Pedro Pablo Kuczynski Godard[a] (Latin American Spanish: [kuˈtʃinski ɣoˈðaɾð];[b] born 3 October 1938), also known simply as PPK (Spanish: [pepeˈka]), is a Peruvian economist, public administrator, and former politician who served as the 59th President of Peru from 2016 to 2018. He served as Prime Minister of Peru and as Minister of Economy and Finance during the presidency of Alejandro Toledo. Kuczynski resigned from the presidency on 23 March 2018, following a successful impeachment vote and days before a probable conviction vote.[1] Since 10 April 2019 he has been in pretrial detention, due to an ongoing investigation on corruption, money laundering, and connections to Odebrecht, a public works company accused of paying bribes.[2]

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski | |

|---|---|

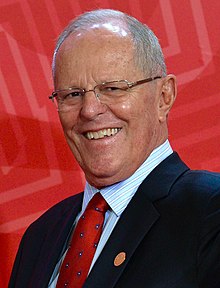

Kuczynski in 2016 | |

| 59th President of Peru | |

| In office 28 July 2016 – 23 March 2018 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Ollanta Humala |

| Succeeded by | Martín Vizcarra |

| Prime Minister of Peru | |

| In office 16 August 2005 – 28 July 2006 | |

| President | Alejandro Toledo |

| Preceded by | Carlos Ferrero |

| Succeeded by | Jorge del Castillo |

| Minister of Economy and Finance | |

| In office 16 February 2004 – 16 August 2005 | |

| President | Alejandro Toledo |

| Prime Minister | Carlos Ferrero |

| Preceded by | Jaime Quijandría |

| Succeeded by | Fernando Zavala |

| In office 28 July 2001 – 12 July 2002 | |

| President | Alejandro Toledo |

| Prime Minister | Roberto Dañino |

| Preceded by | Javier Silva Ruete |

| Succeeded by | Javier Silva Ruete |

| Minister of Energy and Mines | |

| In office 28 July 1980 – 3 August 1982 | |

| President | Fernando Belaúnde Terry |

| Prime Minister | Manuel Ulloa Elías |

| Preceded by | René Balarezo |

| Succeeded by | Fernando Montero |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Pedro Pablo Kuczynski Godard 3 October 1938 Lima, Peru |

| Nationality |

|

| Political party | Modern Force (since 2024) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4, including Alex |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Jean-Luc Godard (cousin) |

| Alma mater | Exeter College, Oxford (BA) Princeton University (MPA) |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Official website |

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski was born in the Miraflores District of Lima to parents who fled from Germany after the Nazis came to power. Kuczynski worked in the United States before entering Peruvian politics.[3] He held positions at both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund before being designated the general manager of Peru's Central Reserve Bank. He later served as Minister of Energy and Mines in the early 1980s under President Fernando Belaúnde Terry, and as Minister of Economy and Finance and prime minister under President Alejandro Toledo in the 2000s.[4] Kuczynski was a presidential candidate in the 2011 presidential election, placing third. His opponents Ollanta Humala and Keiko Fujimori went on to the 5 June 2011 runoff election, in which Humala was elected.[5] Kuczynski went on to stand in the 2016 election, where he narrowly defeated Fujimori in the second round.[6] He was sworn in as president on 28 July 2016.[7][8]

On 15 December 2017, the Congress of Peru, which was controlled by the opposition Popular Force, initiated impeachment proceedings against Kuczynski, after he was accused of lying about receiving payments from the scandal-hit Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht in the mid-2000s.[9] However, on 21 December 2017, the Peruvian Congress lacked the majority of votes needed to impeach Kuczynski.[10] After further scandals and facing a second impeachment vote, Kuczynski resigned from the presidency on 21 March 2018 following the release of videos showing alleged acts of vote buying, presenting his resignation to the Council of Ministers.[11][12] He was succeeded as president by his First Vice President Martín Vizcarra. On 28 April 2019, Kuczynski was placed under house arrest while under investigation for allegedly taking bribes from Odebrecht.[13]

Early life and education

editKuczynski was born in Miraflores, Lima, Peru, as the first son of Madeleine (née Godard) and Maxime Hans Kuczyński, one of the earliest public health leaders in Peru.[14][15][16] He is a cousin of the French film director and critic Jean-Luc Godard.[17]

