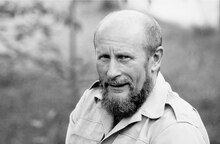

Pavel Nešleha (19 February 1937 – 13 September 2003) was a Czech painter, draughtsman, printmaker, photographer and creator of light objects. He received a number of important awards for his graphic and drawing work. He has exhibited individually since 1967 and participated in collective exhibitions since 1965. After the Soviet occupation in August 1968 and during the subsequent normalization, he was not allowed to exhibit freely. During the communist regime he was a member of the informal groups "Somráci (Vagabonds)" and "Zaostalí (the Backwards)". After 1990 he was a professor of painting at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague.

Pavel Nešleha | |

|---|---|

Pavel Nešleha, 1937–2003 | |

| Born | Pavel Nešleha 19 February 1937 Prague, Czechoslovakia |

| Died | 13 September 2003 (aged 66) Prague, Czech Republic |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Education | Alois Fišárek, Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, graphic art, photography |

| Spouse | Mahulena Hromádkova |

Life

editHe was born in Prague,[1] where he also attended primary school. His interest in art was inspired by the painter Vladimír Šebík, a pupil of Martin Salcman, who led an art club at the school. He continued his studies at the Václav Hollar Art School (1952–1956), where he also met his future friends: Zdeněk Beran, Antonín Málek, Kateřina Černá, Petr Bareš and Václav Křížek. Professors Zdeněk Balaš and Karel Tondl, under whom he studied, encouraged their students to learn about Czech modern art.[2] During his studies he had an opportunity to get acquainted with the private collection of art historian Vincenc Kramář, visited the studio of Emil Filla and saw the works of the Osma art group in Brno private collections. At the end of his studies, he attended public lectures by Prof. Jaromír Pečírka on the trends of modern art.[1]

From 1956 to 1962 he studied in the studio of monumental and applied painting of prof. Alois Fišárek at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. A breakthrough experience for his generation was the exhibition Founders of Czech Modern Art, organized in 1957 by Jiří Padrta and Miroslav Lamač in Brno. It was here that he first saw the expressive raw works of the Czech pre-war avant-garde - Kubišta, Filla, Procházka and Gutfreund.[3] During his studies, he attended meetings of young, avant-garde-oriented dissatisfied artists held in Antonín Tomalík's studio in Prague. Here he met artists from the future Confrontation circle as well as generationally related art history students František Šmejkal and Zdenek Felix. Together with Tomalík, Málek, Sion, Beran, Putta, Barborka, Steklík and others, he belonged to an informal group formed in pubs that called themselves "Somráci" (Vagabonds). They were united by a sense of defiance against the lack of freedom of the 1950s, a consciousness of being excluded and by radical attitudes.[1]

At the end of the 1950s, he took part in a school trip to Leningrad and Moscow; in the deposits of the galleries there, he got to know the originals of the leading figures of the European avant-garde, including works by Picasso, Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, Malevich, Chagall and Kandinsky. At the turn of 1959–1960, he attended lectures on modern and contemporary music organized by Dr. Josef Löwenbach for a circle of young artists and musicians. He maintained a friendship with Pavel Teimer, a student of typography in the studio of František Muzika at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, and with his peers from the circle of Prague studio Confrontations (1960). In 1960 he met Vladimír Boudník, whose unique graphic art inspired many followers. Nešleha's abstract composition for the space of the Music Theatre in Hradec Králové, which he submitted as his diploma thesis, was rejected for ideological reasons and destroyed on the spot; he completed his studies in 1962 with a set of expressive paintings from his junior year, for which he won the school's prize.[4]

He served his compulsory military service from 1962 to 1964 in Kolín, where he became acquainted with the work of Zdenek Rykr at the local museum.[2] In 1965, he participated in the first official exhibition Confrontation III at the Aleš Hall and other collective exhibitions (Gallery Fronta, 10 graphic artists in Ústí nad Orlicí). At the Book Graphics Fair in Leipzig (1965), together with Pavel Teimer, he received an honourable mention for a typographic set and for a set of structural prints for selected texts of Shakespeare's Hamlet. In 1967 he held his first solo exhibition at the Gallery of Youth in Prague's Mánes. He became acquainted with Jindřich Chalupecký and participated in his activities at the Václav Špála Gallery in Prague, as well as in subsequent private meetings held in private studios; he learned photography. At the beginning of 1968, he received a three-month scholarship from the French government and left for Paris in April 1968. His knowledge of the local art scene and the creative freedom there had a lasting influence on him. Shortly after the August occupation, he married Mahulena Hromádková, a student of art history, and took a study trip with her to Germany, Sweden, Holland and Belgium. At that time he also completed the construction of an attic studio in Vinohrady, which he used also as an apartment until 1986.

