The Eurovision Song Contest 1999 was the 44th edition of the Eurovision Song Contest, held on 29 May 1999 at the International Convention Centre in Jerusalem, Israel. Organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and host broadcaster Israel Broadcasting Authority (IBA), the contest was held in the country following its victory at the 1998 contest with the song "Diva" by Dana International, and was presented by Dafna Dekel, Yigal Ravid and Sigal Shachmon.

| Eurovision Song Contest 1999 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dates | |

| Final | 29 May 1999 |

| Host | |

| Venue | International Convention Centre Jerusalem, Israel |

| Presenter(s) | |

| Directed by | Hagai Mautner |

| Executive supervisor | Christine Marchal-Ortiz |

| Executive producer | Amnon Barkai |

| Host broadcaster | Israel Broadcasting Authority (IBA) |

| Website | eurovision |

| Participants | |

| Number of entries | 23 |

| Debuting countries | None |

| Returning countries | |

| Non-returning countries | |

| |

| Vote | |

| Voting system | Each country awarded 12, 10, 8–1 points to their ten favourite songs |

| Winning song | |

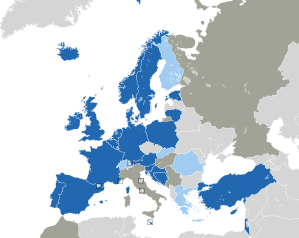

Twenty-three countries participated in the contest. Finland, Greece, Macedonia, Romania, Slovakia, and Switzerland, having participated in the 1998 contest, were absent due to being relegated after achieving the lowest average points totals over the past five contests, while Hungary actively chose not to return. Meanwhile Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Denmark, and Iceland returned to the contest, having last participated in 1997, while Lithuania made its first contest appearance since 1994.

The winner was Sweden with the song "Take Me to Your Heaven", composed by Lars Diedricson, written by Gert Lengstrand and performed by Charlotte Nilsson. Iceland, Germany, Croatia, and Israel rounded out the top five, with Iceland achieving its best ever result and Croatia equalling its previous best. It was the first contest since 1976 that countries were allowed to perform in the language of their choice, and not necessarily the language of their country. It was also the first ever contest not to feature an orchestra or live music accompanying the competing entries.

Location

editThe 1999 contest took place in Jerusalem, Israel, following the country's victory at the 1998 edition with the song "Diva", performed by Dana International. It was the second time that Israel had staged the contest, following the 1979 contest also held in Jerusalem.[1] The selected venue was the Ussishkin Auditorium of the International Convention Centre, commonly known in Hebrew as Binyenei HaUma (Hebrew: בנייני האומה), which also served as the host venue for Israel's previous staging of the event.[2][3][4]

The prospect of Israel staging the contest resulted in protest by members of the Orthodox Jewish community in the country, including opposition by the deputy mayor of Jerusalem Haim Miller to the contest being staged in the city.[5][6] Additional concerns over funding for the event also contributed to speculation that the contest could be moved to Malta or the United Kingdom, the nations which had finished in the top three alongside Israel the previous year.[7] Financial guarantees by the Israeli government however helped to ensure that the contest would take place in Israel. The possibility of holding the event in an open air venue was discussed, however concerns over security led to the choice of an indoor venue for the event.[3] A tight security presence was felt during the rehearsal week as a precaution against potential disruption from Palestinian militant groups.[8][9]

Participating countries

edit| Eurovision Song Contest 1999 – Participation summaries by country | |

|---|---|

Per the rules of the contest, twenty-three countries were allowed to participate in the event, a reduction from the twenty-five which took part in the 1997 and 1998 contests.[3][10] Lithuania made its first appearance since 1994, and Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Denmark, and Iceland returned after being relegated from the previous year's event.[3] Russia was unable to return from relegation due to failing to broadcast the 1998 contest, as specified in the rules for that edition.[3][11] 1998 participants Finland, Greece, Hungary, North Macedonia, Romania, Slovakia, and Switzerland were absent from this edition.[2][3]

Several of the performers taking part in the contest had previously competed as lead artists in past editions. Two artists returned as lead artists in this year's event, with Croatia's Doris Dragović having taken part in 1986 representing Yugoslavia, and Slovenia's Darja Švajger making a second appearance for her country following the 1995 contest.[12] A number of former competitors also returned to perform as backing vocalists for some of the competing entries: Stefán Hilmarsson, who represented Iceland twice in 1988 and 1991, provided backing vocals for Selma;[13] Kenny Lübcke, who represented Denmark in 1992, returned to provide backing for Trine Jepsen and Michael Teschl;[14] Christopher Scicluna and Moira Stafrace, who represented Malta in 1994, provided backing for Times Three;[15] Gabriel Forss, who represented Sweden in 1997 as a member of the group Blond, was among Charlotte Nilsson's backing vocalists;[16][17] and Linda Williams, who represented the Netherlands in 1981, returned as a backing vocalist for Belgium's Vanessa Chinitor.[18] Additionally, Evelin Samuel competed for Estonia in this year's contest, having previously served as backing vocalist for Maarja-Liis Ilus in 1997.[19]

| Country | Broadcaster | Artist | Song | Language | Songwriter(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | ORF | Bobbie Singer | "Reflection" | English | Dave Moskin |

| Belgium | VRT | Vanessa Chinitor | "Like the Wind" | English |

|

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | RTVBiH | Dino and Béatrice | "Putnici" | Bosnian, French | Dino Dervišhalidović |

| Croatia | HRT | Doris | "Marija Magdalena" | Croatian | |

| Cyprus | CyBC | Marlain | "Tha'ne erotas" (Θα'ναι έρωτας) | Greek |

|

| Denmark | DR | Trine Jepsen and Michael Teschl | "This Time I Mean It" | English | Ebbe Ravn |

