Ocean Avenue is the fourth studio album by American rock band Yellowcard. It was released on July 22, 2003, through Capitol Records. After touring to promote their third album One for the Kids in 2001, the band signed to the label in early 2002. Following this, bassist Warren Cooke left the band in mid-2002, and was replaced by Inspection 12 guitarist Peter Mosely. In February and March 2003, the band recorded at Sunset Sound in Hollywood, California, with Neal Avron. Ocean Avenue is a pop-punk and punk rock album, which was compared to Blink-182 and Simple Plan.

| Ocean Avenue | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | July 22, 2003 | |||

| Recorded | February–March 2003 | |||

| Studio | Sunset Sound, Hollywood, California | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 47:26 | |||

| Label | Capitol | |||

| Producer | Neal Avron | |||

| Yellowcard chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Ocean Avenue | ||||

| ||||

Before Yellowcard's promotional tour of Ocean Avenue, Mosely was replaced by Alex Lewis. Yellowcard appeared on the Warped Tour, during which "Way Away" was released as the album's lead single on July 22, 2003. The band went on a club tour of the United States, before going on tour with Less Than Jake and Fall Out Boy. "Ocean Avenue" was released as the second single on December 16, 2003. Lewis departed from the band and was replaced by Mosely before a co-headlining tour with Something Corporate and a stint in Europe. "Only One" was released as the third and final single in June 2004; they toured Europe, Australia, and Japan. After this, they had a US tour.

Ocean Avenue received mostly positive reviews from music critics, some of whom commented on Sean Mackin's violin playing and songwriting quality. The album peaked at number 23 on the US Billboard 200, as well as number 8 in New Zealand, and number 149 in the UK. The album was certified platinum in the US by the RIAA, gold in Canada by Music Canada, and silver in the UK by the BPI. "Way Away" and "Only One" appeared high on the US Alternative Airplay chart; "Ocean Avenue" peaked at number 37 on the US Hot 100, and within the top 100 in Scotland and the UK alongside "Way Away". "Ocean Avenue" was certified double platinum by the RIAA and silver by the BPI. "Only One" was certified gold in the US.

In the years following its release, the album has received retrospective acclaim and is widely viewed as one of the greatest pop-punk albums of all time.[1][2][3]

Background and production

editIn April 2001,[4] Yellowcard released their third studio album One for the Kids through Lobster Records.[5] It was promoted with a tour of the southern United States with Inspection 12,[6] and a two-week tour of the US West Coast with Bordem.[7] Yellowcard had moved from Florida to California, with the hopes of someone from a label would be attached to them.[8] Harper said their manager was adamant about finding them a different label, and made pitches to a number of labels.[9] By April 2002, it was reported that the band had signed to Capitol Records,[10] one of a few major labels who showed interest.[11] Harper said the interest came from a friend of their booking agent, who in turn was friends with an A&R representative at Capitol. This person had seen the band live at six-to-seven of their gigs and won over others at the label. The band subsequently met with Capitol and two other labels, ultimately picking Capitol. Harper explained that Capitol were "just the coolest people. Their president, their vibe, and everything - they have a big catalogue" of acts such as the Beatles, Megadeth, and Pink Floyd.[9] Frontman Ryan Key also reasoned that listeners were unable to purchase One for the Kids in stores due to a lack of distribution and wanted a label that could rectify that.[12]

In June and July 2002, the band appeared on Warped Tour, which coincided with the release of the band's second EP The Underdog EP on July 2, through Fueled by Ramen.[13] Capitol Records had licensed the EP to Fueled by Ramen as not to lose the band punk credibility.[11] Two days after its release, bassist Warren Cooke left the band, citing personal reasons;[14] violinist Sean Mackin said there was in-fighting between them up to eight months before this occurred.[12] Cooke spot was temporarily filled by members of other acts on the tour, Home Grown and the Starting Line.[14] On July 21, 2002, Inspection 12 guitarist Peter Mosely joined Yellowcard as their bassist.[15] In October and November 2002, the band supported No Use for a Name on their headlining US tour,[16] and played a few shows with the Starting Line and Park.[17] In February 2003, Yellowcard played a handful of West Coast shows with Park and Stole Your Woman.[18]