Beginning in 1970 and during normalization, with the help of friends and despite the bans, he participated in international exhibitions devoted to graphic art and drawing, where he won a number of important awards. He has participated in the prestigious exhibitions Biennale Internationale de l'estampe, Paris; Cien Grabados y Cien Fotografias, Universidad Nacional Autonóma de Mexico, Mexico City; 3. Internazionale der Zeichnung, Darmstadt; 9. International Graphic Art Exhibition, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana or Biennale of Drawing in New York, held in 1977. His success at the Darmstadt Triennial of Drawing in 1970 brought him an offer of a teaching position in drawing at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kassel, but despite numerous urgings from the German side, the Ministry of Culture of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic did not allow him to apply. In 1971, he won a gold medal at the Trieste Biennial of Graphic Arts (Premio Césare Sofianopulo) and in 1975 a silver medal for graphic art at the MIR 75 international exhibition, which was organized for the 30th anniversary of the United Nations.[5]

At the beginning of the 1970s he was approached by the architect Miroslav Hrubý to design lighting for the vaulted Baroque space of the castle.[6] Since 1971 he has been devoted to spatial lighting objects, for which he received a patent.[7] He used them for the set of the Liberec theatre Ypsilonka for the performance Depeše psané na kolečkách. He exhibited some of the objects of the Light Twelve-hedron (1972–1973) and large-scale drawings from the Chairs series (1972) at a solo exhibition at the Baukunst Gallery in Cologne in 1974, but was not allowed to travel there. He made several light objects in the Iranian pavilion at the World Oceanographic Expo in Okinawa, Japan in 1974, from where he made a short study tour of Japan (Tokyo, Nara, Kyoto). He subsequently used the architectural project of a luminous Twelve-hedron with the symbolism of hand reliefs partly for an installation in the Marble Palace in Tehran (1976). During his stay in Iran he had the opportunity to visit other cities - Persepolis, Ifsahan, Meshed, Shiraz and some smaller towns in the desert.[8] The monumental pathos of the Iranian landscape made Nešleha to return to painting and colour.[9]

In 1977 the Nešleha family had a daughter, Johanna.[10] In the late 1970s he returned to painting. In 1979, he was in the Premio internazionale exhibition in Biella, Italy, in a selection of 20 world graphic artists. In the same year, Jan Kříž managed to prepare an exhibition of 10 x 5 drawings in Valašské Meziříčí, where, in addition to Nešleha, Beran, Lamr, Mergl, Načeradský, Nepraš, Sion, Sopko, Steklík and Šimotová exhibited.[8] Galerie Sonnenring in Münster (1980) organized a small retrospective for him in cooperation with art historian Jan Kříž. He had further chamber exhibitions in small unofficial exhibition spaces in Brno ("Club of Education", "Veterinary Institute"). Together with Zdeněk Beran, he became close friends with Bedřich Dlouhý and Hugo Demartini. At the beginning of September 1981, he participated in a private exhibition of eighteen selected artists and theoreticians of modern art at Bedřich Dlouhý's estate in Netvořice, organized on the initiative of Jindřich Chalupecký. The participants were followed and identified by the police. He took part in an unofficial exhibition in the Gamekeeper's lodge at the Star Game Preserve, prepared by Marie Klimešová in 1982. In 1983 he had solo exhibitions of paintings and drawings at the Regional Museum in Kolín (Jan Kříž) and then at the Old Town Hall in Prague (Hana Rousová)[11] and was represented at the prestigious show Dessins tchèques du 20e siècle at the Centre Georges Pompidou. On that occasion, he was able to travel for the first time in a long time and visited Paris.

