This article's lead section may be too long. (December 2023) |

Nusaybin (pronounced [nuˈsajbin]) is a municipality and district of Mardin Province, Turkey.[2] Its area is 1,079 km2,[3] and its population is 115,586 (2022).[1] The city is populated by Kurds of different tribal affiliation.[4]

Nusaybin | |

|---|---|

District and municipality | |

Clockwise from top: Sakarya Caddesi and Barsı Parkı in central Nusaybin, Nusaybin city hall, the neighboring border zone to Syria, Church of Saint Jacob of Nisibis, Zeynel Abidin Mosque | |

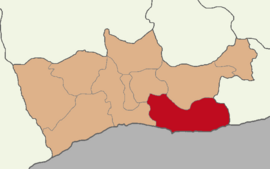

Map showing Nusaybin District in Mardin Province | |

| Coordinates: 37°04′30″N 41°12′55″E / 37.07500°N 41.21528°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Mardin |

| Government | |

| • Kaymakam | Ercan Kayabaşı |

Area | 1,079 km2 (417 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | 115,586 |

| • Density | 110/km2 (280/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 47300 |

| Area code | 0482 |

| Website | www www |

Nusaybin is separated from the larger Kurdish-majority city of Qamishli by the Syria–Turkey border.[5][6]

The city is at the foot of the Mount Izla escarpment at the southern edge of the Tur Abdin hills, standing on the banks of the Jaghjagh River (Turkish: Çağçağ), the ancient Mygdonius (Ancient Greek: Μυγδόνιος).[7] The city existed in the Assyrian Empire and is recorded in Akkadian inscriptions as Naṣibīna.[7][8] Having been part of the Achaemenid Empire, in the Hellenistic period the settlement was re-founded as a polis named "Antioch on the Mygdonius" by the Seleucid dynasty after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[7] A part of first the Roman Republic and then the Roman Empire, the city (Latin: Nisibis; Ancient Greek: Νίσιβις) was mainly Syriac-speaking, and control of it was contested between the Kingdom of Armenia, the Romans, and the Parthian Empire.[7] After a peace treaty contracted between the Sasanian Empire and the Romans in 298 and enduring until 337, Nisibis was capital of Roman Mesopotamia and the seat of its governor (Latin: dux mesopotamiae). Jacob of Nisibis, the city's first known bishop, constructed its first cathedral between 313 and 320.[7] Nisibis was a focus of international trade, and according to the Greek history of Peter the Patrician, the primary point of contact between Roman and Persian empires.[7]

Nisibis was besieged three times by the Sasanian army under Shapur II (r. 309–379) in the first half of the 4th century; each time, the city's fortifications held.[7] The Syriac poet Ephrem the Syrian witnessed all three sieges, and praised Nisibis's successive bishops for their contributions to the defences in his Carmina Nisibena, 'song of Nisibis', while the Roman caesar Julian (r. 355–363) described the third siege in his panegyric to his senior co-emperor, the augustus Constantius II (r. 337–361).[7] The Roman soldier and Latin historian Ammianus Marcellinus described Nisibis, fortified with walls, towers, and a citadel, as "the strongest bulwark of the Orient".[7]

After the defeat of the Romans in Julian's Persian War, Julian's successor Jovian (r. 363–364) was forced to cede the five Transtigritine provinces to the Persians, including Nisibis.[7] The city was evacuated and its citizens forced to migrate to Amida (Diyarbakır) – which was expanded to accommodate them – and to Edessa (Urfa). According to the Latin historian Eutropius, the cession of Nisibis was supposed to last 120 years.[7] Nisibis remained a major entrepôt; one of only three such cities of commercial exchange allowed by Roman law promulgated in 408/9.[7] However, despite several Roman attempts to recapture Nisibis through the remainder of the Roman–Persian Wars and the construction of nearby Dara to defend against Persian attack, Nisibis was not returned to Roman control before it was conquered in 639 by the Rashidun Caliphate during the Muslim conquest of the Levant.[7]

Under Sasanian rule and after, Nisibis was a major centre of the Christian Church, and the bishop of Nisibis attended the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon convened in 410 by the emperor Yazdegerd I (r. 399–420).[7] As a result of this council, the Church of the East was set up, and the bishop of Nisibis became the metropolitan bishop of the five erstwhile Transtigritine provinces.[7] Narsai, formerly a theologian at the School of Edessa, founded the famous School of Nisibis with the bishop, Barsauma, in the 470s.[7] When the Roman emperor Zeno (r. 474–491) closed the School of Edessa in 489, the scholars migrated to Nisibis's school and established the city as the foremost centre of Christian thought in the Church of the East.[7] According to the Damascene monk John Moschus, the city's cathedral had five doors in the 7th century, and the monastic and later bishop of Harran, Symeon of the Olives, was recorded as having renewed several ecclesiastical buildings in the early period of Arab rule.[7] The monasteries of the nearby Tur Abdin, led by the reforms of Abraham the Great of Kashkar, founder of the "Great Monastery" of Mount Izla, underwent substantial revival in the years after the Muslim conquest.[7] However, besides the baptistery known as the Church of Saint Jacob (Mar Ya‘qub) and built in 359 by bishop Vologeses, little remains of ancient Nisibis, probably because of ruinous earthquake in 717.[7] Archaeological excavations were conducted in the vicinity of the 4th-century baptistery in the early 21st century, revealing various buildings including the 4th-century cathedral.[7]

