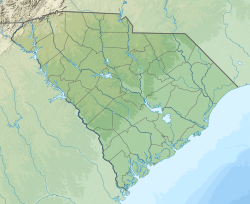

North Charleston is a city in Berkeley, Charleston, and Dorchester counties in the U.S. state of South Carolina.[1] As of the 2020 census, North Charleston had a population of 114,852,[4] making it the third-most populous city in the state, and the 248th-most populous city in the United States. North Charleston is a principal city within the Charleston-North Charleston, SC Metropolitan Statistical Area, which had an estimated population of 849,417 in 2023.[5]

North Charleston | |

|---|---|

North Charleston City Hall | |

| Motto(s): "A great place to live, work, and play" "Perseverance – Progress – Prosperity" | |

Interactive map of North Charleston | |

| Coordinates: 32°53′7″N 80°1′1″W / 32.88528°N 80.01694°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | South Carolina |

| Counties | Berkeley, Charleston, Dorchester[1] |

| Incorporated | June 12, 1972 |

| Named for | Being north of Charleston |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Reginald L. “Reggie” Burgess |

| Area | |

• City | 81.06 sq mi (209.95 km2) |

| • Land | 77.63 sq mi (201.06 km2) |

| • Water | 3.43 sq mi (8.89 km2) 4.23% |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 114,852 |

• Estimate (2023)[4] | 121,469 |

| • Rank | 248th in the United States 3rd in South Carolina |

| • Density | 1,527.8/sq mi (589.9/km2) |

| • Urban | 684,773 (US: 63rd) |

| • Metro | 849,417 (US: 71st) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 29405, 29406, 29410, 29415, 29418, 29419, 29420, 29423 |

| Area code(s) | 843, 854 |

| FIPS code | 45-50875 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1225072[3] |

| Sales tax | 9.0%[6] |

| Website | www |

History

edit1680–1901: Plantations

editFrom the 17th century until the Civil War, plantations cultivated commodity crops, such as rice and indigo. Some of the plantations in what is now North Charleston were:

- Archdale Hall Plantation – dating from 1680, Archdale Hall was on the Ashley River. By 1783, it had grown to almost 3,000 acres (12 km2). Its primary crops were indigo and rice. The plantation was the longest family-owned plantation in South Carolina. It has since been redeveloped into the Archdale subdivision. (Archdale subdivision is not in corporate city limits of, but is surrounded by North Charleston)

- Camp Plantation – dating from 1705, Camp Plantation covered around 1,000 acres (4.0 km2).

- Elms Plantation – dating from 1682, Elms Plantation was founded by Ralph Izard. Its principal crop was rice. It covered nearly 4,350 acres (17.6 km2), stretching across parts of what are now the cities of Goose Creek and North Charleston. Charleston Southern University is on part of the original plantation lands.

- French Botanical Garden – established between 1786 and 1796, this small plantation/garden area of 111 acres (0.45 km2) was owned and maintained by the French botanist André Michaux. It was closed by Michaux's son in 1803. The garden was near what is today the Charleston International Airport, and the parkway connecting Dorchester Road with International Boulevard is named in his honor.

- Marshlands, Mons Repos and Retreat plantations – the Retreat Plantation dates from 1672 and the Marshlands Plantation dates from 1682. Mons Repos was developed around 1798. The land from all three plantations was acquired by the federal government for development of the Charleston Naval Base and Charleston Naval Shipyard. The Marshlands Plantation's main house has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. To preserve the house, it was moved in 1961 to land at Fort Johnson on James Island and is currently used as offices for the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources.[7]

- Oak Grove Plantation – dating from 1680, Oak Grove originally covered 960 acres (3.9 km2) along the Cooper River. By 1750, its owners had expanded the plantation to about 1,127 acres (4.56 km2).

- Tranquil Hill Plantation – started in 1683, Tranquil Hill was originally known as White Hall Plantation, a name it kept until 1773. Its principal crop was rice. It encompassed about 526 acres (2.13 km2). In the late 20th century, it was redeveloped as the Whitehall residential subdivision.[8]

- Windsor Hill Plantation – established in 1701, Windsor Hill was an inland rice plantation that covered nearly 1,348 acres (5.46 km2); parts of the cities of Goose Creek and North Charleston now occupy some of this area.[9] General William Moultrie, victor at the Battle of Sullivan's Island in 1776 and governor from 1785 to 1787 and 1792–94, was originally buried here. His remains were exhumed and reburied at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island in 1977.[10] The Windsor Hill Plantation subdivision was developed on a portion of the eponymous plantation's property.

The large plantations were subdivided into smaller farms in the late 19th century as the urban population began moving northward. Due to the large labor forces of enslaved African Americans who worked these properties for over two centuries, the population of Charleston County in 1870 was 73 percent black; they were freedmen by this time. After the Civil War, phosphate fertilizer plants were developed, with extensive strip mining between the Ashley River and Broad Path (Meeting Street Road). The main route for transportation of these phosphates eventually became known as Ashley Phosphate Road.

1901–1972: Incorporation

editSince the early 20th century, the section of unincorporated Charleston County that later became North Charleston had been designated by Charleston business and community leaders as a place for the development of industry, military and other business sites. The first industry started in this area was the E.P. Burton Lumber Company. In 1901, the Charleston Naval Shipyard was established with agreements between the federal government and local Charleston city leaders. Shortly thereafter, the General Asbestos and Rubber Company (GARCO) built the world's largest asbestos mill under one roof.

