Lebensphilosophie (German: [ˈleːbm̩s.filozoˌfiː]; meaning 'philosophy of life') was a dominant philosophical movement of German-speaking countries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which had developed out of German Romanticism. Lebensphilosophie emphasised the meaning, value and purpose of life as the foremost focus of philosophy.[1]

Its central theme was that an understanding of life can only be apprehended by life itself, and from within itself. Drawing on the critiques of epistemology offered by Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, notable ideas of the movement have been seen as precursors to both Husserlian phenomenology and Heideggerian existential phenomenology.[1]

Lebensphilosophie criticised both mechanistic and materialist approaches to science and philosophy[1] and as such has also been referred to as the German vitalist movement,[2] though its relationship to biological vitalism is questionable. Vitality in this sense is instead understood as part of a biocentric distinction between life-affirming and life-denying principles.[3]

While often rejected by academic philosophers, it had strong repercussions in the arts.[4]

Overview

editThis philosophy pays special attention to life as a whole, which can only be understood from within. The movement can be regarded as a rejection of Kantian abstract philosophy or scientific reductionism of positivism.

Inspired by the critique of rationalism in the works of Arthur Schopenhauer, Søren Kierkegaard[according to whom?], and Friedrich Nietzsche, Lebensphilosophie emerged in 19th-century Germany as a reaction to the Age of Enlightenment, rise of positivism and the theoretical focus prominent in much of post-Kantian philosophy.[1][5][6] As such, Lebensphilosophie is defined as form of irrationalism, as well as a form of Counter-Enlightenment.[7][6] Twentieth-century forms of Lebensphilosophie can be identified with a critical stress on norms and conventions.[8]

The first elements of a Lebensphilosophie are found in the context of early German Romanticism which conceived existence as a continuous tension of "the finite towards the infinite", an aspiration that was always disappointed and generated either a withdrawal into oneself and detachment with an attitude of pessimistic renunciation, or on the contrary exaltation of the instinctive spirit or vital impulse of the human being, a struggle for existence or a religious acceptance of the destiny of man entrusted to divine providence.[6]

Wilhelm Dilthey was the first to seek to account for a "pre-theoretical cohesion of living", by taking the phenomenological turn and relying on the historical experience of life, by highlighting relationships specific to life (Lebensbezüge), that Martin Heidegger would later considered both as a fundamental step, but also insufficiently radical.[9] The Lebensphilosophie movement bore indirect relation to the subjectivist philosophy of vitalism developed by Henri Bergson, which lent importance to immediacy of experience.[10]

An early systematic presentation was formulated by the German psychologist Philipp Lersch, who, while primarily studying Bergson, Dilthey and Spengler, saw Georg Simmel and Ludwig Klages as Lebensphilosophie's most important representatives.[11]

Philosopher Fritz Heinemann considered the Lebensphilosophie as an intermediate stage in the transition from the philosophy of spirit to the philosophy of existence.[12] Georg Misch, Dilthey's student and son-in-law, worked out the relationship between the philosophy of Martin Heidegger and Edmund Husserl and the Lebensphilosophie in 1930.[13]

Characteristics and schools

editCharacteristics that regularly recur in the work of Lebensphilosophie thinkers, although not in every writer, can be summarized as follows:[14][15]

- Life is central: in contrast to empiricism and materialism on the one hand, which place matter central, or idealism and rationalism on the other, which place intellect central, the philosophy of life wants to explain the world from the perspective of life.

- Biology and historicism is central: while earlier philosophers often gave physics a central role in their thinking, this role is assigned to biology by philosophers of life, including Henri Bergson, or history by Wilhelm Dilthey.

- Anti-mechanism thought: life and broader reality should not be understood as a machine, but rather as an evolving and creative process. The philosophy of life is therefore closely linked to the thesis of vitalism, which states that life must be explained by means of a special urge to live that is inherent to life itself.

- Actualism: according to the philosophy of life, reality lacks any form of stability and must instead be understood as a continuous process of change, movement, becoming and life.

- Irrationalism: the philosophy of life also has its own philosophy of science in which a general aversion to reasonable laws, concepts and logical deductions applies. (Scientific) reason is not capable of fully understanding reality. Life and reality, on the other hand, must be understood from intuition or practical experience.

- Realism: Philosophers of life, unlike idealists, adhere to a form of realism, which means that they believe that the world exists independently of human thought.

- Immanence: Another characteristic is the aversion to the urge for transcendence and the emphasis on immanence. Man should not focus his gaze on possible structures, principles or concepts that transcend man, but should focus on the here and now; man should not long for another, better and higher world, but should place this world centrally.

- Aphoristic style: The insights of the philosophy of life are often also written down in an aphoristic or literary style. This is partly due to the conviction that the true insights of life cannot be captured in a theoretical framework. Furthermore, the texts of the philosophy of life were also often characterized by their high literary quality and the absence of philosophical jargon. This can be found in the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, the aphoristic writing style of Friedrich Nietzsche and work of Henri Bergson, which earned him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1927.[16]

Additionally, Lebensphilosophie can be divided into following different schools:[17]

- Bergsonism or the doctrine of the urge to live, found in Henri Bergson and Maurice Blondel.

- Historicism that emphasizes the dynamic role of history, found in Wilhelm Dilthey and Georg Simmel.

- German lebensphilosophie that had a strong populist and irrationalist character, found in Hermann Graf Keyserling and Ludwig Klages.