History

editAntiquity

editFirst mentioned in 901 BCE, Naṣibīna was an Aramean kingdom captured by the Assyrian king Adad-Nirari II in 896.[9] By 852 BCE, Naṣibīna had been fully annexed to the Neo-Assyrian Empire and appeared in the Assyrian Eponym List as the seat of an Assyrian provincial governor named Shamash-Abua.[10]

It was under Babylonian control until 536 BCE, when it fell to the Achaemenid Persians, and remained so until taken by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE.

Hellenistic period

editThe Seleucids re-founded the city as Antiochia Mygdonia (Greek: Ἀντιόχεια τῆς Μυγδονίας), mentioned for the first time in Polybius' description of the march of Antiochus III the Great against Molon (Polybius, V, 51). The Greek historian Plutarch suggested that the city was populated by descendants of Spartans. Around the 1st century CE, Nisibis (Hebrew: נציבין, romanized: Netzivin) was the home of Judah ben Bethera, who founded a famous yeshiva there.[11]

In 67 BCE, during Rome's first war with Armenia, the Roman general Lucullus took Nisibis (Armenian: Մծբին, romanized: Mtsbin) from the brother of Tigranes.[12]

Like many other cities in the marches where Roman and Parthian powers confronted one another, Nisibis was often taken and retaken. In 115 CE, it was captured by the Roman Emperor Trajan, for which he gained the name of Parthicus,[13] then lost to and regained from the Jews during the Diaspora Revolt. After the Romans again lost the city in 194, it was once more conquered by Septimius Severus, who made it his headquarters and re-established a colony there.[14] The last battle between Rome and Parthia was fought in the vicinity of the city in 217.[15]

Late Antiquity

editWith the fresh energy of the new Sassanid dynasty, Shapur I conquered Nisibis, was driven out, and returned in the 260s. In 298, by a treaty with Narseh, the province of Nisibis was acquired by the Roman Empire.

During the Roman–Persian Wars (337–363 CE) Nisibis was unsuccessfully besieged by the Sassanid Empire thrice, in 337, 346 and 350. According to the Expositio totius mundi et gentium bronze and iron were forbidden to be exported to the Persians, but for other goods, Nisibis was the site of substantial trade across the Roman–Persian frontier.[7]

Upon the death of Constantine the Great in 337 CE, the Sassanid Shah Shapur II marched against Roman held Nisibis with a vast army composed of cavalry, infantry and elephants. His combat engineers raised siege works, including towers, so his archers could rain down arrows at the defenders. They also undermined the walls, dammed the Mygdonius River and constructed dikes to direct the river against the walls. On the seventieth day of the siege, the water was released and the torrent struck the walls; entire sections of the city walls collapsed. The water passed through the city and knocked down a section of the opposite wall as well. The Persians were unable to assault the city because the approaches to the breaches were impassable due to floodwater, mud and debris. The soldiers and citizens inside the city worked all night and by dawn the breaches were closed with makeshift barriers. Shapur's assault troops attacked the breaches, but their assault was repulsed. A few days later the Persian lifted the siege.[16]

Nisibis was besieged a second time in 346 CE. The details of the second siege have not survived. Shapur besieged the city for seventy-eight days and then lifted the siege.[17]

In 350 CE, while the Roman Emperor Constantius II was engaged in a civil war against the usurper Magnentius in the West, the Persians invaded and laid siege to Nisibis for the third time. The siege lasted between 100 and 160 days. The Persian engineers tried several innovative siege technics; using the River Mygdonius to bring down a section of the walls, and creating a lake around the city and using boats with siege engines to bring down another section. Unlike the first siege, as the walls fell, Persian assault troops immediately entered the breaches supported by war elephants. Despite all this they failed to break through the breaches and the attack stalled. The Romans, experts at close-quarter combat, and supported by arrows and bolts from the walls and towers checked the assault and a sortie from one of the gates forced the Persians to withdraw. Shortly after the Persian Army, suffering heavy casualties from combat and disease, lifted the siege and withdrew.[18]

The Roman historian of the 4th century, Ammianus Marcellinus, gained his first practical experience of warfare as a young man at Nisibis under the magister equitum, Ursicinus. From 360 to 363, Nisibis was the camp of Legio I Parthica. Because of its strategic importance on the Persian border, Nisibis was heavily fortified. Ammianus lovingly calls Nisibis the "impregnable city" (urbs inexpugnabilis) and "bulwark of the provinces" (murus provinciarum).