In 1912, a group of businessmen from Charleston formed a development company that bought the E.P. Burton Lumber Company tract and began to lay out an area for further development. The Park Circle area was one of the first to be designed and developed, allocating sections for industrial, commercial, and residential usage. Park Circle was planned as one of only two English Garden Style communities in the US, and most of the original planning concept remains today. Some of the streets in the area still bear the names of these original developers: Durant, Buist, Mixon, Hyde, and O'Hear. During World War II, substantial development occurred as the military bases and industries expanded, increasing the personnel assigned there. New residents moved to the region to be closer to their work.

From World War II through the 1960s, many whites who lived in this region (referred to by Charlestonians as the North Area) were unhappy about the way parts of their community were being developed. They wanted the citizens in the area to have direct control over future development. African Americans were still excluded from the political system due to the state's 1895 disfranchising constitution. Many white Democrats' attempts to create an independent city were defeated via court rulings.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave the federal government the means to enforce citizens' constitutional rights, and African Americans in South Carolina gradually reclaimed their franchise. As a means of bringing the government closer to the people, an incorporation referendum was held on April 27, 1971. On June 12, 1972, after a series of legal battles, the South Carolina Supreme Court upheld the referendum results. North Charleston became a city and elected John E. Bourne Jr. as its first mayor.

1972–1982: First decade

editWhen North Charleston was incorporated on June 12, 1972, it consisted of several areas, including the Russelldale, Ferndale, Morningside, Liberty Park, Palmetto Heights, Singing Pines, Dewey Hill, Liberty Homes and John C. Calhoun Homes neighborhoods. Within the first week of operation, the city passed a 61-page Code and signed a five-year lease for 308 Montague Avenue for $300.00 per month. Also during June, the city hired a police chief, and treasurer and annexed its first industry, which was Textone Incorporated Plywood, Westvaco. On June 21, a ribbon was cut on the first city park on Virginia Avenue. At the end of the first month, the city officials reached an agreement for garbage collection and fire protection by the local public service district. The month concluded with the city's first big annexation, south of Bexley Street between Spruill Avenue and the Charleston Naval Shipyard. By December, North Charleston had become the fourth-largest city in the state after annexing the Naval Base, the Air Force Base and the Charleston International Airport.[11]

In February 1973, North Charleston doubled its area through annexation, and in March expanded into Berkeley County. In May 1973, the city launched its new police department, which included 21 officers and six cars. By the end of North Charleston's first year, the population had increased from 22,000 to 53,000, largely through annexation. Through continued growth and the development of 20 churches, a 62-store shopping mall and other large tracts of residential neighborhoods, the city was ranked as the third-largest city in South Carolina on July 3, 1976.

On June 12, 1982, North Charleston had a population of 65,000 in a 30.5-square-mile (79 km2) area. In ten years, the city's growth rate was 250 percent. It had made $15 million in capital investments; $1.95 million invested in parks and recreation facilities, and $2.28 million in economic development.

1982–1996

editIn 1983, North Charleston became the first city in South Carolina to implement a computer-aided dispatch system. Baker Hospital opened a new facility on the banks of the Ashley River. Plans were revealed in 1985 for the 400-acre (1.6 km2) Centre Pointe retail development.

By 1986, North Charleston's population had reached 78,000, spanning 47 square miles (120 km2). A monument to honor Vietnam veterans was erected and dedicated in front of City Hall, where it stood for over 20 years before being moved to Patriots Point in 2008. The city celebrated its 15th anniversary the next year, marked by such events as the opening of the Northwoods Center shopping complex and the development of a beach in the middle of the city with the opening of Treasure Lake.

In September 1989, Hurricane Hugo devastated the area, causing a total of over $2.8 billion in damage to the South Carolina Lowcountry.

In 1991, John E. Bourne, Jr., lost his bid for a sixth term as mayor to Bobby Kinard, who became the city's second mayor. Kinard's tenure as mayor was tumultuous and was marked by repeated conflict with the City Council; its members stripped Kinard of his mayoral powers during a council meeting. Kinard resigned in 1994 on the grounds that his relationship with the council was damaged irreparably.[12] R. Keith Summey was elected the city's third mayor to fill the vacant seat. Kinard returned to his law practice. In 2023, former North Charleston Police Chief Reggie Burgess was elected mayor, the first Black person to serve in the role.[13]

In 1993 a squadron of C-17 Globemaster III aircraft was established at Charleston Air Force Base, bringing more residents and jobs. The North Charleston Coliseum opened, and the South Carolina Stingrays of the ECHL began play later that year.

1996–present: redevelopment

editThe Charleston Naval Base ranked as the largest employer of civilians in South Carolina into the 1990s. The influence of Lowcountry legislators and the threat of nuclear attack played an important role in keeping North Charleston's bases open in the face of periodic attempts at closure.

In the early 1990s, with the resolution of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union, plus impending defense budget cuts, the Charleston Navy Base was proposed for closure. In 1993, the Charleston Naval Base was given a closure date of April 1, 1996. Given its annual expenditures of approximately 1.4 billion dollars in the region, the base's closing represented a major loss of jobs and a blow to the entire Tri-County economy. Over the years, billions of federal dollars had flowed into the region's economy and hundreds of thousands of jobs were filled by military and civilian personnel,[14] the vast majority civilians. Many military personnel who worked at or passed through the base returned to the city to retire. After the Charleston Naval Base and Charleston Naval Shipyard closed, parts of the base and dry docks were leased to various government and private businesses. Community parks for North Charleston were established on old base grounds, including Riverfront Park.

