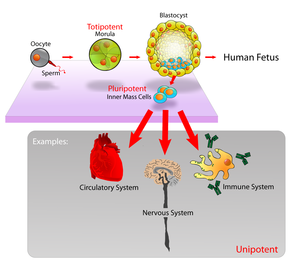

Cell potency is a cell's ability to differentiate into other cell types.[1][2] The more cell types a cell can differentiate into, the greater its potency. Potency is also described as the gene activation potential within a cell, which like a continuum, begins with totipotency to designate a cell with the most differentiation potential, pluripotency, multipotency, oligopotency, and finally unipotency.

Totipotency

editTotipotency (Latin: totipotentia, lit. 'ability for all [things]') is the ability of a single cell to divide and produce all of the differentiated cells in an organism. Spores and zygotes are examples of totipotent cells.[3] In the spectrum of cell potency, totipotency represents the cell with the greatest differentiation potential, being able to differentiate into any embryonic cell, as well as any extraembryonic tissue cell. In contrast, pluripotent cells can only differentiate into embryonic cells.[4][5]

A fully differentiated cell can return to a state of totipotency.[6] The conversion to totipotency is complex and not fully understood. In 2011, research revealed that cells may differentiate not into a fully totipotent cell, but instead into a "complex cellular variation" of totipotency.[7]

The human development model can be used to describe how totipotent cells arise.[8] Human development begins when a sperm fertilizes an egg and the resulting fertilized egg creates a single totipotent cell, a zygote.[9] In the first hours after fertilization, this zygote divides into identical totipotent cells, which can later develop into any of the three germ layers of a human (endoderm, mesoderm, or ectoderm), or into cells of the placenta (cytotrophoblast or syncytiotrophoblast). After reaching a 16-cell stage, the totipotent cells of the morula differentiate into cells that will eventually become either the blastocyst's Inner cell mass or the outer trophoblasts. Approximately four days after fertilization and after several cycles of cell division, these totipotent cells begin to specialize. The inner cell mass, the source of embryonic stem cells, becomes pluripotent.

Research on Caenorhabditis elegans suggests that multiple mechanisms including RNA regulation may play a role in maintaining totipotency at different stages of development in some species.[10] Work with zebrafish and mammals suggest a further interplay between miRNA and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) in determining development differences.[11]

Primordial germ cells

editIn mouse primordial germ cells, genome-wide reprogramming leading to totipotency involves erasure of epigenetic imprints. Reprogramming is facilitated by active DNA demethylation involving the DNA base excision repair enzymatic pathway.[12] This pathway entails erasure of CpG methylation (5mC) in primordial germ cells via the initial conversion of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), a reaction driven by high levels of the ten-eleven dioxygenase enzymes TET-1 and TET-2.[13]

Pluripotency

editB: Nerve cells

In cell biology, pluripotency (Latin: pluripotentia, lit. 'ability for many [things]')[14] refers to a stem cell that has the potential to differentiate into any of the three germ layers: endoderm (gut, lungs and liver), mesoderm (muscle, skeleton, blood vascular, urogenital, dermis), or ectoderm (nervous, sensory, epidermis), but not into extra-embryonic tissues like the placenta or yolk sac.[15]

Induced pluripotency

editInduced pluripotent stem cells, commonly abbreviated as iPS cells or iPSCs, are a type of pluripotent stem cell artificially derived from a non-pluripotent cell, typically an adult somatic cell, by inducing a "forced" expression of certain genes and transcription factors.[16] These transcription factors play a key role in determining the state of these cells and also highlights the fact that these somatic cells do preserve the same genetic information as early embryonic cells.[17] The ability to induce cells into a pluripotent state was initially pioneered in 2006 using mouse fibroblasts and four transcription factors, Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc;[18] this technique, called reprogramming, later earned Shinya Yamanaka and John Gurdon the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[19] This was then followed in 2007 by the successful induction of human iPSCs derived from human dermal fibroblasts using methods similar to those used for the induction of mouse cells.[20] These induced cells exhibit similar traits to those of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) but do not require the use of embryos. Some of the similarities between ESCs and iPSCs include pluripotency, morphology, self-renewal ability, a trait that implies that they can divide and replicate indefinitely, and gene expression.[21]