Sozomen writes that when the inhabitants of Nisibis asked for help because the Persians were about to invade the Roman territories and attack them, Emperor Julian refused to assist them because they were Christianized, and he told them that he would not help them if they did not return to paganism.[19]

In 363 Nisibis was ceded to the Sassanian Empire after the defeat of Julian. Before that time the population of the town was forced by the Roman authorities to leave Nisibis and move to Amida. Emperor Jovian allowed them only three days for the evacuation. Historian Ammianus Marcellinus was again an eyewitness and condemns Emperor Jovian for giving up the fortified town without a fight. Marcellinus' point-of-view is certainly in line with contemporary Roman public opinion.

According to Al-Tabari, some 12,000 Persians of good lineage from Istakhr, Isfahan, and other regions settled at Nisibis in the fourth century, and their descendants were still there at the beginning of the seventh century.[20]

The School of Nisibis, founded at the introduction of Christianity into the city by ethnic Assyrians of the Assyrian Church of the East,[21] was closed when the province was ceded to the Persians. Ephrem the Syrian, an Assyrian poet, commentator, preacher and defender of orthodoxy, joined the general exodus of Christians and re-established the school on more securely Roman soil at Edessa. In the fifth century, the school became a center of Nestorian Christianity, and was closed down by Archbishop Cyrus in 489. The expelled masters and pupils withdrew once more, back to Nisibis, under the care of Barsauma, who had been trained at Edessa, under the patronage of Narses, who established the statutes of the new school. Those that have been discovered and published belong to Osee, the successor of Barsauma in the See of Nisibis, and bear the date 496; they must be substantially the same as those of 489. In 590, they were again modified. The monastery school was under a superior called Rabban ("master"), a title also given to the instructors. The administration was confided to a major-domo, who was steward, prefect of discipline and librarian, but under the supervision of a council. Unlike the Jacobite schools, devoted chiefly to profane studies, the School of Nisibis was above all a school of theology. The two chief masters were the instructors in reading and in the interpretation of Holy Scripture, explained chiefly with the aid of Theodore of Mopsuestia. The free course of studies lasted three years, the students providing for their own support. During their sojourn at the university, masters and students led a monastic life under somewhat special conditions. The school had a tribunal and enjoyed the right of acquiring all sorts of property. Its rich library possessed a most beautiful collection of Nestorian works; from its remains Ebed-Jesus, Bishop of Nisibis in the 14th century, composed his celebrated catalogue of ecclesiastical writers. The disorders and dissensions, which arose in the sixth century in the school of Nisibis, favoured the development of its rivals, especially that of Seleucia; however, it did not really begin to decline until after the foundation of the School of Baghdad (832). Notable people associated with the school include its founder Narses; Abraham, his nephew and successor; Abraham of Kashgar, the restorer of monastic life; and Archbishop Elijah of Nisibis.

As a fortified frontier city, Nisibis played a major role in the Roman-Persian Wars. It became the capital of the newly created province of Mesopotamia after Diocletian's organization of the eastern Roman frontier. It became known as the "Shield of the Empire" after a successful resistance in 337–350. The city changed hands several times, and once in Sasanian hands, Nisibis was the base of operations against the Romans. The city was also one of the main crossing points for merchants, although elaborate counter-espionage safeguards were also in place.[22]

Islamic period

editThe city was taken without resistance by the forces of the Rashidun Caliphate under Umar in 639 or 640. Under early Islamic rule, the city served as a local administrative centre. In 717, it was struck by an earthquake and in 927 it was raided by the Qarmatians. Nisibis was captured in 942 by the Byzantine Empire but was subsequently recaptured by the Hamdanid dynasty. It was attacked by the Byzantines once again in 972. Following the Hamdanids, the city was administered by the Marwanids and the Uqaylids. From the middle of the 11th century onwards, it was subjected to Turkish raids and being threatened by the County of Edessa, being attacked and damaged by Seljuq forces under Tughril in 1043. The city nevertheless remained an important centre of commerce and transport.[23]