| Estonia | ETV | Evelin Samuel and Camille | "Diamond of Night" | English |

|

| France | France Télévision | Nayah | "Je veux donner ma voix" | French |

|

| Germany | NDR[a] | Sürpriz | "Journey to Jerusalem – Kudüs'e Seyahat" | German, Turkish, English | |

| Iceland | RÚV | Selma | "All Out of Luck" | English |

|

| Ireland | RTÉ | The Mullans | "When You Need Me" | English | Bronagh Mullan |

| Israel | IBA | Eden | "Happy Birthday" | English, Hebrew |

|

| Lithuania | LRT | Aistė | "Strazdas" | Samogitian |

|

| Malta | PBS | Times Three | "Believe 'n Peace" | English |

|

| Netherlands | NOS | Marlayne | "One Good Reason" | English |

|

| Norway | NRK | Van Eijk | "Living My Life Without You" | English | Stig André van Eijk |

| Poland | TVP | Mietek Szcześniak | "Przytul mnie mocno" | Polish |

|

| Portugal | RTP | Rui Bandeira | "Como tudo começou" | Portuguese |

|

| Slovenia | RTVSLO | Darja Švajger | "For a Thousand Years" | English | Primož Peterca |

| Spain | TVE | Lydia | "No quiero escuchar" | Spanish |

|

| Sweden | SVT | Charlotte Nilsson | "Take Me to Your Heaven" | English |

|

| Turkey | TRT | Tuba Önal and Grup Mistik | "Dön Artık" | Turkish |

|

| United Kingdom | BBC | Precious | "Say It Again" | English | Paul Varney |

Qualification

editDue to the high number of countries wishing to enter the contest, a relegation system was introduced in 1993 in order to reduce the number of countries which could compete in each year's contest. Any relegated countries would be able to return the following year, thus allowing all countries the opportunity to compete in at least one in every two editions.[10][24] The relegation rules introduced for the 1997 contest were again utilised ahead of the 1999 contest, based on each country's average points total in previous contests. The twenty-three participants were made up of the previous year's winning country and host nation, the seventeen countries other than the host which had obtained the highest average points total over the preceding five contests, and any eligible countries which had not competed in the 1998 contest. In cases where the average was identical between two or more countries, the total number of points scored in the most recent contest determined the final order.[10]

A new addition to the relegation rules specified that for the 2000 contest and future editions, the four largest financial contributors to the contest – France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom – would automatically qualify for each year's event and be exempt from relegation.[10] This new "Big Four" group of countries was created to ensure the financial viability of the event, and was prompted by a number of poor placements in previous years for some of these countries, which if repeated in 1999 could have resulted in those countries being eliminated.[3][7]

Finland, Greece, Hungary, North Macedonia, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, and Switzerland were therefore excluded from participating in the 1999 contest, to make way for the return of Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Denmark, Iceland, and Lithuania, and new debuting country Latvia. However Latvia's Latvijas Televīzija subsequently withdrew its participation at a late stage, and their place in the contest was subsequently offered to Hungary as the excluded country with the highest average points total. Hungarian broadcaster Magyar Televízió declined and the offer was then passed to Portugal's Rádio e Televisão de Portugal as the next country in line, which accepted.[2][3][7]

The calculations used to determine the countries relegated for the 1999 contest are outlined in the table below.

Table key

- Qualifier

- ‡ Automatic qualifier

- † Returning countries which did not compete in 1998

| Rank | Country | Average | Yearly Point Totals[25][26][27][28][29] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | |||