Epigenetic factors are also thought to be involved in the actual reprogramming of somatic cells in order to induce pluripotency. It has been theorized that certain epigenetic factors might actually work to clear the original somatic epigenetic marks in order to acquire the new epigenetic marks that are part of achieving a pluripotent state. Chromatin is also reorganized in iPSCs and becomes like that found in ESCs in that it is less condensed and therefore more accessible. Euchromatin modifications are also common which is also consistent with the state of euchromatin found in ESCs.[21]

Due to their great similarity to ESCs, the medical and research communities are interested iPSCs. iPSCs could potentially have the same therapeutic implications and applications as ESCs but without the controversial use of embryos in the process, a topic of great bioethical debate. The induced pluripotency of somatic cells into undifferentiated iPS cells was originally hailed as the end of the controversial use of embryonic stem cells. However, iPSCs were found to be potentially tumorigenic, and, despite advances,[16] were never approved for clinical stage research in the United States until recently. Currently, autologous iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitor cells are used in trials for treating Parkinson's disease.[22] Setbacks such as low replication rates and early senescence have also been encountered when making iPSCs,[23] hindering their use as ESCs replacements.

Somatic expression of combined transcription factors can directly induce other defined somatic cell fates (transdifferentiation); researchers identified three neural-lineage-specific transcription factors that could directly convert mouse fibroblasts (connective tissue cells) into fully functional neurons.[24] This result challenges the terminal nature of cellular differentiation and the integrity of lineage commitment; and implies that with the proper tools, all cells are totipotent and may form all kinds of tissue.

Some of the possible medical and therapeutic uses for iPSCs derived from patients include their use in cell and tissue transplants without the risk of rejection that is commonly encountered. iPSCs can potentially replace animal models unsuitable as well as in vitro models used for disease research.[25]

Naive vs. primed pluripotency states

editFindings with respect to epiblasts before and after implantation have produced proposals for classifying pluripotency into two states: "naive" and "primed", representing pre- and post-implantation epiblast, respectively.[26] Naive-to-primed continuum is controlled by reduction of Sox2/Oct4 dimerization on SoxOct DNA elements controlling naive pluripotency.[27] Primed pluripotent stem cells from different species could be reset to naive state using a cocktail containing Klf4 and Sox2 or "super-Sox" − a chimeric transcription factor with enhanced capacity to dimerize with Oct4.[27]

The baseline stem cells commonly used in science that are referred as embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are derived from a pre-implantation epiblast; such epiblast is able to generate the entire fetus, and one epiblast cell is able to contribute to all cell lineages if injected into another blastocyst. On the other hand, several marked differences can be observed between the pre- and post-implantation epiblasts, such as their difference in morphology, in which the epiblast after implantation changes its morphology into a cup-like shape called the "egg cylinder" as well as chromosomal alteration in which one of the X-chromosomes under random inactivation in the early stage of the egg cylinder, known as X-inactivation.[28] During this development, the egg cylinder epiblast cells are systematically targeted by Fibroblast growth factors, Wnt signaling, and other inductive factors via the surrounding yolk sac and the trophoblast tissue,[29] such that they become instructively specific according to the spatial organization.[30]

Another major difference is that post-implantation epiblast stem cells are unable to contribute to blastocyst chimeras,[31] which distinguishes them from other known pluripotent stem cells. Cell lines derived from such post-implantation epiblasts are referred to as epiblast-derived stem cells, which were first derived in laboratory in 2007. Both ESCs and EpiSCs are derived from epiblasts but at difference phases of development. Pluripotency is still intact in the post-implantation epiblast, as demonstrated by the conserved expression of Nanog, Fut4, and Oct-4 in EpiSCs,[32] until somitogenesis and can be reversed midway through induced expression of Oct-4.[33]