In 1120, it was captured by the Artuqids under Necmeddin Ilgazi, followed by the Zengids and Ayyubids. The city is described as a very prosperous one by the period's Arab geographers and historians, with imposing baths, walls, lavish houses, a bridge and a hospital. In 1230, the city was invaded by the Mongol Empire. Mongol sovereignty was followed by that of the Ag Qoyunlu, Kara Koyunlu and Safavids. In 1515, it was taken by the Ottoman Empire under Selim I thanks to the efforts of Idris Bitlisi.[23]

Modern history

editOn the eve of World War I, Nusaybin had a Christian community of 2000, along with a Jewish population of 600.[24] A massacre of Christians took place in August 1915, after which the Christian community of Nusaybin diminished to 1200. Syrian Jacobites, Chaldean Catholics, Protestants, and Armenians were targeted.[25][26][27][28]

As agreed upon by the governments of France and the new Republic of Turkey in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, the Turkey-Syria border would follow the line of the Baghdad Railway until Nusaybin, after which it would follow the path of a Roman road leading to Cizre.[29] After the establishment of the French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon, Nusaybin lost over 60% of its population to the settlements there, most prominently Qamishli.[30]

Nusaybin was a place on the transit routes of Syrian Jews leaving the country after the 1948 formation of Israel and the subsequent Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries. Upon reaching Turkey, after a route that took them through Aleppo and the Jazira sometimes with the help of Bedouin smugglers, most headed for Israel.[31] There had been a large Jewish community in Nisbis since antiquity, many of whom moved to Qamishli in the early 20th century for economic reasons. A synagogue in Jerusalem practises the Nisibis and Qamishli rites today.

21st century

editNusaybin made headlines in 2006 when villagers near Kuru uncovered a mass grave, suspected of belonging to Ottoman Armenians and Assyrians killed during the Armenian and Assyrian genocides.[32] Swedish historian David Gaunt visited the site to investigate its origins, but left after finding evidence of tampering.[33][34][35] Gaunt, who has studied 150 massacres carried out in the summer of 1915 in Mardin, said that the Committee of Union and Progress's governor for Mardin, Halil Edip, had likely ordered the massacre on 14 June 1915, leaving 150 Armenians and 120 Assyrians dead. The settlement was then known as Dara (now Oğuz). Gaunt added that the death squad, named El-Hamşin (meaning "fifty men"), was headed by officer Refik Nizamettin Kaddur. The president of the Turkish Historical Society, Yusuf Halaçoğlu, following the Turkish government's policy of Armenian genocide denial, said that the remains dated back to Roman times.[36] Özgür Gündem reported that the Turkish military and police pressed the Turkish media not to report the discovery.[37]

The Turkish Interior Ministry looked into dissolving Nusaybin city council in 2012 after it decided to use Arabic, Armenian, Aramaic, and Kurmanji on signposts in the town, in addition to the Turkish language.[38]

Tensions and violence

editIn November 2013, Nusaybin's mayor, Ayşe Gökkan, commenced a hunger strike to protest against the construction of a wall between Nusaybin and the neighboring Kurdish-majority city of Qamishli in Syria. Construction of the wall stopped as a result of this and other protests.[39]

On 13 November 2015, the town was placed under a curfew by the Turkish government, and Ali Atalan and Gülser Yıldırım, two elected members of the Grand National Assembly from the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), began a hunger strike in protest. Two civilians and ten PKK fighters were killed by security forces in the ensuing unrest.[40] By March 2016, PKK forces controlled about half of Nusaybin according to Al-Masdar News[41] and the YPS controlled "much" of it, according to The Independent.[42] The Turkish state imposed eight successive curfews over several months and employed the use of heavy weapons in defeating the Kurdish militants, resulting in large swathes of Nusaybin being destroyed.[43] 61 members of the security forces had been killed by May 2016.[44] By 9 April, 60,000 residents of the city had been displaced, yet 30,000 civilians remained in the city, including in the six neighborhoods where fighting continued.[45] YPS reportedly had 700–800 militants in the city,[45] of which the Turkish army claimed that 325 were "neutralised" by 4 May.[46] A curfew was in place between 14 March and 25 July in the majority of the town.[47] After the fighting ended in a Turkish Army victory, in late September 2016 the Turkish government began demolishing a quarter of the city's residential buildings. This rendered 30,000 citizens homeless and caused a mass evacuation of tens of thousands of residents to neighboring towns and villages. Over 6,000 houses were bulldozed. After demolition was completed in March 2017, over one hundred apartment towers were built. The Turkish government offered to compensate homeowners at 12% of the value of their destroyed houses if they agreed to certain relocation conditions.[48]

Economy

editAs a result of Turkish government policy to close all border crossings with the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the city's border with Syria (i.e. the large Syrian city of Qamishli) has been closed, with claims that the cessation in smuggling has led to a 90% rise in unemployment in the city.[49]

Transportation

editNusaybin is served by the E90 roadway and other roads to surrounding towns. The Nusaybin Railway Station is served by two daily trains. The closest airport is Qamishli Airport five kilometers to the south, in Qamishli in Syria. The closest Turkish airport is Mardin Airport, 55 kilometers northwest of Nusaybin.