In 1984-1986 he worked on environments with painting and photography. In 1986, Jiří Valoch organized Nešleha's retrospective in Brno at the House of the Lords of Kunštát. In a joint exhibition with Hugo Demartini in Zižkov Atrium Gallery he exhibited some door objects from the series Illusions in Privacy. In the summer of 1986 the Nešleha family moved to Braník.[12] Since 1987 Pavel Nešleha was a member of the association New Group.[13]

During the preparation of a joint installation at the unofficial intergenerational exhibition Forum '88 in the Holešovice marketplace in Prague, a group with the ironic name Zaostalí (The Backwards) emerged from a friendly and opinionated group (Dlouhý, Demartini, Beran, Nešleha). Subsequently, they invited the composer Jan Klusák (as a theoretician) and the architect Karel Kouba for an upcoming unofficial multimedia exhibition, which was to take place in People's House in Vysočany at the end of 1989. After the collapse of the communist regime, it was never held and The Backwards were given the opportunity to exhibit in the Nová síň Gallery and in the Mánes Building of the Society of Visual Artists.[14] In autumn 1989 Pavel Nešleha made a study trip to Italy (Venice, Florence, Rome), where he became more familiar with Caravaggio's and Tintoretto's paintings.[15]

In 1990, Nešleha received a creative grant from The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and from the same year until 2002 he was the head of the painting studio at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. In 1991 he was appointed professor. He prepared a number of study trips abroad for his students (Italy, Germany, Spain, France).[16] Since 1991 he has participated in Czechoslovak art shows abroad (Bonn, Osnabrück, Bochum, Vienna, Paris, Sarajevo, Tuzla). In 1992 he took part in the international creative symposium Baroque and Today in Litoměřice. On the occasion of the AICA Congress in Prague, The Backwards installed their individual artefacts, created at the end of the communist regime, in Mánes as a joint work under the title "Pile".[15]

In 1994, the Czech Museum of Fine Arts prepared a large travelling retrospective for Nešleha (Czech Museum of Fine Arts Prague, Gallery of Art Karlovy Vary - Ostrov nad Ohří, Gallery of Modern Art in Hradec Králové).[16] In 1995, he became a member of the Mánes Union of Fine Arts. Shortly after his solo exhibition at Mánes in 1997, where he presented his large-scale digital prints Via canis, he underwent a serious operation and chemotherapy. Between 1997 and 2003 he alternated between printmaking, pastels and photographic work. In 2001, he travelled to the south of France and accepted the position of Vice-Rector of Studies at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. In September 2003, shortly before the opening of his personal exhibition of pastels from the series Records of Light at the Gallery of Modern Art in Roudnice nad Labem, he unexpectedly succumbed to an insidious illness.[17] The last exhibition of the group The Backwards (Zaostalí) took place in 2007 in the gallery of the Municipal Library in Prague.[18]

Artwork

editPavel Nešleha belonged to the generation of Czech non-conformist art of the 1960s and to the circle of artists close to Jindřich Chalupecký. He was a Romantic and Expressionist artist with a strong pictorial vision. More important to him than the artistic processes themselves was the inner content, transformed into the existential pathos of his works.[19] He was gifted with a sense of the right choice of artistic means to communicate his ideas and intentions. In addition to paintings, prints, drawings and pastels, his thematically rich oeuvre also includes spatial objects, collages, light installations, photographs and large-scale digital prints.

From the expressive paintings of the late 1950s, inspired by Kubišta, in the early 1960s his painting gradually simplified into a flat sign expressing the existential situations of human life under the influence of Georges Rouault (Figure, 1959, 1960). The inspiration came also from biblical motifs and literary themes of Edgar Allan Poe or Shakespeare's Hamlet. At the turn of 1959/1960, he became familiar with the works of Antoni Tàpies, Jean Dubuffet, Alberto Burri and Vladimír Boudník and, like most of his generational contemporaries, he devoted himself to structural abstraction in graphic art and painting (Untitled, mixed media, 1959). He used a paper base on which he glued additional layers of paper or fine synthetic fabric and after transferring it to canvas, finished the structure with oil paint (Untitled I and II, 1960).[20] Pertinax plates served as printing material and Nešleha created structural prints by burning their surface (Structural Graphics, 1962).[21] His diploma thesis, designed for the space of the Theatre of Music in Hradec Králové in 1961, was also abstract in concept.[22] During his military service he printed some structural prints from the cycles Studies for Hamlet (1962–1964) and Fragments (1962–1963) in a manual laundry dryer.[23]

