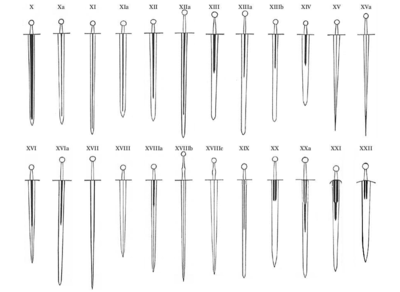

The Oakeshott typology is a way to define and catalogue the medieval sword based on physical form. It categorises the swords of the European Middle Ages (roughly 11th to 16th centuries[1]) into 13 main types, labelled X through XXII. The historian and illustrator Ewart Oakeshott introduced it in his 1960 treatise The Archaeology of Weapons: Arms and Armour from Prehistory to the Age of Chivalry.

The system is a continuation of Jan Petersen's typology of the Viking sword, which Petersen introduced in De Norske Vikingsverd ("The Norwegian Viking Swords") in 1919. In 1927, the system was simplified by R. E. M. Wheeler to only seven types, labelled I through VII. Oakeshott slightly expanded the system with two transitional types, VIII and IX, and then he started work on his own typology.

Among the many reasons for his typology, Oakeshott found date classification unreliable during his research. He wrote that the weapons' dates of manufacture, use, and retirement have been greatly obscured by trade, warfare, and other various exchanges combined with the weapons' own longevity.[1]

Criteria of definition

editOakeshott's 13 sword types are distinguished by several factors, the most important of which characterize its blade: cross section, length, fuller characteristics, and taper. Taper is the degree by which a blade's width narrows to its point. This varies from blades of constant taper, the edges of which are straight and narrow to a point, to blades devoid of taper, the edges of which are parallel and finish in a rounded point. A fuller is a groove that runs down the middle of a blade, designed to lighten the weapon.[2] Type X swords typically have a fuller running nearly its entire length, Type XXII blades have very short fullers, and Type XV blades have none at all.

Grip length can vary within a type (such as with #Type XIII).

Oakeshott's sword descriptions orient them with the point as the bottom and the hilt at the top. This was inspired by his observation that many blades bearing inscriptions and crests had to be oriented this way to be read correctly.[1]

Oakeshott types

editType X

editOakeshott X describes swords that were common in the late Viking age and remained in use until the 13th century. The blades of these swords are narrower and longer than the typical Viking sword, marking the transition to the knightly sword of the High Middle Ages.

This type exhibits a broad, flat blade, 80 centimetres (2.6 ft) long on average. A very wide and shallow fuller runs down each side of the blade, fading just before the point (which is rounded). The grip's length is consistent with earlier Viking swords, averaging about 9 centimetres (3.5 in). The cross-guard is about 18–20 centimetres (7.1–7.9 in) wide, is square in section, and it tapers towards the tips.[clarification needed] In some rare cases, the cross is slightly curved.[which?] The tang is usually very flat and broad, and it tapers sharply towards the pommel. 10th century Norsemen referred to this type of sword as gaddhjalt (or "spike hilt"), referring to the strong taper of the tang rather than some visible characteristic of the pommel.[citation needed] The pommel usually takes either an oval Brazil-nut form or a disc shape.

In 1981, Oakeshott introduced Subtype Xa to include swords of similar blades that have narrower fullers, originally classified under type XI.

Type XI

editSwords of this type were in use c. 1100 – c. 1175. It presents similarly to Type X, with a short grip and a fuller that nearly runs the blade's entire length. In comparison, however, the blade is distinctively longer and more slender, and it tapers to an acute point. The fuller is also narrower. The shape of type XI blades is more suitable for slashing from horseback. Though it tapers to a point, it is generally too flexible for effective thrusting.

Subtype XIa presents a broader, shorter blade.

Type XII

editTypical of the High Middle Ages, these swords begin to show greater tapering of the blade and a shortened fuller, features which improve thrusting capabilities while maintaining a good cut. The Cawood sword is an exceptionally well preserved type XII specimen, exemplifying a full-length taper and narrow fuller, which terminates 2/3 down the blade.[3] A large number of Medieval examples of this type survive. It certainly existed in the later 13th century, and perhaps considerably earlier, since the Swiss National Museum in Zürich possesses an example that has a Viking Age–type hilt but clearly a type XII blade.

