Pierre-Jean De Smet, SJ (Dutch and French IPA: [də smɛt]; 30 January 1801 – 23 May 1873), also known as Pieter-Jan De Smet, was a Flemish Catholic priest and member of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). He is known primarily for his widespread missionary work in the mid-19th century among the Native American peoples, in the midwestern and northwestern United States and western Canada.

Pierre-Jean De Smet | |

|---|---|

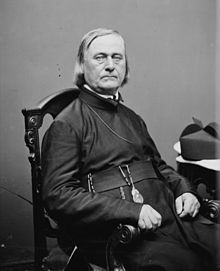

c. 1860-65, by Mathew Brady | |

| Born | 30 January 1801 |

| Died | 23 May 1873 (aged 72) |

| Other names | Pieter-Jan De Smet |

| Education | White Marsh Novitiate, present-day Bowie, Maryland |

| Church | Catholic |

| Ordained | 23 September 1827 |

His extensive travels as a missionary were said to total 180,000 miles (290,000 km). He was affectionately known as "Friend of Sitting Bull", as he persuaded the Sioux war chief to participate in negotiations with the American government for the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Native Americans gave him the affectionate nickname De Grote Zwartrok (The Great Black Skirt). [1]

Early life

editDe Smet was born in Dendermonde, in what is now Belgium in 1801, and entered the Petit Séminaire at Mechelen at the age of nineteen. De Smet first came to the United States with eleven other Belgian Jesuits in 1821, intending to become a missionary to Native Americans. He began his novitiate at White Marsh, a Jesuit estate near Baltimore, Maryland.[2] Part of the complex survives today as Sacred Heart Church in Bowie.

In 1823, De Smet was transferred to Florissant, Missouri, just north of St. Louis, to complete his theological studies and to begin his studies of Native American languages.[3] He was ordained a priest on 23 September 1827.

De Smet and five other Belgian novices, led by Charles Van Quickenborne, moved to Florissant at the invitation of bishop Louis William Valentine DuBourg. They founded several academic institutions, among which was the St. Regis Seminary, where De Smet had his first contacts with indigenous students. He learned about various Indian tribal customs and languages while serving as a prefect at the seminary.[4]

Around 1830, De Smet went to St. Louis to serve as treasurer at the College of St. Louis. On 23 September 1833, De Smet became a US citizen. He returned to Flanders that same year due to health problems and did not return to St. Louis until 1837.[4]

Mission work in Iowa Territory

editIn 1838 and 1839, De Smet helped to establish St. Joseph's Mission in what is now Council Bluffs, Iowa, in Potawatomi territory along the Upper Missouri River.[2] These people had moved west from what is now Illinois. Taking over the abandoned Council Bluffs Blockhouse at the former United States military fort, De Smet worked primarily with a Potawatomi band led by Billy Caldwell, also known as Sauganash. (Of Mohawk and Irish descent, Caldwell was born on what is now the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario. He was fluent in English and Mohawk, and some other Indian languages.) Among the women responding to Smet's request to serve the Potawatomi people was Rose Philippine Duchesne.

De Smet was appalled by the murders and brutality resulting from the whiskey trade, which caused much social disruption among the Indian people. During this time, he also assisted and supported Joseph Nicollet's efforts at mapping the Upper Midwest. De Smet used newly acquired mapping skills to produce the first detailed map of the upper Missouri River valley system, from below the Platte River to the Big Sioux River. His map shows the locations of Indian villages and other cultural features, including the wreck of the steamboat Pirate.[5][6]

First missionary tour

editwearing Order of Leopold (Belgium) decoration

After discussion with members of various Iroquois nations from the East, the Salish Native Americans had gained a slight knowledge of Christianity. At a time when their people were afflicted by illnesses, they thought the new religion might help. Three times they sent delegations of their tribe more than 1,500 miles (2,400 km) to St. Louis to request "black-robes" from the Catholic Church to come to baptize their children, sick, and dying. The first two delegations reached St. Louis after being devastated by sickness, and although Bishop Joseph Rosati promised to send missionaries when funds were available, he never did.[7] A third delegation was massacred by enemy Sioux. In 1839, a fourth delegation traveled down the Missouri River by canoe and stopped at Council Bluffs. There, they met De Smet.[2]

De Smet saw his meeting with the Salish as the will of God. He joined the delegation on its journey to St. Louis and asked Bishop Rosati to send missionaries.[7] Rosati assigned him to journey to Salish territory, to determine their nation, and to establish a mission among them. For safety and convenience De Smet traveled with an American Fur Company brigade. On 5 July 1840, De Smet offered the first Mass in Wyoming, a mile east of Daniel, a town in the west-central part of the present state. A monument to the event was later erected on this site.[8] When De Smet arrived at Pierre's Hole, 1,600 Salish and Pend d'Oreilles greeted him. He baptized 350 people and then returned to the eastern United States to raise funds for the mission.[7]

