken. During the battle, much of the platoon, including Wolfe and most of Barnes' followers, are killed, while an NVA sapper destroys the battalion headquarters in a suicide attack. Now in command, Captain Harris orders an air strike to expend all remaining ordnance inside the perimeter. In the chaos, Taylor encounters Barnes, who has been seriously wounded. Just as Barnes is about to kill Taylor, both men are knocked unconscious by the ferocity of Harris' air strike.

Taylor regains consciousness the following morning, picks up an enemy rifle, and finds Barnes slowly crawling along the ground. Barnes orders him to call a medic, but Taylor does not respond. Barnes dares Taylor to kill him, and Taylor immediately shoots him dead. Francis, who has survived unharmed, stabs himself in the leg reminding Taylor that because they have been twice wounded, they can return home. As a helicopter carries the two men away, Taylor waves goodbye to Rhah. Command of the platoon is given to Sgt. O'Neill, a Barnes lackey who hid under a dead body during the battle. Overwhelmed, Taylor breaks down sobbing as he flies over multiple craters full of corpses, narrating how the war has changed him forever.

Cast

edit- Charlie Sheen as Chris Taylor

- Tom Berenger as Staff Sgt. Barnes

- Willem Dafoe as Sgt. Elias

- Keith David as King

- Forest Whitaker as Big Harold

- Francesco Quinn as Rhah

- Kevin Dillon as Bunny

- John C. McGinley as Sgt. O'Neill

- Reggie Johnson as Junior

- Mark Moses as Lt. Wolfe

- Corey Glover as Francis

- Johnny Depp as Lerner

- Chris Pedersen as Crawford

- Bob Orwig as Gardner

- Corkey Ford as Manny

- David Neidorf as Tex

- Richard Edson as Sal

- Tony Todd as Warren

- Dale Dye as Captain Harris

- Paul Sanchez as Doc

Production

editDevelopment

edit"Vietnam was really visceral, and I had come from a cerebral existence: study ... working with a pen and paper, with ideas. I came back really visceral. And I think the camera is so much more ... that's your interpreter, as opposed to a pen."

The seeds of what would become Platoon began as early as 1968, months after Stone had completed his own tour of duty fighting in Vietnam. Stone first wrote a screenplay called Break, a semi-autobiographical account detailing his experiences with his parents and his time in the Vietnam War. Stone's active duty service resulted in a "big change" in how he viewed life and the war. Although Break was never produced, he later used it as the basis for Platoon.[8] His screenplay featured several characters who were the seeds of those he developed in Platoon. The script was set to music from The Doors; Stone sent the script to Jim Morrison in the hope he would play the lead. (Morrison never responded, but his manager returned the script to Stone shortly after Morrison's death; Morrison had the script with him when he died in Paris.) Although Break was never produced, Stone decided to attend film school.[8]

After writing several other screenplays in the early 1970s, Stone worked with Robert Bolt on the screenplay, The Cover-up (it was not produced). Bolt's rigorous approach rubbed off on Stone. The younger man used his characters from the Break screenplay and developed a new screenplay, which he titled Platoon. Producer Martin Bregman attempted to elicit studio interest in the project, but was not successful. Stone claims that during that time, Sidney Lumet was to have helmed the film with Al Pacino slated to star had there been studio interest.[9] But, based on the strength of his writing in Platoon, Stone was hired to write the screenplay for Midnight Express (1978).