The earliest known depiction of a type XII sword in art is in the statue of the Archangel Michael in Bamberg Cathedral, dating to c. 1200. The Maciejowski Bible (c. 1245) depicts other examples.

Subtype XIIa (originally classified as XIIIa) consists of the longer, more massive greatswords that appear in the mid–13th century, which precede the later long-swords and were probably designed to counter the improved mail armor of the time.

Single-handed transitional type XII swords have a grip about 4.5 inches (11 cm) in length.[4]

Type XIIa has a long grip similar to that of type XIIIa. The XIIa was originally a part of the XIIIa classification, but Oakeshott decided they "taper[ed] too strongly" and were "too acutely pointed" to fit appropriately.[5]

Type XIII

editThis typifies the classic knightly sword that developed during the age of the Crusades. Typically, examples date to the second half of the 13th century. Type XIII swords feature as a defining characteristic a long, wide blade with parallel edges, ending in a rounded or spatulate tip. The blade cross section has the shape of a lens. The grips, longer than in the earlier types, typically some 15 cm (almost 6 inches), allow occasional two-handed use. The cross-guards are usually straight, and the pommels Brazil-nut or disk-shaped (Oakeshott pommel types D, E, and I).

Subtype XIIIa features longer blades and grips. They correspond to the knightly greatswords, or Grans espées d'Allemagne, appearing frequently in 14th century German, but also in Spanish and English art. Early examples of the type appear in the 12th century, and it remained popular until the 15th century. Subtype XIIIb describes smaller single-handed swords of similar shape.

Very few examples of the parent type XIII exist, while more examples of the subtype XIIIa survive. A depiction of two-handed use appears in the Tenison (Alphonso) psalter. Another depiction of the type appears in the Apocalypse of St. John manuscript of c. 1300.

The "greatsword", within the context of the late medieval longsword, is a type of "outsize(d) specimen", specifically the type XIIIa. The weapons were referred to by a variety of names, as in grans espées d'Allemagne ("big swords of Germany").[6]

The larger subtype XIIIa sword has a grip approximately 6.5–9 in (17–23 cm) long.[7]

Type XIV

editEwart Oakeshott describes swords of Type XIV classification as

short, broad and sharply-pointed blade, tapering strongly from the hilt, of flat section (the point end of the blade may, in some examples, have a slight though perceptible mid-rib, with a fuller running about half, or a little over, of its length. This may be single and quite broad or multiple and narrow. The grip is generally short (average 3.75" or 9.5 cm) though some as long as 4.5" (11.4 cm); the tang is thick and parallel-sided, often with the fuller extending half-way up it (the tang). The pommel is always of "wheel" form, sometimes very wide and flat. The cross is generally rather long and curved (very rarely straight).

Eight of the nine examples Oakeshott provided of type XIV in Records of the Medieval Sword have the distinct blade profile of a very acute triangle, with only one specimen showing an accelerating taper toward the end of the blade.

Type XV

editStraight tapering blade with diamond cross-section and a sharp point. Type XVa have longer, narrower blades and grips sufficiently long for two-handed use. In contrast to type XIV, these are more greatly designed for thrusting above cleaving, their appearance coinciding with the rise of plate armor. However, blades of similar cross-section and profile can be found well before the Middle-Ages and after, meaning this blade form should not solely be assigned the purpose of defeating plate armor.[8] Many Type XV fall within the terminology of swords commonly called "bastard" or "hand-and-a-half swords" in reference to the longer grips that allowed both one and two handed use, though swords with grips of only around 5 inches would not be considered among these.[9]

Type XVI

editA flat cutting blade which steadily tapers to an acute point reinforced by a clearly defined ridge, making it equally effective for thrusting. This type somewhat resembles a more slender version of type XIV. These swords appear in the contemporary artwork of San Gimignano and many other works. Blade length of 70–80 cm (28–31 in). Sub-type XVIa have a longer blade with a shorter fuller (usually running down 1⁄3 and rarely exceeding 1⁄2 of the blade). The grip is often extended to accommodate one and a half or two hands.