In 1841, De Smet returned to the Salish accompanied by two priests, Gregorio Mengarini and Nicholas Point, and three friars.[7] They founded St. Mary's Mission in the Bitterroot Valley among the Salish, and worked with them for several years. The following spring De Smet visited François Norbert Blanchet and Modeste Demers, missionaries at Fort Vancouver. He noted that the Protestant proselytizing of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions under Henry H. Spalding, based at Lapwai, had made the neighboring Nimíipuu (Nez Perce) nation wary of Catholicism.[9]

He persuaded a band of Nimíipuu to reside at St. Mary's for a period of two months; all of the people had received baptism before they left. Near the end of his time with the Salish, De Smet sent out an appeal to the United States public for financial aid to bolster his missionary efforts. He thought the Salish habit of seasonal nomadic movement made it "impossible to do any solid and permanent good among these poor people..."[9] He forwarded a plan proposing that the Salish "be assembled in villages—must be taught the art of agriculture, consequently must be supplied with implements, with cattle, with seed."[9] He went back to France to recruit more workers, and returned to the Pacific Northwest via Cape Horn, reaching the Columbia River on 31 July 1844 with five additional Jesuits and a group of Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur.[4]

1845-1846 Rockies expedition

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2021) |

One of De Smet's longest explorations began in August 1845 in the region west of the Rockies that was jointly occupied by the Americans, who called it Oregon Country, and the British, who identified it as Columbia District. De Smet started from Lake Pend Oreille in present-day north Idaho and crossed into the Kootenay River Valley. He followed the Kootenay valley north, eventually crossing over to Columbia Lake, the source of the Columbia River at Canal Flats.

He followed the upper Columbia valley north to and past Lake Windermere. At Radium Hot Springs, he turned east and went over Sinclair Pass into the Kootenay River Valley. He recrossed the Kootenay and continued along the reverse of the route pioneered by the Sinclair expedition. He followed the Cross River upstream to its headwaters at Whiteman's Pass. The Cross River was named for the large wooden cross that De Smet erected at the top of the pass, where it could be seen from miles away.

On the other side of the Great Divide was the British territory of Rupert's Land. From the crest of the pass, streams lead to Spray Lakes above present-day Canmore, Alberta, and the Spray River, which joins the Bow River near modern-day Banff, Alberta. Once in the Bow Valley, De Smet headed upstream and in a north-westerly direction to its source Bow Lake. He traveled further north until he came to the North Saskatchewan River, which he followed downstream and east. It was October, and a long cold winter was looming, when he reached Rocky Mountain House. He had fulfilled one of his main goals; to meet with the Cree, Chippewa, and Blackfoot of the area. At the end of the month, De Smet traveled further to the east to search for other Natives. Fortunate to find his way back to Rocky Mountain House, Natives guided him to Fort Edmonton, where he spent the winter of 1845–1846.

During these years, he established St. Mary's Mission in present-day Stevensville, Montana, among the Flathead and Kootenay Indian tribes. He also established the mission that became the Sacred Heart Mission to the Coeur d'Alene in present-day Cataldo, Idaho.[10] In the spring of 1846, De Smet began his return westward, following the established York Factory Express trade route to the Columbia District. He went west to Jasper House, and with considerable hardships completed the trek. He then crossed the Great Divide by Athabaska Pass, traveling to the Canoe_River_(British_Columbia), the northernmost tributary of the Columbia River, and eventually on to Fort Vancouver, some thousand miles (1600 km) to the southwest. He eventually arrived at his mission at Sainte-Marie on the Bitterroot River.

His book Oregon Missions and Travels over the Rocky Mountains in 1845 to 1846 was published in 1847.[1]

Later years and death

editThis section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2021) |

In 1854, De Smet helped establish the mission in St. Ignatius, Montana. It is located on the Flathead Indian Reservation. The current building was added to the National Register of Historic Places 100 years after his death. In his remaining years, De Smet was active in work related to the missions which he helped establish and fund. During his career, he sailed back to Europe eight times to raise money for the missions among supporters there. In 1868 he persuaded Sitting Bull to send a delegation to meet the U.S. peace commissioners, leading to the Treaty of Fort Laramie. De Smet returned to St. Louis and from there made several trips to the north country helping Indians and teaching Christianity. In 1850 he cruised from St. Louis to the Dakota territory aboard the steamboat Saint Agne, piloted by Joseph LaBarge. LaBarge was a close friend of De Smet, and always offered the services of his steamboat to the Catholic missionary effort.[11] De Smet died in St. Louis on 23 May 1873. He was originally buried at St. Stanislaus Seminary near Florissant, as were some fellow early Jesuit explorers. In 2003, the remains in that cemetery were moved to Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, at the newer burial site for Jesuits of the Missouri Province.