His parents fled Germany in 1933 to escape from Nazism. His father, born in Berlin, then capital city of the German Empire, was a German Jew of distant Polish origin, and his mother was Protestant, of Swiss-French descent.[18] Entering Peru in 1936, Maxime Kuczyński sent his son to be educated first in Lima at Markham College, and then in Lancashire in England at Rossall School, where he was a pupil in the Maltese Cross House between 1953 and 1956. He won a foundation scholarship to study at Exeter College, Oxford, and graduated with a degree in politics, philosophy and economics in 1960. Later, he received the John Parker Compton fellowship to study public affairs at Princeton University in the United States, where he received a master's degree in 1961. He began his career at the World Bank in 1961 as a regional economist for six countries in Central America, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.[19]

In 1967, Kuczynski returned to Peru to work at the country's central bank during the presidency of Fernando Belaúnde. Kuczynski went into exile in the United States in 1969 due to political persecution after Belaunde's government fell to the military dictatorship of General Juan Velasco Alvarado in a coup d'état. The newly installed government accused Kuczynski of funnelling about $18 million (equivalent to $115 million in 2016) to Nelson Rockefeller’s International Petroleum Company. He joined the World Bank as the chief economist managing the northern countries of Latin America, moving on to become Chief of Policy Planning.[20]

From 1973 to 1975, Kuczynski was a partner at Kuhn, Loeb & Co.,[21] an international investment bank headquartered in New York City. In 1975, he returned to Washington, D.C. to become Chief Economist of the International Finance Corporation, the private finance arm of the World Bank. Subsequently, he was appointed President of Halco Mining in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a mining consortium with operations in West Africa.[22]

From 1983 to 1992, Kuczynski was co-chairman of First Boston in New York City, an international investment bank. In 1992, he founded, with six other partners, the Latin American Enterprise Fund (LAEF) in Miami, Florida, a private equity firm that focused on investments in Mexico, Central and South America. The institutional investors in LAEF included more than 15 of the world's largest university endowments, foundations, and pension funds. In 1983, he helped found the Inter-American Dialogue and remained a member until 1997.[23]

Early political career

editInvolvement in politics

editIn 1980, following the election of Fernando Belaúnde Terry as president, Kuczynski was invited to return to Peru to serve as Minister of Energy and Mines. In this position, he sponsored Law 23231 which, through tax exemptions and other incentives, promoted oil and gas exploration and exploitation after a period of relative neglect. Kuczynski resigned in 1982 and returned to the private sector in the United States. During the second round of the 2016 presidential campaign, he claimed that he had left Peru due to the threats and attacks from the Shining Path insurgent group: "Let's remember that the terrorists not only hung my effigy on the zanjón (a local denomination for Paseo de La República avenue in Lima) and in San Martín square, but they attacked my apartment. Just as 3 million Peruvians, I left the country". This was in response to an attack by election opponent Keiko Fujimori (daughter of then-imprisoned former president Alberto Fujimori and main rival of PPK in the second round of elections) who claimed that Kuczynski did not "have moral authority to speak of terrorism".[24]

During the rest of the 1980s and 1990s, Kuczynski was mainly involved in the private equity and fund management business in the United States. He made small personal donations to the presidential campaigns of George H. W. Bush and of George W. Bush, and to the state-senator campaign of his wife's cousin in Wisconsin. He additionally made donations to New York Senator Chuck Schumer and New Jersey Senator Bill Bradley.[25]

In 2000, Kuczynski joined the presidential campaign of Alejandro Toledo, then an economics professor at the ESAN University in Lima. After Toledo was elected president in the 2001 Peruvian general election, Kuczynski served as Minister of Economy and Finance from July 2001 to July 2002,[26] and again from February 2004 to August 2005. In August 2005, he was appointed as prime minister, a position he held until the end of Toledo's presidential term in 2006.[27][28]

In 2007, Manuel Dammert, a sociologist and politician, alleged that Kuczynski was involved in facilitating the activities, in various projects in Peru, of a financial entity known as First Capital Partners, in particular in relation to the Olmos diversion project, the Jorge Chávez International Airport, the Transportadora de Gas, and the Conrisa consortium. Former partners of Kuczynski in the Latin American Enterprise Fund had reportedly inaccurately listed Kuczynski as a founding partner of First Capital but corrected the error shortly afterwards. In consequence, Kuczynski sued Dammert for defamation and falsification of documents. Kuczynski prevailed at the first and second instance, but, on appeal, Peru's Supreme Court upheld Dammert's right to ask questions on matters of public interest, without ruling on the merits of Dammert's claims. These claims have been denied extensively by Kuczynski.[29]