After years of development, community input and revisions, the Noisette Community Master Plan for the old naval base was finalized in a contractual agreement in early 2004. The plan sought to preserve historic architectural styles, neighborhood diversity, and the area's unique social fabric. It is also intended to restore environmental stability and beauty, attract jobs, improve services such as education and health care, reduce dependence on car travel, promote recreation, eliminate the foundations of crime and poverty, and strengthen residents' sense of pride.

In 2005, city officials discovered that Noisette had borrowed $3 million against the land on the former base without their knowledge. The next year, Noisette borrowed $23.7 million from Capmark Investing Group, using most of its remaining land on the base as collateral. Noisette failed to make timely repayment to Capmark, and the property went into foreclosure. Noisette representatives insisted at the time that they would be able to repay Capmark and make good on their vision for redeveloping the old Navy base.[15]

In July 2014, the City of North Charleston and Chicora Garden Holdings, LLC announced the planned redevelopment of the old Naval Hospital property, to be known as the Chicora Life Center.[16] As part of that announcement, Chicora Garden Holdings announced an initial $3 million investment in the project. The City of North Charleston announced that the Chicora Life Center "will feature myriad social, government, non-profit and care facilities—all in one building conveniently located in the heart of Charleston County."

On October 7, 2014, Palmetto Business Daily reported that UC Funds was funding $13.9 million in loans to the Chicora Life Center for completion of the project.[17] That newspaper also reported that Bennett Hofford Construction Company also completed Phase 1 of a new Heating, Ventilation and Air Condition (HVAC) for the portion of the building leased by the County of Charleston.[18]

Discussion between city and state officials regarding the industrial development of the remaining portions of the former base stalled in 2009, primarily due to a dispute over rail access to a proposed intermodal terminal to occupy the central portion of the area. Representatives of the state government sought to have rail access from both the north and south. This notion was contradicted by Mayor Summey, who insisted that the northern rail access be abandoned to avoid heavy rail traffic through the slowly revitalizing Park Circle neighborhood.[15]

In October 2009, Boeing announced the selection of North Charleston for its new 787 Dreamliner aircraft assembly and delivery prep center. This positioned North Charleston as one of the major aircraft centers of the world, with the potential for thousands of new jobs to provide quality work for residents of the city and the entire Tri-County area.[19]

In December 2010, a Delaware corporation with ties to former state Commerce Secretary Bob Faith bought the largest parcel (approximately 240 acres (0.97 km2) at the north end of the former base) of Noisette land.[20] The corporation transferred the deed for that land to the state's Commerce Department's Public Railways Division, which had the impetus to move forward with their proposed railyard with northern and southern access despite Summey's objections. Summey announced his intent to sue the state Commerce Department on the grounds that its plan violated the city's agreement with the State Ports Authority that no rail be run through the north end of the former base.[21]

On April 4, 2015, a shooting incident took place, in which Walter L. Scott, who was driving a car with a suspected broken taillight in North Charleston, was fatally shot after being stopped by Officer Michael T. Slager. A video by a bystander was broadcast nationally. Slager was charged with murder.[22][23] A mistrial was declared on December 5, 2016. The second trial in state court and separate federal charges are still pending.[24]

Geography

editNorth Charleston is near the Atlantic Ocean in the coastal plain just north of Charleston in South Carolina. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 81.06 square miles (209.9 km2), of which 77.63 square miles (201.1 km2) is land and 3.43 square miles (8.9 km2) (4.23%) is water.[2]

The city is bordered by Charleston to the south and east, the city of Hanahan to the north and east, the city of Goose Creek to the northeast, the unincorporated suburb of Ladson to the north, and the town of Summerville to the northwest. The Ashley River forms a large part of the southwest border of the city, and the Cooper River forms the southeastern border.

Climate

edit| Climate data for Charleston Int'l, South Carolina (1981–2010 normals,[25] extremes 1938–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

99 (37) |

94 (34) |

88 (31) |

83 (28) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 75.3 (24.1) |

78.1 (25.6) |

83.5 (28.6) |

88.5 (31.4) |

92.7 (33.7) |

96.8 (36.0) |

98.0 (36.7) |

96.5 (35.8) |

92.6 (33.7) |

87.1 (30.6) |

81.9 (27.7) |

76.8 (24.9) |

99.2 (37.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.0 (15.0) |

62.8 (17.1) |

69.6 (20.9) |

76.4 (24.7) |

83.2 (28.4) |

88.4 (31.3) |

91.1 (32.8) |

89.5 (31.9) |

84.8 (29.3) |

77.1 (25.1) |

69.8 (21.0) |

61.6 (16.4) |

76.2 (24.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 37.5 (3.1) |

40.6 (4.8) |

46.7 (8.2) |

53.3 (11.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

69.6 (20.9) |

73.0 (22.8) |

72.3 (22.4) |

67.2 (19.6) |

56.8 (13.8) |

47.5 (8.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

55.6 (13.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 21.4 (−5.9) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