-

Church in Kyje (1958)

-

No title, structural print (1962)

From the mid-1960s onwards, hints of figuration were reasserted in his work.[24] Photographic details of autotype plates, which Nešleha deformed by burning and incorporated into graphic matrices, played a part in this. Attracted by the images of the obtained plates, he taught himself to take photographs. Pavel Nešleha's immediate reaction to the sudden end of hope after the Soviet occupation in August 1968 was a series of wild drawings and paintings with fragments of deformed human faces and limbs, which he created as personal art therapy (paintings Head; Roar; Dinner all from 1969).[25]

During 1969-1970 he took detailed photographs of hand gestures. The photographic experience increased the artist's attachment to the reality he saw and in the late 1960s gave rise to large-scale drawings with exaggerated detail accentuating the senses of the human body (Senses I - III 1969; Palm, 1969–1970). The interest in the precisely seen object also influenced the methods of artistic communication. In 1969, he began to etch his own photographic images into graphic matrices, which he combined with the drypoint technique. Unexpectedly, with his graphic sheets (the series History of the Human Hand, 1969–1972;[26] The Great Demolition, 1970, etc.), he entered the artistic movement of photorealism (hyperrealism), which was then taking shape in the USA. The History of the Human Hand series began as a reflection on the early imprints of human existence in prehistoric caves, but gradually became a metaphor for human suffering, misery and aggression. Playing with photographic and later television images brought new themes and transformation to the grotesque presentation of human downfall in response to the trauma of occupation.[25][19]

-

Head IV (1969)

-

Palm (1969–70)

-

History of the Human Hand I (1970)

-

History of the Human Hand II (1970)

His light objects, which he had been creating since 1971, resulted in the architectural project of the Light Twelve-hedron (1972–1973). Its interior space with a light projection of organic forms of the human body, which contrasted with the geometry of the architecture, was intended to provide the viewer with an opportunity for meditation.[27] He exhibited some of the objects of the "twelve-hedron" at a solo exhibition at the Galerie Baukunst in Cologne in 1974, but was not allowed to attend the opening. He made several light objects for the Iranian pavilion at the World Oceanographic Expo[28] in Okinawa, Japan in 1974. Based on architectural design of the luminous twelve-hedron was the design of the oval space, consisting of walls of artificial stone with hand-shaped reliefs and combined with mirrors, inserted into the large hall of the Marble Palace in Tehran (1976).[8] A number of Czech artists then participated in the monumental commission, organized by Art Center employee J. Frič.[29]

The relationship to the real motive has no longer deserted his mind. The veristically processed element was at first critically permeated by the ironic grotesqueness and absurdity with which Nešleha reacted to the manipulation and unfreedom of the incipient normalisation, perceived as a "horrible nightmare".[9] In 1972, he created a series of large-scale drawings on the theme of human decadence (Chairs), later TV Story (1975), the prints Sour Apple (1977), etc. Subsequently, the real object led him to reveal its hidden essence. The peculiar, almost surreal subject matter resulted in the late 1970s in a meditative profundity and in a symbolic appreciation of the phenomenon of light (drawing series Time of Open Doors, 1977; paintings Window, 1978; Melioration, 1981, etc.). The use of the effects of light also reflected his former experience with light objects and reliefs, which he dealt with between 1971 and 1975. In 1981-1982 he was involved in the design of the corridor of the Czechoslovak Memorial in Auschwitz, for which he created nineteen large-scale pencil drawings. In 1982 he photographed details of natural structures and by 1983 he was producing a large series of drawings entitled Studies of Objecthood.[11]

-

Luminous object (1973)

-

From the cycle Chair (1972)

-

Time of Open Doors VI, (1978)

-

Time of Open Doors VII (1978)