Between signing to Capitol and recording, Yellowcard spent a period of time writing new material in several studios.[19] They spent around four months writing material, before going into pre-production. The band had one song, "Boxing Me", that their A&R person felt sounded like a single, but the members considered the track "too poppy" and dropped it.[9] Sessions for Ocean Avenue were held at Sunset Sound in Hollywood, California, in February and March 2003. Neal Avron produced and recorded the album with assistance from engineers Ryan Castle and Travis Huff.[20] Harper knew of Avron through his work with Everclear, New Found Glory, and the Wallflowers. He praised Avron for helping to achieve the "right kind of guitar tone, or master the violin, or help out with drum" sounds.[9] Tom Lord-Alge mixed the recordings at South Beach Studios in Miami Beach, Florida, with assistance from Femio Hernandez, before the album was mastered by Ted Jensen at Sterling Sound in New York City.[20]

Composition and lyrics

editThe sound of Ocean Avenue has been described musically as pop-punk[21][22][23] and punk rock,[24] and has drawn comparisons to Blink-182 and Simple Plan.[25] The album's title refers to a street in the band's hometown of Jacksonville, Florida, where they had they spent some of their childhood. Key typically comes up with a melody line and a chord progression, which he then shows to the rest of the band, who build upon it from this bare form.[11] Key and drummer Longineu W. Parsons III wrote together and would often jam material.[26] The band experimented with country and folk-stylized rock in songs like "Empty Apartment", "View from Heaven", and "One Year, Six Months".[27] When asked about a metal influence throughout the album, Key attributed this to Parsons, who was a metalhead.[26] Mosely played bass on every track, except for "Only One", which was done by Key. Mosely also played piano on "Empty Apartment" and "Only One", and added vocals. Christine Choi and Rodney Wirtz played cello and viola, respectively, on "Way Away", "Breathing", "Empty Apartment", "Only One", and "Believe"; Mackin and Avron wrote the string arrangement.[20]

The opening track "Way Away" is about a person leaving their home and finding their own way in life.[28] Key said he had had re-written the verse music, melody and lyrics 30 minutes prior to a show.[29] "Breathing" was a reaction to the end of Key's first post-high school relationship. He had written the guitar riff to it in a dressing room at the Glass House venue in Pomona, California while on a tour.[29] "Ocean Avenue" is anchored around a distorted staccato punk rock guitar riff;[30] in the song's lyrics, Key uses the person he is singing to as a metaphor for Jacksonville.[31] The song was inspired by Ocean Boulevard, a road in Jacksonville.[32] Key said the sign on that road lacked the word boulevard, only being named as such on a map. As he was trying to find a rhyme for the lyrics, he used the word avenue instead.[33] It was nearly left off the album as Key was unable to come up with a chorus that he was satisfied with, until settling on the lyric "Finding out things would get better". Discussing "Empty Apartment", he mentioned the various line-up changes the band had gone through, and "sometimes you're faced with a decision of: Do you quit? Do we break up and just call it? Or do we move on without this person?"[29] In "Life of a Salesman", Key talks about how he will act as a father by following his own father's example.[34] He said his relationship with his father was strained during the making of the album, and used the song as a way to remind him of his importance.[29]

"Only One" was written partway through the recording sessions, and Key said the lyrics were influenced by "a weird breakup". He explained it was "one of those where I felt like I had to do it, even though she didn't do anything wrong".[35] The music came about from Key using different amplifiers to achieve a different sound, utilizing a tremolo effect played through a Fender Twin amp. "Miles Apart" was written in the basement of The Nile venue in Phoenix, Arizona; Key thought the riff progression was very simplistic that he referred to it as "my first guitar riff dot com".[29] "Twentythree" is about growing up,[36] while the country-influenced song "View from Heaven",[37] with additional vocals from Alieka Wijnveldt,[20] discusses the death of a girlfriend.[34] Key explained that it was about a friend of his who had died of juvenile diabetes at age 18.[29] "Inside Out" is a mid-tempo rock track that is followed by "Believe", a homage to emergency service members who died in the September 11 attacks. In the context of the latter song, Key said that early on in their career, they would attract a fanbase from the tri-state area.[29] The penultimate track, "One Year, Six Months", is an acoustic ballad;[38] the band said they wanted something with a heavy amount of reverb as Sunset Sound had one of the earliest-built reverb chambers.[29] The album ends with "Back Home", which is about the things a person leaves behind in "Way Away".[28] Key had the clean intro and outro guitar riff for a period of time until it ended up in "Back Home".[29]