Geography

editNusaybin is on the north side of the Syria-Turkey border, which divides it from the city of Qamishli. The Jaghjagh River flows through both cities. The Nusaybin side of the border has a minefield, with a total of some 600,000 landmines having been set by the Turkish Armed Forces since the 1950s. Located to the east is Mount Judi, which people (including Muslims) consider to be the place where the ark of Nuh or Noah (who is regarded as a Nabi or Prophet in Abrahamic religions) came to rest.

Composition

editThere are 84 neighbourhoods in Nusaybin District.[50] Fifteen of these (8 Mart, Abdulkadirpaşa, Barış, Devrim, Dicle, Fırat, Gırnavas, İpekyolu, Kışla, Mor-Yakup, Selahattin Eyyübi, Yenişehir, Yenituran and Zeynelabidin) form the central town (merkez) of Nusaybin.[51]

- 8. Mart

- Abdulkadirpaşa

- Acıkköy (Bamidê)

- Açıkyol (Aferî)

- Akağıl (Derzandik)

- Akarsu (Stîlîtê)

- Akçatarla (Dal)

- Bahçebaşı (Bawernê)

- Bakacık (Kinikê)

- Balaban (Birêgiriya)

- Barış

- Beylik (Bakisyan)

- Büyükkardeş (Cinata Miho)

- Çağlar (Şanîşê)

- Çalıköy (Çalê)

- Çatalözü (Gundikê Xêlid)

- Çiğdem (Giremara)

- Çilesiz (Mezra Mihoka)

- Çölova (Menderê)

- Dağiçi (Harabemişke)

- Dallıağaç (Herbê)

- Değirmencik (Qolika)

- Demirtepe (Girhesin)

- Devrim

- Dibek (Badip)

- Dicle

- Dirim (Şabanê)

- Doğanlı (Talat)

- Doğuş (Qûzo)

- Durakbaşı (Qesra)

- Duruca (Kertwin)

- Düzce (Sirinçk)

- Eskihisar (Marinê)

- Eskimağara (Zivingê)

- Eskiyol (Cuva)

- Fırat

- Girmeli (Girmira)

- Gırnavas

- Görentepe (Bizgur)

- Günebakan (Zorava)

- Güneli (Geliyê Sora)

- Günyurdu (Marbobo), (Merbabê)

- Gürün (Gurinê)

- Güvenli (Xirbeka)

- Hasantepe (Tilhasan)

- Heybeyi (Dêrcemê)

- İkiztepe (Têzxerab)

- Ilkadım (Habisê)

- İpekyolu

- Kalecik (Kelehê, Keleha Bûnûsra)

- Kaleli (Efşê)

- Kantar (Qenter)

- Karacaköy (Xerabê Reşik)

- Kayadibi (Mendikan)

- Kışla

- Kocadağ (Gelîye Pîra)

- Küçükkardeş (Cinata His)

- Kuruköy (Xerabê Bava)

- Kuyular (Cibilgrav)

- Mor-Yakup

- Nergizli (Nergizlokê)

- Odabaşı (Igunduke d-'ito), Gundik Şukrî)

- Pazarköy (Bazar)

- Selahattin Eyyübi

- Sınırtepe (Aznavur)

- Söğütlü (Girêbiya)

- Taşköy (ʼArboʼ)

- Tekağaç (Mişavil)

- Tepealtı (Tel Yaqub)

- Tepeören (Xirbêzil)

- Tepeüstü (Tilminar)

- Turgutköy (Kemina)

- Üçköy (Arkaḥ)

- Üçyol (Sederi)

- Yandere (Hatxê)

- Yavruköy (Kurke)

- Yazyurdu (Qesra Belek)

- Yenişehir

- Yenituran

- Yerköy (Binerdka)

- Yeşilkent

- Yolbilen (Erbet)

- Yolindi (Cibiltînê)

- Zeynelabidin

Climate

editNusaybin has a semi-arid climate with extremely hot summers and cool winters. Rainfall is generally sparse.

| Climate data for Nusaybin | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11 (52) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

22 (72) |

30 (86) |

37 (99) |

41 (106) |

40 (104) |

35 (95) |

28 (82) |

20 (68) |

13 (55) |

26 (78) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6 (43) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