-

Study of fire (1988)

The attachment to nature, modified by the legacy of the Romantics and the symbolic concept of light, became the starting point for the artist's further work in the 1980s. He used classical painting to portray his pictorial visions, which allowed him to include realistically conceived enlarged detail in an imaginary free space and thus make it visible (Revolt, 1981; An Attempt of Journey after K. H. Mácha, 1982; Farewell to C. D. Friedrich, 1982; The Long Journey, 1983; Traces, 1983, etc.; drawings Study of Objecthood, 1982–1984, Draught, 1984, etc.). It was a fundamental discovery that led him to a deeper perception of reality and to an effort to grasp its hidden essence. Nešleha's imagination and detailed drawings gave everyday and inconspicuous motifs the dimension of general symbols that were a metaphor for Czechoslovak society at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s.[30]

-

Uprooting (1981)

-

An Attempt of Journey after K. H. Mácha (1982)

-

Farewell to C. D. Friedrich (1982)

-

Path (1983)

Frequent trips to the countryside associated with photography, the extremes of rugged mountain landscapes, or historic works that create a "memory of place" have been his frequent inspirations. His imagination was enriched by the roots of the Šumava primeval forests, the erosion of sandstone rocks, the statues of Matthias Bernard Braun in Kuks, or the heads and masks of Václav Levý near Liběchov.[31] He reflected on Romanticism and its attempt to capture the human condition in relation to nature and its unbridled forces. In the mid-1980s, the original idea led to the creation of a monumental environment consisting of four monochrome triptychs in the basic scale of Goethe's system, forming an enclosed space 7 m in diameter around the viewer (Elements, 1983–1984).[27] He was attracted to the idea of depicting the elements as rolling masses as well as the destructive power of fire, the chilling depth of space and the eruptive force of the Earth.[32] During the 1980s, he began to incorporate the paradox of combining illusory painting with real elements into the conception of his works; he created large-scale objects of doors (the series Illusion in Privacy, 1985–1988),[24] assemblages and pictorial installations (Neither on Earth nor in Heaven, 1989). In doing so, he attempted to escalate the illusion in non-attachment to a given object or action embedded in a real object (Flood, 1985).[31]

-

Flood, from the series Illusions in Private (1985)

-

Time has passed, from the series Illusions in Private (1986)

-

Neither on earth nor in heaven (1989)

The theme of the elements demonstrating the potential of natural forces found a firm motivic basis in Nešleha's art. He worked on them in drawings (Study of Fire, 1988), paintings (Transformations I and II, 1990), photographs and large-scale digital prints (Elements, 1999; the cycles Braun Reflections and Ojbín from 2000, Natural Structures, 2001). In the 1990s, he devoted himself to mythical themes addressing the irreversibility of human destiny, as evidenced by his pastels and drawings (Icarus's Fall, 1991–1902; Oedipus, 1992–1993; the series Memoirs of the Earth, 1992; and the paintings Is There a Solitude of Space? (1992) and The Event (1988–1996). He conceived the series The Glitter and Misery of Apocalyptic Horses (1994) as an ambivalent narrative presented through two opposing fields of filmstrip, where clouds turn into images of stampeding horses; their demise follows, ending on the one hand with a horse's skull as a memento and on the other with a massive hoof crushing the old world in anticipation of a new reality. The series ends with a pastel with a mysterious Hebrew inscription.[30]

-

Study to Icarus's Fall (1991)

-

Oedipus III (1992)

-

Oedipus V (1993)

-

Mystery of the Signs (1993)

In 1997, he presented large-format photo-objects Via canis in Mánes Gallery - photographs of ordinary covers of public lighting poles, which have acquired a special individuality due to the effects of time and rust. They can be perceived as masks bearing a minimal likeness of a human face and evoking the association with a host of knights returning from a crusade. The installation, which could be understood as a spiritual journey, was complemented by a large-scale image of a human palm as protection and redeemed authority. The counterpart was Transformation of Imagery with the motif of hair as a symbol of power and spiritualized energy.[30]

-

From the cycle Via Canis (1997)

-

From the cycle Via Canis (1997) II

-

From the cycle Ojbín (2000)