Native pluripotency in plants

editUn-induced pluripotency has been observed in root meristem tissue culture, especially by Kareem et al 2015, Kim et al 2018, and Rosspopoff et al 2017. This pluripotency is regulated by various regulators, including PLETHORA 1 and PLETHORA 2; and PLETHORA 3, PLETHORA 5, and PLETHORA 7, whose expression were found by Kareem to be auxin-provoked. (These are also known as PLT1, PLT2, PLT3, PLT5, PLT7, and expressed by genes of the same names.) As of 2019[update], this is expected to open up future research into pluripotency in root tissues.[34]

Multipotency

editMultipotency is when progenitor cells have the gene activation potential to differentiate into discrete cell types. For example, a hematopoietic stem cell – and this cell type can differentiate itself into several types of blood cell like lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, etc., but it is still ambiguous whether HSC possess the ability to differentiate into brain cells, bone cells or other non-blood cell types.[citation needed]

Research related to multipotent cells suggests that multipotent cells may be capable of conversion into unrelated cell types. In another case, human umbilical cord blood stem cells were converted into human neurons.[35] There is also research on converting multipotent cells into pluripotent cells.[36]

Multipotent cells are found in many, but not all human cell types. Multipotent cells have been found in cord blood,[37] adipose tissue,[38] cardiac cells,[39] bone marrow, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) which are found in the third molar.[40]

MSCs may prove to be a valuable source for stem cells from molars at 8–10 years of age, before adult dental calcification. MSCs can differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes.[41]

Oligopotency

editIn biology, oligopotency is the ability of progenitor cells to differentiate into a few cell types. It is a degree of potency. Examples of oligopotent stem cells are the lymphoid or myeloid stem cells.[2] A lymphoid cell specifically, can give rise to various blood cells such as B and T cells, however, not to a different blood cell type like a red blood cell.[42] Examples of progenitor cells are vascular stem cells that have the capacity to become both endothelial or smooth muscle cells.

Unipotency

editIn cell biology, a unipotent cell is the concept that one stem cell has the capacity to differentiate into only one cell type.[43] It is currently unclear if true unipotent stem cells exist. Hepatoblasts, which differentiate into hepatocytes (which constitute most of the liver) or cholangiocytes (epithelial cells of the bile duct), are bipotent.[44] A close synonym for unipotent cell is precursor cell.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Cell totipotency was discovered by Habertland and the term was coined by Thomas Hund Morgan. Mahla RS (2016). "Stem Cells Applications in Regenerative Medicine and Disease Therapeutics". International Journal of Cell Biology. 2016 (7): 6940283. doi:10.1155/2016/6940283. PMC 4969512. PMID 27516776.

- ^ a b Schöler HR (2007). "The Potential of Stem Cells: An Inventory". In Knoepffler M, Schipanski D, Sorgner SL (eds.). Human biotechnology as Social Challenge. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7546-5755-2.

- ^ Mitalipov S, Wolf D (2009). "Totipotency, pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming". Engineering of Stem Cells. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. Vol. 114. pp. 185–199. Bibcode:2009esc..book..185M. doi:10.1007/10_2008_45. ISBN 978-3-540-88805-5. PMC 2752493. PMID 19343304.

- ^ Lodish H (2016). Molecular Cell Biology (8th ed.). W. H. Freeman. pp. 975–977. ISBN 978-1319067748.

- ^ "What is the difference between totipotent, pluripotent, and multipotent?".

- ^ Western P (2009). "Foetal germ cells: striking the balance between pluripotency and differentiation". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 53 (2–3): 393–409. doi:10.1387/ijdb.082671pw. PMID 19412894.

- ^ Sugimoto K, Gordon SP, Meyerowitz EM (April 2011). "Regeneration in plants and animals: dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation, or just differentiation?". Trends in Cell Biology. 21 (4): 212–218. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.004. PMID 21236679.

