In Greek mythology, Pholus (Ancient Greek: Φόλος) was a wise centaur and friend of Heracles who lived in a cave on or near Mount Pelion.[1]

Biography

editIt is well known that Chiron, the famously civilized centaur, had origins which differed from those of the other centaurs. Chiron was the son of Cronus and a minor goddess Philyra, which accounted for his exceptional intelligence and honor, whereas the other centaurs were bestial and brutal, being the descendants of Centaurus who is the result of the unholy rape of a minor cloud-goddess that resembled Hera by the mortal king Ixion. Where Chiron was immortal and could die only voluntarily, the other centaurs were mortal like men and animals.

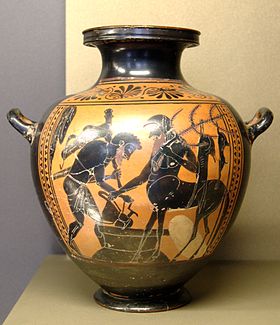

Pholus, like Chiron, was civilized, and indeed in art sometimes shared the "human-centaur" form in which Chiron was usually depicted (that is, he was a man from head to toe, but with the center and hindparts of a horse attached to his buttocks). This form was of course used to differentiate Chiron and Pholus from all other centaurs, who were mostly represented as men only from the head to the waist, and therefore more animal-like.

To further account for the unusually civil behavior of Pholus, the mythographer Apollodorus wrote that his parents were Silenus and one of the Meliae,[2] thus differentiating him genealogically from the other centaurs, as Chiron was known to be. This different parentage apparently did not carry with it immortality, however, and Pholus died just as the other centaurs.

Encounters with Heracles

editThe differing accounts vary in details, but each story contains the following elements: Heracles visited his cave sometime before or after the completion of his fourth Labor, the capture of the Erymanthian Boar. When Heracles drank from a jar of wine in the possession of Pholus, the neighboring centaurs smelled its fragrant odor and, driven characteristically mad, charged into the cave. The majority were slain by Heracles, and the rest were chased to another location (according to the mythographer Apollodorus, Cape Maleas) where the peaceful centaur Chiron was accidentally wounded by the arrows of Heracles which were soaked in the venomous blood of the Lernaean Hydra. In most accounts, Chiron surrendered his immortality to be free from the agony of the poison when it came to helping Hercules free Prometheus.

While this pursuit and second combat was occurring, Pholus, back in his cave, accidentally wounded himself with one of the venomous arrows[3] while he was either marveling at how such a small thing could kill a centaur (Apollodorus)[4] or preparing the corpses for burial (Diodoros).[5] He died quickly as a result of the poison's extreme virulence, and was found by Heracles.

Hyginus (in his De Astronomia) reports versions of the story where it is not Pholus's foot on which the poison arrow accidentally falls, but Chiron's instead.[6]

In the Divine Comedy poem Inferno, Pholus is found with the other centaurs patrolling the banks of the river Phlegethon in the seventh circle of Hell.

Namesake

editThe city of Pholoe in ancient Arcadia was named after him.[7]

Notes

edit- ^ Gantz, pp. 390–392.

- ^ Apollodorus, 2.5.4; Gantz, pp. 139, 392.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 147, 392.

- ^ Apollodorus, 2.5.4.

- ^ Diodoros, 4.12.3–8.

- ^ Gantz, p. 392.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, Ph670.3

References

edit- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Online version by Bill Thayer

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).