-

Transformation of Imagery (1997)

Since the beginning of the new millennium, the symbolic concept of coloured and then white spiritual light began to re-enter the artist's imagination. The former attachment to visual reality gradually disappeared; it was absorbed by the abstract concept of signs and luminous visions realized in paintings and in the pastel technique (Square II, 2000; Initially Me Wants to Ascend, 1999–2000; series of pastels Records of Light 2002–2003). The triptych Initially Me Wants to Ascend was created during a symposium at the Plasy Monastery as a reflection of the Santini staircase. Nešleha's creative journey came to an unexpected end in September 2003 with his light visions Records of Light, which attempted to represent the light-coloured images he perceived while listening to music or working.[33]

-

Mathias's Mirror (1998–1999)

-

Square II (2000)

-

From the cysle Natural Structures I (2001)

-

Records of Light (2002–03)

-

Records of Light (2002–03)

Representation in collections

edit- Musée national d'art moderne – Centre Georges Pompidou

- Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris

- Museum of Drawing and Graphic Art, Washington

- Museum Bochum

- Sonnenring Galerie, Münster

- Baukunst Galerie, Cologne

- Museum Sztuki, Łódž

- Muzej suvremene umjetnosti, Beograd

- Moderna galerija Ljubljana

- Umjetnička galerija BiH, Sarajevo

- Czech Republic: National Gallery Prague, Moravian Gallery in Brno,[34] Aleš South Bohemian Gallery in Hluboká, Gallery of Art, Karlovy Vary, North Bohemian Gallery of Fine Arts in Litoměřice, West Bohemian Gallery in Plzeň, Klatovy / Klenová Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art in Roudnice nad Labem, Gallery of Modern Art in Hradec Králové, Gočár Gallery in Pardubice, Gallery of the Central Bohemian Region in Kutná Hora (GASK), Museum of Art, Olomouc, Regional Gallery in Liberec, Regional Gallery in Jihlava, Benedikt Rejt Gallery at Louny, Museum of Czech Literature in Prague, Terezín Memorial, Museum Kampa – Foundation of Jana and Meda Mládek, Prague, Zlatá husa Gallery, Prague, COLLETT Prague/Munich

Exhibitions (selection)

edit- 1967 Gallery of Young, Mánes, Prague

- 1974 Handzeichnungen und Druckgraphik, Baukunst, Cologne

- 1979 Minigalerie - Research institute of veterinary medicine, Brno

- 1980 Sonnenring Galerie, Münster

- 1983 Obrazy a kresby z let 1978-1983 / Paintings and drawings from 1978 to 1983, Regionální muzeum v Kolíně

- 1983 Kresby a obrazy z let 1976-1983 / Drawings and paintings from 1976-1983, Staroměstská radnice, Prague

- 1986 Obrazy, kresby, fotografie / Paintings, drawings, photographs, Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno

- 1992 Galerie Nová síň, Prague

- 1994-1995 Galerie moderního umění, Hradec Králové, České muzeum výtvarných umění, Prague, Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích

- 1997 Práce z poslední doby / Recent works, Mánes, Prague

- 2001 Sedimenty paměti / Sediments of memory (Česká kresba 14), Galerie umění Karlovy Vary

- 2001 Sedimenty paměti II. - Malby, kresby, fotografie / Sediments of memory II, Paintings, drawings, photographs, Galerie Klatovy / Klenová

- 2002 Sedimenty paměti III. - Přírodní elementy / Sediments of memory III - Natural elements, Pražákův palác, Brno

- 2003-2004 Záznamy světla / Records of light, Galerie moderního umění, Roudnice nad Labem, Letohrádek Hvězda, Prague

- 2008 Nejen o zemi. Z cyklů kreseb, fotografií a pastelů / Not just about the country. From cycles of drawings, photographs and pastels, Dům pánů z Kunštátu, Brno[35]

- 2012 Fotografická tvorba / Photographic work, Galerie města Pardubic (GAMPA)

- 2013 Sedimenty paměti IV / Sediments of memory IV, Wortnerův dům Alšovy jihočeské galerie, České Budějovice

- 2016 Via Canis, Museum Kampa - Nadace Jana a Medy Mládkových, Prague[36]

