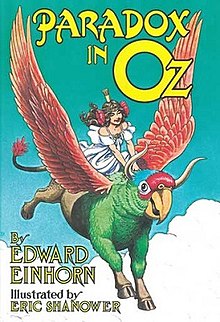

Paradox in Oz is a 1999 novel written by Edward Einhorn. The book is an entry in the series of books about the Land of Oz written by L. Frank Baum and a host of successors.

| |

| Author | Edward Einhorn |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Eric Shanower |

| Cover artist | Eric Shanower |

| Language | English |

| Series | The Oz Books |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Hungry Tiger Press |

Publication date | 1999 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 237 |

| ISBN | 1-929527-01-2 |

| OCLC | 44424711 |

| LC Class | PZ7.E34445 Par 1999 |

The book

editParadox in Oz was published by Hungry Tiger Press, with illustrations by Eric Shanower. It was playwright Einhorn's first novel and first Oz book. (His second in both categories, The Living House of Oz, would appear in 2005.) The publication of Paradox in Oz was timed to coincide with the centennial of the original Oz book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (as was also true of Gina Wickwar's The Hidden Prince of Oz and Dave Hardenbrook's The Unknown Witches of Oz). Einhorn's novel was warmly received and widely praised upon its initial publication,[1] as were Shanower's illustrations; a review in Asimov's Science Fiction called it a "gorgeous book."

Genre

editIn Paradox in Oz, Einhorn maintains a fidelity to the benign utopian fantasy of Baum's Oz novels, though he also acknowledges the darker revisionist vein explored in contemporary books like Geoff Ryman's Was and Gregory Maguire's Wicked trilogy. Einhorn constructs an alternate, dystopian version of Oz,[2] an Obsidian City in contrast to Baum's Emerald City.

Einhorn's book is also notable for its use of science fiction elements, principally time travel. There is a science fiction thread that winds through Baum's work,[3] manifested in non-Oz books like The Master Key but also in the Oz stories, with robots (Tik-Tok of Oz), domed cities (Glinda of Oz), and other features. Critics have remarked on the interest in and acceptance of technology that sets Baum's Oz apart from earlier fantasy domains.[4][5][6]

Synopsis

editAs the novel opens, inhabitants of Oz are suddenly noticing unusual signs of aging. Omby Amby finds a white hair in his luxurious green beard, and common citizens confront wrinkles and back problems. Ozma and her advisers realize that the magic anti-aging spell, which has prevailed in Oz throughout her reign, has now stopped working. In their attempt to figure out why, Ozma and Glinda consult the Great Book of Records, but find cryptic references to the "Man Who Lives Backwards." (This person is actually living in Glinda's palace at the moment; but since he lives backwards, he is a baby in the present time, and cannot explain himself to them.)

In trying to puzzle out the problem, Ozma and Glinda confront a Parrot-Ox — a large magic creature, half parrot and half ox. "Its front half was covered with red, blue, and green plumage, and out from among its feathers proudly emerged a bright yellow beak. Two large, orange wings rested against its body, which was a speckled brown, and it had a long black tail with a feathered end. It stood upon four hooved feet, and its dark eyes darted nervously around the room, dismayed at being discovered." They learn that these creatures, normally invisible, are amazingly common; they co-exist with us in our everyday lives. A Parrot-Ox is "capable of doing nothing at all, unless it is impossible."

This particular Parrot-Ox calls himself Tempus. To resolve the mystery of the aging of Oz, Ozma rides Tempus back in time, to meet her predecessor King Oz in the forest surrounding the Forbidden Fountain. She encounters a curious person called Dr. Majestico, and she accidentally changes the past so that Oz becomes an evil place, ruled by a tyrannical Wizard from an Obsidian City, a negative-image of her own Emerald City. She must deal with altered versions of her familiar friends: the beautiful Glinda is old and worn, while the Tin Woodman is a human and very malevolent headsman, Nick Chopper.

In her efforts to remedy the situation, Ozma takes more and more trips into the past; the woods around the Forbidden Fountain are soon filled with Ozmas from different times. Ozma must confront Tip, her own earlier male self, and take a journey to Absurd City to find the Man Who Lives Backwards; she must face mind-boggling confusions, and numerous Parrot-Oxes, before she can restore the familiar world she knows and loves.

Ozian allusions

editFans of Oz will find subtle allusions in Einhorn's text. In Chapter Six, for example, Tempus tells Ozma that he remembers things that "never happened," such as "when East used to be West and West used to be East...."[7] This is a reference to a major and well-known contradiction in the Oz literature. In the second chapter of the original Oz book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum specifically places the Munchkin Country in the eastern section of Oz;[8] Dorothy's house famously kills the Wicked Witch of the East when it lands on her there. Yet in later books, Tik-Tok of Oz and The Lost Princess of Oz, maps show the Munchkin Country in the west.

In Obsidian City, the alternative version of Omby Amby calls himself Wantowin Battles — a name introduced by Ruth Plumly Thompson in her Ozoplaning with the Wizard of Oz (1939).

When dealing with Dorothy, the Evil Version of the Wizard makes a reference to the 1939 movie version, by reversing part of the Wizard's dialog, describing himself, as "a very bad man, but I am a very good wizard," before performing a wicked spell on the girl.

The illustrations

editEric Shanower's black-and-white illustrations for Paradox in Oz are faithful to the richly romantic style that Shanower has developed for Oz illustration, from The Enchanted Apples of Oz (1986) on. Yet for pertinent incidents in Einhorn's text, Shanower expands his style to include elements of pop art and op art, and allusions to the work of M. C. Escher.[9]

References

edit- ^ Edward Einhorn, The Golem, Methuselah, and Shylock: Plays by Edward Einhorn, New York, Theater 61 Press, 2005; p. 3.

- ^ Richard Carl Truek, Oz in Perspective, Jefferson, NC, McFarland, 2007; pp. 103-4.

- ^ George E. Slusser and Eric S. Rabkin, eds., Intersections: Fantasy and Science Fiction, Carbondale, IL, Southern Illinois University Press, 1987.

- ^ Paul Nathanson, Over the Rainbow: The Wizard of Oz as a Secular Myth of America, Albany, NY, State University of New York Press Press, 1991.

- ^ Marius Bewley, Masks & Mirrors: Essays in Criticism, New York, Atheneum, 1970.

- ^ Suzanne Rahn, The Wizard of Oz: Shaping an Imaginary World, New York, Twayne, 1998.

- ^ Paradox in Oz, p. 67.

- ^ L. Frank Baum, The Annotated Wizard of Oz, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Michael Patrick Hearn; revised edition, New York, W. W. Norton, 2000; pp. 60-1, and illustration facing p. xlix.

- ^ Paradox in Oz, pp. 165, 173, 175.