The infinite in the finite

editThe Lebensphilosophie tries to make sense of an continuous and unresolved clash between "the infinite and the finite", that is shown in the incessant fading of living beings. The questions that the Lebensphilosophie poses find a first answer in the fifteen lectures held in 1827 in Vienna by Friedrich Schlegel who sees the nucleus of divine revelation in the highlighting of the infinite in the finite of man.

Referring to this romantic vision, both Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, with completely different results, exalt the active character of life, contrasting it with the staticity of idealistic perfection of rationalism.

Schopenhauer reveals the essential irrationality of living that manifests itself in the will to live (German: Wille zum Leben) , the senseless noumenal essence of everything in the world that has the sole purpose of increasing itself.

Nietzsche conceives life as a continuous growth and overcoming of those values consolidated over time that would hypocritically try to normalize existence in current morality. Life, in Nietzsche's thought, contrary to Darwinism, is never adaptation, conservation, but continuous growth without which the living being dies. The typical attempt of humanity to found its life on certainties, seeking them in religion, science, moral values, causes it to die out, overwhelmed by the proverbial "modern culture".

Precursors

editThe roots of the Lebensphilosophie go back to the distinction made by Immanuel Kant with regard to Christian Wolff; between theoretical school philosophy and a philosophy based on the concept of the world, which comes from life itself and is aimed at practical life.

Other individuals associated with the earliest forms of "Lebensphilosophie" were Johann August Ernesti and Johann Georg Heinrich Feder.[18]

At the end of the 18th century, life and world wisdom were fashionable terms in higher social circles.The philosophy of life was less a specific philosophical doctrine than a certain cultural mood that influenced large parts of the intelligentsia.

Lebensphilosophie was equated with the popular philosophy that was widespread in the late 18th century, which deliberately distanced itself from school philosophy and, as a philosophy of practical action, was committed to the general dissemination of the ideas of the Enlightenment.[19]

Since then, the wisdom of life and the world has often been presented in aphorisms, for example by Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi in the Ffliegen Blätter: "Philosophy is an inner life. A philosophical life is a concentrated life. Through true philosophy the soul becomes still, and ultimately devout."[20]

In terms of the history of the concept, the first works to be recorded are those of Gottlob Benedict von Schirach: On Human Beauty and the Philosophy of Life from 1772 and Karl Philipp Moritz: Contributions to the Philosophy of Life from 1780 (already in its third edition in 1791). Characteristics of Lebensphilosophie are attributed to verse from Goethe's Faust[21]; "All theory, dear friend, is gray, but the golden tree of life springs ever green."[22]

The Lebensphilosophie found new inspiration in Sturm und Drang movement, as well as the Romantic movement. Romantics such as Novalis emphasized that not only reason, but also the feelings and wills that are more closely related to life, must be taken into account in philosophy. "Philosophy of life contains the science of independent, self-made life, which is in my own power - and belongs to the doctrine of the art of living - or the system of rules for preparing such a life for oneself."[23] In 1794, Immanuel Kant opposed this type of “salon philosophy” in his essay Über den Gemeinspruch: Das mag in der Theorie richtig sein, taugt aber nicht für die Praxis.

In 1827, Friedrich Schlegel's lectures on the Lebensphilosophie, which were explicitly directed against the "system philosophers" Kant and Hegel, helped the philosophy of life to gain wider attention. Schlegel viewed the formal concepts of school philosophy, such as logic, as merely preparation, not as philosophy itself. To him, philosophy must mediate between the philosophy of reason and natural science. That it is important to explore "the inner spiritual life, and indeed in all its fullness" and that the "interpreting soul" encompasses the full consciousness and not just reason. [24]

The interpreting soul, however, includes both the distinguishing, connecting, deductive reason, as well as the pondering, inventing, presaging imagination; it encompasses both forces, standing in the middle between them. But it also forms the turning point of the transition between understanding and will, and, as the connecting middle link, fills the gap that lies between the two and separates them.

History and representatives

editIt was not until the second half of the 19th century until Lebensphilosophie could be tangibly identified as a real movement. It nevertheless contained many of the ideas that were already present in the predecessors, but radicalized and extrapolated them and developed them into a fully-fledged philosophy through the efforts of a noted thinkers.

Lebensphilosophie's emergence is contributed to Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which resulted in an proverbial "biologization" of man and society; in which everything began to be interpreted in terms of survival and natural selection (i.e. social Darwinism). Man was no longer seen as a being that was completely different from animals, but only as one of them, although he was often placed higher on the evolutionary ladder. This opened the door to the Lebensphilosophie, which had to expand this tendency and extend it to all areas of reality.[26]

The other factor that paved the way for Lebensphilosophie was the situation at German universities in the second half of the 19th century. The German government then decided to impose strict censorship on German universities. However, this also affected philosophy, in the sense that only the philosophy accepted by the state was allowed to be disseminated and philosophy was limited to epistemology and logic.

However, the German public also needed another philosophy, an ethics or metaphysics, a philosophy that could be a guideline for life. In order to fill this void, a group of philosophers emerged in Germany who developed their own philosophy independently of academic thinking. Philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche are the prime examples of this.

