Norman Holmes Pearson (April 13, 1909 – November 5, 1975) was an American academic at Yale University, and a prominent counterintelligence agent during World War II. As a specialist on American literature and department chairman at Yale University he was active in establishing American Studies as an academic discipline.[1]

Norman Holmes Pearson | |

|---|---|

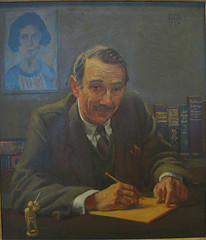

Portrait of Prof. Norman Holmes Pearson by Deane Keller. |

Career

editHe was born in Gardner, Massachusetts, to a locally prominent family that owned a chain of department stores. Pearson attended Gardner schools and Phillips Andover Academy (1927-1928). He graduated Yale College in 1932 with a A.B. in English.[2] After a scholarship at the University of Oxford, he was awarded a second A.B. and later an M.A. from Oxford. In 1937, while still a Yale graduate student, he and William Rose Bénet published the two-volume Oxford Anthology of American Literature and later co-edited five volumes on Poets of the English Language with poet W.H. Auden. He became a Yale faculty member, Instructor of English, and eventually Professor of English and of American Studies. He took his PhD in 1941 and was a specialist on Nathaniel Hawthorne. He maintained close personal relations with major literary figures, especially including poets H.D., whose daughter became his secretary in the OSS,[3] and Ezra Pound, promoting their careers and helping Pound avoid a charge of treason.[4] "Throughout his life he played the role of the man of letters, encouraging poets, writers, painters, and scholars..."[5] He was twice a Guggenheim Fellow, in 1948 and 1956.

Pearson was recruited by Donald Downes to work for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), in London during World War II. By 1943 Pearson was working under James R. Murphy as part of the new X-2 CI (counterintelligence) branch that served as the link between the OSS and the British Ultra cryptoanalysis project in nearby Bletchley Park. Working with British Special Intelligence (SI), X-2 helped turn all of Germany's secret agents in Britain and exposed a network of 85 enemy agents in Mozambique. By 1944 there were sixteen X-2 field stations and nearly a hundred on staff. Pearson said the British 'were the ecologists of double agency: everything was interrelated, everything must be kept in balance.'"[6] In addition, the Art Looting Investigation Unit reported directly to him; the 2013 movie "Monuments Men" concerns that unit. Robin Winks says "Some of his best work, done for the OSS in its final months, were analyses of the intelligence services of other nations."[7] Following the war he helped organize the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). To head counterintelligence for the new agency he helped recruit James Jesus Angleton, who had been his "number two" in the OSS in London and head of X-2 Italy.

Pearson turned down a position at the State Department to return to academe. He co-founded and headed Yale's new American Studies program, in which scholarship became an instrument for promoting American interests during the Cold War, such as recruiting personnel for the CIA and other agencies. Popular among undergraduates, the program sought to instruct them in what the program viewed as the fundamentals of American civilization and thereby instill a sense of nationalism and national purpose. It was also used as a recruiting vehicle for foreign students who, after their return to their home countries, might be useful to US foreign policy objectives.[8] Also during the 1940s and 1950s, Wyoming millionaire William R. Coe made large contributions to the American Studies programs at Yale in order to celebrate American values and defeat the "threat of communism".[9] Pearson had realized "that the international standing of American Studies at Yale to no small degree depended on the attraction of the program for foreign students and on the continued ties between those scholars and the program ... Norman was Yale. There were many brilliant scholars and teachers, but he was the one who cared.".[10]

Archivist

editPearson worked with Donald C. Gallup to redirect the focus of the Yale Collection of American Literature, emphasizing archival collections of twentieth-century writers. It is through the extended concept of "archives" that the collection has acquired its extra-literary materials such as photographs, works of art, and memorabilia.[11]

Brenda Helt, in The Making and Managing of American Modernists: Norman Holmes Pearson and the Yale Collection of American Literature, based in part on Pearson's unpublished letters, examines his role in developing that collection. He used his personal connections with authors like H. D., Bryher, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein to acquire major collections of their work for Yale. Reciprocally, Pearson used his authoritative position to further interest in and obtain publishers for the work of these modernists, securing their reputations for posterity and facilitating the success of some of their best work. Pearson worked tirelessly as H.D.'s tactful editor, as well as her literary advisor and (unpaid) agent, roles that had a significant positive effect on the quantity and quality of her late work. Pearson promoted Pound's work apart from his political involvements, helping to prevent it from being "disappeared" due to Pound's very unpopular World War II politics and consequent incarceration at St. Elizabeths Hospital (a psychiatric hospital operated by the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health).

Personal life

editPearson was the son of Chester Page Pearson and Fanny Kittredge Pearson, whose home on Elm Street in Gardner, Massachusetts "was often the scene of serious discussions between the leading bankers, businessmen, and political figures" of the city. Chester Page Pearson was president of Goodnow Pearson & Co. and Gardner's first Mayor. He was descended from an old Yankee family.

Pearson's mother Fanny Holmes Kittredge Pearson of Nelson and Jaffrey, New Hampshire, was descended from William and Mary Brewster, Congregationalist Separatists.

