Obeliscus Pamphilius is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was published in Rome by Ludovico Grignani[1] and dedicated to Pope Innocent X in his jubilee year.[2]: 16 The subject of the work was Kircher's attempt to translate the hieroglyphs on the sides of an obelisk erected in the Piazza Navona.[3]

The obelisk of Domitian

editThe obelisk was originally commissioned from Egypt by the emperor Domitian, probably for the Temple of Isis and Serapis.[4]: 200 The emperor Maxentius later had the obelisk moved outside the city walls to the Circus of Romulus on the Via Appia. There it fell into ruin, until Innocent X decided to have its broken parts brought to the Piazza Navona in front of his family's house, the Palazzo Pamphilj. He commissioned Kircher to lead the relocation and interpretation of the monument,[5] and Gian Lorenzo Bernini to design a fountain above which the obelisk was to be placed, known today as the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi.[6] At the time, nobody was aware of the connection between Domitian and the obelisk, and it was known as the 'Pamphilj obelisk' after the Pope's family name. It was only in 1827 that Champollion succeeded in translating the hieroglyphs, revealing that they included the names of Domitian, his father Vespasian and his brother Titus.[7]

Significance of the obelisk

editFor Kircher, obelisks and their hieroglyphic inscriptions were the source of hermetic wisdom that was older than, but continuous with Christian revelation. He believed that the Egyptians were the first to understand the underlying cosmic harmony of the universe, and that this was the basis of their religion and their philosophy. In making this argument Kircher drew on a long-established tradition of ancient texts from Herodotus, Plato, Diodorus, Plutarch and other authorities.[6][7][8] Kircher was convinced that the lost truths contained within the hieroglyphs represented what was described in the words of St Paul in the First Epistle to the Corinthians—"But we speak the wisdom of God in a mystery, even the hidden wisdom, which God ordained before the world unto our glory" (Corinthians 1, 2:7). Kircher believed that by translating the obelisk he would be unlocking the hidden wisdom imparted from God to the patriarchs long ago.[9]: 4

Translation

editAt the start of the project the obelisk was not intact; as well as the five major pieces there were numerous smaller pieces that were not immediately found. As part of his reconstruction, Kircher filled the missing gaps with the hieroglyphs he believed would best fit the text according to his understanding of their meaning. Later, the missing parts were found by archaeologist and brought together with the main body of the obelisk, and to everyone's amazement, the hieroglyphs on those parts were, according to Kircher himself, exactly as he had predicted. Cardinal Capponi, who was supervising the project, was so enthralled that he asked for it to be written up, and this was the origin of the work.[5]: 493–4 In fact Kircher's study had revealed that the same inscriptions were repeated on the different sides of the obelisk, so he was able to predict what would be found on parts he had not yet seen.[9]: 151

Kircher's approach to translation was to assume (incorrectly) that hieroglyphs were ideographs rather than representations of sound, and that they communicated ideas without grammar or syntax.[4]: 199 Kircher's self-described method of translation was first to make an accurate copy of each individual hieroglyphs, then think about suitable actions for each figure, and finally conclude the mystical meaning contained in each one of them.[9]: 5

We now know that images on the upper part of each side of the obelisk are iconic and do not have any textual meaning; the lower part contains a brief text about Domitian and Horus. On the south face of the obelisk the text reads "Horus, strong bull, beloved of Maat." This Kircher translated as:

'To the triform Divinity Hemptha - first Mind, motor of all things, second Mind, craftsman, pantamorphic Spirit - Triune Divinity, eternal, having no beginning or end, Origin of the secondary Gods, which, diffused out of the Monad as from a certain apex into the breadth of the mundane pyramid, confers its goodness first to the intellectual world of the Genies, who, under the Guardian Ruler of the Southern Choir and through swift, effective and resolute followers Genies who partake in no simple or material substance, communicate their participated virtue and power to the lower World...[4]: 200

Kircher's erroneous translations were carved in granite and fixed to the sides of the obelisk's pedestal, above Bernini's fountain, where they still stand today.[3]

Patronage

editKircher had dedicated Prodromus Coptus to his sponsor, Cardinal Francesco Barberini[3] and he had been very close to the Barberini Pope Urban VIII. The election of the Pamphilj Pope Innocent X represented a major shift in power and patronage systems. Cardinal Barberini had to flee into exile in France and Kircher needed to establish himself under the new regime.[10]: 53

One of Kircher's aims in publishing Obeliscus Pamphylius was to raise interest in his planned major work, Oedipus Aegyptiacus, and find sponsors for it. As he intended to be a large and lavishly illustrate work it would be expensive to produce. He secured funding from the Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III and Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany to produce Obeliscus Pamphylius and hoped that they would be interested in the larger project as well. It is also likely that Kircher was targeting his old friend Fabio Chigi, later Pope Alexander VII.[6]