The film was a critical and commercial success, as were some other Stone films at the time, but most studios were still reluctant to finance Platoon, because it was about the unpopular Vietnam War. After the release of The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now, the studios then cited the perception that these films were considered the pinnacle of the Vietnam War film genre as reasons not to make Platoon.[8]

Stone responded by attempting to break into mainstream direction via the easier-to-finance horror genre, but The Hand failed at the box office, and he began to think Platoon would never be made. Instead, he cowrote Year of the Dragon for a lower-than-usual fee of $200,000, on the condition from producer Dino De Laurentiis would next produce Platoon. Year of the Dragon was directed by Stone's friend Michael Cimino, who had also helmed The Deer Hunter. According to Stone, Cimino attempted to produce Platoon in 1984.[9]

The Department of Defense refused to support the production of the film due to its depiction of American war crimes, claiming the script was "rife with unrealistic and highly unfavorable depictions of the American soldier" for its depiction of the murder and rape of Vietnamese civilians by American soldiers, the attempted murder of one US soldier by another, drug abuse and portraying the majority of American soldiers as "illiterate delinquents." The film was also accused of perpetuating racist stereotypes of African-American soldiers.[10][11]

De Laurentiis secured financing for Platoon, but he struggled to find a distributor. Because De Laurentiis had already spent money sending Stone to the Philippines to scout for locations, he decided to keep control of the film's script until he was repaid.[8] Then Stone's script for what would become Salvador was passed to John Daly of British production company Hemdale. Once again, this was a project that Stone had struggled to secure financing for, but Daly loved the script and was prepared to finance both Salvador and Platoon. Stone shot Salvador first, before turning his attention to Platoon.[8]

Casting

editJames Woods, who had starred in Stone's film Salvador, was offered the role of Barnes. Despite his friendship with the director, he turned it down, later teasingly saying he "couldn't face going into another jungle with [Oliver Stone]".[12] Denzel Washington expressed interest in playing the role of Elias,[13] a character Stone said was based on a soldier he knew in Vietnam.[14] Stone confirmed in a 2011 interview with Entertainment Weekly that Mickey Rourke, Emilio Estevez and Kevin Costner were all considered for the part of Barnes. He believes Costner turned down the role "because his brother had been in Vietnam." Stone also verified in the interview that Keanu Reeves turned down the role of Taylor because of the violence.[9] Kyle MacLachlan also turned down the role of Taylor.[15] Sheen said that he got the part of Taylor, because of Dafoe's nod of approval.[16] Jon Cryer auditioned for the role of Bunny, which eventually went to Kevin Dillon.[17]

Many Vietnamese refugees living in the Philippines at the time were recruited to act in different Vietnamese roles in the film.[18]

Stone makes a cameo appearance as the commander of the 3d Battalion, 22d Infantry in the final battle, which was based on the historic New Year's Day Battle of 1968 in which he had taken part while on duty in South Vietnam. Dale Dye, who played Captain Harris, the commander of Company B, is a U.S. Marine Corps Vietnam War veteran who also served as the film's technical advisor.[19] The third US Army veteran who appears in the film is a member of the crew who was briefly seen shirtless in the climactic battle.

Filming

editExterior shooting began on the island of Luzon in the Philippines in February 1986, although the production was almost canceled because of the political upheaval in the country, due to then-president Ferdinand Marcos. With the help of well-known Asian producer Mark Hill, the shoot commenced, as scheduled, two days after Marcos fled the country.[20] Shooting lasted 54 days and cost $6.5 million. The production made a deal with the Philippine military for the use of military equipment.[8] Filming was done chronologically.[21] As a result of the Department of Defense refusing to supply historically-accurate equipment and uniforms, the film instead used equipment belonging to the Armed Forces of the Philippines.[10]

Upon arrival in the Philippines, the cast was sent on an intensive training course, during which they had to dig foxholes and were subjected to forced marches and nighttime "ambushes," which used special-effects explosions. Led by Vietnam War veteran Dale Dye, training put the principal actors—including Sheen, Dafoe, Depp and Whitaker—through an immersive 30-day military-style training regimen. They limited how much food and water they could drink and eat and when the actors slept, fired blanks to keep the tired actors awake.[22] Dye also had a small role as Captain Harris. Stone said that he was trying to break them down, "to mess with their heads so we could get that dog-tired, don't give a damn attitude, the anger, the irritation ... the casual approach to death".[8] Willem Dafoe said "the training was very important to the making of the film", adding to its authenticity and strengthening the camaraderie developed among the cast: "By the time you got through the training and through the film, you had a relationship to the weapon. It wasn't going to kill people, but you felt comfortable with it."[23]