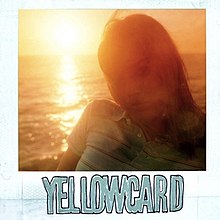

Release

editIn March 2003, Mosely left Yellowcard citing personal reasons and was replaced by Alex Lewis,[39] who was best friends with Harper and Mackin.[40] Following this, they went on tour with the Ataris; during the last night of the trek, Key had injured his jaw from messing around with Mackin. After seeing a doctor, Key stayed with his parents in Jacksonville[9] and had surgery. The rest of the band went on tour with Lagwagon while Peter Munters from Over It temporarily filled in for Key.[40] On May 4, 2003, Ocean Avenue was announced for release in two months' time.[41] Later that month, the band went on a brief tour of Japan, followed by headlining shows in California throughout June 2003. They took a week-long break before starting press and in-store in events in the lead up to the album's release.[9] Between mid-July and early August 2003, the group appeared on the Warped Tour,[42] and then toured with Don't Look Down.[43][44] Ocean Avenue was eventually released on July 22, 2003,[45] through Capitol Records after it was originally scheduled to be released on July 8.[41] The artwork features a blurry photo of a high school girl in front of a setting sun in California.[46] The model is Brittany Nash, who was photographed by Sasha Eisenman.[20] The album was released as an enhanced CD in some countries, which included a video entitled "The Making of Ocean Avenue" and a music video for The Underdog EP track "Powder".[47] The Japanese edition included "Firewater", "Hey Mike", and the acoustic versions of "Way Away" and "Avondale" as bonus tracks;[48] "Way Away" was released on radio the same day.[49] The CD version included "Hey Mike" and an acoustic version of "Avondale".[50] Key felt it was a "little more tough, a little more edgy" choice as the album's first single, wanting to avoid being seen as a poppy band.[11]

After Yellowcard finished performing on the Warped Tour in August, it went on a club tour in the US that was followed by a few radio show appearances.[51] The music video for "Way Away" premiered on The O.C. on September 2, 2003.[52] In October 2003, Yellowcard appeared at Shocktoberfest[53] and on IMX[54] before playing a handful of shows later that month.[55] In November, the band went on a US tour with Less Than Jake and Fall Out Boy,[56] and performed on Jimmy Kimmel Live![57] "Ocean Avenue" was released to radio on December 16, 2003.[49] They opened 2004 with a Canadian tour with Eve 6 and Jersey.[11] On March 3, 2004, the band appeared on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.[58] Around this time, Lewis was kicked out of the band and replaced by Mosely.[59] In March and April 2004, the band went on a co-headlined a US tour with Something Corporate, and was supported by Steriogram and the Format.[60] The band later toured Europe in May 2004 with Less Than Jake and the A.K.A.s.[61] On May 18, 2004, Yellowcard appeared on Late Night with Conan O'Brien.[62] "Way Away" was released as a single in the UK on May 31, 2004.[63]

In June 2004, "Only One" was released as a single;[64] the CD version included an AOL Session version of "View from Heaven" and a live version of "Miles Apart".[65] The music video for "Only One" was directed by Phil Harder and was filmed prior to the European tour.[35] According to Key, the video was "a love story that is surrounded by a lot of chaos and confusion".[64] After appearing at the main stage on Warped Tour, the band performed at the MTV Video Music Awards.[66] They played a few European shows with New Found Glory before embarking on tours in Australia and Japan.[67] "Ocean Avenue" was released as a single in the UK on September 6, 2004;[30] the CD version included "Firewater", an acoustic version of "Way Away", and the music video for "Ocean Avenue".[68] The video sees a woman steal something from Key, who then proceeds to chase her; he is in turn being chased by two villains, played by Mackin and Parsons.[11] Around this time, "Believe" was released as a single to honor the anniversary of the September 11 attacks.[69] In October and November 2004, the band went on a six-week tour of the US.[67]

Reissues and related releases

editIn November 2004, the live/video album Beyond Ocean Avenue: Live at the Electric Factory was released. It featured footage from a show earlier in the year, as well as a documentary on the history of the band.[70] Ocean Avenue was pressed on vinyl for the first time in 2011 through Hopeless Records, individually[71] and as part of the box set 2002–2011 Collection.[72] It was re-pressed by Hopeless Records in 2014,[73] and by Field Day Records in 2021.[74] In 2013, the band released an acoustic version of the album, Ocean Avenue Acoustic, in honor of the album's tenth anniversary.[75] The band toured the acoustic album later in 2013 and again in early 2014.[75][76] "Way Away", "Ocean Avenue", "Empty Apartment", "Life of a Salesman", "Only One", and "Believe" were included on the band's first compilation album Greatest Hits (2011).[77]