After working with the Toledo administration, Kuczynski founded Agua Limpia, a Peruvian non-governmental organization that provides drinking water systems to communities in Peru.[30] Agua Limpia is supported by the Inter-American Development Bank, Scotia Bank of Canada and others.[31]

He ran unsuccessfully for president in 2011, but later went on to win the 2016 Peruvian general election against Keiko Fujimori, becoming the 66th President of Peru until March 2018.

Central Reserve Bank of Peru

editKuczynski returned to Peru in 1966 to support the government of Fernando Belaúnde Terry, as an economic adviser. He was appointed manager of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru. After the coup d'état against President Belaúnde on 3 October 1968, BCR managers Carlos Rodríguez Pastor Mendoza, Richard Webb Duarte and Pedro Pablo Kuczynski were accused of granting foreign currency certificates to the International Petroleum Company, allowing this company to remit $115 million of current profits to Standard Oil, its parent company in the United States. Due to this Kuczynski was forced to take refuge in the United States. After a judicial process that lasted eight years, the Supreme Court of Justice of Peru acquitted Kuczynski, and other BCR officials, of all charges.

Minister of Energy and Mines

editIn 1980, Kuczynski returned to Peru and collaborated in the election campaign of Belaúnde Terry, who was elected at his second and last non-consecutive term, and appointed Kuczynski as the Minister of Energy and Mines. As Minister, he promoted Law No. 23231, which promoted energy and oil exploitation; However, the so-called Kuczynski Law was not exempt from controversy because of the tax exemptions granted to foreign oil companies. In December 1985 it was repealed.

Minister of Economy and Finance

editDuring the presidential campaign of Alejandro Toledo, Kuczynski worked as the head of government planning team. He was later appointed as the Minister of Economy and Finance. As such, he made numerous agreements with the International Monetary Fund to help fulfill the goals in the neoliberal economic policies outlined by Peru. However, he was criticized on countless occasions by Alan García, the main leader of opposition to the government.

Prime minister

editAfter the increase in social protests in Arequipa due to the privatization of electric companies, he resigned on 11 July 2002. He returned to office on 16 February 2004, and was appointed as the Prime Minister of Peru on 16 August 2005, following the resignation of Carlos Ferrero Costa.

In a cabinet reshuffle, Kuczynski appointed Óscar Maúrtua as the Minister of Foreign Relations in replacement of Fernando Olivera, and Fernando Zavala as the Minister of Economy and Finance, his previous post. His premiership lasted through the end of Toledo's presidency in July 2006.

2011 presidential election

editOn 1 December 2010, Kuczynski announced that he would stand as a candidate for President of Peru in the upcoming elections.[32]

Kuczynski ran for President of Peru in the general election, though he did not pass into the run-off as head of the Alliance for the Great Change (Alliance for the Great Change), formed by the Christian People's Party, the Alliance for Progress, the Peruvian Humanist Party and National Restoration.[19] He took third place in the vote, his opponents Ollanta Humala and Keiko Fujimori went to the second round of elections on 5 June 2011, in which Humala was elected president of the country.

2016 presidential campaign

editIn 2015, he announced that he would run for president again, but with a political party that he had built himself (Peruvians for Change, Peruanos Por el Kambio, PPK).[33]

Kuczynski won 21% of the popular vote in Peru's general elections on April 10, 2016, to qualify for a runoff vote against Keiko Fujimori,[34] in which he narrowly triumphed with 50.12% of the vote to Fujimori's 49.88%,[6] a margin of just thirty-nine thousand votes out of nearly eighteen million cast. Barely a week before the second round of voting, while trailing Keiko, Kuczynski received an important endorsement from third-place finisher Verónika Mendoza (18.82%), Peru's leading left-wing candidate, in an effort to defeat Fujimori.[33]

Keiko's party, Fuerza Popular, had an absolute majority in Congress with 73 of the 130 seats; PPK trailed with 18.[33]

