Oscar Johannes Ludwig Eckenstein (9 September 1859 – 8 April 1921) was an English rock climber and mountaineer, and a pioneer in the sport of bouldering. Inventor of the modern crampon,[1] he was an innovator in climbing technique and mountaineering equipment, and the leader of the first serious expedition to attempt K2.

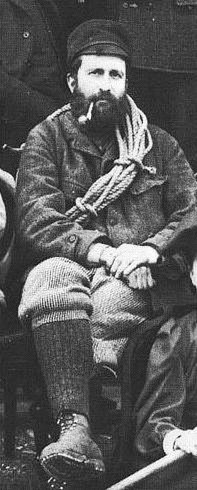

Eckenstein in the 1890s | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | 9 September 1859 |

| Died | 8 April 1921 (aged 61) Oving, Bucks, England |

| Occupation(s) | rock climber, mountaineer, engineer |

| Spouse | Margery Edwards (1918) |

| Relative | Lina Eckenstein (sister) |

| Climbing career | |

| Known for | leader of the first serious expedition to attempt K2, (1902) |

Background

editEckenstein's father was a Jewish socialist from Bonn who had fled the Kingdom of Prussia following the failed revolution of 1848. His mother was English.

His sisters were Lina Eckenstein, the polymath feminist,[2] and Amelia who was to marry Julius Cyriax.

He was a railway engineer and worked for the International Railway Congress Association founded in Brussels in 1885. He was an early and active member of the National Liberal Club. Interested in the life of explorer Richard Burton, he collected an extensive collection of documents about his life, which he donated to the Royal Asiatic Society before his death.

In 1918 O.E. married Margery Edwards. There were no children.

Rock climbing in the United Kingdom

editEckenstein climbed in the English Lake District with George and Ashley Abraham, though their relationship was not always smooth, and in North Wales with Geoffrey Winthrop Young and J. M. Archer Thomson. An early advocate of bouldering, on the Eckenstein Boulder at Llanberis Pass he taught Archer Thomson the art of balance climbing, according to Winthrop Young.

Mountaineering in the Alps

editTogether with Matthias Zurbriggen he made the first ascent of the Stecknadelhorn (4,241 m) in the Pennine Alps on 8 August 1887; on 10 July 1906, together with Karl Blodig and Alexis Brocherel, he made the first ascent of Mont Brouillard.[3]

Friendship with Aleister Crowley

editEckenstein was one of the few people who readily climbed with mystic and magician Aleister Crowley. In Crowley's autobiography, the Confessions, he mentions that they first met at Wasdale Head in 1898.[4] Crowley dedicated the Confessions to six men, including "OSCAR ECKENSTEIN – who trained me to follow the trail" and he praises Eckenstein in several passages of the book, mentioning his gymnastic strength, including his ability to do one-arm chin ups.[4] In 1900 Eckenstein travelled to Mexico to climb there with Crowley,[5] they also climbed together on the expedition led by Eckenstein to attempt K2 in 1902.

The Baltoro and K2

editEckenstein was a member of an expedition led by Sir Martin Conway to the Baltoro Muztagh region in 1892. The expedition was sponsored by the Royal Society, the Royal Geographical Society and the British Association, and included a young C.G.Bruce on his first major trek. Conway and Eckenstein had a deep personality conflict, and Eckenstein withdrew from the expedition after six months.[6][7] In Kashmir, he conducted bouldering contests for the natives – possibly the first such "formal" competitions ever. Eckenstein collected his letters and diary notes from this expedition into a book published under the title 'The Karakorams and Kashmir'.[8]

Eckenstein was the leader of the first serious attempt to climb K2 in 1902. The attempt was on the Northeast Ridge, Aleister Crowley and Guy Knowles were also members of the expedition. Upon arrival in India, Eckenstein was detained by British authorities for three weeks on suspicion of being a spy, and not allowed to enter Kashmir. He and Crowley were convinced that Martin Conway was responsible for trying to interfere with their attempt on K2, and only when they threatened to take the matter to the newspapers was Eckenstein released.[9]