Critical reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [45] |

| Blender | [78] |

| Drowned in Sound | 2/10[79] |

| Entertainment Weekly | C[25] |

| Gigwise | [80] |

| IGN | 8.7/10[27] |

| laut.de | [46] |

| Now | 3/5[81] |

| The Spokesman-Review | B[82] |

| This Is Fake DIY | [24] |

Ocean Avenue received mixed reviews from music critics, many of which commented on the songwriting quality. Entertainment Weekly writer Joe Caramanica said the band laid "somewhere between A Simple Plan and blink-182, which is to say they're resilient enough not to whine, but too young to have a reason to anyhow".[25] He added that Key "wails every song without a hint of stylistic variation, subject matter be damned."[25] Elizabeth Bromstein of Now wrote that there was "a certain amount of drive" to the album, which offered "some neat guitar sounds as well as some nice arrangements".[81] IGN's Nick Madsen called the album a "solid and consistent record that has made a believer out of [him]".[27] PopMatters contributor Stephen Haag said the album "arrives at a time when pop punk's audience is maturing beyond the typical puerile fare that too many bands offer."[36] The staff at DIY said that the opening track could lead the listener to think of the album as "just another punk rock CD."[24] In spite of Mackin's violin giving the band some diversity from their peers, there was "still a fair share of bog standard punk rock, run of the mill stuff".[24] Drowned in Sound reviewer Nick Lancaster dismissed Yellowcard as "merely the latest band to hop off the boy-band-punk conveyor belt for their fifteen minutes of minor fame", though he wrote that it was "[n]ever actively bad, but offensive in its lack of imagination and drive".[79]

Reviewers were largely positive about the inclusion of Mackin's violin skills. The Spokesman-Review writer Cameron Adamson was initially sceptical of the use of violin, but "was pleasantly surprised"; as he listened to more of the album, he noted that the "energy that is felt from the start never dies".[82] AllMusic reviewer MacKenzie Wilson wrote that the album "delivers despite of its catchy recipe", with Mackin's "impressively skilled" violin playing that helped Yellowcard "in making something sound original and fresh".[45] Brad Maybe of CMJ New Music Report noted that the band set themselves apart with Mackin's violin; the album had "giant hooks and undeniably catchy choruses", which were "propelled to monstrous levels" by the violin.[37] Madsen wrote that as integral was Key's vocals and Harper's guitar were to the band, Mackin's violin was "more than just a gimmick and absolutely should not be written off as one".[27] Haag said the band with their violin parts "aren't entirely the answer to what is ailing pop punk, but they're not part of the problem either".[36]

Commercial performance and accolades

editOcean Avenue peaked at number 23 on the US Billboard 200,[83] and has sold 1.8 million copies in the US.[84] It also charted at number 8 in New Zealand,[85] and number 149 in the UK.[86] It reached number 52 on the year-end Billboard 200 for 2004.[87] The album was certified platinum in the US by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA),[88] gold in Canada by Music Canada,[89] and silver in the UK by the British Phonographic Industry (BPI).[90]

"Way Away" charted at number 25 on Alternative Airplay.[91] Outside of the US, it reached number 63 in the UK[92] and number 66 in Scotland.[93] "Ocean Avenue" charted at number 13 on Mainstream Top 40,[94] number 21 on Adult Top 40[95] and Alternative Airplay,[91] number 37 on Hot 100,[96] and number 38 on Radio Songs.[97] Outside of the US, the song charted at number 34 in New Zealand,[98] number 61 in Australia,[99] and number 65 in Scotland[100] and the UK.[92] It was certified double platinum by the RIAA[88] and silver by the BPI.[101] "Only One" charted at number 15 on Alternative Airplay,[91] number 22 on Bubbling Under Hot 100,[102] and number 28 on Mainstream Top 40.[94] It was certified gold in the US by the RIAA.[88]