38.6 (3.7) |

49.5 (9.7) |

61.1 (16.2) |

67.5 (19.7) |

66.0 (18.9) |

55.6 (13.1) |

41.0 (5.0) |

32.6 (0.3) |

24.0 (−4.4) |

18.8 (−7.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 6 (−14) |

12 (−11) |

15 (−9) |

29 (−2) |

36 (2) |

50 (10) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

42 (6) |

27 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

8 (−13) |

6 (−14) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.71 (94) |

2.96 (75) |

3.71 (94) |

2.91 (74) |

3.02 (77) |

5.65 (144) |

6.53 (166) |

7.15 (182) |

6.10 (155) |

3.75 (95) |

2.43 (62) |

3.11 (79) |

51.03 (1,296) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | trace | 0.2 (0.51) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.5 (1.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.6 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 11.9 | 13.0 | 13.2 | 10.0 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 112.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.8 | 67.4 | 68.1 | 67.5 | 72.5 | 75.1 | 76.6 | 78.9 | 78.2 | 74.1 | 72.7 | 71.6 | 72.7 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 36.0 (2.2) |

37.4 (3.0) |

44.8 (7.1) |

51.3 (10.7) |

61.0 (16.1) |

67.8 (19.9) |

71.4 (21.9) |

71.4 (21.9) |

66.9 (19.4) |

55.9 (13.3) |

47.5 (8.6) |

39.9 (4.4) |

54.3 (12.4) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.3 | 186.7 | 243.9 | 275.1 | 294.8 | 279.5 | 287.8 | 256.7 | 219.7 | 224.5 | 189.5 | 171.3 | 2,808.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 56 | 61 | 66 | 71 | 69 | 65 | 66 | 62 | 59 | 64 | 60 | 55 | 63 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[26][27][28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 62,479 | — | |

| 1990 | 70,218 | 12.4% | |

| 2000 | 79,641 | 13.4% | |

| 2010 | 97,471 | 22.4% | |

| 2020 | 114,852 | 17.8% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 121,469 | [4] | 5.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29] 2020[4] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[30] | Pop 2010[31] | Pop 2020[32] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 34,443 | 36,945 | 43,506 | 43.25% | 37.90% | 37.88% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 39,096 | 45,507 | 46,174 | 49.09% | 46.69% | 40.20% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 290 | 333 | 355 | 0.36% | 0.34% | 0.31% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 1,245 | 1,871 | 3,353 | 1.56% | 1.92% | 2.92% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 54 | 119 | 138 | 0.07% | 0.12% | 0.12% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 116 | 226 | 641 | 0.15% | 0.23% | 0.56% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,234 | 1,853 | 4,615 | 1.55% | 1.90% | 4.02% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 3,163 | 10,617 | 16,070 | 3.97% | 10.89% | 13.99% |

| Total | 79,641 | 97,471 | 114,852 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 114,852 people, 47,066 households, and 24,660 families residing in the city.

2010 census

editAt the 2010 census, there were 97,471 people, 35,316 households, and 23,271 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,360.6 inhabitants per square mile (525.3/km2). There were 42,219 housing units at an average density of 574.5 per square mile (221.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 37.90% Non-Hispanic White, 46.69% Non-Hispanic African American, 0.34% Native American, 1.92% Asian, 0.12% Pacific Islander, 0.23% from other races, 1.90% from two or more races, and 10.89% Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 34,012 households, out of which 37.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.0% were married couples living together, 22.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.3% were non-families. 28.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.51 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.9% under the age of 18, 13.4% from 18 to 24, 32.0% from 25 to 44, 17.7% from 45 to 64, and 9.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $36,719, and the median income for a family was $34,621. Males had a median income of $30,620 versus $28,248 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,361. About 19.9% of families and 23.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.8% of those under age 18 and 13.0% of those aged 65 or over.

Economy

editWith the arrival of Boeing Aircraft, the city is one of only three places in the world for the manufacture and assembly of wide-body long-range commercial aircraft; the other two places are in and around Everett, Washington (Boeing); Toulouse, France (Airbus).

North Charleston is the home to the Global Financial Services – Charleston (a section of the U.S. State Department), at the old Naval Station. Global Financial Services – Charleston is responsible overall for more than 200 bank accounts in over 160 countries and 169 different currencies. In 2005, it disbursed over $10 billion and purchased over $3 billion in foreign currency. As part of an initiative by the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide mail-order prescriptions to veterans using computerization, at strategic locations, North Charleston is also the location of a Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy (CMOP).

Major businesses in the area include:

- Boeing – adjacent to the Charleston International Airport, Boeing has set up an East Coast facility in North Charleston for manufacturing fuselage components, assembling, and flight testing Boeing 787 aircraft, ready for delivery to airlines.[33]

- Cummins Turbo Technologies – Corporate center and manufacturing plant (truck engine parts). Located on Palmetto Commerce Parkway.[34]

- DXC Technology – Branch offices – IT/business services company.

- Hess Corporation – port facilities for tanker ships, serving the entire Tri-County Metro area Hess gas stations. Located off Virginia Avenue.