In the early 1900s, modern transportation did not exist: It took "fourteen days just to reach the foot of the mountain".[10] After five serious and costly attempts, the team reached 6,525 metres (21,407 ft)[11] – although considering the difficulty of the challenge, and the lack of modern climbing equipment or weatherproof fabrics, Crowley's statement that "neither man nor beast was injured" highlights the pioneering spirit and bravery of the attempt. The failures were also attributed to sickness (Crowley was suffering the residual effects of malaria), a combination of questionable physical training, personality conflicts, and poor weather conditions – of 68 days spent on K2 (at the time, the record for the longest time spent at such an altitude) only eight provided clear weather.[12] An Austrian climber named Pfannl became sick with pulmonary edema at the high point, which Crowley diagnosed. The climb was abandoned, and Pfannl was evacuated to lower elevations and survived.[13]

Innovations in equipment and technique

editIn the late 19th century, the typical ice axe shaft measured 120–130 cm in length. Eckenstein started the trend toward shorter ice axes with a lighter model measuring 85–86 cm, which could be used single handed. Initially, this innovation was criticised by well-known climbers of the era, including his nemesis Martin Conway, a prominent member of the Alpine Club.[14] Eckenstein is also credited with designing the modern crampon as well as analysing both knots and nail patterns for climbing boots.

He was an advocate of guideless climbing in a period when conventional thinking in the Alpine Club called for gentlemen climbers to be led to the top of peaks by paid professional guides.

He assisted Geoffrey Winthrop Young with his classic mountaineering manual, Mountain Craft. John Percy Farrar and J. Norman Collie also contributed to this book. When the book was published in 1920, Farrar wrote to Winthrop Young: "The book is magnificent ... It will be standard for so long as mankind is interested in mountaineering. The profound amount of work put into it staggers me."[15]

Personality and conflict with the Alpine Club

editHe was a railway engineer for most of his life – well educated, and insufferably arrogant (some said).[16] He was not one to mince words, and a long feud with the Alpine Club[17] caused many of its members to denigrate him.

Later life

editEckenstein married Margery Edwards in February 1918, when he was 58. They lived in the small town of Oving. His health soon declined and he died of consumption in 1921.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Rowell, Galen (1977). In The Throne Room of the Mountain Gods. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. pp. 36. ISBN 978-0-87156-184-8.

- ^ Sybil Oldfield, 'Eckenstein, Lina Dorina Johanna (1857–1931)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2014 accessed 1 October 2015

- ^ Dumler, Helmut and Burkhardt, Willi P., The High Mountains of the Alps, London: Diadem, 1993, p. 198

- ^ a b Crowley, Aleister (1969). The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Jonathan Cape. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Eckenstein, Oscar (1903). "Mountaineering in Mexico" (PDF). Climbers Club Journal. #5 (20): 159–167. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ Rowell, Galen (1977). In The Throne Room of the Mountain Gods. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-87156-184-8.

- ^ a b Dean, David; Blakeney, T.S.; Dangar, D.F.O. (1960). "Oscar Eckenstein, 1859-1921" (PDF). Alpine Journal. #65 (300): 62–79. ISSN 0065-6569. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Eckenstein, Oscar (1896). The Karakorams and Kashmir. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp. 1–253. ISBN 978-1-110-86203-0.

- ^ Rowell, Galen (1977). In The Throne Room of the Mountain Gods. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-87156-184-8.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (1979). The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography. London; Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-0175-4. Chapter 16.

- ^ A timeline of human activity on K2

- ^ Booth, Martin (2001) [2000]. "Rhythms of Rapture". A Magick Life: A Biography of Aleister Crowley (trade paperback) (Coronet ed.). London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 152–157. ISBN 978-0-340-71806-3.

- ^ Rowell, Galen (1977). In The Throne Room of the Mountain Gods. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. pp. 90. ISBN 978-0-87156-184-8.

- ^ Rowell, Galen (1977). In The Throne Room of the Mountain Gods. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. pp. 36–40. ISBN 978-0-87156-184-8.

- ^ Hankinson, Alan (1995). Geoffrey Winthrop Young: Poet, Educator, Mountaineer. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 224–233.

- ^ See Martin Booth, A Magick Life (2000), p.69.

- ^ Booth p.70: highly critical of the Alpine Club

- John Gill (2006). "Oscar Eckenstein . . . The First Documented Advocate of Bouldering".