The Pacific ladyfish (Elops affinis), also known as the Pacific tenpounder and machete, is a species of ray-finned fish in the genus Elops, the only genus in the monotypic family Elopidae. The Pacific ladyfish can be found throughout the southwest U.S. and other areas in the Pacific Ocean.[2][3][4][5][6]

| Pacific ladyfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Elopiformes |

| Family: | Elopidae |

| Genus: | Elops |

| Species: | E. affinis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Elops affinis Regan, 1909

| |

Description

editThe Pacific ladyfish have very round bodies with terminal mouths, and profound gill formations known as pseudobranchiae. They have a larger number of dorsal fin rays than most Arizona fish,[5] with numbers ranging from 27 to 35. Anal fin rays usually range from 13 to 19, and they have 12 to 16 pelvic rays. This species is very different from most chordates in that it has no conus arteriosus, a tendinous band of tissue from which the pulmonary artery arises. Because of this absence, they have a much smaller pulmonary artery. This fish's lateral lines are unbranched, and lateral line scales are usually within ranges of 95 to 120. All scales are silvery and cycloid, along with the overall color of the fish; however, yellow pigment can occur in the eyes. Some aids to identification include the prominent auxiliary and inguinal processes.[4]

Distribution and habitat in Arizona

editThis species is restricted primarily to the Southwest United States.[4] Most records come from the Colorado River Delta and the Gulf of California, as they spawn here and then travel southwest into Arizona. They were also common in the Salton Sea in California, but their numbers have been slowly declining. During floods, Pacific ladyfish enter the Lower Colorado River from the Gulf. They can be found in Yuma Colorado River portions, with records as far south as certain Mexican dams. Pacific tenpounders are primarily a marine form, meaning they require a higher salinity water content then most freshwater fish. Because of this, they have evolved efficient swimming techniques allowing them to swim in lagoons and estuaries with higher salinities. Their maximum depth is around 10 m (33 ft).[3]

Reproduction

editThis species uses a wide range of water salinities when spawning. Under normal conditions, the Pacific tenpounder are located in brackish water, but they travel deep into oceanic, salty waters for breeding. They place their eggs far from shore in more planktonic regions to provide them with nutrients as juveniles.[2] The larvae look like eels at birth, but their forked tails distinguish them. Their young usually feed on the crustaceans in the brackish or coastal waters. This may explain their instinct to move from the Gulf of California into the Lower Colorado during flood conditions.[4]

Biology

editPacific ladyfish are pelagic, marine forms preferring either brackish or fresh water unless they are breeding. They prefer specific water depths of no more than 8 m (26 ft). Little is known about the ecology of this species, but they are known to be highly carnivorous, feeding on smaller fish and crustaceans.[2] This behavior is very similar to their relative, the Atlantic ladyfish. Maximum size is relatively larger than most Arizona fish, reaching lengths of 1 m (3 ft 3 in). A negative correlation exists between size and presence in the Colorado River. As they become larger in size, they enter more brackish waters for unknown reasons. Larval and juvenile stages of fish have large records of distribution near Rocky Point, in the Sea of Cortez tidal inlets. Their spawning areas are usually closer to coastal areas, because they use saltier waters for their young.[4]

Threats

editThis species uses estuarine areas and hypersaline lagoons; changes in the quality of these habitats may affect this species' population dynamics. Although this species may not be closely associated with any single habitat, it may be adversely affected by development and urbanization.[7]

References

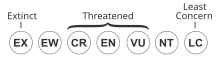

edit- ^ Adams, A.; Guindon, K.; Horodysky, A.; MacDonald, T.; McBride, R.; Shenker, J.; Ward, R. (2019). "Elops affinis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T184047A129624927. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T184047A129624927.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Battaso, R. H. and J. N. Young. (1999). Evidence for freshwater spawning by striped mullet and return of Pacific tenpounder in the lower Colorado River. California Fish & Game. 85(2): pp 75-76.

- ^ a b Forey, P. L. (1973). A revision of the elopiform fishes, fossil and recent. Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History (Geology) Supplement 10. pp. 222.

- ^ a b c d e Froese, R. and D. Pauly, Editors. 2002. Elops affinis. FishBase. 24 September 2002.

- ^ a b Nelson, J. S. Fishes of the World. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York. 1994. pp. 99, 100.

- ^

- Eschmeyer, W.N., et al. A Field Guide to Pacific Coast Fishes of North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, USA. 1983. page 336.

- Minckley, W. L. 1973. Fishes of Arizona. Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix. pp. 46-47.

- Nelson, J. S. Fishes of the World. Wiley-Interscience Publication, John Wiley and Sons. 1984. pp. 523.

- ^ Adams, A. J., et al. (2014). Global conservation status and research needs for tarpons (Megalopidae), ladyfishes (Elopidae) and bonefishes (Albulidae). Fish and Fisheries 15(2) 280-311.