Presidency (2016–2018)

editKuczynski was sworn in as president on 28 July 2016.[7][8] At age 77, he was the oldest President to take office.[35]

As part of the recent push in Peru to recognize and integrate indigenous peoples into national life, Kuczynski's government supported the use of indigenous languages in Peru, with the state-run TV station starting to broadcast in December 2016 a daily news program in Quechua and in April 2017 one in Aymara. The President's state-of-the-union address was simultaneously translated into Quechua in July 2017.[36]

Almost immediately after winning the election, Kuczynski, despite previous public statements in support of social conservatism, appointed nearly all his ministers from the left (including many of Toledo's ex-ministers), and his government quickly became known for its promotion of feminism, abortion rights, and LGBT rights. This did not please the conservatives who had previously supported him, which led to the censure of two of his education ministers by the opposition-controlled congress, and a no-confidence vote for his entire cabinet in 2017.

Foreign policies

editKuczynski opposed the government of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, and welcomed Venezuelan expatriates. Nearly 200,000 Venezuelans settled in Peru, others moved to Peru, then later to Chile or Argentina. Kuczynski was one of the first leaders of the Latin American faction that asked for the democratization of Venezuela.[37] Peru revoked Venezuela's invitation to the 8th Summit of the Americas because of Maduro's plan to hold an early presidential election, as the major opposing parties were banned from it.[38]

Controversies

editFirst impeachment

editOn 15 December 2017, the Congress of the Republic initiated impeachment proceedings against Kuczynski, with the congressional opposition stating that he had lost the ″moral capacity″ to lead the country after he admitted receiving advisory fees from scandal-hit Brazilian construction company Odebrecht while he was Peru's Minister of Economy and Finance between 2004 and 2005.[39] Kuczynski had previously denied receiving any payments from Odebrecht, but later confessed that his company, Westfield Capital Ltd, had been receiving money from Odebrecht for advisory services, while still denying that irregularities existed in the payments.[40]

Pardon of Alberto Fujimori

editOn 24 December 2017, three days after surviving the impeachment vote, Kuczynski pardoned former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori.[41]

Second impeachment, Kenjivideos and resignation

editAfter further scandals broke out surrounding Kuczynski, a second impeachment vote was to be held on 22 March 2018. Two days before the vote, Kuczynski stated that he would not resign and decided to face the impeachment process for a second time. The next day on 21 March 2018, a video was released of Kuczynski allies, including his lawyer and Kenji Fujimori, attempting to buy a vote against impeachment from one official.[42]

Following the release of the video, Kuczynski presented himself before congress and officially submitted his resignation to the Congress of the Republic.[11][12] Kuczynski's first vice president, Martín Vizcarra, was later named President of Peru on 23 March 2018.

Resignation

editKuczynski announced his resignation from the presidency on 21 March 2018.[43]

I think what’s best for the country is for me to resign to the Presidency of the Republic. I don’t want to be an obstacle for the nation’s search for a path to unity and harmony that it very needs and that was refused to me. I don’t want the motherland nor my family to continue suffering with the uncertainty of these recent times.(...) There will be a constitutionally ordered transition.[44]

This came in result of the dissemination of videos and audios, known as Kenjivideos, that evidenced collusion between the executive and the legislature in order to give privileges and illicit profits to MPs in order to knock down the second impeachment process against Kuczynski. The resignation was accepted on 23 March 2018 by the Peruvian Congress and First Vice President Martín Vizcarra took oath immediately before the Congress.

Other presidents of Peru who have resigned are Guillermo Billinghurst (forced resignation), Andrés Avelino Cáceres and Alberto Fujimori. The current Peruvian Constitution of 1993 establishes in its article 113 that the Presidency of the Republic is vacated by:[45]

- Death of the President of the Republic.

- His permanent moral or physical disability, declared by Congress.

- Acceptance of his resignation by Congress.

- Leaving the national territory without permission of the Congress or not returning to it within the established period.

- Dismissal, after having been sanctioned for any of the infractions mentioned in Article 117 of the Constitution.