- ^ Seydoux G, Braun RE (December 2006). "Pathway to totipotency: lessons from germ cells". Cell. 127 (5): 891–904. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.016. PMID 17129777. S2CID 16988032.

- ^ Asch R, Simerly C, Ord T, Ord VA, Schatten G (July 1995). "The stages at which human fertilization arrests: microtubule and chromosome configurations in inseminated oocytes which failed to complete fertilization and development in humans". Human Reproduction. 10 (7): 1897–1906. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136204. PMID 8583008.

- ^ Ciosk R, DePalma M, Priess JR (February 2006). "Translational regulators maintain totipotency in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline". Science. 311 (5762): 851–853. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..851C. doi:10.1126/science.1122491. PMID 16469927. S2CID 130017.

- ^ Kedde M, Agami R (April 2008). "Interplay between microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins determines developmental processes". Cell Cycle. 7 (7): 899–903. doi:10.4161/cc.7.7.5644. PMID 18414021.

- ^ Hajkova P, Jeffries SJ, Lee C, Miller N, Jackson SP, Surani MA (July 2010). "Genome-wide reprogramming in the mouse germ line entails the base excision repair pathway". Science. 329 (5987): 78–82. Bibcode:2010Sci...329...78H. doi:10.1126/science.1187945. PMC 3863715. PMID 20595612.

- ^ Hackett JA, Sengupta R, Zylicz JJ, Murakami K, Lee C, Down TA, Surani MA (January 2013). "Germline DNA demethylation dynamics and imprint erasure through 5-hydroxymethylcytosine". Science. 339 (6118): 448–452. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..448H. doi:10.1126/science.1229277. PMC 3847602. PMID 23223451.

- ^ "Biology Online". Biology-Online.org. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Nobutaka, Windhorst U, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3540237358.

- ^ a b Baker M (2007-12-06). "Adult cells reprogrammed to pluripotency, without tumors". Nature Reports Stem Cells: 1. doi:10.1038/stemcells.2007.124.

- ^ Stadtfeld M, Hochedlinger K (October 2010). "Induced pluripotency: history, mechanisms, and applications". Genes & Development. 24 (20): 2239–2263. doi:10.1101/gad.1963910. PMC 2956203. PMID 20952534.

- ^ Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (August 2006). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–676. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. hdl:2433/159777. PMID 16904174. S2CID 1565219.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2012". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2013. Web. 28 Nov 2013.

- ^ Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S (November 2007). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors". Cell. 131 (5): 861–872. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. hdl:2433/49782. PMID 18035408. S2CID 8531539.

- ^ a b Liang G, Zhang Y (January 2013). "Embryonic stem cell and induced pluripotent stem cell: an epigenetic perspective". Cell Research. 23 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1038/cr.2012.175. PMC 3541668. PMID 23247625.

- ^ Schweitzer JS, Song B, Herrington TM, Park TY, Lee N, Ko S, et al. (May 2020). "Personalized iPSC-Derived Dopamine Progenitor Cells for Parkinson's Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (20): 1926–1932. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915872. PMC 7288982. PMID 32402162.

- ^ Choi, Charles. "Cell-Off: Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Fall Short of Potential Found in Embryonic Version". Scientific American. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC, Wernig M (February 2010). "Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors". Nature. 463 (7284): 1035–1041. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1035V. doi:10.1038/nature08797. PMC 2829121. PMID 20107439.

- ^ Park IH, Lerou PH, Zhao R, Huo H, Daley GQ (2008). "Generation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells". Nature Protocols. 3 (7): 1180–1186. doi:10.1038/nprot.2008.92. PMID 18600223. S2CID 13321484.

- ^ Nichols J, Smith A (June 2009). "Naive and primed pluripotent states". Cell Stem Cell. 4 (6): 487–492. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. PMID 19497275.