| 1 | Ireland | 130.60 | 226 | 44 | 162 | 157 | 64 |

| 2 | Israel ‡ | 126.50 | R | 81 | DNQ | 172 | |

| 3 | United Kingdom | 121.80 | 63 | 76 | 77 | 227 | 166 |

| 4 | Malta | 94.40 | 97 | 76 | 68 | 66 | 165 |

| 5 | Norway | 83.40 | 76 | 148 | 114 | 0 | 79 |

| 6 | Croatia | 74.20 | 27 | 91 | 98 | 24 | 131 |

| 7[c] | Sweden | 67.40 | 48 | 100 | 100 | 36 | 53 |

| 8[c] | Cyprus | 67.40 | 51 | 79 | 72 | 98 | 37 |

| 9[d] | Netherlands | 59.25 | 4 | R | 78 | 5 | 150 |

| 10[d] | Germany | 59.25 | 128 | 1 | DNQ | 22 | 86 |

| 11 | Denmark † | 58.50 | R | 92 | DNQ | 25 | R |

| 12 | Poland | 57.00 | 166 | 15 | 31 | 54 | 19 |

| 13 | France | 56.80 | 74 | 94 | 18 | 95 | 3 |

| 14 | Turkey | 56.00 | R | 21 | 57 | 121 | 25 |

| 15 | Spain | 54.00 | 17 | 119 | 17 | 96 | 21 |

| 16 | Estonia | 53.50 | 2 | R | 94 | 82 | 36 |

| 17 | Belgium | 50.67 | R | 8 | 22 | R | 122 |

| 18 | Slovenia | 44.25 | R | 84 | 16 | 60 | 17 |

| 19 | Hungary[e] | 42.00 | 122 | 3 | DNQ | 39 | 4 |

| 20 | Austria † | 41.50 | 19 | 67 | 68 | 12 | R |

| 21 | Portugal[e] | 41.20 | 73 | 5 | 92 | 0 | 36 |

| 22 | Greece | 39.80 | 44 | 68 | 36 | 39 | 12 |

| 23 | Iceland † | 37.25 | 49 | 31 | 51 | 18 | R |

| 24 | Bosnia and Herzegovina † | 22.00 | 39 | 14 | 13 | 22 | R |

| 25 | Macedonia | 16.00 | DNQ | R | 16 | ||

| 26[f] | Finland | 14.00 | 11 | R | 9 | R | 22 |

| 27[f] | Slovakia | 14.00 | 15 | R | 19 | R | 8 |

| 28 | Switzerland | 10.50 | 15 | R | 22 | 5 | 0 |

| 29 | Romania | 10.00 | 14 | R | DNQ | R | 6 |

| 30 | Lithuania † | 0.00 | 0 | R | |||

Production

editThe Eurovision Song Contest 1999 was produced by the Israel Broadcasting Authority (IBA). Amnon Barkai served as executive producer, Aharon Goldfinger-Eldar served as producer, Hagai Mautner served as director, and Maya Hanoch, Mia Raveh and Ronen Levin served as designers.[2][30] On behalf of the contest organisers, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), the event was overseen by Christine Marchal-Ortiz as executive supervisor.[31][32][33] Usually able to hold a maximum of 3,000 people, modifications made to the Ussishkin Auditorium reduced the capacity to around 2,000 for the contest, with rows of seats removed from the floor to make room for the stage and from the balcony to allow for the construction of boxes for use by various commentators.[3][34]

Rehearsals in the venue for the competing acts began on 24 May 1999. Each country had two technical rehearsals in the week approaching the contest: the first rehearsals took place on 24 and 25 May, with each country allowed 40 minutes total on stage followed by a 20 minute press conference; the second rehearsals subsequently took place on 26 and 27 May, with each country allocated 30 minutes on stage.[3] Each country took to the stage in the order in which they would perform, however the Lithuanian delegation was permitted to arrive in Israel one day later than the other delegations due to budget concerns.[35] Subsequently the first day's rehearsals began with Belgium as the second country to perform in the contest, with Lithuania being the last country to complete their first rehearsal on the second day; the order of rehearsals was corrected for the second rehearsals, with Lithuania scheduled as the first delegation on stage. Additional rehearsals took place on 26 May for the contest's concluding performance with all artists, and on 27 May for the contest's presenters and to test the voting scoreboard's computer graphics. Two dress rehearsals held on 28 May were held with an audience, the second of which was also recorded as a production stand-by in case of problems during the live contest. A further dress rehearsal took place on the afternoon of 29 May ahead of the live contest, followed by security and technical checks.[3]

The singer Dafna Dekel, the radio and television presenter Yigal Ravid and the model and television presenter Sigal Shachmon were the presenters of the 1999 contest, the first edition to feature three presenters in a single show.[12] Dekel had previously represented Israel in the 1992 contest and placed sixth with the song "Ze Rak Sport".[36] The writers of the winning song were awarded with a trophy designed by Yaacov Agam, which was presented by the previous year's winning artist Dana International.[37][38][39]

A compilation album featuring many of the competing entries was released in Israel following the contest, commissioned by IBA and released through the Israeli record label IMP Records. The release contained nineteen of the twenty-three competing acts on CD and an additional video CD with clips from the televised broadcast and footage from backstage.[40][41]

Format

editEntries

editEach participating broadcaster was represented in the contest by one song, no longer than three minutes in duration. A maximum of six performers were allowed on stage during each country's performance, and all performers were required to be at least 16 years old in the year of the contest. Selected entries were not permitted to be released commercially before 1 January 1999, and were then only allowed to be released in the country they represented until after the contest was held. Entries were required to be selected by each country's participating broadcaster by 15 March, and the final submission date for all selected entries to be received by the contest organisers was set for 29 March. This submission was required to include a sound recording of the entry and backing track for use during the contest, a video presentation of the song on stage being performed by the artists, and the text of the song lyrics in its original language and translations in French and English for distribution to the participating broadcasters, their commentators and juries.[10]

For the first time since the 1976 contest the participants had full freedom to perform in any language, and not simply that of the country they represented.[12][42][g] This led to a marked increase in the number of entries which were performed in English.[12] Additionally, the rules were modified to make the orchestra a non-obligatory feature of the contest of which organising broadcasters were free to opt out.[10] IBA chose not to provide an orchestra, with all entries subsequently being performed with backing tracks, and no orchestra has been included as part of the competition since.[3][12]

Following the confirmation of the twenty-three competing countries, the draw to determine the running order was held on 17 November 1998.[10][21]

Voting procedure

editThe results of the 1999 contest were determined using the scoring system introduced in 1975: each country awarded twelve points to its favourite entry, followed by ten points to its second favourite, and then awarded points in decreasing value from eight to one for the remaining songs which featured in the country's top ten, with countries unable to vote for their own entry.[10][43] Each participating country was required to use televoting to determine their points, with viewers able to register their vote by telephone for a total of five minutes following the performance of the last competing entry.[10][44] Viewers could vote by calling one of twenty-two different telephone numbers to represent the twenty-three competing entries except that which represented their own country.[10][37] Once phone lines were opened a video recap containing short clips of each competing entry with the accompanying phone number for voting was shown in order to aid viewers during the voting window.[37] Systems were also put in place to prevent lobby groups from one country voting for their entry by travelling to other countries.[10]

Countries which were unable to hold a televote due to technological limitations were granted an exception, and their points were determined by an assembled jury of eight individuals, which was required to be split evenly between members of the public and music professionals, comprised additionally of an equal number of men and women, and below and above 30 years of age. Countries using televoting were also required to appoint a back-up jury of the same composition which would be called into action upon technical failure preventing the televote results from being used. Each jury member voted in secret and awarded between one and ten votes to each participating song, excluding that from their own country and with no abstentions permitted. The votes of each member were collected following the country's performance and then tallied by the non-voting jury chairperson to determine the points to be awarded. In any cases where two or more songs in the top ten received the same number of votes, a show of hands by all jury members was used to determine the final placing; if a tie still remained, the youngest jury member would have the deciding vote.[10]