The music video for "Ocean Avenue" was nominated for Best New Artist in a Video and MTV2 Award at the MTV Video Music Awards.[66] It has appeared on various best-of pop-punk album lists, being featured on lists by A.Side TV,[103] BuzzFeed,[22] Kerrang!,[104] Loudwire,[105] Rock Sound,[23] and Rolling Stone.[106] "Ocean Avenue" is featured on Billboard's list of the "100 Greatest Choruses of the 21st Century" and Cleveland.com's list of the top 100 pop-punk songs.[107][108] Alternative Press ranked "Ocean Avenue" at number 42 on their list of the best 100 singles from the 2000s.[109] Author Leslie Simon in her book Wish You Were Here: An Essential Guide to Your Favorite Music Scenes―from Punk to Indie and Everything in Between (2009) wrote that the album not only launched Key as an "unexpected emo sex symbol but proved that violins are actually more punk rock than you think".[110]

Track listing

editAll lyrics written by Ryan Key and Pete Mosely. All music performed by Yellowcard.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Way Away" | 3:22 |

| 2. | "Breathing" | 3:39 |

| 3. | "Ocean Avenue" | 3:18 |

| 4. | "Empty Apartment" | 3:37 |

| 5. | "Life of a Salesman" | 3:19 |

| 6. | "Only One" | 4:18 |

| 7. | "Miles Apart" | 3:32 |

| 8. | "Twentythree" | 3:28 |

| 9. | "View From Heaven" | 3:22 |

| 10. | "Inside Out" | 3:40 |

| 11. | "Believe" | 4:31 |

| 12. | "One Year, Six Months" | 3:29 |

| 13. | "Back Home" | 3:56 |

| Total length: | 47:26 | |

Personnel

editAdapted credits from the liner notes of Ocean Avenue.[20]

|

Yellowcard

Additional musicians

|

Production and design

|

Charts and certifications

edit

Weekly chartsedit

Year-end chartsedit

|

Certificationsedit

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

editCitations

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Pop-Punk Albums of All Time". Loudwire. November 9, 2023. p. 19. Yellowcard, 'Ocean Avenue' (2003).

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R.; Galil, Leor; Shteamer, Hank; Spanos, Brittany; Exposito, Suzy; Sherman, Maria; Grow, Kory; Epstein, Dan; Diamond, Jason; Viruet, Pilot (November 15, 2017). "50 Greatest Pop-Punk Albums". Rolling Stone. 38.

- ^ "The 51 greatest pop-punk albums of all time". September 23, 2017. p. 40. Yellowcard – Ocean Avenue (2004).

- ^ "Yellowcard!". Yellowcard. April 6, 2001. Archived from the original on April 6, 2001. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Paul, Aubin (February 23, 2001). "Listen to and Preorder new Yellowcard cd". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (July 21, 2001). "Yellowcard / Inspection 12 - Summer Tour". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ White, Adam (October 22, 2001). "Yellowcard / Bordem Tour". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Walter, David (June 27, 2003). "Yellowcard: Break from the Mold". Soundthesirens. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Yellowcard". Punk-It. May 5, 2003. Archived from the original on July 6, 2006. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ White, Adam (April 2, 2002). "Yellowcard Signs to Capitol Records". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Yellowcard - Ryan Key". ThePunkSite. January 19, 2004. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Hinrichs, Jennifer (February–March 2003). "Yellowcard Next Exit: Rock Star Land". In Your Ear Magazine. Archived from the original on January 13, 2005. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ White, Adam (June 24, 2002). "Yellowcard EP released / upcoming Warped Dates". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ a b White, Adam (July 4, 2002). "Bassist Warren Cooke leaves Yellowcard". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (July 21, 2002). "Yellowcard takes Inspection 12's bassist". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (September 27, 2002). "No Use For A Name to tour with Yellowcard, Eyeliners, Slick Shoes". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ White, Adam (October 19, 2002). "New Park song available". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (January 2, 2003). "Lobster tours: Over It, Park, Staring Back, and more". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Erwin, Ben (April 23, 2004). "Something Corporate, Yellowcard co-headline Sunday". The Daily Eastern News. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Ocean Avenue (booklet). Capitol Records. 2003. 7243 5 77360 2 2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ Brandon J. (March 23, 2018). "Everything Is Gonna Be Alright, Be Strong, Believe: 15 Hits From 15 Years Ago". Indie Vision Music. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Sherman, Maria; Broderick, Ryan (July 2, 2013). "36 Pop Punk Albums You Need To Hear Before You F----ing Die". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ a b Bird 2014, p. 69

