Omaha–Ponca is a Siouan language spoken by the Omaha (Umoⁿhoⁿ) people of Nebraska and the Ponca (Paⁿka) people of Oklahoma and Nebraska. The two dialects differ minimally but are considered distinct languages by their speakers.[2]

| Omaha–Ponca | |

|---|---|

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Nebraska and Oklahoma |

| Ethnicity | 525 (365 Omaha, 160 Ponca, 2010 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 85 (2007)[1] |

Siouan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | oma |

| Glottolog | omah1247 |

| ELP | Omaha-Ponca |

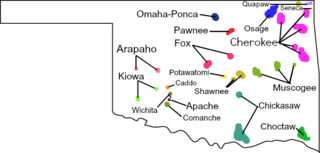

Map showing the distribution of Oklahoma Indian Languages | |

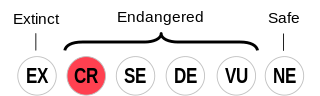

Omaha-Ponca is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

| People | Umoⁿhoⁿ, Páⁿka |

|---|---|

| Language | Iyé, Gáxe |

| Country | Umoⁿhoⁿ Mazhóⁿ, Páⁿka Mazhóⁿ |

Use and revitalization efforts

editThere are today only 60 speakers of Omaha, and 12 fluent speakers, all over 70; and a handful of semi-fluent speakers of Ponca.

The University of Nebraska offers classes in the Omaha language, and its Omaha Language Curriculum Development Project (OLCDP) provides Internet-based materials for learning the language.[3][4][5][6] A February 2015 article gives the number of fluent speakers as 12, all over age 70, which includes two qualified teachers; the Tribal Council estimates about 150 people have some ability in the language. The language is taught at the Umónhon Nation Public School.[7] An Omaha Basic iPhone app has been developed by the Omaha Nation Public Schools (UNPS) and the Omaha Language Cultural Center (ULCC).[8] Members of the Osage Nation of Oklahoma have expressed an interest in partnerships to use the language as a basis of revitalizing the Osage language, which is similar.[7] Louis Headman edited a dictionary of the Ponca People, published by the University of Nebraska Press.[9]

Phonology

editConsonants

edit| Labial | Dental | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Plosive | voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ | |

| voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | ʔ | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | ||

| ejective | pʼ | tʼ | ||||

| Fricative | voiced | z | ʒ | ɣ | ||

| voiceless | s | ʃ | x | |||

| glottalized | sʼ | ʃʼ | xʼ | |||

| Approximant | w | lᶞ | h | |||

Voiceless sounds /p, t, tʃ, k/ may also be heard as tense [pː, tː, tʃː, kː] in free variation.

One consonant, sometimes written l or th, is a velarized lateral approximant with interdental release, [ɫᶞ], found for example in ní btháska [ˌnĩ ˈbɫᶞaska] "flat water" (Platte River), the source of the name Nebraska. It varies freely from [ɫ] to a light [ð̞], and derives historically from Siouan *r.

Initial consonant clusters include approximates, as in /blᶞ/ and /ɡlᶞ/.

Consonants are written as in the IPA in school programs, apart from the alveopalatals j, ch, chʰ, zh, sh, shʼ, the glottal stop ’, the voiced velar fricative gh, and the dental approximant th. Historically, this th has also been written dh, ð, ¢, and the sh and x as c and q; the tenuis stops p t ch k have either been written upside-down or double (pp, kk, etc.). These latter unusual conventions serve to distinguish these sounds from the p t ch k of other Siouan languages, which are not specified for voicing and so may sound like either Omaha–Ponca p t ch k or b d j g. The letters f, l, q, r, v are not used in writing Omaha-Ponca.

Vowels

edit| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | oral | i | u |

| nasal | ĩ | ||

| Mid | oral | e | |

| Low | oral | a | (o) |

| nasal | ã | (õ) | |

The simple vowels are /a, e, i, u/, plus a few words with /o/ in men's speech. The letter ‘o’ is phonemically /au/, and phonetically [əw].[10]

There are two or three nasal vowels, depending on the variety. In the Omaha and Ponca Dhegiha dialects *õ and *ã have merged unconditionally as /õ/, which may range across [ã] ~ [õ] ~ [ũ] and is written ⟨oⁿ⟩ in Omaha and ⟨aⁿ⟩ in Ponca. The close front nasal vowel /ĩ/ remains distinct.

Nasalized vowels are fairly new to the Ponca language. Assimilation has taken place leftward, as opposed to right to left, from nasalized consonants over time. "Originally when the vowel was oral, it nasalized the consonant and a nasalized vowel never followed suit, instead, the nasalized vowel came to preceded it"; though this is not true for the Omaha, or its 'mother' language."[11]

Omaha/Ponca is a tonal language that utilizes downstep (accent) or a lowering process that applies to the second of two high-tone syllables. A downstepped high tone would be slightly lower than the preceding high tone.”: wathátʰe /walᶞaꜜtʰe/ "food", wáthatʰe /waꜜlᶞatʰe/ "table". Vowel length is distinctive in accented syllables, though it is often not written: [nãːꜜde] "heart", [nãꜜde] "(inside) wall".[12]

Omaha-Ponca is a daughter language to the Siouan mother language, but has developed some of its own rules for nasalization and aspiration. What were once allophones in Proto-Siouan have become phonemes in the Omaha–Ponca language.