Postcards

editEach entry was preceded by a video postcard which served as an introduction to each country, as well as providing an opportunity to showcase the running artistic theme of the event and to create a transition between entries to allow stage crew to make changes on stage.[45][46] The postcards for the 1999 contest featured animations of paintings of biblical stories which transitioned into footage of modern locations in Israel or clips representing specific themes related to contemporary Israeli culture and industries. The various locations or themes for each postcard are listed below by order of performance:[37]

- Lithuania – Jacob's Ladder; Israel Museum, Jerusalem

- Belgium – Pharaoh and his Army; Eilat

- Spain – Noah's Ark; landscapes of Galilee

- Croatia – Ruth; Israeli agriculture

- United Kingdom – Jonah and the Whale; Jaffa

- Slovenia – Adam and Eve; Israeli fashion

- Turkey – The Sea of Galilee; Tiberias and surroundings

- Norway – Workers of the Tabernacle; Israeli tech and virtual reality

- Denmark – Joseph and His Brothers; Haifa

- France – The Golden Calf; Israeli jewellery industry

- Netherlands – The Prophet; Tel Aviv nightlife

- Poland – David and Goliath; Israeli sports

- Iceland – The Manna from Heaven; Israeli culinary

- Cyprus – The Basket of Moses; rafting on the Jordan River

- Sweden – David and Bathsheba; music and art on the roofs of Tel Aviv

- Portugal – Daniel and the Lions; Acre

- Ireland – Cain and Abel; Judaean Desert

- Austria – The Judgement of Solomon; Jerusalem

- Israel – The Promised Land; Jezreel Valley

- Malta – David and Michal; Suzanne Dellal Centre for Dance and Theatre, Tel Aviv

- Germany – The Tower of Babel; Israeli beaches

- Bosnia and Herzegovina – Samson; Caesarea National Park

- Estonia – The Zodiac mosaic at the Old Beth Alfa Synagogue; love at the Dead Sea

Contest overview

editThe contest took place on 29 May 1999 at 22:00 (IST) and lasted 3 hours and 13 minutes.[10][22]

The show began with a computer animation entitled "From Birmingham to Jerusalem", highlighting the contest's journey from last year's host country the United Kingdom to Israel, and containing notable landmarks and features of the competing countries; the animation then transitioned into recorded footage of Jerusalem including dancers and hosts Dekel and Shachmon.[37] The contest's opening segment also featured Izhar Cohen and Gali Atari, Israel's previous winning artists from the 1978 and 1979 contests attending as special guests, and the previous year's co-presenter Terry Wogan in attendance as the United Kingdom's television commentator.[22][37] A pause between entries was included for the first time to allow broadcasters to provide advertisements during the show;[12] placed between the Polish and Icelandic entries, a performance of the song "To Life" from the musical Fiddler on the Roof featuring co-presenters Dekel and Shachmon was provided for the benefit of the audience in the arena and for non-commercial broadcasters.[22][37]

The contest's pre-recorded interval act entitled "Freedom Calls", shown following the final competing entry and during the voting window, was staged outside the Walls of Jerusalem and the Tower of David and featured performances by a troupe of dancers, a chorus and Dana International singing the D'ror Yikra and a cover of "Free", originally recorded by Stevie Wonder.[6][37][39] Following the traditional reprise performance of the winning song, the show finished with a performance of the English version of Israel's 1979 contest winning song "Hallelujah", which included all the competing artists and was featured as a tribute to the victims of the then-ongoing Kosovo War and to the people of the Balkans who were unable to watch the contest following the bombing of television services in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[2][12]

The winner was Sweden represented by the song "Take Me to Your Heaven", composed by Lars Diedricson, written by Gert Lengstrand and performed by Charlotte Nilsson.[47] This marked Sweden's fourth victory in the contest, following wins in 1974, 1984 and 1991, and occurred 25 years after ABBA brought Sweden its first victory.[44][48] Iceland, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina also achieved their best results to date, placing second, fourth and seventh respectively.[49][50][51]

During the presentation of the trophy to the contest winners, Dana International caused a security alert in the auditorium as while lifting the trophy she lost her balance and fell to the stage along with the winning songwriters before being helped up by security agents.[2][7][52]

The Norwegian delegation raised an objection to the use of simulated male vocals during the performance of Croatian entry "Marija Magdalena".[7] Following the contest this was found to have contravened the contest rules regarding the use of vocals on the backing tracks, and Croatia were sanctioned by the EBU with the loss of 33% of their points for the purpose of calculating their average points total for qualification in following contests.[2][53] The country's position and points at this contest however remain unchanged.[22]

The table below outlines the participating countries, the order in which they performed, the competing artists and songs, and the results of the voting.