Schopenhauer had indeed received a philosophical education, but only taught philosophy for a short time, when he was not yet famous. He lived off his inheritance and therefore never really had to work; he himself stated that he lived for philosophy and not from philosophy. Nietzsche was not even a philosopher by training, but a philologist and never gave a lecture on philosophy. The thinking of these precursors of the philosophy of life reached the public through their writings, which are notable for their absence of philosophical jargon and were distributed outside of academic circuits. [27]

Thirdly, the political factor is also important, namely in political defeats, as with the case of Germany after the First World War, had their repercussions in philosophy. The German defeat led to a revival of the so-called German Lebensphilosophie, which in turn also had its influence on the rise of National Socialism.[10]

Friedrich Nietzsche, Wilhelm Dilthey and Henri Bergson are considered to be the founders of Lebensphilosophie[28], with Max Scheler writing the first overview of the Lebensphilosophie in 1913, in which he pointed out the similarities between Nietzsche, Dilthey and Bergson.[29]

Arthur Schopenhauer

editThe main precursor and source of inspiration for the Lebensphilosophie was the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. He made the first approaches to formalizing Lebensphilosophie, when he no longer placed reason, but will - thusly actual life - at the centre of his thinking. Seeing that the will is the primary basis of ideas, which is a blind, unstoppable urge that encompasses all of nature. Reason and knowledge are dependent on it and are an expression of the will, with the entire life force of the world being reflected in the will.[30]

Since the will, the thing in itself, the inner content is the essence of the world; life, the visible world, the appearance, is only the mirror of the will; this will accompany the will as inseparably as its shadow accompanies the body: and if there is will, life, the world will also exist. The will to live is therefore certain of life.

His philosophy is largely set out in his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation. In it, Schopenhauer voiced his criticism towards idealistic philosophers - such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Hegel - whom he accused of placing too much emphasis on reason and intellect. Schopenhauer himself was a follower of Kant and retained his distinction between the "thing as we see it" and the "Thing-in-itself". That the reality in itself is unknowable and is inaccessible to our senses.

Schopenhauer, however, also states that there is another way to know the "Thing-in-itself": if one looks into oneself, one experiences that man is nothing more than the expression of an all-encompassing Will that lies hidden behind all phenomena. Reality as we experience it is therefore in fact only an illusory veil that lies over reality as it really is: in reality the world is nothing other than a World Will that, without any rational principle, continually produces new phenomenal manifestations, such as man, in order to express its own will. The world is therefore anything but rational and benign, and reason is certainly not central. The world is indifferent to man, and man himself is primarily a "willing" being: he continually desires things, without rational grounds, but only on the basis of emotions and drives.

On chapter 46 of The World as Will and Representation, entitled "On the Nothingness and Suffering of Life," Schopenhauer describes man as a suffering and lost individual who only finds salvation through death. Man lives in a constant desire with limitless wishes and inexhaustible demands, so that he can never find happiness and salvation. If a wish is fulfilled, it immediately becomes unreal and only grief and pain remain. In this way, human life is nothingness, emptiness (vanitas) and vanity, covered by the deceptive veil of Maya. In earthly life, man can only escape this emptiness through abstinence and asceticism, the highest form of which, complete contemplation, can be found in art. Schopenhauer's additional reflections on the practice of life can be found in the aphorisms on the Parerga and Paralipomena.

Friedrich Nietzsche

editThe thought of Friedrich Nietzsche is also considered a forerunner of the Lebensphilosophie. Nietzsche was a follower of Schopenhauer, was known for his skepticism towards reason, science, culture and the modern ideal of the search for truth.

Throughout his work, Nietzsche developed ideas that are considered to be inspiration for the Lebensphilosophie, such as a view of world events as an organic structure and the concepts of the will to power and the eternal return. Nietzsche turned Schopenhauer's concept of the will as the will to live into the formula of the will to power, which dominates all life.

Already in his early work The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche established that the human condition is determined by a contradiction between two different forces: on the one hand, the reasonable and calm Apollonian force and on the other, the exuberant and wasteful Dionysian force; an contradiction that he also observed present in the classical Greek tragedy. Nietzsche explicitly connected the Dionysian force with Schopenhauer's metaphysical Will.

In ancient Greece there was a good balance between both principles. However, this was disturbed by the ancient philosophy of Socrates and Plato. They rejected the Dionysian side of life and focused only on the Apollonian side, a shift that can be found throughout the history of Western philosophy.[32]

Nietzsche also called for getting rid of the too rationalistic side of life because it mainly results in a denial of life itself. Traditional philosophers praise the ascetic life as the highest form of life, but according to Nietzsche this is only a denial of the creative and dynamic power that life possesses.

In his work, Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche states that:

Saying yes to life even in its strangest and hardest problems; the will to live, finding joy in the sacrifice of its highest types of its own inexhaustibility - I called that Dionysian, I guessed that was the bridge to the psychology of the tragic poet.

Nietzche also determined that there is no transcendental world to mirror ourselves in or to direct ourselves towards (after death); there is only this world and this life. All this is reflected in his well-known propositions such as "God is dead" and the "eternal recurrence" from his 1882 work, The Gay Science.

The death of God implied the loss of any kind of transcendental orientation, and the idea of eternal return can serve as a new guideline for life: live in such a way that you would want it to return again and again. There was also the concept of "will to power": man, life, and even all of reality does not strive for things like "the good" or "the truth", but rather only for more power.

Historicism

editLargely due to the influence of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, the early modern form of Lebensphilosophie emerged in Germany near the end of the 19th century. The initial movement was known as "historicism", which was primarily presented by Wilhelm Dilthey, Rudolf Eucken and Georg Simmel.

One noted progenitor was Wilhelm Dilthey, in whose works the notion of "life" or "human experience" is central. He strongly opposed the deterministic philosophy of nature as defended by John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer. Human experience always involves experiencing a coherence; a coherence that cannot be divided into scientific "atoms" or basic elements.