- 2020 Vidět jinak / To See Differently, Dům umění, Ostrava[37]

References

edit- ^ a b c Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 289

- ^ a b Sophistica Gallery: Pavel Nešleha

- ^ Pavel Nešleha, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, s. 46

- ^ Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 290

- ^ GVU Ostrava: Pavel Nešleha

- ^ Pavel Nešleha, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 136

- ^ Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, s. 293

- ^ a b c Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 294

- ^ a b Pavel Nešleha, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 156

- ^ Johanna Genest Neslehova, Professor, Mathematics and Statistics, McGill University, Montréal

- ^ a b Nešlehová M, in. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 295

- ^ Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 296

- ^ New Group: Summer 1991

- ^ cz/zaostali-forever-5076285 Zaostalí Forever, ČRo Mozaika, 2007

- ^ a b Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p 297

- ^ a b Nešlehová M, in. 298

- ^ Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, s. 301

- ^ J. Machalický, The Municipal Library, the exhibition space of the Prague City Gallery, hosts an exhibition of a peculiar group, Lidovky, 2007

- ^ a b Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 32

- ^ Primus Z, 2003, pp. 78-81

- ^ Pavel Nešleha, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 56

- ^ P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, pp. 78-79

- ^ Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, s. 291

- ^ a b Pavel Nešleha - Possibilities of Depiction, Gallery of the University of Applied Arts, 2014

- ^ a b Pavel Nešleha, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, s. 90

- ^ Nešlehová M, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 292

- ^ a b Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 34

- ^ International Ocean Exposition, Okinawa 1975

- ^ Kramerová D, (2013, pp. 341-355)

- ^ a b c Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 33

- ^ a b Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 35

- ^ Pavel Nešleha, in: P. Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 186

- ^ Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 2004, p. 36

- ^ Pavel Nešleha, MG Brno

- ^ Dům Pánů z Kunštátu vystavuje fotografie symbolisty Nešlehy, iDNES 2008

- ^ Pavel Nešleha: Via Canis, Museum Kampa, 2016

- ^ Pavel Nešleha: Vidět jinak, GVU Ostrava 2020

Sources

editMonographs

edit- Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha: Stopy síly (Fotografie z let 1971-2002 / Traces of Force (The photographs from 1971 to 2002), 108 s., Nakladatelství KANT (Karel Kerlický), Prague 2012, ISBN 978-80-7437-076-2

- Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha, 352 pp., Gallery, Prague 2004 ISBN 80-86010-72-4

Author's catalogues (selection)

edit- Mahulena Nešlehová: Pavel Nešleha: Vidět jinak / To See Differently, 31 p., Galerie výtvarného umění v Ostravě 2020, ISBN 978-80-87405-53-6

- Petr Wittlich a kol., Pavel Nešleha: Poutalo mě světlo... / Drawn to the Light..., 55 p., SGVU Litoměřice 2014, ISBN 978-80-87784-04-4

- Vlastimil Tetiva: Pavel Nešleha: Sedimenty paměti (IV) / Sediments of memory, 12 p., AJG Hluboká 2013, ISBN 978-80-87799-00-0

- Pavel Nešleha - Nejen o zemi (Z cyklů kreseb, fotografií a pastelů), 43 p., Dům umění města Brna 2008, ISBN 80-902542-6-8

- Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha - Záznamy světla / Records of Light, 20 p., Letohrádek Hvězda, Prague 2004, ISBN 80-85085-66-6

- Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha - Záznamy světla / Records of Light, 30 p., Galerie moderního umění, Roudnice nad Labem 2003, ISBN 80-85053-44-6

- Pavel Nešleha: Z fotografických cyklů / From the photographic cycles, Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění v Litoměřicích 2003, ISBN 80-85090-49-X

- Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha - Sedimenty paměti / Sediments of memory (Czech drawing 14), Galerie umění Karlovy Vary 2001. ISBN 80-85014-45-9

- Petr Wittlich: Pavel Nešleha - Práce z poslední doby / Recent works, Mánes, Prague 1997