Congressional vote

editThe Board of Spokesmen of the Congress agreed to accept the resignation.[46]

On 23 March the acceptance of the resignation Kuczynski was approved, and a presidential vacancy was declared with 105 votes in favor, 12 votes against and four abstentions.[47][48]

| Party blocs | In favor | Against | Abstained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Popular Force | 56 | 0 | 0 |

| Peruvians for Change | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| New Peru | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Broad Front | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Alliance for Progress | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Popular Action | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Aprista Parliamentary Cell | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Independent | 12 | 0 | 4 |

| TOTAL | 105 | 12 | 4 |

Post-presidency (2018–present)

editLava Jato Case

editOn 10 April 2019, he was arrested along with his secretary Gloria Kisic Wagner and his ex-driver José Luis Bernaola for an alleged crime of money laundering in the Odebrecht case.[49] In turn, he authorized the Prosecutor's Office to search for 48 hours the homes linked to their surroundings in search of documents related to that case.

On 19 April 2019, Judge Jorge Chávez placed Kuczynski in preventive detention for the period of 3 years. Kuczynski received the news at a clinic in Lima where he was hospitalized for a cardiac intervention derived from a hypertension crisis. For Gloria Kisic Wagner and José Luis Bernaola, the judge rejected preventive detention and ordered that both serve a restricted appearance.

On 2 May 2019, Kuczynski left the clinic where he was hospitalized and was transferred to his home where he is under house arrest.[50]

Pandora Papers

editIn the Pandora Papers leak of 3 October 2021, Kuczynski was named in the revealed documents.[51][52] The leak allegedly showed that when Kuczynski was Minister of the Economy in July 2004, he created Dorado Asset Management LTD with the help of OMC Group in the British Virgin Islands.[52] Kuczynski's attorney responded to the Pandora documents saying "Dorado was conceived exclusively as a legal mechanism for patrimonial protection; it was used only for two properties acquired with money of lawful origin".[52]

Family and personal life

editHis father, Maxime Hans Kuczynski, was born in Berlin,[18] then part of the German Empire. He was a bacteriologist who served in the German Army during World War I on the Balkan front. He was a renowned pathologist and tropical disease specialist, in particular expert on Verruga peruana or Carrion's disease. He trained at the Universities of Rostock and Berlin, where he was professor of pathology.[53] His father was an officer in the German Army on the Eastern and Turkish fronts in the First World War, and he traveled widely in Russia, China, West Africa, and Brazil. Maxime Hans Kuczynski left Germany in 1933 due to persecution of his Jewish roots, and he was invited to Peru in 1936 by President Óscar R. Benavides to set up the public health service in the interior of the country. Maxime Hans Kuczynski reformed the San Pablo leprosarium on the Amazon at the Brazilian frontier, set up a public health colony on the Perene river, and was later professor of tropical medicine at National University of San Marcos in Lima.[54][55]

Kuczynski has been married twice, first to Jane Dudley Casey, the daughter of Joseph E. Casey, a former member of the United States House of Representatives for the 3rd district of Massachusetts. Their children are businesswoman Carolina Madeleine Kuczynski, the New York Times journalist Alex Kuczynski,[26] and John-Michael Kuczynski. Kuczynski and Casey divorced in 1995.

Kuczynski's second wife is Nancy Lange, an American and the First Lady of Peru until Kuczynski's resignation in 2018.[56] The couple, who married in 1996, have one daughter, Suzanne Kuczynski Lange, a biology graduate.[56][57][58]

Kuczynski's younger brother, Miguel Jorge Kuczynski Godard, is a fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge. Kuczynski's brother-in-law Harold Varmus was a Nobel Laureate for Medicine for cancer research in 1989.[33]

Kuczynski is a first cousin of French film director Jean-Luc Godard by his mother, Madeleine Godard, who was the aunt of the film director.[33]

He held U.S. citizenship until November 2015; he renounced it to be able to run for Peru's presidency.[33]

Kuczynski is a polyglot. Aside from his native Spanish, Kuczynski also speaks English and French fluently, and is proficient in German.

Electoral history

edit| Election | Office | List | Votes | Result | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | P. | ||||||

| 2011 | President of Peru | Alliance for the Great Change | 2,711,450 | 18.52% | 3rd | Not elected | [59] | |

| 2016 | President of Peru | Peruvians for Change | 3,228,661 | 21.04% | 2nd | → Round 2 | [60] | |

| 2016 | 8,596,937 | 50.12% | 1st | Elected | [61] | |||

Ancestry

editThis section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (March 2020) |

| Ancestors of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

edit- ^ In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Kuczynski and the second or maternal family name is Godard.