- InterContinental Hotels Group – Call center of parent company for Holiday Inn hotels, employing more than 400 people. Located on Ashley Phosphate Road.[35]

- iQor – Call center providing outsourced customer service, retention, and revenue recovery services to large and mid-sized companies. Employs 360 workers. Located on Dorchester Road.[36]

- Kapstone – Kraft paper mills employing 1,100 workers. Located on the Cooper River.[37]

- Mercedes-Benz Group – Plant for manufacturing Mercedes Vans, employing 200 people. Located on Palmetto Commerce Parkway.[38]

- Robert Bosch GmbH – Manufacturer of automotive drive train components, to include gasoline and diesel fuel injectors and electronic stability control systems. On Dorchester Road (note: Robert Bosch is not in corporate city limits of, but is surrounded by, North Charleston)[39]

- Venture Aerobearings – Plant manufactures bearings for jet engines. On Palmetto Commerce Parkway.[40]

As of 2016, North Charleston had the highest rate of eviction filings and judgments of any American city with a population of 100,000 or more (in states where complete data was available).[41]

The National Weather Service Office in Charleston is also located in North Charleston adjacent to the airport, serving Southeastern South Carolina and Southeastern Georgia including Savannah, but the radar it operates is located in Beaufort County.[42]

Military presence

editNorth Charleston, Goose Creek, and Hanahan are home to branches of the United States Military.[43][44] During the Cold War, the Naval Base (1902–1996) became the third largest U.S. homeport serving over 80 ships and submarines. The Charleston Naval Shipyard repaired frigates, destroyers, cruisers, sub tenders, and submarines. The Shipyard was also equipped for the refueling of nuclear subs.[45][46]

During this period, the Weapons Station was the Atlantic Fleet's load out base for all nuclear ballistic missile submarines.[47] Two SSBN "Boomer" squadrons and a sub tender were homeported at the Weapons Station, while one SSN attack squadron, Submarine Squadron 4, and a sub tender were homeported at the Naval Base.[46] At the 1996 closure of the Station's Polaris Missile Facility Atlantic (POMFLANT), hundreds of nuclear warheads and their UGM-27 Polaris, UGM-73 Poseidon, and UGM-96 Trident I delivery missiles (SLBM) were stored and maintained, guarded by a U.S. Marine Corps Security Force Company.[48][49][50][51]

In 2010, the Air Force Base (3,877 acres (1,569 ha)) and Naval Weapons Station (16,274 acres (6,586 ha)) merged to form Joint Base Charleston.[52][49] Today, Joint Base Charleston, encompassing about 24,000 acres in Charleston and Berkeley counties; supports 53 Military Commands and Federal Agencies, providing service to over 79,000 Airmen, Sailors, Soldiers, Marines, Coast Guardsmen, DOD civilians, dependents, and retirees.[53][54][55]

In supporting Joint Base Charleston, 231 acres (93 ha) of the former Charleston Naval Base have been transformed into a multiuse Federal complex, with 17 Government and Military tenants, as well as homeport for six RO-RO Military Sealift Command ships, two Coast Guard National Security Cutters, two NOAA research ships, Coast Guard Maritime Law Enforcement Academy, and the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers.[56][45][57]

Arts and culture

editMuseums, historical sites, and other attractions include:

- The H.L. Hunley Museum is located at the old Naval Base in North Charleston. The Civil War-era submarine, recovered from the ocean floor August 8, 2000, is undergoing restoration and examination. The Hunley bears the distinction of being the first successful combat submarine in the world.

- The Greater Charleston Naval Memorial is located at Riverfront Park on the old Navy Yard. It features sculptures of the different types of ships built and serviced at the Charleston Naval Shipyard, and also features full-size replicas of the Lone Sailor and Homecoming sculptures.

- The North Charleston and American LaFrance Fire Museum and Educational Center is located between Tanger Outlet Mall and the North Charleston Coliseum. The museum is filled with one-of-a-kind and antique vehicles and fire equipment (some from as early as the mid 18th century) and utilizes multiple interactive displays.

From its establishment in August 1999, the Convention Center has attracted millions of guests and visitors to North Charleston and contributed significantly to the local and regional economy. The complex includes exhibition halls, ballrooms and meeting rooms.[58] The Performing Arts Center, the North Charleston Coliseum, and the Charleston Area Convention Center are owned by the City of North Charleston and managed by SMG. Together with the co-located Embassy Suites hotel, they help create an entertainment and cultural complex that serves the City of North Charleston and the entire region:

- The North Charleston Coliseum is located near the Charleston International Airport. The coliseum is one of the largest venues in South Carolina, with 13,295 seats. The coliseum also hosts many special events, concerts, and local graduations. The coliseum is home to the South Carolina Stingrays hockey team of the ECHL.[59]

- The North Charleston Performing Arts Center seats up to 2,341 and hosts major Broadway shows as well as national and world-renowned musical and theatrical performers.[60]

The Jenkins Orphanage (now Jenkins Institute For Children) left Charleston in 1937 and moved to 3923 Azalea Drive in what is now North Charleston. The institute is known for its contributions to child welfare in the area and the Jenkins Orphanage Band.[61][62][63]

The Park Circle Film Society[64] is a nonprofit art house theater that holds over 70 screenings of independent and documentary films each year. It holds the annual Lowcountry Indie Shorts Festival, South Carolina's festival dedicated to short film.

Parks and recreation

edit- Danny Jones Complex

- Ingevity-Kapstone Park

- Northwoods Park

- Park South

- Park Circle

- Quarterman Park

- Ralph M. Hendricks Park

- Riverfront Park

- Wannamaker County Park

- Wescott Park

Sports

editThe South Carolina Stingrays are the first professional ice hockey team established in South Carolina. They have been a member franchise of the ECHL since their inception in 1993 and have been affiliated with the Boston Bruins of the National Hockey League since 2012, following the end of an eight-year affiliation with the Washington Capitals. The Stingrays play their home games at the North Charleston Coliseum.

