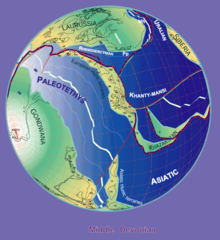

The Paleo-Tethys or Palaeo-Tethys Ocean was an ocean located along the northern margin of the paleocontinent Gondwana that started to open during the Middle Cambrian, grew throughout the Paleozoic, and finally closed during the Late Triassic; existing for about 400 million years.[2]

Paleo-Tethys was a precursor to the Tethys Ocean (also called the Neo-Tethys) which was located between Gondwana and the Hunic terranes (continental fragments that broke-off Gondwana and moved north). It opened as the Proto-Tethys Ocean subducted under these terranes and closed as the Cimmerian terranes (that also broke-off Gondwana and moved north) gave way to the Tethys Ocean.[3] Confusingly, the Neo-Tethys is sometimes defined as the ocean south of a hypothesised mid-ocean ridge separating Greater India from Asia, in which case the ocean between Cimmeria and this hypothesised ridge is called the Meso-Tethys, i.e. the "Middle-Tethys".[4]

The so-called Hunic terranes are divided into the European Hunic (today the crust under parts of Europe – called Armorica – and Iberia) and Asiatic Hunic (today the crust of parts of southern Asia). A large transform fault separated the two terranes.

The role the Paleo-Tethys played in the supercontinent cycle, and especially the break-up of Pangaea, is unresolved. Some geologists argue that the opening of the North Atlantic was triggered by the subduction of Panthalassa under the western margins of the Americas while other argue that the closure of the Paleo-Tethys and Tethys resulted in the break-up. In the first scenario, mantle plumes caused the opening of the Atlantic and the break-up of Pangaea and the closure of the Tethyan domain was one of the consequences of this process; in the other scenario, the longitudinal forces that closed the Tethyan domain were transmitted latitudinally in what is today the Mediterranean region, resulting in the initial opening of the Atlantic.[5]

History

editThe Paleo-Tethys Ocean began to form when back-arc spreading separated the European Hunic terranes from Gondwana in the late Ordovician, to begin moving toward Euramerica (also known as the Old Red Sandstone Continent) in the north. In the process, the plate under the Rheic Ocean between Euramerica and the European Hunic terranes subducted and rifts in this plate resulted in the formation of a small Rhenhercynian Ocean which lasted until Late Carboniferous time.[6][7]

In the Early Devonian, the eastern part of Paleo-Tethys opened up, when the Asiatic Hunic terranes, including the North and South China microcontinents, moved northward.[7][8]

These events caused Proto-Tethys Ocean to shrink until the Late Carboniferous, when the Chinese blocks collided with Siberia.[7] In the Early Carboniferous however, a subduction zone developed south of the European Hunic terranes consuming Paleo-Tethys oceanic crust. [9] Gondwana started moving north, and in the process the western part of the Paleo-Tethys would close.[7][10]

In the Carboniferous continental collision took place between the Old Red Sandstone Continent and the European Hunic terrane, in North America this is called the Alleghenian orogeny, in Europe the Variscan orogeny. The Rheic Ocean had completely disappeared, and the western Paleo-Tethys was closing.

By the Late Permian, the small elongated Cimmerian plate (today's crust of Turkey, Iran, Tibet and parts of South-East Asia) broke away from Gondwana (now part of Pangaea). South of the Cimmerian continent a new ocean, the Tethys Ocean, was created. By the Late Triassic, all that was left of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean was a narrow seaway.

In the Early Jurassic epoch, as part of the Alpine Orogeny, the oceanic crust of the Paleo-Tethys subducted under the Cimmerian plate, closing the ocean from west to east. A last remnant of Paleo-Tethys Ocean might be an oceanic crust under the Black Sea. (Anatolia, to the sea's south, is a part of the original Cimmerian continent that formed the southern boundary of the Paleo-Tethys.)

The Paleo-Tethys Ocean sat where the Indian Ocean and Southern Asia are now located. The Equator ran the length of the sea, giving it a tropical climate. The shores and islands probably supported dense coal forests.

See also

edit- List of ancient oceans – List of Earth's former oceans

References

editNotes

edit- ^ Stampfli & Borel 2000 - Tethyan Plate Tectonic working group of the Institut of Mineralogy and Petrography, University of Lausanne

- ^ Zhai et al. 2015, Abstract

- ^ Muttoni et al. 2009, Fig. 2, p. 19

- ^ Müller & Seton 2015, p. 5

- ^ Keppie 2015a, Abstract; Keppie 2015b, Abstract

- ^ Stampfli, von Raumer & Borel 2002, Middle Devonian Phase, p. 272

- ^ a b c d Stampfli, von Raumer & Borel 2002, Fig. 3, pp. 268–629

- ^ Stampfli, von Raumer & Borel 2002, Hun Superterrane, p. 267

- ^ Stampfli, von Raumer & Borel 2002, European Hunic active margin in Armorica (sensu lato), p. 273

- ^ Stampfli, von Raumer & Borel 2002, Fig. 4e, p. 270

Sources

edit- Keppie, D. F. (2015a). "How the closure of paleo-Tethys and Tethys oceans controlled the early breakup of Pangaea". Geology. 43 (4): 335–338. Bibcode:2015Geo....43..335K. doi:10.1130/G36268.1.

- Keppie, F. (2015b). "How subduction broke up Pangaea with implications for the supercontinent cycle" (PDF). In Li, Z. X.; Evans, D. A. D.; Murphy, J. B. (eds.). Supercontinent Cycles Through Earth History. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. Vol. 424. pp. 265–288. doi:10.1144/SP424.8. S2CID 140610523. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Müller, R. D.; Seton, M. (2015). "Paleophysiography of Ocean Basins". In Harff, J.; Meschede, M.; Petersen, S.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Geosciences. Springer. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6644-0_84-1. ISBN 978-94-007-6237-4. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Muttoni, G.; Gaetani, M.; Kent, D. V.; Sciunnach, D.; Angiolini, L.; Berra, F.; Garzanti, E.; Mattei, M.; Zanchi, A. (2009). "Opening of the Neo-Tethys Ocean and the Pangea B to Pangea A transformation during the Permian" (PDF). GeoArabia. 14 (4): 17–48. Bibcode:2009GeoAr..14...17M. doi:10.2113/geoarabia140417. S2CID 53416016. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Stampfli, G. M.; von Raumer, J. F.; Borel, G. D. (2002). "Paleozoic evolution of pre-Variscan terranes: From Gondwana to the Variscan collision" (PDF). In Catalán, M.; Hatcher, R. D. Jr.; Arenas, R.; et al. (eds.). Variscan-Appalachian dynamics: The building of the late Paleozoic basement (PDF). Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America Special Paper 364. pp. 263–280. doi:10.1130/0-8137-2364-7.263. ISBN 9780813723648. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- Zhai, Q. G.; Jahn, B. M.; Wang, J.; Hu, P. Y.; Chung, S. L.; Lee, H. Y.; Tang, S. H.; Tang, Y. (2015). "Oldest Paleo-Tethyan ophiolitic mélange in the Tibetan Plateau". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 128 (B31296-1): 355–373. doi:10.1130/B31296.1.

External links

edit- Late Carboniferous Map - at PaleoMap Project; a good picture of Paleo-Tethys Ocean before the Cimmerian Plate moves northward.

- Paleo-Tethys and Proto-Tethys - at global history

- Video from Christopher R. Scotese: Paleotethys - Indian subkontinent