- ^ In isolation, Godard is pronounced [ɡoˈðaɾð].

References

edit- ^ Kcomt, Ricardo Monzón (21 March 2018). "Perú Crisis presidencial : PPK entre la renuncia y la vacancia [Análisis]". Peru21 (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Aprueban 36 meses de prisión preventiva para Pedro Pablo Kuczynski". CNN (in European Spanish). 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Mitos y verdades sobre PPK". Ppk.pe. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ "Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros". Pcm.gob.pe. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ "Elecciones Presidenciales, Congresales y de Parlamento Andino Peru 2011". Elecciones2011.onpe.gob.pe. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ a b LR, Redacción (6 June 2016). "Resultados ONPE: tendencia que favorece a PPK no se revertirá - LaRepublica.pe". Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Peru's New President Sworn in Surrounded by Ivy League Aides - ABC News". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Peru's New President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski Sworn in". BBC News. 28 July 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Collyns, Dan (15 December 2017). "Peruvian officials begin impeachment process against president Kuczynski". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ "PPK no fue vacado por el Congreso de la República" [PPK was not vacated by the Congress of the Republic]. El Comercio (in Spanish). 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b "PPK renunció a la presidencia del Perú tras 'keikovideos' | LaRepublica.pe". La República (in Spanish). 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.(Spanish)

- ^ a b "PPK renunció a la presidencia del Perú". Gestión (in Spanish). 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.(Spanish)

- ^ "Peru ex-president Kuczynski ordered into pre-trial house arrest". Reuters. 28 April 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Bartholomew Dean 2004 “El Dr. Maxime Kuczynski-Godard y la medicina social en la Amazonía peruana” Introduction in La Vida en la Amazonía Peruana: Observaciones de un medico. by Maxime Kuczynski-Godard. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Serie Clásicos Sanmarquinos; Compilation and introductory essay of second edition, originally published in 1944; digital copy here)

- ^ Carlos E. Cué; Jacqueline Fowks (11 April 2016). "Kuczynski, una vida entre el dinero y la política". El País. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Knipper, Michael (2009). "Antropología y 'crisis de la medicina': el patólogo M. Kuczynski-Godard (1890-1967) y las poblaciones nativas en Asia Central y Perú" [Anthropology and 'crisis in medicine': The pathologist M. Kuczynski-Godard (1890-1967) and the indigenous peoples of Central Asia and Peru]. Dynamis (in Spanish). 29: 97–121. doi:10.4321/S0211-95362009000100005. PMID 19852393.

- ^ "A Surprising Coalition Brings A New Leader To Peru". The New Yorker. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ a b Walk, Joseph (21 November 2014). Kurzbiographien zur Geschichte der Juden: 1918–1945 (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 208. ISBN 9783111580876.

- ^ a b "Profile of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski". Peru Reports. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "Individual Staff Members -- Kuczynski, Pedro-Pablo - World Bank Group Archives Holdings". archivesholdings.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Pérou: les grandes dates de Pedro Pablo Kuczynski". www.justiceinfo.net (in French). 21 March 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Kuczynski, Pedro-Pablo (February 1981). "The Peruvian External Debt: Problem and Prospect". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 23 (1): 3–28. doi:10.2307/165541. JSTOR 165541.

- ^ American Chamber of Commerce, Chile (13 April 2017). "Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, Curriculum Vitae" (PDF).

- ^ "PPK a Keiko Fujimori: 'Me fui del Perú por las amenazas de Sendero Luminoso'". Peru21.pe. 12 May 2016. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ "Las donaciones a los Bush". Diario16. Archived from the original on 25 March 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ a b "WEDDINGS/CELEBRATIONS; Alex Kuczynski, Charles Stevenson Jr". New York Times. 1 December 2002. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Zarate, Andrea (21 December 2017). "Bid to Oust Peru's President Falls Short in Congress". The New York Times.

- ^ "Perú: Alejandro Toledo seguirá detenido en EE.UU. hasta que se determine si será extraditado". France 24. 19 July 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Durand, Francisco (2018). Odebrecht, la empresa que capturaba gobiernos. Lima, Peru: Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru. p. 37. ISBN 978-612-317-425-5.