Government

editThe city is run by an elected Mayor–council government system, with the mayor acting as the chief administrator and the executive officer of the municipality. The mayor also presides over city council meetings and has a vote, the same as the other ten council members. The mayor is elected at-large and the council members from ten single-member districts.[65]

City government offices moved into a new, more centrally located city hall in 2009.[66]

Mayor

edit- Current mayor

- Reginald L. “Reggie” Burgess

- Previous mayors

- R. Keith Summey (1994–2023)

- Kenneth McClure (1977–2022) – Interim mayor, 1994

- W. Robert Kinard (1946–2010) – Second mayor, served from 1991 to 1994

- John E. Bourne Jr. (1927–2018) – First mayor, served from 1972 until 1991[67]

Crime

edit| North Charleston | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2022) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 27.8 |

| Rape | 70.0 |

| Robbery | 193.1 |

| Aggravated assault | 668.6 |

| Total violent crime | 959.5 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 479.7 |

| Larceny-theft | 3,794.0 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 591.0 |

| Arson | 20.2 |

| Total property crime | 4,885.0 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. 2022 population: 118,608 Source: 2022 FBI UCR Data | |

The following table shows North Charleston's crime rate for calendar year 2020 in six crimes that Morgan Quitno uses for their calculation for "America's most dangerous cities" ranking, in comparison to the national average. The statistics provided are for a crime rate based on the number of crimes committed per 100,000 people.

| Crime (2020) | Per 100,000 | Total Number |

|---|---|---|

| Murder | 32.3 | 38 |

| Rape | 76.6 | 90 |

| Robbery | 270.6 | 318 |

| Assault | 765.1 | 899 |

| Burglary | 554.0 | 651 |

| Theft | 3,972 | 4,667 |

| Auto thefts | 578.7 | 680 |

| Arson | 23.0 | 27 |

Since 1999, the overall crime rate of North Charleston has begun to decline. The total violent crime index rate for North Charleston for 1999 was 1043.5 crimes committed per 100,000 people, with the United States average at 729.6 per 100,000. North Charleston had a total violent crime index rate of 489.4 per 100,000 for the year of 2012, versus a national average of 296.0 per 100,000.

According to the Congressional Quarterly Press 2012 City Crime Rankings: Crime in Metropolitan America, North Charleston ranked as the 126th most dangerous American city larger than 75,000 inhabitants.[68][69] The entire Charleston-North Charleston-Summerville, SC Metropolitan Statistical Area had a lower overall crime rate ranking at #35.[70]

The 2010 Congressional Quarterly Press list of America's 400 most dangerous cities placed North Charleston at No. 63. The homicide rate alone decreased by 61%, and the lower crime rate removed North Charleston from the company of such cities as Detroit and St. Louis, placing it more in line with average, medium-sized Southern cities like Columbia and Chattanooga. City officials attributed the drop to the hard work of the North Charleston Police Department and the cooperation of city residents through "community policing" programs.[71] U.S. Attorney for the District of South Carolina Bill Nettles made community policing one of his statewide initiatives, starting the program in North Charleston in 2011.[72]

Education

editNorth Charleston is served by the Charleston County School District and Dorchester School District II.

Public high schools:

- North Charleston High School (CCSD)

- R.B. Stall High School (CCSD)

- Academic Magnet High School (CCSD)

- Military Magnet Academy (CCSD)[73]

- Fort Dorchester High School (DD2)

Private schools:

North Charleston is home to Charleston Southern University, Trident Technical College, and ECPI University.[74] Near the airport, in North Charleston, the Lowcountry Graduate Center offers satellite campus access to multiple universities in South Carolina. Clemson, University of South Carolina, Medical University of South Carolina, The Citadel and the College of Charleston all working together to provide Lowcountry residents with access to graduate degree programs together in one convenient location. Webster University maintains two locations, one at the Charleston AFB and another just off of Leeds Avenue.

Media

editBroadcast television

editThese TV stations have studios in and broadcast from North Charleston:

- WAZS-LD (29 Digital, Azteca America, independent), owned by Jabar Communications

- WTAT-TV (24, Fox), owned by Cunningham Broadcasting Company

- WMMP-TV (36, My Network Television), owned by Sinclair Broadcasting Company

Transportation

editRoads

edit|

Major highways

|

Major surface roads

|

Air

editCharleston International Airport and the Charleston Air Force Base, both located within the City of North Charleston, provide commercial and military air service for the region. The airport currently serves more than 2.9 million passengers annually. Commercial airlines include Alaska Airlines, Allegiant Air, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Frontier Airlines, JetBlue Airways, Southwest Airlines, and United Airlines.

Ports

editThe South Carolina State Ports Authority has six intermodal facilities, three of which are located in North Charleston. A new intermodal facility, Hugh K. Leatherman Terminal, is being built on the former Charleston Naval Base and Phase 1 opened in April 2021.[75][76] Each facility handles container, bulk, and break bulk cargo. With more than 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) of warehouse and storage space, the port terminals can accommodate more than 17 vessels at a time.