| R/O | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lithuania | Aistė | "Strazdas" | 13 | 20 |

| 2 | Belgium | Vanessa Chinitor | "Like the Wind" | 38 | 12 |

| 3 | Spain | Lydia | "No quiero escuchar" | 1 | 23 |

| 4 | Croatia | Doris | "Marija Magdalena" | 118 | 4 |

| 5 | United Kingdom | Precious | "Say It Again" | 38 | 12 |

| 6 | Slovenia | Darja Švajger | "For a Thousand Years" | 50 | 11 |

| 7 | Turkey | Tuba Önal and Grup Mistik | "Dön Artık" | 21 | 16 |

| 8 | Norway | Van Eijk | "Living My Life Without You" | 35 | 14 |

| 9 | Denmark | Trine Jepsen and Michael Teschl | "This Time I Mean It" | 71 | 8 |

| 10 | France | Nayah | "Je veux donner ma voix" | 14 | 19 |

| 11 | Netherlands | Marlayne | "One Good Reason" | 71 | 8 |

| 12 | Poland | Mietek Szcześniak | "Przytul mnie mocno" | 17 | 18 |

| 13 | Iceland | Selma | "All Out of Luck" | 146 | 2 |

| 14 | Cyprus | Marlain | "Tha'ne erotas" | 2 | 22 |

| 15 | Sweden | Charlotte Nilsson | "Take Me to Your Heaven" | 163 | 1 |

| 16 | Portugal | Rui Bandeira | "Como tudo começou" | 12 | 21 |

| 17 | Ireland | The Mullans | "When You Need Me" | 18 | 17 |

| 18 | Austria | Bobbie Singer | "Reflection" | 65 | 10 |

| 19 | Israel | Eden | "Happy Birthday" | 93 | 5 |

| 20 | Malta | Times Three | "Believe 'n Peace" | 32 | 15 |

| 21 | Germany | Sürpriz | "Journey to Jerusalem – Kudüs'e Seyahat" | 140 | 3 |

| 22 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Dino and Béatrice | "Putnici" | 86 | 7 |

| 23 | Estonia | Evelin Samuel and Camille | "Diamond of Night" | 90 | 6 |

Spokespersons

editEach country nominated a spokesperson who was responsible for announcing, in English or French, the votes for their respective country.[10] As had been the case since the 1994 contest, the spokespersons were connected via satellite and appeared in vision during the broadcast; spokespersons at the 1999 contest are listed below.[37][56]

- Lithuania – Andrius Tapinas

- Belgium – Sabine De Vos

- Spain – Hugo de Campos

- Croatia – Marko Rašica

- United Kingdom – Colin Berry[44]

- Slovenia – Mira Berginc

- Turkey – Osman Erkan

- Norway – Ragnhild Sælthun Fjørtoft

- Denmark – Kirsten Siggaard

- France – Marie Myriam

- Netherlands – Edsilia Rombley

- Poland – Jan Chojnacki

- Iceland – Áslaug Dóra Eyjólfsdóttir

- Cyprus – Marina Maleni

- Sweden – Pontus Gårdinger[57]

- Portugal – Manuel Luís Goucha

- Ireland – Clare McNamara

- Austria – Dodo Roscic

- Israel – Yoav Ginai

- Malta – Nirvana Azzopardi

- Germany – Renan Demirkan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina – Segmedina Srna

- Estonia – Mart Sander[58]

Detailed voting results

editTelevoting was used to determine the points awarded by all countries, except Lithuania, Turkey, Ireland and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[44] Ireland had intended to use televoting, however technical failures at Telecom Éireann ahead of the voting window meant that the majority of calls were not registered and the country's back-up jury was utilised to determine its points.[59]

The announcement of the results from each country was conducted in the order in which they performed, with the spokespersons announcing their country's points in English or French in ascending order.[10][37] The detailed breakdown of the points awarded by each country is listed in the tables below.

| Voting procedure used: 100% televoting 100% jury vote

|

Total score

|

Lithuania

|

Belgium

|

Spain

|

Croatia

|

United Kingdom

|

Slovenia

|

Turkey

|

Norway

|

Denmark

|

France

|

Netherlands

|

Poland

|

Iceland

|

Cyprus

|

Sweden

|

Portugal

|

Ireland

|

Austria

|

Israel

|

Malta

|

Germany

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina

|

Estonia

| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contestants

|

Lithuania | 13 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Belgium | 38 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Spain | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Croatia | 118 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 3 | |||||

| United Kingdom | 38 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Slovenia | 50 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| Turkey | 21 | 4 | 5 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Norway | 35 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 71 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |||||||||||

| France | 14 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 71 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |||||||||

| Poland | 17 | 7 | 4 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Iceland | 146 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 10 | ||||||

| Cyprus | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweden | 163 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 12 | 12 | |||

| Portugal | 12 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 18 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Austria | 65 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Israel | 93 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| Malta | 32 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 140 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 3 | 10 | 7 | |||||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 86 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Estonia | 90 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 3 | |||||

12 points

editThe below table summarises how the maximum 12 points were awarded from one country to another. The winning country is shown in bold. Germany and Sweden each received the maximum score of 12 points from five countries, with Iceland receiving three sets of 12 points, Croatia and Slovenia receiving two sets each, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, Denmark, Ireland, Netherlands, Portugal and Turkey each receiving one maximum score.[60][61]

| N. | Contestant | Nation(s) giving 12 points |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Germany | Israel, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Turkey |

| Sweden | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Estonia, Malta, Norway, United Kingdom | |

| 3 | Iceland | Cyprus, Denmark, Sweden |

| 2 | Croatia | Slovenia, Spain |

| Slovenia | Croatia, Ireland | |

| 1 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Austria |

| Denmark | Iceland | |

| Ireland | Lithuania | |

| Netherlands | Belgium | |

| Portugal | France | |

| Turkey | Germany |

Broadcasts

editEach participating broadcaster was required to relay live and in full the contest via television. Non-participating EBU member broadcasters were also able to relay the contest as "passive participants"; any passive countries wishing to participate in the following year's event were also required to provide a live broadcast of the contest or a deferred broadcast within 24 hours.[10] Broadcasters were able to send commentators to provide coverage of the contest in their own native language and to relay information about the artists and songs to their viewers. Known details on the broadcasts in each country, including the specific broadcasting stations and commentators, are shown in the tables below.