This purpose of stimulating interest in the obelisk and securing funding explains the fact that the translation occupies only the last fifth of the work—the rest is taken up with dedications and with a history of the obelisk relayed by Kircher which we now know bears no relationship with reality. According to Kircher the monument had been commissioned by Pharaoh Sothis, son of Amenophis, who had restored Egypt to its original strength after the departure of Moses and the Israelites. It has been erected with three other obelisks near Thebes in around 1336 BC. In the second century AD Emperor Caracalla had brought it to Rome. Most of the rest of the work is an explanation of the significance of ancient Egyptian culture to the ancient Greek, Roman, and Hebrew civilisations, its influence on Islamic and rabbinical tradition.[6]

Censorship

editAll books intended for publication by Jesuit authors had to be approved by the order's own censors. In 1652 Nicolaus Wysing, who was one of the five Revisors General for Kircher's later work Oedipus Aegyptiacus, complained that Kircher had not complied with the requirements of the censors in respect of Obeliscus Pamphilius. Kircher had apparently added new material after the censors had completed their review, and reorganised the material they had already reviewed so as to make it difficult to see whether he had obeyed their instructions or not.[10]: 87

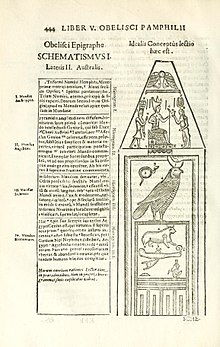

Illustrations

editIn addition to a number of woodcut illustrations, Obeliscus Pamphylius had six full-page plates.[2]: 50 The frontispiece, designed by Giovanni Angelo Canini and executed by Cornelis Bloemaert,[2]: 51 depicts Father Time with a scythe poised on the base of a toppled obelisk. The figure of Fame stands chained next to it, despondent, leaning on her arm, with her trumpet down. These figures represent the state of the obelisk before its discovery and interpretation by Kircher. In the centre of the image the god Hermes flies, in his role both as messenger of the classical gods, and the father of hermeneutics. He is explaining the meaning of the hieroglyphs on a scroll to a muse-like figure, who writes in a book bearing Kircher's name. She rests her elbow on a pile of volumes labelled Egyptian wisdom, Pythagorean mathematics and Chaldean astrology, implying that Kircher's work ranks with these and builds upon them. Beneath her foot is a cubic block carrying a symbol that combines a mason's square crossed with a curved trumpet and a staff with the head of a hoopoe. The square and trumpet were a misreading of the Egyptian crook and flail symbols. In front of her is a cherub representing Harpocrates, god of silence, who sits in the shade and holds the edge of the manuscript; the full meaning of the hieroglyphs is not to be revealed in Obeliscus Pamphylius, but in Kircher's long anticipated major work Oedipus Aegiptiacus. Harpocrates sits on a tiered pedestal inscribed in Hebrew, Samaritan, Coptic, Arabic and Ethiopian. At the bottom of the image, Harpocrates' foot tramples on the head of a crocodile representing Typhon.[2]: 28 Pierre Miotte created the illustrations of the obelisk, of the transport of obelisks by the ancients, and of "the ancient gods interpreted".[2]: 51

References

edit- ^ "Obeliscus Pamphilius". upenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Godwin, Joscelyn (2015). Athanasius Kircher's Theatre of the World. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-465-4.

- ^ a b c Rowland, Ingrid D. "Athanasius Kircher and the Egyptian Oedipus". uchicago.edu. University of Chicago. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Daniel Stolzenberg (April 2013). Egyptian Oedipus: Athanasius Kircher and the Secrets of Antiquity. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-92414-4. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ a b John Edward Fletcher (25 August 2011). A Study of the Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher, 'Germanus Incredibilis': With a Selection of His Unpublished Correspondence and an Annotated Translation of His Autobiography. BRILL. pp. 549–. ISBN 978-90-04-20712-7.

- ^ a b c d Rowland, Ingrid (2001). ""Th' United Sense of th' Universe": Athanasius Kircher in Piazza Navona". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 46: 153–181. doi:10.2307/4238784. JSTOR 4238784.

- ^ a b Parker, Grant (2003). "Narrating Monumentality: The Piazza Navona Obelisk". Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology. 16 (2): 193–215. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Anthony Grafton (1997). The Footnote: A Curious History. Harvard University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-674-30760-5. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Roberto Buonanno (31 January 2014). The Stars of Galileo Galilei and the Universal Knowledge of Athanasius Kircher. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-319-00300-9. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ a b Paula Findlen (2004). Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man who Knew Everything. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-94015-3.