Legacy

editDe Smet's papers, with accounts of his travels and missionary work with Native American nations, are held at two separate locations:

- Jesuit Archives - De Smetiana series in St. Louis, Missouri[12]

- Pierre Jean De Smet Papers at the Washington State University archives in Pullman, Washington[13]

- De Smet was featured as a major figure in the exhibition, Crossing the Divide: Jesuits on the Frontier (26 February - 27 June 2010), held at St. Louis University Museum of Art in St. Louis.

- The exhibit A Complex Vision: De Smet and the American Frontier (17 December 2014 – 2015), at St. Louis University Museum of Art, focused on him and his work.

- In 1968, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[14]

Namesake places

editSeveral places are named in honor of De Smet, including:

- De Smet, Idaho, a populated place

- Tensed, Idaho, a populated place bordering De Smet, Idaho. The founders wanted to name their town De Smet, but when they discovered the name was taken, they chose to spell it backwards. A clerical error resulted in the "m" being changed to an "n."

- DeSmet, Montana, a populated place between Wye and the Missoula International Airport

- DeSmet Junction, near Wye, where U.S. 10, U.S. 93 and Montana Highway 200 met (and where I-90 meets them today)

- De Smet, South Dakota,[15] the later childhood home of Laura Ingalls Wilder

- De Smet Jesuit High School in Creve Coeur, Missouri

- De Smet Range and Roche de Smet in Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada

- Lake Desmet, between Buffalo and Sheridan, Wyoming

- DeSmet Hall, the largest and oldest all-men's residence hall on the Gonzaga University campus in Spokane, Washington.

- DeSmet Hall, First Year residence hall at Regis University campus in Denver, Colorado

See also

edit- Red Fish, Oglala chief

References

edit- ^ "Deze Vlaamse pater zat nog met Chief Sitting Bull aan tafel".

- ^ a b c Fanning, William. "Pierre-Jean De Smet." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 21 June 2019 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Literary St. Louis. St. Louis, Missouri: Associates of St. Louis University Libraries, Inc. and Landmarks Association of St. Louis, Inc. 1969.

- ^ a b c Davis, William L., "De Smet, Pierre-Jean", Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003

- ^ a b Whittaker (2008): "Pierre-Jean De Smet’s Remarkable Map of the Missouri River Valley, 1839: What Did He See in Iowa?", Journal of the Iowa Archeological Society 55:1-13

- ^ Mullen, Frank. (1925) "Father De Smet and the Pottawattamie Indian Mission", Iowa Journal of History and Politics 23:192-216.

- ^ a b c d Baumler, Ellen (Spring 2016). "A Cross in the Wilderness: St. Mary's Mission Celebrates 175 Years". Montana The Magazine of Western History. 66 (1): 19–21. JSTOR 26322905. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Official State Highway Map of Wyoming (Map). Wyoming Department of Transportation. 2014.

- ^ a b c Smet, Pierre. Origin, Progress, and Prospects of the Catholic Mission to the Rocky Mountains. Fairfield, Washington: Ye Origin Galleon Press, 1972. pp. 9-11.

- ^ Eberlein, Jake A., Wilderness Cathedral: The Story of Idaho’s Oldest Building, Mediatrix Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0692897652

- ^ Chittenden, 1905, Vol. II, p. 62

- ^ "De Smetiana". jesuitarchives.org. 21 May 2014.

- ^ "Guide to the Pierre Jean De Smet Papers 1764-1970 (bulk 1821-1873) Cage 537". ntserver1.wsulibs.wsu.edu. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 105.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Pierre-Jean De Smet". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Sources

edit- Killoren, John J. 'Come, Blackrobe': De Smet and the Indian Tragedy, The Institute of Jesuit Sources (2003), reprint of the University of Oklahoma Press (1994); ISBN 1-880810-50-6

- ——; Richardson, Alfred Talbot; De Smet, Pierre-Jean (1905). Life, letters and travels of Father Pierre-Jean de Smet, S.J., 1801-1873, Volume II. New York : Francis P. Harper.

External links

edit- Works by Pierre-Jean De Smet at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Peter John De Smet, S.J. (1801 - 1873) ~ Life and times of a Blackrobe in the West

- The Apostle of the Rocky Mountains: Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J., Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Pierre-Jean De Smet at Find a Grave

- Pieter-Jan De Smet in ODIS - Online Database for Intermediary Structures