Dilthey argued that there was a difference between the natural sciences and the human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften). In the natural sciences, the scientist "explains" and refers to the causes (erklären). In the human sciences, however, the scientist "understands": in a hermeneutic process, the scientist must place the concept in a broader historical context in order to gain insight into it (Verstehen). In this Verstehen, knowledge is not a product of the mind, but rather an outgrowth of the emotions and will of the person in question. According to Dilthey, both disciplines therefore require a different epistemological approach. The classical mechanistic model of natural science is therefore unsuitable for understanding life and human history.

With this idea in mind, Dilthey proposed hermeneutics as a scientific method for the human sciences. The historian or sociologist must always see a certain (historical) fact in relation to the whole, the context in which it took place and at the same time understand the whole on the basis of the different parts. However, hermeneutics is not limited to the written word, but can also be applied to other areas such as art, religion or law.

Dilthey's philosophy gained many followers, mainly in cultural philosophy, including Hans Freyer, Theodor Litt, Georg Misch, Erich Rothacker, Oswald Spengler and Eduard Spranger. Dilthey also had a strong influence on the theologian Ernst Troeltsch and the British philosopher R.G. Collingwood.[34]

The philosopher and sociologist Georg Simmel agreed with Kant when he stated that human cognition possesses a priori categories of thought, but argued that these undergo a development. The categories are therefore not a timeless given that is eternally fixed, but on the contrary they can evolve over time, both at the level of humanity and at the level of the individual. Human perception, together with these categories, ensures that the chaos of sensory impressions that man receives, is ordered. However, the human mind is not able to grasp reality in its entirety: thus "the truth" is separate from the human mind. According to Simmel, "truth", or what man considers to be truth, determines behavior. What is true is therefore determined by means of natural selection through the evolution of man, and thus largely by the utility that particular view has.

According to Simmel, "moral must" is also originally a category of human reason that is only "formally" determining, but the content of what must and what may change throughout history. In this moral must, the will of the sex is also expressed: altruism is understood by Simmel, for example, as egoism of the sex.

19th century and early 20th century

editThe philosophical movement of Lebensphilosophie at the end of the 19th century began clearly distinguishing itself from the definition that "Philosophy of Life" meant in the late 18th century 100 hears prior, which was to provide orientation for practical life. This new form of Lebensphilosophie critically examined modern epistemology and ontology and seek to gain a systematic standpoint.

Lebensphilosophie became a part of the reaction towards the contemporary zeitgeist, which was characterized by the rapid progress of technology, industrialization and the rationality of the positive sciences and the modern economy. It found support within the fin de siècle, the German youth movement and Art Nouveau, along with the Symbolism movement and/or Decadent movement, all sharing the need to find a "new beginning" against the constraints of modern civilization.

In France, at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, a series of philosophers emerged who defended similar life-philosophical ideas. The first philosophers to take up the fight against the mechanism and idealism of the 19th century were Maurice Blondel and Édouard Le Roy. Blondel, for example, already set out his version of the Lebensphilosophie in his 1893 work "L'Action", with the development of the "philosophy of action". Other French philosophers - such as Émile Boutroux, Jules Lachelier and Félix Ravaisson-Mollien - are also associated with the early French-strain of Lebensphilosophie.

However, it was not until the philosophy of Henri Bergson that French Lebensphilosophie took on its definitive form and had a strong influence on the further course of French philosophy. In his philosophy he expounded a strong form of vitalism and anti-mechanism. Bergson had been a follower of Herbert Spencer's philosophy in his early thinking, but later renounced this kind of philosophy because he found Spencer's philosophy much too mechanistic.

He expounded his own thinking mainly in four works, each covering an area of his philosophy of life: first being Time and Free Will, in which he expounded his theory of knowledge, Matter and Memory, detailing his views on psychology, Creative Evolution, detailing his views on metaphysics, and The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, in which Bergson expounds his ethics and philosophy of religion.

According to Bergson, there are two different ways of knowing the world, which arise from a fundamental contradiction in man himself. Just as we can conceive of time as either a mathematical series of successive points or a continuous flow (durée) that we experience, we can also know the objects around us according to these two methods: analysis on the one hand and intuition on the other. Analysis essentially means that one reduces the object one wants to know to more fundamental parts that are already known.

However, Bergson argues that in this way one is not really dealing with reality, but isolating some repeatable aspects of it. Classical movements such as idealism and/or rationalism place this form of knowledge central, while analysis according to Bergson can never penetrate reality itself, but can at most play a role in our practical dealings with the world. In contrast, there is knowledge through intuition. Through intuition, man can understand the world in itself without reducing it to something else. Bergson conceives the contrast between the two methods as analogous to the two ways in which one can describe the movements of our actions: either we perceive our action from within as a whole, or we can describe it from without, but then it falls apart into smaller parts and is by definition incomplete. Bergson also sees this method of analysis at work in the sciences, which is why he shows a certain contempt for science.[35]

In his 1907 work, Creative Evolution, Bergson argued that the two classical models to explain life, the mechanical and teleological models, were wrong. They do not take into account duration (durée). Starting from his epistemology he argued that both currents wrongly mirror themselves on reason instead of intuition.