| Country | Broadcaster | Channel(s) | Commentator(s) | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | SBS | SBS TV[m] | [98] | |

| Falkland Islands | BFBS | BFBS Television[n] | [99] | |

| Faroe Islands | SvF | [100] | ||

| Finland | YLE | TV1 | Jani Juntunen | [101][102] |

| Radio Suomi | Sanna Kojo | [103] | ||

| Radio Vega | [104] | |||

| Greenland | KNR | KNR | [105] | |

| Latvia | LTV | Kārlis Streips | [106][107] | |

| Romania | TVR | TVR 1 | Doina Caramzulescu and Costin Grigore | [108] |

| ROR | Radio România Actualități | Ana Maria Zaharescu | [109] | |

| Russia | ORT | Olga Maksimova and Kolya MacCleod | [110] | |

| Jewish Channel[o] | [111] | |||

| Switzerland | SRG SSR | SF 2 | Sandra Studer | [62][112] |

| TSR 1 | Jean-Marc Richard | [88][73] | ||

| TSI 2 | [88] | |||

| DRS 1[p] | [113] | |||

Other awards

editBarbara Dex Award

editThe Barbara Dex Award, created in 1997 by fansite House of Eurovision, was awarded to the performer deemed to have been the "worst dressed" among the participants.[114] The winner in 1999 was Spain's representative Lydia, as determined by visitors to the House of Eurovision website. This was the first edition of the award to be determined by site visitors, as the winners in 1997 and 1998 had been chosen by the founders of the House of Eurovision site Edwin van Thillo and Rob Paardekam.[115][116][117]

Notes and references

editNotes

edit- ^ On behalf of the German public broadcasting consortium ARD[23]

- ^ Determined by totalling all points awarded in the past five contests and dividing by the number of times that country had participated.[10] 1996 did not count as a participation for countries that didn't qualify from the qualification round.

- ^ a b Despite having the same average score, Sweden ranked higher than Cyprus by virtue of achieving a higher score in the most recent contest.[10]

- ^ a b Despite having the same average score, the Netherlands ranked higher than Germany by virtue of achieving a higher score in the most recent contest.[10]

- ^ a b As Latvia withdrew their participation at a late stage the eliminated country with the highest average points total, Hungary, was offered their place. After declining the offer, the place subsequently passed to Portugal as the country with the next highest average points total.[2]

- ^ a b Despite having the same average score, Finland ranked higher than Slovakia by virtue of achieving a higher score in the most recent contest.[10]

- ^ Although at the 1977 contest each participant was required to perform in the language of the country they represented, Germany and Belgium were granted exceptions as their entries had already been chosen when the rule was reintroduced.[42]

- ^ Additional deferred broadcast on TV5 Europe at 00:05 (CEST)[73]

- ^ Additional live broadcast on RTP Internacional[88]

- ^ Additional live broadcast on TVE Internacional[88]

- ^ Additional live broadcast on TRT Int[94]

- ^ Additional live broadcast on BBC Prime[88]

- ^ Deferred broadcast on 30 May 1999 at 20:30 (AEST)[98]

- ^ Deferred broadcast at 21:00 (FKT)[99]

- ^ Delayed broadcast on 5 December 1999 at 16:00 (NOVT)[111]

- ^ Deferred broadcast at 22:00 (CEST)[113]

References

edit- ^ "Israel – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Jerusalem 1999 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 367–369. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ "The ICC Jerusalem – Venue for the 1999 Eurovision Song Contest". eurosong.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2002. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Horovitz, David (11 May 1998). "Eurovision win by Israeli transsexual causes dispute". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b Sharrock, David (29 May 1999). "Discord at pop's Tower of Babel". The Guardian. Jerusalem, Israel. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. pp. 156–159. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- ^ Walker, Christopher (29 May 1999). "Not all in tune with Euro Song". Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Canada. ProQuest 433482756. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Philips, Alan (29 May 1999). "Armed police ring Eurovision venue". The Daily Telegraph. London, United Kingdom. ProQuest 317203755. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Rules of the 44th Eurovision Song Contest, 1999" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Rules of the 43rd Eurovision Song Contest, 1998" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "13 years ago today: Sweden wins the contest". European Broadcasting Union. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Sigurðsson, Hlynur (11 March 2022). "Get to know the Söngvakeppnin finalists". ESCXtra. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Drejer, Dennis (17 February 2001). "Vinderen og de evige toere" [The winner and the eternal runners-up]. B.T. (in Danish). Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Abela, Benjamin (18 February 2022). "'Fly high' – Beloved musician Chris Scicluna passes away". GuideMeMalta.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Ohlin, Susanne (20 July 2012). "Körledaren Gabriel Forss berättar om sin biografi" [Choir director Gabriel Forss talks about his biography] (in Swedish). TV4. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Kristiansen, Wivian Renee (9 December 2015). "Xtra Eurovision Advent Calendar; 9 December". ESCXtra. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Vermeulen, André (2021). Van Canzonissima tot Eurosong: 65 jaar belgische preselecties voor het Eurovisiesongfestival [From Canzonissima to Eurosong: 65 years of Belgian preselections for the Eurovision Song Contest] (in Dutch) (2nd ed.). Leuven, Belgium: Kritak. p. 269. ISBN 978-94-0147-609-6.

Vanessa krijgt vocale steun van vier Nederlandse koorzangeressen onder wie Henriëtte Willems die als Linda Williams in 1981 Nederland op het songfestival vertegenwoordigde met 'Het is een wonder'.