Scenes were shot in Mount Makiling, Laguna (for the forest scenes), Cavite (for the river and village scenes), and Villamor Air Base near Manila.[24][25]

In 1986, a novelization of the film script, written by Dale Dye, was published.[26] In 2018 actor Paul Sanchez, who played Doc in the movie, made a documentary about the making of the film, entitled Platoon: Brothers in Arms.[27][28]

Soundtrack

editThe film score was composed by Georges Delerue.[29] Music used in the film includes Adagio for Strings by Samuel Barber, "White Rabbit" by Jefferson Airplane, and "Okie from Muskogee" by Merle Haggard (which is an anachronism, as the film is set in 1967 but Haggard's song was not released until 1969). During a scene in the "Underworld", the soldiers sing along to "The Tracks of My Tears" by Smokey Robinson and The Miracles, which was also featured in the film's trailer. The soundtrack includes "Groovin'" by The Rascals and "(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay" by Otis Redding.

Release

editPlatoon was released in the United States on December 19, 1986, and in the Philippines[30] and the United Kingdom in March 1987, with its release in the latter receiving an above 15 rating for strong language, scenes of violence, and soft drug use.[31]

In its seventh weekend of release, the film expanded from 214 theatres to 590 and became number one at the United States box office with a gross of $8,352,394.[32] It remained number one for four weekends.[33] In its ninth weekend, it grossed $12.9 million from 1,194 theatres over the four-day President's Day weekend, being the first film to gross more than $10 million in a weekend in February and setting a weekend record for Orion.[34]

Home media

editDue to a legal dispute between HBO Home Video and Vestron Video over home video rights, the film was delayed from its planned October 1987 release.[35] After a settlement was reached, it was finally released on tape on January 22, 1988, through HBO, and then reissued on September 1, 1988, by Vestron.[36] Vestron reissued the film twice, in 1991 and 1994. It made its DVD debut in 1997 through Live Entertainment. It was released again on VHS in 1999 by PolyGram Video (who briefly held the rights to the film through its purchase of the Epic library). The film was rereleased on DVD and again on VHS in 2001 by MGM Home Entertainment (who now owns the rights to the film through their purchase of the pre-1996 PolyGram Filmed Entertainment library).[37] MGM released the 20th anniversary DVD through Sony Pictures Home Entertainment in 2006 while 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment released the Blu-ray version on May 25, 2011. Shout! Factory released the 4K remastered Blu-Ray on September 18, 2018, and released a 4K Ultra-HD/Blu-ray combo pack on September 13, 2022.[38]

Reception

editCritical response

editOn Rotten Tomatoes, Platoon has an approval rating of 89% based on 123 reviews, with an average rating of 8.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Informed by director Oliver Stone's personal experiences in Vietnam, Platoon forgoes easy sermonizing in favor of a harrowing, ground-level view of war, bolstered by no-holds-barred performances from Charlie Sheen and Willem Dafoe."[39] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 92 out of 100, based on 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[40] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[41]

Roger Ebert gave it four out of four stars, calling it the best film of the year, and the ninth best of the 1980s.[42][43] Gene Siskel also awarded the film four out of four stars,[44] and observed that Vietnam War veterans greatly identified with the film.[45] In his New York Times review, Vincent Canby described Platoon as "possibly the best work of any kind about the Vietnam War since Michael Herr's vigorous and hallucinatory book Dispatches.[46]

"The film has been widely acclaimed," Pauline Kael admitted, "but some may feel that Stone takes too many melodramatic shortcuts, and that there's too much filtered light, too much poetic license, and too damn much romanticized insanity ... The movie crowds you; it doesn't leave you room for an honest emotion."[29]