Today the Port of Charleston boasts the deepest water in the southeast region and regularly handles ships too big to transit through the Panama Canal. A next-generation harbor deepening project is underway to dredge the Port of Charleston's entrance channel to 54 feet and harbor channel to 52 feet at mean low tide.[77] Port terminals in North Charleston include:

- North Charleston Terminal – Used for container cargo, specializes in handling container ships 8,000 TEU and smaller, in North Charleston.[78]

- Veterans Terminal – Dedicated bulk, break-bulk, RO-RO, and project cargo facility in North Charleston.[79]

- Hugh K. Leatherman Sr. Terminal – 280-acre facility opened in April 2021 to be used for container cargo.[75] The new facility can handle ships up to 20,000 TEU and will increase port capacity by 50%. In North Charleston.[80]

- Wando Welch Terminal – Used for container vessels of all size, in the town of Mount Pleasant.[81]

- Columbus Street Terminal – Used for project cargo, break-bulk and roll-on/roll-off cargo, in Charleston.[82]

- Union Pier Terminal – Designed to move break-bulk cargo. Also home of cruise ship operations, in Charleston.[83][84]

Railroads

editAmtrak, Norfolk Southern, the CSX System and the South Carolina Railroad Commission provide passenger and freight rail service in North Charleston.

Bus

editNorth Charleston is served by a bus system, operated by the Charleston Area Regional Transportation Authority (CARTA). Most of the city is served by regional fixed route buses that are also equipped with bike racks as part of the system's Rack & Ride program. The North Charleston Intermodal Transportation Center will consolidate a new train station, long haul, and CARTA at one location.

Rural parts of North Charleston and the Tri-County metropolitan area are served by a different bus system, operated by Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Rural Transportation Management Association (BCD-RTMA).

City services

editPolice department

editThe North Charleston Police Department was formed in 1972 with 19 officers and five support personnel. In 2015, the department had approximately 416 employees.[85]

Fire department

editThe first fire department founded in the area to become North Charleston was the St. Phillip's and St. Michael's Fire Department in 1935, made up of volunteers. They had one station and one engine. The North Charleston Fire Department, also a volunteer group, was formed in 1937 with one station and one engine. In 1959, the departments merged to become the North Charleston Consolidated Fire Department. NCFD became a paid service in 1962, at which time all volunteers were released. They formed the organization today known as the Charleston County Volunteer Rescue Squad.[86]

The two departments were merged in 1996 as the North Charleston Fire Department. It had a total of 10 fire stations, 10 engines, 3 ladder trucks and 2 squads at that time.[86]

Currently, the NCFD has 13 stations, with one being a satellite station for the marine unit. The department has 12 engine companies, 2 aerial tower companies, 2 ladder companies, 2 rescue companies, 1 hazmat unit, 2 marine units, and 1 high water rescue unit in service.[87]

The department operates on a 24/48 shift schedule. The NCFD runs on average roughly 30,000 calls per year.[88]

Healthcare

editThe Trident Regional Medical Center is North Charleston's major hospital. Several other hospitals throughout the area serve city residents, including the Medical University of South Carolina, Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center, Bon Secours-St Francis Xavier Hospital and Roper Hospital, in Charleston. The East Cooper Regional Medical Center, in Mount Pleasant, also serves North Charleston residents.

The Emergency Medical Services for North Charleston are provided by Charleston County Emergency Medical Services and Dorchester County Emergency Medical Services. The city is served by both Charleston and Dorchester counties EMS and 911 services since the city is part of both counties.[89][90]

Notable people

edit- Rick Brewer, academic administrator

- Nehemiah Broughton, NFL player

- Al Cannon, former sheriff of Charleston County

- Mendel Jackson Davis, former representative for South Carolina's 1st congressional district (1971–1981)

- Carlos Dunlap, NFL defensive end[91]

- Jarred Fayson, NFL player

- Earl Grant, basketball player and coach

- Charles Marvin Green Jr. a.k.a. Angry Grandpa, YouTuber

- Nikki Greene, WNBA player

- Jarriel King, NFL player

- Byron Maxwell, NFL player

- Ronald Motley, lawyer

- S. Eugene Poteat, retired senior CIA executive

- L. Mendel Rivers, former representative for South Carolina's 1st congressional district (1941–1970)

- Tim Scott, U.S. senator for South Carolina

- Walter Scott, U.S. Coast Guard soldier, murdered during a traffic stop

- Art Shell, NFL player and coach

- John Simpson, NFL player

- Keith Stubbs, comedian

- Corey Washington, NFL player

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b City Planning Department (2008-07). City of North Charleston boundary map Archived December 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. City of North Charleston. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: North Charleston, South Carolina

- ^ a b c d e "QuickFacts: North Charleston city, South Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2020-2023". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "North Charleston (SC) sales tax rate". Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ National Register Properties in South Carolina