In contrast, life must be understood as a life stream that follows its own creative, irrational path through reality. Life cannot be explained by mechanisms or final causes, but has its own life drive (élan vital) that brings it into being and drives it forward. Life has followed an ascending path through plants and animals in its history, ultimately resulting in man. In man, in addition to reason, intuition also emerged and thus the possibility of truly understanding reality. This dynamic and creative interpretation is not limited to life, however, but covers everything: the whole of reality is evolution. In reality, there are no 'things', only actions and becoming.

Towards the end of Bergson's career, various philosophers emerged who supported his philosophy and even radicalized it. So much so that the movement can be identified as "Bergsonism". Examples of this is a whole series of Catholic thinkers such as Léon Ollé-Laprune, Lucien Laberthonnière and Alfred Loisy.

Interwar period and German Lebensphilosophie

editFollowing the defeat of Germany at the end of First World War, a new school of Lebensphilosophie emerged, which had its influence primarily in biology, but also in politics. The main thinkers who belonged to this school were Hans Driesch, Karl Joel, Hermann Graf Keyserling and Ludwig Klages.

Largely under the influence of post-World War I pessimism, they associated reason and intellect with the shortcomings of "civilization" and therefore advocated a rejection of intellectualism. Instead, they focused their attention primarily on the irrational forces of life and lust. This largely resulted in an equation of nature and culture and a biological interpretation of society. This is said to have contributed to the rise of National Socialist racism.[10][7][8]

Hans Driesch, a philosopher and biologist, concluded from a number of experiments in which bacteria were split and only new bacteria were formed, that life could not be a product of causal natural forces, but instead had to be understood in the light of entelechy. That behind living matter there is an immaterial force that purposefully creates and supports life. Driesch was therefore considered one of the main representatives of vitalism.

Ludwig Klages, on the other hand, emphasized the contrast between the unity of body and soul on the one hand and the human spirit or reason on the other. This contrast is also reflected in the title of his main work, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, released 1929-1932.

According to Klages, soul and body are inseparable and if the soul could work undisturbed, then man would see the world as a continuous stream of images. However, through the action of the spirit and human reason, the illusion is created that body and soul can be separated from each other. According to Klages, the natural science that emphasizes this division is therefore a danger to life itself. As a result, Klages adopted a strongly irrationalist position and was very hostile to human reason. Partly because of this, his teaching was influential within Nazi ideology.[7]

Influence

editThe Lebensphilosophie was very popular in the first half of the 20th century, but quickly lost its following after the Second World War. Its initial popularity can be understood by the fact that it emerged as an alternative to the then dominant scientific and positivist philosophy. Positivism denied the relevance of an ethic or philosophy of life and emphasized epistemology and science. The Lebensphilosophie broke with this tradition and wanted to make philosophy relevant again for "the life of the man on the street".

It's quick dissipation following the second world war is believed to be due to the associations that this type of philosophy had leading to Nazism and fascism, which also appealed to similar biological, vitalistic and irrational elements. Additionally, other philosophical movements, such as existentialism, overtook Lebensphilosophie.

The ideas of the Lebensphilosophie have entered many other contemporary movements, which often rejected the "irrational" character of the Lebensphilosophie. The philosopher Otto Friedrich Bollnow for example, claims to be a follower of the Lebensphilosophie developed by Dilthey, but also connects this movement with insights from existentialism and phenomenology. The work of José Ortega y Gasset, and especially his 1930 work The Revolt of the Masses, also contains many elements from the Lebensphilosophie and is strongly influenced by the perspectivism of Friedrich Nietzsche.

The direct influence of Lebensphilosophie thinkers on academic philosophy remained limited, despite their great popularity with the masses, mainly because of their hostility to reason and science. Instead, someone like Bergson had an influence on other genres, such as writers like Marcel Proust and political scientists like Charles Péguy and Georges Sorel.[32]

Only after the Second World War, when the Lebensphilosophie lost importance, did Henri Bergson's influence also become clear in academic philosophy. Later thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Maurice Merleau-Ponty often contrasted their views with those of Bergson in order to expose the differences, but in doing so they nevertheless betrayed the influence that Bergson had exerted on their work. Traces of the Lebensphilosophie can also be recognized in the work of Max Scheler and Martin Heidegger.

This is even more explicit in the work of the French poststructuralist Gilles Deleuze, who characterized himself as a "vitalist". In 1966, Deleuze wrote a book, "Le Bergsonisme", which revived the study of Bergson's work. Furthermore, the Lebensphilosophie can also be found in the form of concepts such as biopolitics and biopower in the work of Michel Foucault or Giorgio Agamben.[18]

In 1993, Ferdinand Fellmann attempted to rehabilitate the Lebensphilosophie, after it had been rejected as a "disturbance in philosophy" due to the ideological abuse by National Socialism. According to Fellmann, human self-understanding is not only the product of a "Cartesian cogito", but must also take into account the irrational physical and emotional aspects of human existence. He also points out that contemporary analytical philosophy and the philosophy of mind are also influenced by the Lebensphilosophie.

Association with American pragmatism

editAlthough the American movement of pragmatism is often seen as an independent movement, it has many similarities with the Lebensphilosophie.[36] For example, pragmatism and the Lebensphilosophie are often placed together under the heading of "anti-intellectualism". This is mainly due to the work of William James and John Dewey and is present to a much lesser extent in the work of C.S. Peirce.[37]

James' philosophy, which incorporated numerous influences from various movements, explicitly referred to the work of Bergson.[38] The two philosophers, Bergson and James, were also good friends and his well-known concept of consciousness as a stream of consciousness shows a strong affinity with Bergson's concept of duration (durée).