- ^ a b c d "Yellowcard Ocean Avenue (EMI)". This Is Fake DIY. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Caramanica, Joe (July 25, 2003). "Ocean Avenue Review". Entertainment Weekly. p. 72. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Bussard, Lauren (November 26, 2003). "Yellowcard – Ocean Avenue – Interview". Lollipop Magazine. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Madsen, Nick (August 5, 2003). "Ocean Avenue". IGN. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Conlon, Chris (July 17, 2003). "Yellowcard album 'Way Away' cool". The Telegraph-Herald. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Reily, Emily (September 9, 2022). "Yellowcard's Ryan Key Breaks Down 'Ocean Avenue' Track by Track". Riot Fest. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Serck, Linda. "Yellowcard - Ocean Avenue (Parlophone)". musicOMH. Archived from the original on March 30, 2006. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ D'Angelo, Joe (April 6, 2004). "Yellowcard Get Homesick, Sing Of Spider-Man's Struggle". MTV. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Lakshmin, Deepa (September 27, 2016). "Ryan Key Revisits 'Ocean Avenue' Before Yellowcard's Breakup". MTV. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Gabby; Nicole (July 25, 2004). "Interviews/Ryan of Yellowcard 07/25/04". Concert Hype. Archived from the original on September 4, 2004. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Holz, Adam R; Smithouser, Bob. "Ocean Avenue". Plugged In. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b D'Angelo, Joe (May 7, 2004). "Warped Tour Main Stage Is A Long Time Coming For Yellowcard". MTV. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Haag, Stephen (December 4, 2003). "Yellowcard: Ocean Avenue". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Maybe 2003, p. 6