22 (72) |

28 (82) |

32 (90) |

31 (88) |

27 (81) |

21 (70) |

13 (55) |

8 (46) |

19 (65) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3 (37) |

4 (39) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

20 (68) |

16 (61) |

9 (48) |

5 (41) |

13 (56) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51 (2.0) |

30 (1.2) |

35 (1.4) |

26 (1.0) |

16 (0.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

12 (0.5) |

19 (0.7) |

34 (1.3) |

223 (8.7) |

| Average rainy days | 8 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 41 |

| Source: Weather2[52] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editNusaybin is predominantly ethnically Kurdish. The city's people have historically close ties with those of neighboring Qamishli, and cross-border marriages are a common practice.[53][54] The city also contains a minority Arab population.[55]

In early 20th century, Nusaybin was composed mostly of Arabs who came from Mardin, roughly 500 Jews, and some Assyrians, totaling to 2000 people. Likewise, Mark Sykes recorded Nusaybin as a town inhabited by Chaldeans, Arabs, and Jews.[56] The town was largely Arabic-speaking such that Kurdish families settling in the town eventually learned Arabic. The ethnic and linguistic demographics changed after mid-century. Jews migrated to Israel, and Assyrian population substantially decreased. After dense Kurdish migration in late 20th century, Nusaybin became a largely Kurdish-speaking and Kurdish town.[57]

| Turkish | Arabic | Kurdish | Circassian | Armenian | Unknown or other languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,024 | 1,109 | 9,604 | – | – | 536 |

| Muslim | Christian | Jewish | Unknown or other religion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11,212 | 385 | 392 | 282 |

A very small Assyrian population remains in the city; what remained of the Assyrian population emigrated during the height of the Kurdish-Turkish conflict in the 1990s and as a result of the resumption of the conflict in 2016, only one Assyrian family reportedly remained in the city.[59][60]

Christianity

editNisibis (Syriac: ܢܨܝܒܝܢ, Nṣibin, later Syriac ܨܘܒܐ, Ṣōbā) had an Assyrian Christian bishop from 300, founded by Babu (died 309). Shapur II besieged the city in 338, 346, and 350, when St Jacob or James of Nisibis, Babu's successor, was its bishop. Nisibis was the home of Ephrem the Syrian, who remained until its surrender to the Sassanid Persians by Roman Emperor Jovian in 363. The bishop of Nisibis was the Metropolitan Archbishop of the ecclesiastical province of Bit-Arbaye. By 410, it had six suffragan sees and as early as the middle of the 5th century was the most important episcopal see of the Church of the East after Seleucia-Ctesiphon. Many of its Nestorian or Assyrian Church of the East and Jacobite bishops were renowned for their writings, including Barsumas, Osee, Narses, Jesusyab and Ebed-Jesus. The Roman Catholic Church has defined titular archbishoprics of Nisibis, for various rites – one Latin and four Eastern Catholic for particular churches sui iuris, notably the Chaldean Catholic Church and the Maronite Catholic Church.[61]

When the Syriac Catholic Eparchy of Hassaké was promoted to archiepiscopal rank, it added Nisibi to its name, becoming the Syriac Catholic Archeparchy of Hassaké-Nisibi (not Metropolitan, directly dependent on the Syriac Catholic Patriarch of Antioch).

Latin titular see

editEstablished in the 18th century as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Romans). It has been vacant for several decades, having previously had the following incumbents, all of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank:

- Giambattista Braschi (1724.12.20 – 1736.11.24)

- José Calzado López (Bolaños de Calatrava, 17/04/1680 – Madrid, 7/04/1761) Discalced Franciscans (O.F.M. Disc.) (1738.11.24 – 1761.04.07)

- Cesare Brancadoro (1789.10.20 – 1800.08.11) (later Cardinal)*

- Lorenzo Caleppi (1801.02.23 – 1816.03.08) (later Cardinal)*

- Vincenzo Macchi (1818.10.02 – 1826.10.02)(later Cardinal)*

- Carlo Luigi Morichini (1845.04.21 – 1852.03.15) (later Cardinal)*

- Vincenzo Tizzani, C.R.L. (1855.03.26 – 1886.01.15) (later Patriarch)*

- Johann Gabriel Léon Louis Meurin, Jesuits (S.J.) (1887.09.15 – 1887.09.27)

- Giuseppe Giusti (1891.12.14 – 1897.03.31)

- Federico Pizza (1897.04.19 – 1909.03.28)

- Francis McCormack (1909.06.21 – 1909.11.14)

- Joseph Petrelli (1915.03.30 – 1962.04.29)

- José de la Cruz Turcios y Barahona, Salesians (S.D.B.) (1962.05.18 – 1968.07.18)

Armenian Catholic titular see

editEstablished as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Armenians) in circa 1910. It was suppressed in 1933, having had a single incumbent, of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank :

- Gregorio Govrik, Mechitarists (C.A.M.) (1910.05.07 – 1931.01.26)