As a bridge between pragmatism and Lebensphilosophie, the so-called "dialectical school" should also be mentioned. This school consisted of a number of thinkers, such as Ferdinand Gonseth and Gaston Bachelard, grouped around the philosophical journal Dialectica, founded in 1947. They stated that truth was always dialectical and therefore a temporary and changeable given. For the dialectical school too, there was no absolute truth separate from practical life itself.

Criticism

editBefore the second world war, Lebensphilosophie drew derision from neo-Kantian and rationalist thinkers, such as Heinrich Rickert[39] and Ernst Cassirer.[40] Following the second world war, various studies have found links between Lebensphilosophie and Nazism.[7][8][additional citation(s) needed]

Irrationalism

editA reproach often made against Lebensphilosophie is that of irrationalism. Some Lebensphilosophie philosophers endorse the irrationalist element in their philosophy, but critics find this unacceptable. To give up reason as a means to truth means to give up philosophy and even thought as a whole.

For example, Bertrand Russell states in his 1946 book A History of Western Philosophy that according to Lebensphilosophie; "intellect is the misfortune of man, while instinct is seen at its best in ants, bees, and Bergson" and concludes that for "those to whom action, if it is to be of any value, must be inspired by some vision, by some imaginative foreshadowing of a world less painful, less unjust, less full of strife than the world of our every-day life, those, in a word, whose action is built on contemplation, will find in this philosophy nothing of what they seek, and will not regret that there is no reason to think it true."[41]

This criticism is also shared by George Santayana.[42] He states that Lebensphilosophie is a symptom of a spiritually impoverished imagination, that in it; "the mind has forgotten its proper function, which is to crown life by quickening it into intelligence, and thinks if it could only prove that it accelerated life, that might perhaps justify its existence."[43]

In his 1953 book, The Destruction of Reason, Marxist philosopher Georg Lukács also strongly criticized the Lebensphilosophie and characterized it as an extreme form of irrationalism, which served as a method to justify the ruling ideology of the "imperialist bourgeoisie" (i.e. bourgeois nationalism).[7]

Vitalism

editAnother criticism is that the principle of vitalism, which is upheld by the Lebensphilosophie, namely that there is a kind of life force behind life, contains circular reasoning.

Relativism

editOther philosophers accuse the Lebensphilosophie of falling into a form of relativism.[44] Because certain knowledge is no longer possible, due to the irrationalist nature of the Lebensphilosophie, it is impossible to provide any form of criticism of ideas, because one would then have to use reason anyway. The result is that all ideas and visions would then be of equal value.

This stems from Wilhelm Dilthey's hermeneutics and historicism - which laid the basis of Lebensphilosophie - being already scrutinized for being of relativistic thought.[45] If ideas or institutions have to be assessed in the specific historical context in which they exist, it is always possible to shield these ideas from any form of criticism. Criticism of an idea is then interpreted as the failure to correctly understand the idea in its specific context. Every idea is correct, as long as it is understood within the specific historical context in question.

Connection to Nazism

editIn Germany the corresponding school [to vitalism], known as Lebensphilosophie ("philosophy of life"), began to take on aspects of a political ideology in the years immediately preceding World War I. The work of Hans Driesch and Ludwig Klages, for example, openly condemned the superficial intellectualism of Western civilization. In associating "reason" with the shortcomings of "civilization" and "the West", Lebensphilosophie spurred many German thinkers to reject intellection in favour of the irrational forces of blood and life. In the words of Herbert Schnädelbach, at this point "philosophy of life tendentiously abolished the traditional difference between nature and culture and thus facilitated the success of the general biologism in the theory of culture, which culminated in National Socialist racism."

In his 1953 book, The Destruction of Reason, having concluded that Lebensphilosophie merely represented irrationalism from the standpoint of the "imperialist bourgeoisie", Georg Lukács also concluded that it was an ideological development towards Nazism. Lukács saw Ludwig Klages in particular as the forerunner of fascism, having "transformed [German vitalism] into an open attack on reason and culture." He additionally pointed to Oswald Spengler and his work (primarily The Decline of the West) being a key part in “reconstructing [German vitalism] as a philosophy of militant reaction” following the first world war, resulting in a “veritable, direct prelude to fascist philosophy.”[7]

Intellectual historian Carl Müller Frøland concluded that Lebenphilosophie movement experienced an "Völkisch-Ideological Turn", which formed the ideological basis for the Nazism. He saw that the biopolitical vitalism of Lebenphilosophie was easily connected with social Darwinist thought, with an co-current strain of Nietzchean-style vitalism mixed with Völkisch nationalism rising within Imperial Germany. At outbreak of the first world war, these ideas fused into a proverbial "war-worshipping vitalism", which was an progenitor of Nazism.[46]

The Israeli-American historian Nitzan Lebovic identified Lebensphilosophie with the tight relation between a "corpus of life-concepts" and what the German education system came to see, during the 1920s, as the proper Lebenskunde, the 'teaching of life' or 'science of life'—a name that seemed to support the broader philosophical outlook long held by most biologists of the time. In his book Lebovic traces the transformation of the post-Nietzschean Lebensphilosophie from the radical aesthetics of the Stefan George Circle to Nazi or "biopolitical" rhetoric and politics.[8]

Frederick C. Beiser, in his book Philosophy of Life: German Lebensphilosophie 1870-1920 found that Nazis had appropriated some of its themes to their ideology. However, Beiser notes that "there is really very little in common" between national socialism and Lebensphilosophie thought.[47]