- ^ a b MacCarthy, Caitlin M.; Wu, Guangming; Malik, Vikas; Menuchin-Lasowski, Yotam; Velychko, Taras; Keshet, Gal; Fan, Rui; Bedzhov, Ivan; Church, George M.; Jauch, Ralf; Cojocaru, Vlad; Schöler, Hans R.; Velychko, Sergiy (December 2023). "Highly cooperative chimeric super-SOX induces naive pluripotency across species". Cell Stem Cell. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2023.11.010.

- ^ Heard E (June 2004). "Recent advances in X-chromosome inactivation". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 16 (3): 247–255. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.005. PMID 15145348.

- ^ Beddington RS, Robertson EJ (January 1999). "Axis development and early asymmetry in mammals". Cell. 96 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80560-7. PMID 9988215. S2CID 16264083.

- ^ Lawson KA, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA (November 1991). "Clonal analysis of epiblast fate during germ layer formation in the mouse embryo". Development. 113 (3): 891–911. doi:10.1242/dev.113.3.891. PMID 1821858. S2CID 17685207.

- ^ Rossant J (February 2008). "Stem cells and early lineage development". Cell. 132 (4): 527–531. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.039. PMID 18295568. S2CID 14128314.

- ^ Brons IG, Smithers LE, Trotter MW, Rugg-Gunn P, Sun B, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, et al. (July 2007). "Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos". Nature. 448 (7150): 191–195. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..191B. doi:10.1038/nature05950. PMID 17597762. S2CID 4365390.

- ^ Osorno R, Tsakiridis A, Wong F, Cambray N, Economou C, Wilkie R, et al. (July 2012). "The developmental dismantling of pluripotency is reversed by ectopic Oct4 expression". Development. 139 (13): 2288–2298. doi:10.1242/dev.078071. PMC 3367440. PMID 22669820.

- ^ Ikeuchi M, Favero DS, Sakamoto Y, Iwase A, Coleman D, Rymen B, Sugimoto K (April 2019). "Molecular Mechanisms of Plant Regeneration". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 70 (1). Annual Reviews: 377–406. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100434. PMID 30786238. S2CID 73498853.

- ^ Giorgetti A, Marchetto MC, Li M, Yu D, Fazzina R, Mu Y, et al. (July 2012). "Cord blood-derived neuronal cells by ectopic expression of Sox2 and c-Myc". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12556–12561. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912556G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209523109. PMC 3412010. PMID 22814375.

- ^ Guan K, Nayernia K, Maier LS, Wagner S, Dressel R, Lee JH, et al. (April 2006). "Pluripotency of spermatogonial stem cells from adult mouse testis". Nature. 440 (7088): 1199–1203. Bibcode:2006Natur.440.1199G. doi:10.1038/nature04697. PMID 16565704. S2CID 4350560.

- ^ Zhao Y, Mazzone T (December 2010). "Human cord blood stem cells and the journey to a cure for type 1 diabetes". Autoimmunity Reviews. 10 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2010.08.011. PMID 20728583.

- ^ Tallone T, Realini C, Böhmler A, Kornfeld C, Vassalli G, Moccetti T, et al. (April 2011). "Adult human adipose tissue contains several types of multipotent cells". Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research. 4 (2): 200–210. doi:10.1007/s12265-011-9257-3. PMID 21327755. S2CID 36604144.

- ^ Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, et al. (September 2003). "Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration". Cell. 114 (6): 763–776. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00687-1. PMID 14505575. S2CID 15588806.

- ^ Ohgushi H, Arima N, Taketani T (December 2011). "[Regenerative therapy using allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells]". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine (in Japanese). 69 (12): 2121–2127. PMID 22242308.

- ^ Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V (September 2008). "Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 8 (9): 726–736. doi:10.1038/nri2395. PMID 19172693. S2CID 3347616.

- ^ Ibelgaufts, Horst. "Cytokines & Cells Online Pathfinder Encyclopedia". Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (June 8, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 3.5 Cell Growth and Division. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

- ^ "hepatoblast differentiation". GONUTS. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-08-31.