However, black journalist Wallace Terry, who spent a two-year tour in Vietnam, and wrote the 1967 Time cover story titled The Negro in Vietnam, criticized the film for its depiction of African-American soldiers in Vietnam. In an interview with Maria Wilhelm of People, he called the film's depiction of black troops "a slap in the face". In the interview, Terry noted that there were no black actors playing officers, and the three notable black soldiers in the film were all portrayed as cowards. He further went on to criticise the film for perpetuating black stereotypes, stating the film "barely rises above the age-old Hollywood stereotypes of blacks as celluloid savages and coons who do silly things".[47] African-American veteran Bennie J. Swans described the black characters as "unable to lead and unable to follow", and said that "Millions of people are going to accept this movie as an accurate picture of blacks in the war... It re-enforces old, untrue stereotypes. That makes this a dangerous movie."[48]

Some Vietnam war veterans claimed the film perpetuated "cliché's" of American soldiers as "baby killers" and "dope addicts" and denying the use of drugs and military officers as "psychos or cowards", while others praised Stone for "telling it the way it is" regarding the depiction of the war.[49][50][51] Some veterans accused Stone of covering up war crimes he had himself witnessed as a soldier by failing to report them to his superiors, given the film was based on his autobiographical experiences.[52]

Awards and nominations

editOther honors

editAmerican Film Institute lists:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies: #83

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills: #72

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition): #86

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains: Sgt. Bob Barnes - Nominated Villain

In 2011, British television channel Channel 4 voted Platoon as the 6th greatest war film ever made, behind Full Metal Jacket and ahead of A Bridge Too Far.[53]

Video games

edit- Avalon Hill produced a 1986 wargame as an introductory game to attract young people into the wargaming hobby.[54]

- Platoon (1987), a shooter video game, was developed by Ocean Software and published in 1987–88 by Data East for a variety of computer and console gaming systems.

- Platoon (2002), also known as Platoon: The 1st Airborne Cavalry Division in Vietnam, a real-time strategy game for Microsoft Windows based on the film, was developed by Digital Reality and published by Monte Cristo and Strategy First.[55]

See also

edit- List of Vietnam War films

- Full Metal Jacket, a 1987 Vietnam War film

References

edit- ^ "Platoon". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Platoon (1986)". The Numbers. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "Platoon (1986)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ Stone, Oliver (2001). Platoon DVD commentary (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (December 11, 2019). "National Film Registry Adds 'Purple Rain', 'Clerks', 'Gaslight' & More; 'Boys Don't Cry' One Of Record 7 Pics From Female Helmers". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ "Women Rule 2019 National Film Registry". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2021-03-22. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Salewicz, Chris (1999-07-22) [1997]. Oliver Stone: The Making of His Movies (New ed.). UK: Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7528-1820-1.

- ^ a b c Nashawaty, Chris (24 May 2011). "Oliver Stone Platoon Charlie Sheen". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ a b Beckett, Jesse (2021-06-23). "Charlie Sheen's Co-Star Saved Him From Falling Out of a Heli and 7 Other Little-Known Facts About 'Platoon'". warhistoryonline. Retrieved 2024-12-29.

- ^ "Why the Pentagon didn't like 'Platoon'". August 29, 1987.

- ^ "James Woods interview: Videodrome, the Hard Way, Hercules and more". 25 February 2014.

- ^ Doty, Meriah (18 September 2012). "Denzel Washington regrets passing up 'Seven' and 'Michael Clayton'". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "How Oliver Stone's Experiences in Vietnam Influenced Platoon". YouTube. 2020-07-20. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2021-04-05.

- ^ "Kyle MacLachlan's first-ever film role was a spectacular flop. He got the last laugh". Business Insider.

- ^ Bland, Interviews by Simon (2022-01-03). "Charlie Sheen on making Platoon: 'We screamed for the medic!'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-02-15.

- ^ Cryer, Jon (5 April 2016). So That Happened: A Memoir. Penguin Publishing. ISBN 9780451472366.