[Vanessa received vocal support from four Dutch choir singers, including Henriëtte Willems, who represented the Netherlands at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1981 as Linda Williams with 'Het is een wonder'.] - ^ "Spot the Backing Singer". BBC. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Participants of Jerusalem 1999". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "44th Eurovision Song Contest" (in French and English). European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 7 March 2001. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 370–378. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ "Alle deutschen ESC-Acts und ihre Titel" [All German ESC acts and their songs]. www.eurovision.de (in German). ARD. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Jordan, Paul (18 September 2016). "Milestone Moments: 1993/4 – The Eurovision Family expands". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Final of Dublin 1994 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Final of Dublin 1995 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Final of Oslo 1996 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Final of Dublin 1997 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Final of Birmingham 1998 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ "The Organisers behind the Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 25 September 2024. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ Jordan, Paul; Smulders, Stijn (10 October 2017). "Christine Marchal-Ortiz: 'I feel so nostalgic about Eurovision'". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 210.

- ^ "Ussishkin Auditorium – Hall Plan" (PDF). International Convention Centre. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest 1999". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 6 March 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Dafna Dekel: 'I wouldn't mind hosting Eurovision again'". European Broadcasting Union. 21 August 2021. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Eurovision Song Contest 1999 (Television programme). Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Broadcasting Authority. 29 May 1999.

- ^ "Sweden in Eurovision heaven". BBC News. 30 May 1999. Archived from the original on 1 October 2002. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b O'Connor 2010, p. 216.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest Israel 1999". Discogs. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest: Israel 1999". MusicBrainz. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ a b Escudero, Victor M. (21 September 2017). "#ThrowbackThursday to 40 years ago: Eurovision 1977". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "In a Nutshell – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 31 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 379–381. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- ^ Egan, John (22 May 2015). "All Kinds of Everything: a history of Eurovision Postcards". ESC Insight. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Kurris, Denis (1 May 2022). "Eurovision 2022: The theme of this year's Eurovision postcards". ESC Plus. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Charlotte Nilsson – Sweden – Jerusalem 1999". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Sweden – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Iceland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Croatia – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Bosnia & Herzegovina – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Barlow, Eve (10 May 2018). "Viva la diva! How Eurovision's Dana International made trans identity mainstream". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Croatia". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 27 November 1999. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "Final of Jerusalem 1999 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ "Eurovision legends to perform at Danish final". European Broadcasting Union. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Dublin 1994 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Thorsson, Leif; Verhage, Martin (2006). Melodifestivalen genom tiderna : de svenska uttagningarna och internationella finalerna [Melodifestivalen through the ages: the Swedish selections and international finals] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Premium Publishing. pp. 274–275. ISBN 91-89136-29-2.

- ^ "Eesti žürii punktid edastab Eurovisioonil Tanel Padar" [The points of the Estonian jury will be announced by Tanel Padar at Eurovision] (in Estonian). Muusika Planeet. 14 May 2022. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Kavanagh, Aoife (31 May 1999). "Standby Jury Ensures Ireland Votes". RTÉ News. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ a b c "Results of the Final of Jerusalem 1999". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Eurovision Song Contest 1999 – Scoreboard". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Radio TV Samstag" [Radio TV Saturday]. Freiburger Nachrichten (in German). Fribourg, Switzerland. 29 May 1999. p. 14. Retrieved 26 June 2022 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Song Contest : Andi Knoll ratlos wie noch nie" [Eurovision: Andi Knoll at a loss like never before]. Österreich (in German). 17 May 2013. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Song Contest mit Stermann & Grissemann" [Eurovision with Stermann & Grissemann] (in German). ORF. 1 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Radio en televisie" [Radio and television]. Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant (in Dutch). 29 May 1999. p. 38. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ "VRT zet grote kanonnen in" [VRT deploy the big guns]. De Standaard (in Dutch). 17 April 2002. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Samstag 29. Mai | Samedi 29 mai" [Saturday 29 May]. Télé-Revue (in German, French, and Luxembourgish). 27 May 1999. p. 14–19. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Prijenos iz Jeruzalema: Eurosong '99" [Broadcast from Jerusalem: Eurosong '99]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Split, Croatia. 29 May 1999. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "TV επιλογεσ" [TV choices]. Charavgi (in Greek). Nicosia, Cyprus. 29 May 1999. p. 16. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024 – via Press and Information Office.

- ^ "Alle tiders programoversigter – Lørdag den 29. maj 1999" [All-time programme overviews – Saturday 29th May 1999] (in Danish). DR. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "TV – Laupäev 29. mai" [TV – Saturday 29 May]. Sõnumileht (in Estonian). 29 May 1999. pp. 29–30. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via DIGAR Eesti artiklid.

- ^ Hõbemägi, Priit (30 May 1999). "Reikop rõdu viimases reas" [Reikop in the last row of the balcony]. Õhtuleht (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Télévision – samedi" [Television – Saturday]. La Liberté (in French). Fribourg, Switzerland. 29 May 1999. p. 44. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Télévision" [Television]. L'Est éclair (in French). Saint-André-les-Vergers, France. 29 May 1999. p. 31. Retrieved 23 September 2024 – via Aube en Champagne.

- ^ "Sjónvarp | Útvarp" [Television | Radio]. Morgunblaðið Dagskrá (in Icelandic). Reykjavík, Iceland. 26 May 1999. pp. 10, 33. Retrieved 29 May 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ "Television – Saturday". The Irish Times Weekend. 29 May 1999. p. 22. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Murphy, Eoin (12 May 2019). "Pat Kenny's stance on Israel hosting the Eurovision might surprise you". extra.ie. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Saturday Radio". The Irish Times Weekend. 29 May 1999. p. 21. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "على الشاشة الصغيرة - برامج التلفزيون الاسرائيلي - السبت ٢٩\٥\٩٩ - القناة الأولى" [On the small screen – Israeli television programmes – Saturday 29/5/99 – Channel One]. Al-Ittihad (in Arabic). Haifa, Israel. 28 May 1999. p. 23. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023 – via National Library of Israel.