Chaldean Catholic titular see

editEstablished as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Chaldeans) in the late 19th century, suppressed in 1927, restored in 1970. It has had the following incumbents, all of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank :

- Giuseppe Elis Khayatt (22 April 1895 – 13 April 1900)

- Hormisdas Etienne Djibri (30 November 1902 – 31 August 1917)

- Thomas Michel Bidawid (24 August 1970 – 20 March 1971)

- Gabriel Koda (14 December 1977 – February 1992)

- Jacques Ishaq (21 December 2005 – 22 June 2023), Curial Bishop emeritus of the Chaldean Catholic Patriarchate of Babylon

- George Koovakad (25 October 2024 – )[62]

Maronite titular see

editEstablished as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Maronites) in 1960. It is vacant, having had a single incumbent of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank:

- Pietro Sfair (1960.03.11 – 1974.05.18)

Notable people

edit- Ephraim the Syrian (4th century), Christian Saint was native of Nisibis (modern Nusaybin)

- Musa Anter (1920-1992), Kurdish writer, journalist and intellectual

- Gülser Yıldırım (1963*), Politician

- Mithat Sancar (1963*), professor of public and constitutional law, columnist and translator

- Sara Kaya (1970*), Politician

- Ferhad Ayaz (1994*), Footballer

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Büyükşehir İlçe Belediyesi, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "İl ve İlçe Yüz ölçümleri". General Directorate of Mapping. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Tan, Altan (2018). Turabidin'den Berriye'ye. Aşiretler - Dinler - Diller - Kültürler (in Turkish). Pak Ajans Yayincilik Turizm Ve Diş Ticaret Limited şirketi. pp. 326–327, 341. ISBN 9789944360944.

- ^ "Will Kurds find a ray of hope in 2020?". Al-Monitor. 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- ^ "Qamishli Kurds commemorate 2004 uprising". Syria Direct. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Keser-Kayaalp, Elif (2018), Nicholson, Oliver (ed.), "Nisibis", The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, retrieved 2020-11-28

- ^ Mechanisms of Communication in the Assyrian Empire. "People, gods, & places." History Department, University College London, 2009. Accessed 18 Dec 2010.

- ^ Lendering, Jona. "Nisibis Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine." Accessed 18 Dec 2010.

- ^ Lendering, Jona. Assyrian Eponym List Archived 2016-12-27 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 18 Dec 2010.

- ^ Talmud, Sanhedrin 32b

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Mithridates the Great, Rome's Indomitable Enemy, p. 139; Lee Fratantuono, Lucullus, the Life and Campaigns of a Roman Conqueror, pp. 104–105; Dio Cassius, XXXVI, 6–7; Eutropius, Breviarium, 6.9.1.

- ^ Dio Cassius, LXVIII, 23

- ^ Dio Cassius, LXXV, 23

- ^ Cowan, Ross (2009). "The Battle of Nisibis, AD 217". Ancient Warfare. 3 (5): 29–35. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Harrel, John S. The Nisibis War, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Harrel, John S. The Nisibis War, p. 82; Dodgeon and Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Harrel, John S. The Nisibis War, pp 82–83; Dodgeon and Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars, pp. 193–206.

- ^ "SOZOMENOS, ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY, § 5.3".

- ^ Iranica: IRAQ i. IN THE LATE SASANID AND EARLY ISLAMIC ERAS

- ^ Jonsson, David J. (2005). The Clash of Ideologies. Xulon Press. p. 181. ISBN 1-59781-039-8.

- ^ Lieu, Samuel. "Nisibis" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ^ a b Tuncel, Metin (2007). "Nusaybin". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 33 (Nesi̇h – Osmanlilar) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 269–270. ISBN 978-975-389-455-5.

- ^ Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: a Complete History. London: Tauris. p. 378.

- ^ Kieser, Hans Lukas; Plozzo, Elmar, eds. (2006). Der Völkermord an den Armeniern, die Türkei und Europa. Chronos Verlag. p. 82. ISBN 978-3-0340-0789-4.

- ^ Üngör, Uğur (2005). A Reign of Terror (PDF). University of Amsterdam. p. 75.

- ^ Rhétoré, Jacques (2005). Les chrétiens aux bêtes: souvenirs de la guerre sainte proclamée par les Turcs contre les chrétiens en 1915. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf. p. 129. ISBN 2204072435.

- ^ "The Extermination of Ottoman Armenians by the Young Turk Regime (1915-1916) | Sciences Po Mass Violence and Resistance - Research Network". extermination-ottoman-armenians-young-turk-regime-1915-1916.html. 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2020-06-16.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Altuğ, Seda and Benjamin Thomas White (Jul–Sep 2009). "Frontières et pouvoir d'État: La frontière turco-syrienne dans les années 1920 et 1930". Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire. doi:10.3917/ving.103.0091.