- ^ Dye, Dale. "Part 3 - Confronting Demons in "Platoon"". Movies (Interview). Interviewed by Almar Haflidason. BBC. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Stone, Oliver (2001). Platoon DVD commentary (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ Depp, Johnny. "Johnny Depp: Platoon interviews". youtube. You Tube. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "Mohr Stories 84: Charlie Sheen". Mohr Stories Podcast. Jay Mohr. Aug 27, 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ "War Is Boring - From drones to AKs, high technology to low politics". War Is Boring. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ^ Chua, Lawrence. "BOMB Magazine: Willem Dafoe by Louis Morra". Bombsite.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-23. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ "Platoon filming locations". Fast rewind. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Chuyaco, Joy (4 March 2012). "Made in Phl Hollywood Films". Phil Star. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "Platoon by Dale A. Dye". Goodreads. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-07-14.

- ^ "Brothers in Arms review – Platoon's veterans hold their audience hostage". The Guardian. 2020-10-01. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ "Brothers in Arms Blu-ray Review". Blu-ray.com. 2019-09-30. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ a b Kael, Pauline (2011) [1991]. 5001 Nights at the Movies. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 586. ISBN 978-1-250-03357-4. Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Grand Opening Today". The Manila Standard. March 18, 1987. p. 15. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

A Roadshow Presentation!

- ^ "Platoon". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Domestic 1987 Weekend 5". Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Domestic Box Office Weekends For 1987". Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "'Platoon' Pumps Up February B.O.; Brisk Biz At Top". Variety. February 18, 1987. p. 3.

- ^ "Dispute Delays Video Release Of 'Platoon'". tribunedigital-chicagotribune. Archived from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ^ 'Platoon' video war ends; video due out on Friday. The Pittsburgh Press. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Peers, Benedict Carver,Martin (1998-10-22). "MGM closes in, again". Variety. Archived from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ @ShoutFactory (July 4, 2022). "Bring home the Oscar-winning PLATOON on 4K UHD 9/13. Oliver Stone's anti-war epic tells the tale of a young Army recruit sent to Vietnam who witnesses the atrocities of war – many of which are carried out by supposed "comrades."" (Tweet). Retrieved July 4, 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Platoon (1986)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ "Platoon Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on February 19, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Platoon". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1986-12-30). "Platoon Movie Review & Film Summary (1986)". Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on 2014-11-10. Retrieved 2014-11-30.

- ^ Ebert, Roger; Siskel, Gene (2011-05-03). "Siskel and Ebert Top Ten Lists (1969-1998) - Inner Mind". innermind. Archived from the original on 2020-11-08. Retrieved 2014-11-30.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (1987-01-02). "Flick Of Week: 'Platoon' Shows The Real Vietnam". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2017-09-24. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ Gene Siskel (1987-04-01). "A Test For 'Platoon': Battle Vets Say The Film Lacks Only The Taste And The Smell Of Death". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ^ "The Vietnam War in Stone's "Platoon" - New York Times". The New York Times. December 19, 1986. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Wilhelm, Maria (April 20, 1987). "An Angry Vietnam War Correspondent Charges That Black Combat Soldiers Are Platoon's M.i.a.s". People. Archived from the original on 2020-07-18. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- ^ Fordy, Tom (2020-06-15). "The problem with Platoon: why Oliver Stone's Vietnam epic made real veterans 'furious'". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2024-12-29.

- ^ "Effects of movie 'Platoon' showing up in vet centers - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved 2024-12-29.

- ^ "Oliver Stone, writer and director of 'Platoon,' the Oscar-winning... - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved 2024-12-29.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (1987-01-26). "Platoon: Viet Nam, the way it really was, on film". TIME. Retrieved 2024-12-29.

- ^ Callen, Kate (March 31, 1987). "Vietnam vet and his epic win big at Oscars". UPI.

- ^ "Channel 4's 100 Greatest War Movies of All Time". Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- ^ "Platoon (1986)". BoardGameGeek. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ "Platoon: The 1st Airborne Cavalry Division in Vietnam". GameSpot.com. 2002-11-21. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2012-10-28.