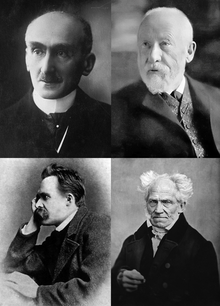

List of notable theorists

editSee also

edit- Absurdity

- Henri Bergson

- Wilhelm Dilthey

- Essence

- Existence

- Existential crisis

- Ferdinand Fellmann

- Viktor Frankl

- German Idealism

- Pierre Hadot

- Human situation

- Hans Jonas

- Søren Kierkegaard

- Meaning of life

- Self-discovery

- Vitalism

- German Idealism, an antecedent philosophical movement to Lebensphilosophie[5]

- German Romanticism, an antecedent intellectual movement to Lebensphilosophie

- Lebensreform

- Dark Enlightenment

- People indirectly associated with the Lebensphilosophie movement

- Henri Bergson, notable for his studies of immediate experience

- Hannah Arendt, notable for her distinction between vita activa and vita contemplativa

- Pierre Hadot, notable for his conception of ancient Greek philosophy as a bios or way of life

- Giorgio Agamben, notable for his zoe–bios distinction

References

edit- ^ a b c d Gaiger, Jason (1998). "Lebensphilosophie". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge.

- ^

- "Ludwig Klages". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 March 2024.

Klages was a leader in the German vitalist movement (1895–1915),

- "Klages, Ludwig (1872–1956)". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved September 26, 2020 – via Encyclopedia.com.

Klages was the principal representative in psychology of the vitalist movement that swept Germany from 1895 to 1915.

- "Ludwig Klages". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 March 2024.

- ^

- Sprott, W. J. H. (1929). "Review: The Science of Character by Ludwig Klages; W. H. Johnson". Mind. New Series. 38 (152). Oxford University Press: 513–520. doi:10.1093/mind/XXXVIII.152.513. JSTOR 2250002.

- Lebovic, Nitzan (2006). "The Beauty and Terror of Lebensphilosophie: Ludwig Klages, Walter Benjamin, and Alfred Baeumler". South Central Review. 23 (1). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 23–39. doi:10.1353/scr.2006.0009. S2CID 170637814.

- ^ Cf. Manos Perrakis (ed.), Life as an Aesthetic Idea of Music. Universal Edition, Vienna/London/New York, NY 2019 (Studien zur Wertungsforschung 61), ISBN 978-3-7024-7621-2.

- ^ a b Michael Friedman, A Parting of the Ways: Carnap, Cassirer, and Heidegger, Open Court, 2013.

- ^ a b c Ruggiano, Michele (1981). L'infinito nella sensibilità romantica (in Italian). University of California: G. Ricolo.

- ^ a b c d e f Lukács, György (1981) [1953]. "Chapter IV. Vitalism (Lebensphilosophie) in Imperialist Germany". The Destruction of Reason. Humanities Press. ISBN 9780391022478.

- ^ a b c d Nitzan Lebovic, The Philosophy of Life and Death: Ludwig Klages and the Rise of a Nazi Biopolitics, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- ^ Introduction dans Le jeune Heidegger 1909-1926, VRIN, coll. « Problèmes et controverses », 2011v, p. 19

- ^ a b c d Wolin, Richard. "Continental philosophy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

In Germany the corresponding school [to vitalism], known as Lebensphilosophie ("philosophy of life"), began to take on aspects of a political ideology in the years immediately preceding World War I. The work of Hans Driesch and Ludwig Klages, for example, openly condemned the superficial intellectualism of Western civilization. In associating "reason" with the shortcomings of "civilization" and "the West", Lebensphilosophie spurred many German thinkers to reject intellection in favour of the irrational forces of blood and life. In the words of Herbert Schnädelbach, at this point "philosophy of life tendentiously abolished the traditional difference between nature and culture and thus facilitated the success of the general biologism in the theory of culture, which culminated in National Socialist racism."

- ^ Philipp Lersch: Contemporary Philosophy of Life, Munich 1932, reprint in: Philipp Lersch: Horizons of Experience. Writings on the Philosophy of Life, edited and introduced by Thomas Rolf, Albunea, Munich 2011, 41–124

- ^ Fritz Heinemann: New Paths of Philosophy. Mind, Life, Existence. An Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy, Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1929, and Fritz Heinemann: VIVO SUM. Fundamental Remarks on the Meaning and Scope of Life Philosophy. In: New Yearbooks for Science and Youth Education, 9 (Issue 2/1933), 113–126

- ^ Georg Misch: Philosophy of Life and Phenomenology. A discussion of Dilthey’s movement with Heidegger and Husserl. [1931], 2nd edition. Teubner, Leipzig/ Berlin 1931.

- ^ Bochenski, I.M (1974) [1947]. Contemporary European Philosophy. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-00133-8.

- ^ Jean-Claude Gens, L'Herméneutique diltheyenne des mondes de la vie, Revue Philosophie n 108, hiver 2010, p. 67-69.

- ^ "Nobel Prize in Literature 1927". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ Bochenski, I.M (1974) [1947]. Contemporary European Philosophy. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-00133-8.

- ^ a b Nitzan Lebovic, "The Beauty and Terror of "Lebensphilosophie": Ludwig Klages, Walter Benjamin, and Alfred Baeumler", South Central Review, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Wilhelm Traugott Krug: Allgemeines Handwörterbuch der philosophischen Wissenschaften, nebst ihrer Literatur und Geschichte. Band 2, Brockhaus 1827, Stichwort: Lebensphilosophie. Zur Popularphilosophie siehe: Christoph Böhr: Die Popularphilosophie der deutschen Spätaufklärung im Zeitalter Kants. frommann-holzboog, Stuttgart 2003.