- ^ Sowing (October 1, 2010). "Review: Yellowcard - Ocean Avenue". Sputnikmusic. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Shari Black Velvet (August 2004). "A Day Away With Yellowcard". Black Velvet. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Kate. "Yellowcard". PunkRockReviews. Archived from the original on June 7, 2003. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Heisel, Scott (May 4, 2003). "Lobster newsbrief: Days Like These, Park, Yellowcard, more". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ "Final Band List Announced". Warped Tour. February 6, 2003. Archived from the original on October 3, 2003. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ White, Adam (July 14, 2003). "Don't Look Down's Summer Shows". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on September 19, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (August 23, 2003). "Don't Look Down's van stolen". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Wilson, MacKenzie. "Ocean Avenue - Yellowcard | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Yang, Xifan. "Ocean Avenue" (in German). laut.de. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Ocean Avenue (booklet). Capitol Records. 2003. CDP 7243 5 39844 0 3.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ Ocean Avenue (sleeve). Capitol Records. 2003. TOCP-66312.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ a b "FMQB Airplay Archive: Modern Rock". FMQB. Archived from the original on March 22, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ "Way Away" (sleeve). Capitol Records. 2004. 7243 5 48075 2 7.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ IGN Staff (August 4, 2003). "Yellowcard Tour Dates". IGN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (August 29, 2003). "Yellowcard rocks the OC". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on August 31, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ White, Adam (September 16, 2003). "Shocktoberfest In Pensacola This October". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (September 29, 2003). "Bands on TV - week of 9/29/03". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Moss, Corey (October 20, 2004). "Some Meatloaf, A Scoop Of Peas And Yellowcard?". MTV. Archived from the original on September 16, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ White, Adam (September 14, 2003). "Less Than Jake November Shows". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (November 17, 2003). "Bands on TV - week of 11/17/03". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (March 1, 2004). "Bands on TV - week of 3/1/04". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Loftus, Johnny. "Yellowcard | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (March 7, 2004). "Yellowcard/Something Corporate co-headlining tour". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ White, Adam (March 14, 2004). "Less Than Jake DVD, b-sides record, tour dates updates". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (May 17, 2004). "Bands on TV - week of 5/17/04". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Turner, Catherine. "Yellowcard - Way Away (Capitol)". musicOMH. Archived from the original on March 30, 2006. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Moss, Corey (June 21, 2004). "Yellowcard Are Ready To Unleash Their 'Chick Song'". MTV. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "Only One" (sleeve). Capitol Records. 2004. 7243 8 76604 27.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ a b IGN Staff (July 28, 2004). "Yellowcard Invades VMA's". IGN. Archived from the original on September 21, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ a b D'Angelo, Joe (August 27, 2004). "Yellowcard To Hit The Road Right After VMAs". MTV. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "Ocean Avenue" (sleeve). Capitol Records/Parlophone. 2004. 7243 5 48765 0 9/CDCLS 860.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ "Success of 'Ocean Avenue' has Yellowcard sailing". The Mount Airy News. August 28, 2004. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ MTV News Staff (September 20, 2004). "For The Record: Quick News On 'American Idol,' Metallica, Vanessa Carlton, Yellowcard, Mos Def, Television & More". MTV. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Ocean Avenue (sleeve). Hopeless Records. 2011. HR741-1.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ 2002–2011 Collection (sleeve). Hopeless Records. 2011. YEL0LEBSCL-DL00.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ Ocean Avenue (sleeve). Hopeless Records. 2014. HR741-1.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ Ocean Avenue (sleeve). Field Day Records. 2021. FDR-020.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ a b Campbell, Rachel (June 3, 2013). "Yellowcard announce 'Ocean Avenue' acoustic album, tour with Geoff Rickly (Thursday)". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on October 4, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Horansky, TJ (November 18, 2013). "Yellowcard announce more 'Ocean Avenue Acoustic' US tour dates with What's Eating Gilbert". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Greatest Hits (sleeve). Capitol Records. 2011. TOCP-71085.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) - ^ Eells, Josh. "Yellowcard Ocean Avenue". Blender. Archived from the original on August 8, 2004. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Lancaster, Nick (June 4, 2004). "Album Review: Yellowcard - Ocean Avenue". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on June 28, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Goodyear, Oliver. "Yellowcard, 'Ocean Avenue' (Capitol)". Gigwise. Archived from the original on December 23, 2004. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Bromstein, Elizabeth (January 29 – February 4, 2004). "Yellowcard Ocean Avenue (EMI)". Now. Archived from the original on February 20, 2005. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Adamson, Cameron (April 14, 2004). "Yellowcard's originality shines on 'Ocean Avenue'". The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "Yellowcard Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Caulfield, Keith (August 23, 2013). "Chart Moves: Washed Out, Valerie June Debut on Billboard 200, Wild Feathers Fly In at No. 1 on Heatseekers". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Yellowcard – Ocean Avenue". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Chart Log UK: "Ocean Avenue". UK Albums Chart. Zobbel.de. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2004". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Gold & Platinum". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Canadian album certifications – Yellowcard – Ocean Avenue". Music Canada. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "British album certifications – Yellowcard – Ocean Avenue". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Yellowcard Chart History (Alternative Airplay)". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Yellowcard | full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100 06 June 2004 - 12 June 2004". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Yellowcard Chart History (Mainstream Top 40)". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "Yellowcard Chart History (Adult Top 40)". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "Yellowcard Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "Yellowcard Chart History (Radio Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ "charts.nz - New Zealand charts portal". Charts.nz. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ "The ARIA Report: Week Commencing 28 June 2004" (PDF) (748). Australian Web Archive. July 7, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2004. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100 12 September 2004 - 18 September 2004". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- ^ "Yellowcard Ocean Avenue". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ "Yellowcard Chart History (Bubbling Under Hot 100)". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Rousseau, Rob (February 23, 2016). "The 13 best albums from the emo/pop-punk boom". A.Side TV. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ "The 51 greatest pop-punk albums of all time". Kerrang!. September 23, 2017. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Pop-Punk Albums of All Time — Ranked". Loudwire. January 28, 2020. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (November 15, 2017). "50 Greatest Pop-Punk Albums". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Zellner, Xander (April 24, 2017). "The 100 Greatest Choruses of the 21st Century". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Troy L. (March 2, 2022). "The 100 greatest pop punk songs of all time". Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Paul, Aubin (November 20, 2009). "At The Drive-In's 'One Armed Scissor' tops AP's 'Haircut 100' singles countdown". Punknews.org. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ Simon 2009, p. 101

- ^ "American album certifications – Yellowcard – Ocean Avenue". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

Sources

- Bird, Ryan, ed. (September 2014). "The 51 Most Essential Pop Punk Albums of All Time". Rock Sound (191). London: Freeway Press Inc.: 69. ISSN 1465-0185.

- Maybe, Brad (July 21, 2003). "Reviews". CMJ New Music Report. Vol. 76, no. 8. ISSN 0890-0795. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- Simon, Leslie (2009). Wish You Were Here: An Essential Guide to Your Favorite Music Scenes―from Punk to Indie and Everything in Between. New York City: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-157371-2.

External links

edit- Ocean Avenue at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)