Type XVII

editCharacterized by a long, evenly tapering blade, hexagonal cross section, two-handed grip. Stiff, and suited toward thrusting. Oakeshott found some to be heavy swords, some examples weighing more than 2 kg (4.4 lb), used for combat against armored opponents. Some of these blades however were light-weight, including a sword that Oakeshott studied at the Fitzwilliam museum of Cambridge. In use c. 1360–1420.[10]

Type XVIII

editTapering blades with broad base, short grip, diamond cross-section. In distinction from type XV, these blades almost always feature a raised mid-rib that reinforces the blade for thrusting, and in the examples given in Records of the Medieval Sword, they can be seen to have a less linear and consistent taper along the edge of the blade, sometimes showing a subtle increase of the taper toward the point.[11] Subtype XVIIIa: narrow blades with a longer grip. Subtype XVIIIb: Bastard swords with a longer blade and long grip; were in use c. 1450 – c. 1520. Subtype XVIIIc: shorter grip, broad blade of 90 cm (35 in). Subtype XVIIIe: Narrow, long blade with extended ricasso more narrow than the blade and very long grip.

Type XIX

edit15th century swords which were often one-handed, though two-handed examples exist. These have relatively narrow, flat blades of hexagonal cross-section, nearly parallel edges with little profile taper, narrow fullers, and a pronounced ricasso. The ricasso often presents increased blade decoration. Additionally, several blades of this type bear Arabic inscriptions as well as finger loops below the guard.[12]

Type XX

edit14th to 15th century "hand and a half sword" or "two-handed" swords, often with two or more fullers, sometimes reducing to one fuller partway down the blade. The edges of these blades are nearly parallel or only slightly tapered until reaching a final slope to a point. These are Bastard swords, and nearly always have a hand-and-a-half grip or Two-handed swords, with room for two hands. Subtype XXa: narrower blades with a more acute and linear taper, though these can still be distinguished in part by their multiple fullers.[13][14]

Type XXI

editBroad heavily tapering swords, similar to the fashionable Italian civilian Cinquedea of the late 15th century. Usually longer and less broad than the Cinquedea. Commonly presents with two or more fullers that continue nearly the full length of the blade. Also usually features downward (toward the blade) curved cross (quillions). The distinction away from a Cinquedea is largely based on size alone. A variation of the classic Cinquedea grip is not uncommon, though many have grips are more conventional to other European swords of the time period.[15]

Type XXII

editBroad flat blades, some sharing a moderate to heavy taper with Type XXII though not as heavily or consistently. These are often flat/spatulate in cross section with the exception of 1–2 narrow fullers that only extend a short distance beyond the handle. The proportions, history of surviving examples, and often ornate decoration indicate these may have mostly served a ceremonial role more than as weapons of war.[15] Mid 1400s–1500s.

References

edit- ^ a b c Ewart Oakeshott (1994). The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-85115-715-3. OCLC 807485557. OL 26840827M. Wikidata Q105271484.

- ^ Oakeshott, R. Ewart (1998) [First published 1960], The Archaeology of Weapons: Arms and Armour from Prehistory to the Age of Chivalry, Dover Publications, p. 98

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (1991), Records of the Medieval Sword, Boydell Press, p. 72

- ^ Ewart Oakeshott (1994). The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-85115-715-3. OCLC 807485557. OL 26840827M. Wikidata Q105271484.

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (1991), Records of the Medieval Sword, Boydell Press, p. 89

- ^ Ewart Oakeshott (1994). The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-85115-715-3. OCLC 807485557. OL 26840827M. Wikidata Q105271484.

- ^ Ewart Oakeshott (1994). The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-85115-715-3. OCLC 807485557. OL 26840827M. Wikidata Q105271484.

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (2015) [First published 1991], Records of the Medieval Sword, Boydell Press, p. 133

- ^ Ewart Oakeshott (1994). The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-85115-715-3. OCLC 807485557. OL 26840827M. Wikidata Q105271484.

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (2015) [First published 1991], Records of the Medieval Sword, Boydell Press, p. 162

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (2015) [First published 1991], Records of the Medieval Sword, Boydell Press, p. 176

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (2015) [First published 1991], Records of the Medieval Sword, Boydell Press, p. 202

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart (2015) [First published 1991], Records of the Medieval Sword, Boydell Press, p. 212

- ^ Arnow, Chad. "Spotlight: Oakeshott Type XX Swords". myArmoury.com. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ a b Arnow, Chad. "Spotlight: Oakeshott Type XXI and XXII Swords". myArmoury.com. Retrieved 15 September 2019.