- ^ Gibert, André; Févret, Maurice (1953). "La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique". Géocarrefour. 28 (1): 11. doi:10.3406/geoca.1953.1294 – via Persee.

- ^ Simon, Reeva, Michael M. Laskier, and Sara Reguer (2003). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 328. ISBN 9780231107976.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oruc, Berguzar (2006-10-19). "Ermeni köyu'nde toplu mezar". Dicle Haber (in Turkish). Özgür Gündem. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Gunaysu, Ayse (2006-11-07). "Toplu mezar Ermeni ve Süryanilere ait". Özgür Gündem (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Belli, Onur Burcak (2007-04-27). "Truth of mass grave eludes Swedish professor". Turkish Daily News. Archived from the original on 2010-07-31. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ "Blogian (www.blogian.net) » Genocide Mass Grave Manipulated in Turkey". Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ "Toplu mezarla yüzleşme vakti". Özgür Gündem (in Turkish). 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Oruc, Berguzar (2006-10-22). "Toplu mezar gizleniyor". Dicle Haber. Özgür Gündem. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Gusten, Susanne (2012-03-21). "Sensing a Siege, Kurds Hit Back in Turkey". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ^ "Solidarity with Nusaybin Mayor Ayse Gokkan". www.jadaliyya.com. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ^ 2 HDP deputies go on hunger strike to end days-long Nusaybin curfew Archived 2015-11-20 at the Wayback Machine dated November 19, 2015, at todayszaman.com, accessed 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Kurds capture 50% of Turkish city on the border with Syria". Al-Masdar News. 2016-03-23. Archived from the original on 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- ^ "Nusaybin, the Turkish city where war is now a way of life". The Independent. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Images reveal devastating impact of Turkish military's offensive in Turkey's predominantly Kurdish city of Nusaybin - Nordic Monitor". nordicmonitor.com. 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Nusaybin'den son görüntüler" (in Turkish). NTV. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Vali devre dışı, Nusaybin'i asker yönetecek: 30 bin sivil..." Cumhuriyet. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Nusaybin'de PKK'ya ağır darbe!". Milliyet. 4 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Nusaybin'de sokağa çıkma yasağı kaldırıldı". Cumhuriyet. 25 July 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "Managing Turkey's PKK Conflict: The Case of Nusaybin". Crisis Group. May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Turkey, Syria and the Kurds: South by south-east". The Economist. 20 October 2012.

- ^ Mahalle, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Erkınay Tamtamış, H.K. (2022). "Nusaybin Mahalle Adlarına Anlambilimsel Bir Bakış". Mukaddime (in Turkish). 13 (1): 180.

- ^ "June Climate History for Nusaybin | Local | Turkey".

- ^ Zalewski, Piotr (5 April 2012). "How Bashar Assad Has Come Between the Kurds of Turkey and Syria". Time. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Yıldırım, Ayşe (2013), Devlet, Sınır, Aşiret: Nusaybin Örneği (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in Turkish), Hacettepe University, retrieved 6 May 2016

- ^ Halifeoğlu, Fatma Meral (2006). "SAVUR GELENEKSEL KENT DOKUSU İLE SOSYAL YAPI İLİŞKİSİ ÜZERİNE BİR İNCELEME". Elektronik Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 5 (17): 76–84. ISSN 1304-0278. Archived from the original on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ^ Sykes, Mark (1904). Dar-ul-Islam: A Record of a Journey Through Ten of the Asiatic Provinces of Turkey. Bickers & Son. p. 264.

- ^ Tan, Altan (2018). Turabidin'den Berriye'ye. Aşiretler - Dinler - Diller - Kültürler (in Turkish). Pak Ajans Yayincilik Turizm Ve Diş Ticaret Limited şirketi. p. 326. ISBN 9789944360944.

- ^ a b https://www.sosyalarastirmalar.com/articles/mardin-population-census-republic-of-turkey-by-first-results.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Son Süryaniler de göç yolunda". Evrensel. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Nusaybin'in son Süryani ailesi: Terk etmeyeceğiz". Evrensel. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 941]

- ^ "Resignations and Appointments, 25.10.2024" (Press release). Holy See Press Office. 25 October 2024. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

Sources and external links

edit- Lieu, Samuel (2006). "NISIBIS". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Nisibis, Catholic Encyclopedia

- GCatholic, Armenian Catholic titular see

- GCatholic, Chaldean Catholic titular see

- GCatholic, Latin Catholic titular see

- GCatholic, Maronite titular see

- Turkish News - Latest News from Turkey, Hürriyet Daily News and Economic Review

- The Battle of Nisibis, AD 217