- ^ "TV – sobota 29 maja" [TV – Saturday 29 May] (PDF). Kurier Wileński (in Polish). Vilnius, Lithuania. 29 May 1999. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022 – via Polonijna Biblioteka Cyfrowa.

- ^ Granger, Anthony (5 May 2019). "Lithuania: Darius Užkuraitis Enters Eurovision Commentary Booth For Twenty-Second Contest". Eurovoix. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Television". Times of Malta. 29 May 1999. p. 31.

- ^ "Songfestival rechtstreeks op TV2" [Eurovision live on TV2]. Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant (in Dutch). 28 May 1998. p. 9. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Radio og TV" [Radio and TV]. Dagsavisen (in Norwegian). 29 May 1999. pp. 53–55. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Norway.

- ^ "Norgeskanalen NRK P1 – Kjøreplan lørdag 29. mai 1999" [The Norwegian channel NRK P1 – Schedule Saturday 29 May 1999] (in Norwegian). NRK. 29 May 1999. p. 14. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via National Library of Norway. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- ^ "Telewizja – sobota" [Television – Saturday]. Codziennik (in Polish). Gdańsk, Poland. 28–29 May 1999. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 31 October 2024 – via Baltic Digital Library.

- ^ Erling, Barbara (12 May 2022). "Artur Orzech zapowiada, że skomentuje Eurowizję, ale tym razem na Instagramie" [Artur Orzech announces that he will comment on Eurovision, but this time on Instagram] (in Polish). Press. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Samedi 29 mai" [Saturday 29 May]. TV8 (in French). Zofingen, Switzerland: Ringier. 27 May 1999. pp. 20–25. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- ^ "Programa da televisão" [Television programme]. A Comarca de Arganil (in Portuguese). 27 May 1999. p. 8. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Costa, Nelson (12 April 2014). "Luciana Abreu, Rui Unas e Mastiksoul em 'Dança do Campeão'" [Luciana Abreu, Rui Unas and Mastiksoul in 'Dança do Campeão']. escportugal.pt (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "televizija in radio – sobota" [television and radio – saturday]. Delo (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia. 29 May 1999. p. 28. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "Televisión" [Television]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 29 May 1999. p. 8. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "TV & Radio". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden. 29 May 1999. p. 39.

- ^ a b "TV Programları" [TV Programme]. Cumhuriyet (in Turkish). Istanbul, Turkey. 29 May 1999. p. 16. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Eurovision'da final gecesi" [Eurovision final night]. Milliyet (in Turkish). Istanbul, Turkey. 29 May 1999. p. 30. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ "The Eurovision Song Contest – BBC One". Radio Times. 29 May 1999. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ "The Eurovision Song Contest – BBC Radio 2". Radio Times. 29 May 1999. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ a b "On TV – Eurovision". The Australian Jewish News. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. 28 May 1999. p. 23. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022 – via National Library of Israel.

- ^ a b "Your BFBS Television programmes" (PDF). Penguin News. Stanley, Falkland Islands. 29 May 1999. Retrieved 25 September 2024 – via Jane Cameron National Archives.

- ^ "Sjónvarpsskráin SvF – Leygardagin 29. mai" [SvF TV schedule – Saturday 29 May]. Oyggjatíðindi (in Faroese and Danish). Hoyvík, Faroe Islands. 28 May 1999. p. 12. Retrieved 15 July 2024 – via Infomedia.

- ^ Sirpa, Pääkkönen (29 May 1999). "Osallistujat saavat nyt valita euroviisukielen" [Participants can now choose a Eurovision language]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "TV1". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland. 29 May 1999. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ "Radio Suomi". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland. 29 May 1999. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ "Radio Vega". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland. 29 May 1999. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ "KNR Aallakaatitassat – Arfininngorneq 29. maj | KNR Programmer – Lørdag 29. maj" [KNR Programmes – Saturday 29 May]. Atuagagdliutit (in Kalaallisut and Danish). Nuuk, Greenland. 27 May 1999. pp. 26–27. Retrieved 15 July 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ "Eirovīzijas Dziesmu konkursa Nacionālā atlase" [National selection for the Eurovision Song Contest] (in Latvian). Digitalizētie Video un Audio (DIVA). Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Streips kā dalībnieks debitē 'Eirovīzijā'" [Streips debuts as a Eurovision participant] (in Latvian). Delfi. 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Sâmbătă 29 mai 1999" [Saturday 29 May 1999]. Panoramic TV. pp. 8–9.

- ^ "Sâmbătă 29 mai" [Saturday 29 May]. Radio România (in Romanian). p. 8.

- ^ "Понедельник, 14 июня" [Monday 14 June]. Orenburgskaya Nedelya (in Russian). No. 24. 10 June 1999. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2023 – via Integrum (Russian news database).

- ^ a b "TV. Воскресенье, 5 декабря" [TV. Sunday 5 December] (PDF). Sovetskaya Sibir (in Russian). Novosibirsk, Russia. 26 November 1999. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "Musik am Bildschirm: Stomp, Grandprix, Strauss und Orpheus" [Music on the screen: Stomp, Eurovision, Strauss and Orpheus]. Freiburger Nachrichten (in German). Fribourg, Switzerland. 29 May 1999. p. 14. Retrieved 21 May 2023 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b "Radio". Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Zurich, Switzerland. 29 May 1999. p. 75. Retrieved 29 October 2024 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Backer, Stina (25 May 2012). "Forgettable song, memorable outfit: The crazy clothes of Eurovision". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Barbara Dex Award – All winners". songfestival.be. 30 May 2021. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Philips, Roel (25 May 2005). "Martin Vucic wins Barbara Dex Award". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "About Us". The House of Eurovision. Archived from the original on 15 April 2001. Retrieved 25 June 2022.