- ^ Sholtz, Laura (16 November 2016). "Dead Frogs and Oil Spills: Reconciling Kuczynski's Promise of Clean Water with Peru's Recurring Industrial Pollution Incidents". Council on Hemispheric Affairs / MIL OSI. Retrieved 2 August 2019 – via LiveNews.co.nz.

- ^ "Agua Limpia". Agualimpia.org. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Kuczynski será candidato a la Presidencia y el lunes presentará a sus aliados". Elcomercio.pe. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Anderson, Jon Lee (10 June 2016). "A Surprising Coalition Brings A New Leader To Peru". The New Yorker. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "2016 presidential elections". Peru Reports. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Briceno, Franklin; Goodman, Joshua (12 April 2016). "Fujimori's accidental rival embraces 'gringo' label in Peru". Associated Press. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "Peru's indigenous-language push". The Economist. Lima, Peru. 26 August 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Daniel Lozano (22 March 2018). "Un golpe para los venezolanos en su "tierra prometida"" [A harsh blow for the Venezuelans in their "promised land"] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Summit host yanks Venezuela's invitation over early election". WJHL. 13 February 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Peru's leader resists pressure to resign". Bbc.com. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Peru's leader faces impeachment". Bbc.com. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "UPDATE 6-Peru president pardons ex-leader Fujimori; foes take to streets". Msn.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Pressure builds on Peru president to quit over secret videos". Fox News. Associated Press. 21 March 2018.

- ^ Taj, Mitra; Aquino, Marco (21 March 2018). "Peru prosecutors seek to bar toppled president from leaving country: source". Reuters. Lima. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "PPK: Las frases que dejó su último mensaje presidencial" (in Spanish). Gestión. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Political constitution of the Peru" (in Spanish). onpe.gob.pe. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "PPK: Junta de Portavoces acordó aceptar su renuncia". El Comercio (in Spanish). 21 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Renuncia de PPK: los votos en contra y las abstenciones". El Comercio (in Spanish). 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Congreso acepta renuncia de Kuczynski a la Presidencia" (in Spanish). andina.pe. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Fowks, Jacqueline (25 March 2018). "La justicia peruana registra dos casas del expresidente Kuczynski y le prohíbe la salida del país". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ de 2019, 3 de Mayo (3 May 2019). "Pedro Pablo Kuczynski abandonó la clínica donde estaba internado y cumplirá arresto domiciliario en Lima". infobae (in European Spanish). Retrieved 12 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Lafuente, Javier; Martínez Ahrens, Jan (3 October 2021). "Pandora Papers in Latin America: Three active heads of state and 11 former presidents operated in tax havens". El País. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "Pandora Papers | Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, Sebastián Piñera y otros líderes latinoamericanos mencionados en investigación del ICIJ | PPK | MUNDO". El Comercio (in Spanish). 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Peru presidential contender is son of Polish Jews who fled Nazis". The Times of Israel. 6 April 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Bartholomew Dean 2004 “El Dr. Máxime Kuczynski-Godard y la medicina social en la Amazonía peruana” Introduction in La Vida en la Amazonía Peruana: Observaciones de un medico. by Máxime Kuczynski-Godard. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Serie Clásicos Sanmarquinos) (Compilation and introductory essay of second edition, originally published in 1944)

- ^ "La vida en la Amazonía peruana: Observaciones de un médico". sisbib.unmsm.edu.pe. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Conoce a Nancy Ann Lange, nueva primera dama de Peru". El Universal (Mexico City). 28 July 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "Commencement Exercises 2020, Princeton University". Princeton University. 31 May 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Presidente do Peru e a luta para manter seu mandato". Agence France-Presse. Universo Online. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ ""ELECCIONES GENERALES 2011 - PRESIDENCIAL"".

- ^ ""ELECCIONES GENERALES 2016 - PRESIDENCIAL"".

- ^ ""SEGUNDA VUELTA DE ELECCIÓN PRESIDENCIAL 2016 - PRESIDENCIAL"".

External links

edit- Official website (in Spanish)

- Pedro Pablo Kuczynski profile - El Mundo newspaper (in Spanish)

- PPK on Twitter

- Newsweek interview with Kuczynski

- Biography by CIDOB (in Spanish)