- ^ Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi: Fliegende Blätter. In: Werke. 6 Bände, Leipzig 1812–1827 (Nachdruck: Band VI, Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1968, page 136).

- ^ Lüer, Renja (2013) [1992]. Goethes Faust als Lebensphilosophie: Teil 1: Faust - eine (Lebens-)Tragödie?. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 9783656382980.

- ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust I, 2038 f

- ^ Novalis Schriften. Die Werke Friedrich von Hardenbergs. Historisch-kritische Ausgabe (HKA) in vier Bänden. Band II, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1965–1975, page. 599.

- ^ Friedrich Schlegel: Philosophie des Lebens. In fünfzehn Vorlesungen gehalten zu Wien im Jahre 1827. Kritische Ausgabe seiner Werke. Band 10, p. 1–308,

- ^ Friedrich Schlegel: Philosophie des Lebens. In fünfzehn Vorlesungen gehalten zu Wien im Jahre 1827. Kritische Ausgabe seiner Werke. Band 10, p. 1–308,

- ^ Frøland, Carl Müller (2020). Understanding Nazi Ideology: The Genesis and Impact of a Political Faith. McFarland, Incorporated. ISBN 9781476637624.

- ^ Magnus, Bernd; Higgins, Kathleen Marie, eds. (1996). The Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780521367677.

- ^ Albert, Karl (1995). Lebensphilosophie: Von den Anfängen bei Nietzsche bis zu ihrer Kritik bei Lukács (Kolleg Philosophie) (in German). K. Alber. p. 9. ISBN 9783495478264.

- ^ Max Scheler: Attempts at a Philosophy of Life, first in: Die weissen Blätter, 1st year, No. III (Nov.) 1913, republished with additions in: Max Scheler: Vom Umsturz der Werte, 1915, republished as 4th edition by Maria Scheler, Francke, Berlin and Munich 1972, 311–339

- ^ Arthur Schopenhauer: Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. Werke in fünf Bänden (Ausgabe letzter Hand), hrsg. von Ludger Lütkehaus. Band 1, Haffmans, Zürich 1988, S. 362.

- ^ Arthur Schopenhauer: Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. Werke in fünf Bänden (Ausgabe letzter Hand), hrsg. von Ludger Lütkehaus. Band 1, Haffmans, Zürich 1988, S. 362.

- ^ a b Wolin, Richard. "Continental philosophy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche: Götzendämmerung. Was ich den Alten verdanke § 5, KSA 6, 160

- ^ Bochenski, I.M (1974) [1947]. Contemporary European Philosophy. University of California Press. p. 124-125. ISBN 0-520-00133-8.

- ^ Kołakowski, Leszek (1985). Bergson. Oxford University Press. p. 42-46. ISBN 9780192876454.

- ^ Bochenski, I.M (1974) [1947]. Contemporary European Philosophy. University of California Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-520-00133-8.

- ^ Gallie, W.B. (1975) [1952]. Peirce and Pragmatism. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 14. ISBN 9780837183428.

- ^ Gallie, W.B. (1975) [1952]. Peirce and Pragmatism. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 24. ISBN 9780837183428.

- ^ Heinrich Rickert: The Philosophy of Life. Presentation and Critique of the Philosophical Fashions of Our Time [1920], 2nd ed. Mohr, Tübingen 1922

- ^ Ernst Cassirer: Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. Part III: Phenomenology of Knowledge. (1929), reprint of the 2nd edition 1954, WBG, Darmstadt 1982, p. 46.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2004) [1945]. A History of Western Philosophy, and Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Taylor & Francis. p. 716. ISBN 9781134343669.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Noël (1992). Santayana - Thinkers of Our Time (2 ed.). Claridge Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1870626330.

- ^ Santayana, George (1968). Henfrey, Norman (ed.). Selected Critical Writings of George Santayana Volume 2 (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0521094641.

- ^ Bollnow, Otto Friedrich (2009). Boelhauve, Ursula (ed.). Lebensphilosophie und Existenzphilosophie. Königshausen & Neumann. p. 142. ISBN 9783826041860.

- ^ Wolfgang, Röd (1976). Geschichte der Philosophie,, Beck'sche Elementarbücher, Vol. 3 / Die Philosophie des ausgehenden 19. und des 20. Jahrhunderts. C.H.Beck. p. 127. ISBN 9783406492754.

- ^ Frøland, Carl Müller (2020). Understanding Nazi Ideology: The Genesis and Impact of a Political Faith. McFarland, Incorporated. p. 95-96. ISBN 9781476637624.

- ^

Beiser, Frederick C. (March 21, 2023). "Introduction". Philosophy of Life: German Lebensphilosophie 1870-1920. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780192899781.

Lebensphilosophie. Some of its themes were appropriated by the Nazis, who tried to make them the philosophy of their movement.[...] Yet there is really very little in common between national socialism and Lebensphilosophie. The aggressive hypernationalism, racism, and imperialism characteristic of Nazism have no precedent in Lebenphilosophie.

Further reading

edit- William James and other essays on the philosophy of life, Josiah Royce

- Existential philosophy, Paul Tillich

- Reconsidering Meaning in Life

- Philosophy of Life in Contemporary Society

External links

edit- Academic journals