- Jan Kříž: Pavel Nešleha, 90 p., České muzeum výtvarného umění, Prague 1994

- Petr Wittlich, Pavel Nešleha, Galerie Nová síň, Prague 1992

- Jiří Valoch: Pavel Nešleha: Obrazy / kresby / fotografie (Paintings / drawings / photographs), Dům umění města Brna 1986

- Jan Kříž, Pavel Nešleha: Obrazy a kresby z let 1978-1983 / Paintings and drawings from 1978 to 1983, Regionální muzeum v Kolíně 1983

- Jiří Valoch: Pavel Nešleha, 8 p., Minigalerie - Výzkumný ústav veterinárního lékařství, Brno 1979

- Jan Kříž: Pavel Nešleha, 28 p., Sonnenring Galerie, Münster 1978

- Pavel Nešleha: Handzeichnungen und Druckgraphik, 16 p., Cologne 1974

- Pavel Nešleha, cat. 4 p., SČVU Prague 1967

General publications (selection)

edit- Jiří Jůza, Stopy ohně / The traces of fire, 84 p., Dům umění, Ostrava 2009, ISBN 978-80-85091-92-2

- Petr Wittlich, Mahulena Nešlehová (eds.), Zaostalí FOREVER / The Backwards Forever, Gallery, Prague 2007 ISBN 978-80-86990-15-6

- Richard Drury a kol., Soustředěný pohled / Focused View (1960s Prints from the Collections of Czech Galleries Association Members), 179 p., Rada galerií České republiky RGČR, Prague 2007, ISBN 978-80-903422-2-4

- Vlastimil Tetiva, České umění XX. století: 1970-2007 / Czech Art of the 20th Century: 1970–2007, 326 p., AJG Hluboká 2007, ISBN 978-80-86952-42-0

- Mahulena Nešlehová, Poselství jiného výrazu (Pojetí informelu v českém umění 50. a první poloviny 60. let) / The Message of Another Expression (The Concept of Informel in Czech Art of the 1950s and the First Half of the 1960s), 286 p., Artefact, Prague 1997, ISBN 80-902160-0-5

- Jindřich Chalupecký: Nové umění v Čechách / New Art in Bohemia, H&H, Prague 1994, pp. 72–73. ISBN 80-85787-81-4

- Marie Klimešová, Ohniska znovuzrození: České umění 1956-1963 / Focal Points of Revival: Czech Art 1956–1963, 447 p., Městská knihovna Prague 1994, ISBN 80-7010-029-X

- Pavla Pečinková, Contemporary Czech Painting, 235 p., G+B Arts International Limited, East Roseville 1993, ISBN 976-8097-25-6

- Eva Petrová et al., Barok a dnešek / Baroque and Today, 136 p., Symposion Foundation 1992, ISBN 80-901195-8-1

- Karin Thomas: Tradition und Avantgarde in Prag, Du Mont, Cologne 1991, pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-3-7701-2842-6

- Jan Kříž, Zaostalí / The Backward, 48 p., Department of Education and Culture, Prague 9, 1990

- Šedá cihla 78/1985 / Grey brick 78/1985, 322 p., Jazzová sekce, Prague 1985

- Victoria Thorson: Great Drawings of All Time – The Twentieth Century, Shorewood Fine Art Books, New York 1979, ISBN 0-935986-00-6

Encyclopedias

edit- Rostislav Švácha a Marie Platovská (eds.), Dějiny českého výtvarného umění / History of Czech Art [VI/1,2] 1958/2000, Academia, Prague 2007, pp. 193, 604–606, 653–655, ISBN 80-200-1489-6

- Alena Malá (ed.), Slovník českých a slovenských výtvarných umělců 1950–2002 / Dictionary of Czech and Slovak Visual Artists 1950-2002 (IX. Ml – Nou), Výtvarné centrum Chagall, Ostrava 2002

- Milan Churáň (ed.), Kdo byl kdo v našich dějinách 20. století (II. díl N-Ž) / Who was who in our 20th century history (Part II N-Z), Libri, Prague 1999

- Anděla Horová (ed.), Nová encyklopedie českého výtvarného umění (NEČVU) / New Encyclopedia of Czech Fine Arts, Academia, Prague 1995, pp. 564–565, ISBN 80-200-1209-5