Many contrasts in the Omaha/Ponca language are unfamiliar to speakers of English.[13] Below are examples of minimal pairs for some sounds which in English would be considered allophones, but in Omaha/Ponca constitute different phonemes:

| Contrast | Word | Gloss | Word | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [p] vs. [pʰ] | [pa] | head/nose | [pʰa] | bitter |

| [i] vs. [ĩ] | [nazhi] | to go out | [nazhĩ́] | to stand |

| [t] vs. [tʼ] | [tṍde] | the ground | [t’ṍde] | during future early autumns |

In many languages nasalization of vowels would be a part of assimilation to the next consonant, but Omaha/Ponca is different because it is always assimilating.[clarification needed] For example: iⁿdáthiⁿga, meaning mysterious, moves from a nasalized /i/ to an alveolar, stop. Same thing happens with the word iⁿshte, meaning, for example, has the nasalized /i/ which does not assimilate to another nasal. It changes completely to an alveolar fricative.

Morphology

editOmaha Ponca language adds endings to its definite articles to indicate animacy, number, position and number. Ponca definite articles indicate animacy, position and number.[14]

| morphological ending | gloss meaning |

|---|---|

| -kʰe | for inanimate horizontal object |

| -tʰe | for inanimate standing object |

| -ðaⁿ | for inanimate round object |

| akʰá | for singular animate agent |

| -amá | for singular animate agent in motion or plural |

| -tʰaⁿ | for animate singular patient in standing position |

| ðiⁿ | for animate singular patient in motion |

| -ma | for animate plural patient in motion |

| -ðiⁿkʰé | for animate singular patient in sitting position |

| -ðaⁿkʰá | for animate plural patient in sitting position |

Syntax

editOmaha-Ponca's syntactic type is subject-object-verb.[15]

Notes

edit- ^ a b Omaha–Ponca at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Rudin & Shea (2006) "Omaha–Ponca", in the Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics

- ^ Overmyer, Krystal (2003-12-13). "Omaha language classes keep culture alive". Canku Ota. Archived from the original on 2014-06-12. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Abourezk, Kevin (2011-10-09). "Woman travels 1,100 miles to learn Omaha language". The Lincoln Journal Star Online. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Florio, Gwen. "Culture-thief? Or help to tribe? Non-Native American Omaha language teacher stirs debate". The Buffalo Post. Archived from the original on 2014-09-14. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ "Omaha Language Curriculum Development Project". Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ a b Peters, Chris (2015-02-15). "Omaha Tribe members trying to revitalize an 'endangered language'". Omaha.com: Living. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- ^ "Omaha Basic on the App Store on iTunes". iTunes Preview. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- ^ "Louis V. Headman to receive Honorary Doctorate at Bacone College Spring 2021 Commencement". Ponca City News. April 14, 2021. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021.

- ^ Bruce, Benjamin. "Ponca Alphabet Archived 2011-11-06 at the Wayback Machine." The Hello Oklahoma! Project. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

- ^ Michaud, Alexis. "Historical Transfer of Nasality between Consonantal Onset and Vowel." Diachronica 2012th ser. 29.2 (2011): 1-34. Web. 26 Oct. 2011.

- ^ Crystal, David. A Dictionary of Linguistics & Phonetics. 5th ed. Blackwell, 2003. Print.

- ^ Omaha Ponca Dictionary Index

- ^ Finegan, Edward, and John R. Rickford. Language in the USA: Themes for the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. Print. (page 171)

- ^ Syntax

References

edit- Boas, Franz. "Notes on the Ponka grammar", Congrès international des américanistes, Proceedings 2:217-37.

- Dorsey, James Owen. Omaha and Ponka Letters. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891

- Dorsey, James Owen. The Cegiha Language. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1890

- Dorsey, Rev. J. Owen Omaha Sociology. Washington: Smithsonian, Bureau of American Ethnology, Report No. 3, 1892–1893

- List of basic references on Omaha-Ponca

External links

edit- Omaha-Ponca Indian Language (Cegiha, Dhegiha), native-language.org

- "Omaha Language Curriculum Development Project". Retrieved 2013-08-15.. Extensive language learning materials, including audio.

- Omaha Ponca dictionary

- "Omaha Ponca grammar". Omaha Ponca Sketch. Archived from the original on 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- OLAC resources in and about the Omaha-Ponca language

- Chairman Elmer Blackbird Delivers Introduction (in Omaha-Ponca) .mp3

- Ponca Hymns sung by the congregation of White Eagle United Methodist Church