- ^ Trinkley, Michael and Debi Hacker (February 2008). Tranquil Hill Plantation: the most charming inland place. Chicora Foundation, Inc. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ South Carolina Historical Society (1918). Mabel Louise Webber (ed.). The South Carolina historical and genealogical magazine. Vol. 19. South Carolina Historical Society. pp. 29–31. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Edward (October 1, 1984). "Hibben House figured in events of Revolutionary War". The News and Courier. pp. 2–B. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Wise, Warren (March 22, 2008). N. Charleston assessed by its founding mayor. Post and Courier. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Glenn (June 19, 2010). Ex-N. Charleston mayor dead. Post and Courier. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ Brams, Sophie (November 7, 2023). "Reggie Burgess wins North Charleston mayor's race". WCBD-TV. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Joyce, Terry (March 16, 1996). "Charleston, Navy part company" Archived July 8, 2012, at archive.today, Post and Courier. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Bartelme, Tony and Doug Perdue (November 22, 2009). "Noisette: The future of the old Charleston Navy Base and a look at the deal that never happened"[permanent dead link], Post and Courier. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Chicora Life Center announced". City of North Charleston. July 7, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "UC Funds announces $13.9 million loan for Chicora Life Center project". Palmetto Business Daily. October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "Bennett Hofford completes Phase I HVAC work on Chicora Life Center". Palmetto Business Daily. October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ McDermott, John P. and Yvonne Wenger (October 29, 2009). Boeing Lands Here[permanent dead link]. Post and Courier. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Stech, Katy (December 8, 2010). "Noisette parcel gets new owner" Archived July 1, 2012, at archive.today, Post and Courier. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Bird, Allyson and Schuyler Kropf (December 23, 2010). "Summey promises fight over rail plan" Archived July 7, 2012, at archive.today, Post and Courier. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael (April 7, 2015). "South Carolina Officer Is Charged With Murder of Walter Scott". The New York Times. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Walter Scott Didn't Grab Taser, Man Who Recorded South Carolina Police Shooting Video Says". Los Angeles, California: KTLA 5. April 9, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (December 5, 2016). "Mistrial for South Carolina Officer Who Shot Walter Scott". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Station Name: SC CHARLESTON INTL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for CHARLESTON/MUNICIPAL, SC 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – North Charleston city, South Carolina". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – North Charleston city, South Carolina". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – North Charleston city, South Carolina". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Boeing: Boeing in South Carolina". www.boeing.com. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ Charleston, South Carolina Archived April 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stock, Kyle (June 11, 2005). Expanding call center brings jobs Archived July 7, 2012, at archive.today. Post and Courier. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ "Homepage". iQor. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Bruce (April 7, 2008). KapStone Paper buying 6 MeadWestvaco mills for $485 million. Times and Democrat. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Maze, Jonathan (December 6, 2002). Daimler subsidiary to bring area 200 jobs Archived July 1, 2012, at archive.today. Post and Courier. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Williams, Charles (February 28, 2000). Bosch plant a leader in Lowcountry Archived July 10, 2012, at archive.today. Post and Courier. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Press release (July 11, 2008). Jet engine supplier opens in North Charleston Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. SCBIZ Daily. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ Badger, Emily; Bui, Quoctrung (April 7, 2018). "In 83 Million Eviction Records, a Sweeping and Intimate New Look at Housing in America". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "NWS Charleston, SC - About Our Office". www.weather.gov. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ "NWS Charleston Navy Base in Goose Creek, SC | MilitaryBases.com". Military Bases. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "South Carolina Military Bases - Military Bases in South Carolina". www.sciway.net. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "Naval Base History". Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Charleston History | Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers". www.fletc.gov. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Jill Coley, "Military striving to fix health care ills" Archived 2008-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, The Post and Courier, January 4, 2008.

- ^ a b "Charleston Naval Weapon Station, Charleston, South Carolina". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Charleston Naval Shipyard". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "History". cnrse.cnic.navy.mil. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Joint Base Charleston Air Force North in Charleston, SC | MilitaryBases.com". Military Bases. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "About Us". www.jbcharleston.jb.mil. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Protocol". Joint Base Charleston. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "628th Air Base Wing". U.S. Air Force Expeditionary Center. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Slade, Robert Behre David. "State railroad division pays $10 million for remaining Noisette properties on former Navy Base". Post and Courier. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Dennis, Jr., Rickey Ciapha. "Former Charleston Naval Base focus of national urban planning competition". Post and Courier. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Charleston Area Convention Center facility information Archived July 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. SMG. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ North Charleston Coliseum facility information Archived February 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. SMG. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ North Charleston Performing Arts Center facility information Archived February 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. SMG. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Project, SC Picture (July 12, 2000). "Jenkins Orphanage". SC Picture Project. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Our History". www.jenkinsinstitute.org. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Jenkins Orphanage Band - Charleston, South Carolina". www.sciway.net. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ http://parkcirclefilms.org Archived March 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Government", City of North Charleston official website

- ^ "North Charleston to open state of the art Public Works complex – City of North Charleston, SC". Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "History & Cultural Heritage". City of North Charleston. 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ 2012 City Crime Rate Rankings Archived February 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. CQ Press. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ CQ Press: City Crime Rankings 2009 Archived September 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. CQ Press. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ 2012 Metropolitan Crime Rate Rankings Archived July 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. CQ Press. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ Hicks, Brian (November 26, 2010). City finally off crime naughty list. Post and Courier. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Knich, Diane (February 15, 2017). "North Charleston hires former U.S. Attorney Bill Nettles to help launch police advisory group". The Post and Courier. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Military Magnet Academy". www.ccsdschools.com. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ "About the Charleston Campus". www.ecpi.edu. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "Charleston Opens First New U.S. Container Terminal in 12 Years". The Maritime Executive. April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "Hugh K. Leatherman Terminal" (PDF). South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Harbor Deepening". SCSPA.com. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "North Charleston Terminal". South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Veterans Terminal". South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Hugh K. Leatherman Terminal". South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Wando Welch Terminal". South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Columbus Street Terminal". South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Union Pier Terminal". South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Cruise Terminal". South Carolina Ports Authority. October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Police and Public Safety – City of North Charleston, SC". Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "The History of NCFD – City of North Charleston, SC". Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Stations & Equipment – City of North Charleston, SC". Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Operations – City of North Charleston, SC". Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Emergency Medical Services (EMS)". www.charlestoncounty.org. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Emergency Medical Services (EMS) | Dorchester County, SC website". www.dorchestercountysc.gov. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Carlos Dunlap player profile". FloridaGators.com.

Further reading

edit- "North Charleston Recreation Department 2010 Information Guide" (PDF). December 22, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2010.