After a fall during childhood, Pearson suffered from tuberculosis of the hip and was confined to a wheelchair for much of his childhood and undergraduate career at Yale, which began in 1928. As an adult he was severely underweight and walked with a pronounced limp that developed into a shuffle. His doctoral studies were seriously delayed by a series of operations and he did not complete his Ph.D. until 1941. Yet he celebrated V-E Day (the German surrender) by "climbing well up on one of the stone lions in Trafalgar Square" and was "the first American officer to enter Oslo after the German capitulation in 1945" and "refused to think of himself as handicapped"[12] and was well known for his vise-like handshake (Winks 264). As a Yale undergraduate he was an editor of the Yale Daily News and a winner of the Henry H. Strong Prize for American Literature for an essay on Nathaniel Hawthorne and thereafter realigned his studies from economics to English and American literature.

On February 21, 1941 Pearson married Susan Silliman Bennett (1904–1987), who had two daughters from a previous marriage, Susan S. Tracy (later Susan Addiss) and Elizabeth B. Tracy. Pearson's remains are buried in New Haven's historic Grove Street Cemetery. His papers, the Norman Holmes Pearson Collection, are deposited with Yale's Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Honors

edit- Guggenheim Fellowship (twice, 1948 and 1956).

- President, American Studies Association, 1968

- Chancellor, Academy of American Poets

- National Book Award committee

- Medal of Freedom, US, September 6, 1945.[13]

- Médaille de la Reconnaissance française, France.[13]

- Légion d'honneur, Chevalier, France.[13]

- Order of St. Olav, Knight's Cross, 1st class, Norway.[13]

Selected works

editPearson's prolific output encompassed 164 works in 246 publications in 4 languages and 10,656 library holdings.[14]

The most widely held works by Pearson include:

- The Complete Novels and Selected Tales of Nathaniel Hawthorne by Nathaniel Hawthorne (ed. Pearson), 4 editions published between 1937 and 1965 in English and held by 1,954 libraries worldwide.[14]

- The Oxford Anthology of American Literature (ed. Pearson), 11 editions published between 1938 and 1963 in English and held by 1,080 libraries worldwide.[14]

- End to Torment: a Memoir of Ezra Pound by H.D. (H.D.)(ed. Pearson), 2 editions published between 1979 and 1980 in English and held by 1,068 libraries worldwide.[14]

- Between History & Poetry the Letters of H.D. & Norman Holmes Pearson by H. D. (ed. Pearson), 4 editions published in 1997 in English and held by 949 libraries worldwide.[14]

- The Letters by Nathaniel Hawthorne (ed. Pearson), in English and held by 565 libraries worldwide

- Decade; a Collection of Poems from the First Ten Years of the Wesleyan Poetry Program (ed. Pearson), 1 edition published in 1969 in English and held by 516 libraries worldwide.[14]

- The Portable Romantic Poets (ed. Pearson), 3 editions published between 1977 and 2006 in English and held by 209 libraries worldwide.[14]

- Poets of the English Language (5 vols., eds. W. H. Auden & Pearson), 6 editions published between 1950 and 1977 in English and held by 1,576 libraries worldwide.[14] Volumes published separately include Restoration and Augustan Poets and Victorian and Edwardian Poets.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "NORMAN H. PEARSON, AN ENGLISH SCHOLAR". The New York Times. November 7, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "NORMAN H. PEARSON, AN ENGLISH SCHOLAR". The New York Times. November 7, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Rosenheim, Shawn James (March 24, 2020). The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-3716-3.

- ^ Kopley, Emily, "Art for the Wrong Reason: Paintings by Poets," The New Journal. December 2004.

- ^ Winks p. 310

- ^ Timothy Naftali, "Blind Spot", The New York Times, July 10, 2005."

- ^ Winks, Robin W. (1996), Cloak & Gown: Scholars in the Secret War, 1939-1961, pp. 247–321.

- ^ Michael Holzman, "The Ideological Origins of American Studies at Yale," American Studies 40:2 (Summer 1999): 71-99

- ^ Liza Nicholas, "Wyoming as America: Celebrations, a Museum, and Yale," American Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Sep. 2002), pp. 437–465 in JSTOR

- ^ Quoted in Winks, p. 321; see footnote 87 for primary source.

- ^ Willis, Patricia C. "Collection of American Literature," Yale University Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. February 11, 2005.

- ^ Winks 251

- ^ a b c d (H.D.) et al. (1997). Between History and Poetry: the Letters of H.D. and Norman Holmes Pearson, p. 55; Winks, p. 321.

- ^ a b c d e f g h WorldCat Identities: Norman Holmes Pearson

Further reading

edit- Barnhisel, Greg: Code Name Puritan : Norman Holmes Pearson at the Nexus of Poetry, Espionage, and American Power. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2024, ISBN 978-0-226-64720-3

- Holtzman, Michael. "The Ideological Origins of American Studies at Yale," American Studies 40:2 (Summer 1991) 71-99.

- Kopley, Emily. "Art for the Wrong Reason: Paintings by Poets," The New Journal. December 2004.

- Winks, Robin W. (1996). Cloak & Gown: Scholars in the Secret War, 1939-1961. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06524-4; OCLC 34671805

Primary sources

edit- Pearson, Norman Holmes, and L. S. Dembo. "Norman Holmes Pearson on HD: an interview." Contemporary Literature 10.4 (1969): 435-446. in JSTOR

- James Laughlin, Peter Glassgold, New Directions 42

External links

editArchival resources

edit- Norman Holmes Pearson Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- "Pearson Norman Holmes, 1901-1975," Arlin Turner Papers, 1927–1980, Duke University Libraries.