There are nine national parks located in the state of California managed by the National Park Service. National parks protect significant scenic areas and nature reserves, provide educational programs, community service opportunities, and are an important part of conservation efforts in the United States. There are several other locations inside of California managed by the National Park Service, but carry other designations such as National Monuments. Many of the national parks in California are also part of national forests and National Wildlife Refuges, and contain Native American Heritage Sites and National Monuments.

Parks

editChannel Islands

editThe Channel Islands National Park was established on March 5, 1980 and is located on five of the eight Channel Islands off the coast of California; all of the islands are located in Santa Barbara County except Anacapa Island which is located in Ventura County. The park covers a total area of almost 250,000 acres (1,000 km2).[1][2][3] The National Park Service works with various organizations to host educational, conservation, and scientific programs at the park.[4] The five islands which comprise the park are:[a][5]

- Santa Cruz Island (Spanish: Isla Santa Cruz, Chumash: Limuw) is the largest island in California and largest of the eight islands in the Channel Islands archipelago. It forms part of the northern group of the Channel Islands.[6] Santa Cruz is 22 miles (35 km) long and 2 to 6 miles (3 to 10 km) wide with an area of over 61,000 acres (250 km2).[7][8][9]

- San Miguel Island (Island Chumash: Tuqan) is the farthest west of the Channel Islands; it is the sixth-largest of the eight Channel Islands covering over 9,000 acres (3,600 ha), including offshore islands and rocks. Prince Island, 700 m (2,300 ft) off the northeastern coast, measures 35 acres (14 ha) in area. The island, at its farthest extent, is 8 miles (13 km) long and 3.7 miles (6.0 km) wide.[10][11]

- Santa Rosa Island (Chumash: Wi'ma) is the second largest of the Channel Islands covering over 53,000 acres (210 km2). Santa Rosa island is located about 26 miles (42 km) off the coast of Santa Barbara, California. The terrain consists of rolling hills, canyons, and a coastal lagoon. The island's highest point is Vail Peak, at 1,589 feet (484 m).[12][13]

- Anacapa Island is the smallest of the island chain and also the closest of the Channel Islands to the mainland. It is 9 miles (14 km) across the Santa Barbara Channel to the nearest point on the mainland and lies southwest of the city of Ventura, California.[14] It is the only one of the Channel Islands to have a non-Spanish-derived name; Anacapa comes from the Chumash word "Anyapax", meaning "illusion".[15] Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed by the island in 1542; George Vancouver labeled the island "Enecapa" on a 1790 chart; the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey labeled the island "Anacapa" in 1854.[16] Anacapa Island is home to the Anacapa Island Lighthouse a national historic site.[17][18]

- Santa Barbara Island is located about 38 miles (61 km) from the Palos Verdes Peninsula. With a total area of about 640 acres (2.6 km2), it is the smallest of the eight Channel Islands and is the southernmost island in the chain. The highest point on the island is Signal Hill, at 634 ft (193 m). The island was named by Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno, who sighted the island on 4 December 1602, the feast day dedicated to Saint Barbara.[19]

The islands are home to an array of significant natural resources and cultural sites; all of the islands contain national archeological districts except Santa Rosa Island. In 1976 all eight of the islands became a biosphere reserve as part of the Man and the Biosphere Programme under UNESCO.[20][2]

The Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary is a protected area established May 5, 1980 encompassing the waters from mean high tide to 6 nautical miles (11 km) around Channel Islands National Park, covering an area of approximately 1,470 square miles (3,800 km2). The National Marine Sanctuary program is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and conducts educational programs, oversees conservation efforts, scientific research, and national resource stewardship. The sanctuary protects a wide range of marine species and more than 150 historic shipwrecks.[21][22]

The islands are a place of cultural significance for the Chumash people.[23][24][25][26]

Death Valley

editDeath Valley National Park straddles the California–Nevada border, east of the Sierra Nevada range. The park contains Death Valley, the northern section of Panamint Valley, the southern section of Eureka Valley, and most of Saline Valley.[27] The Death Valley National Monument was declared in 1933; the park was substantially expanded and became a national park in 1994.[28] The park protects over 3,000,000 acres (12,000 km2).[29]

Death Valley is the largest national park in the contiguous United States, and the hottest, driest and lowest of all the national parks in the United States. The second-lowest point in the Western Hemisphere is in Badwater Basin, which is 282 feet (86 m) below sea level. More than 93% of the park is a designated U.S. Wilderness Area.[30][31][32] UNESCO included Death Valley as the principal feature of its Mojave and Colorado Deserts Biosphere Reserve in 1984.[33]

Despite its name, Death Valley National Park is home to a wide variety of plants and animals in its diverse ecosystem and microecosystems.[34] The Death Valley pupfish (Cyprinodon salinus), also known as Salt Creek pupfish, is a small species of fish found only in Death Valley National Park; the pupfish is endemic to two small, isolated locations and is currently classified as an endangered species.[35][36][37]

Notable locations inside the park are: Badwater Basin, Dante's View, Darwin Falls, Racetrack Playa, Rainbow Canyon, Telescope Peak, Titus Canyon, and Ubehebe Crater.

Joshua Tree

editThe Joshua Tree National Park is in southeastern California, east of Los Angeles and San Bernardino, near Palm Springs, California. It takes its name from the Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) native to the Mojave Desert.[38][39][40]

Minerva Hoyt led a campaign to convince the state and federal governments to protect the area; it was declared a national monument in 1936;[41] The monument was redesignated as a national park on October 31, 1994, by the Desert Protection Act.[42][38] [43] The park currently covers an area of over 790,000 acres (1,234.4 sq mi; 3,197.0 km2) – slightly larger than the state of Rhode Island; 429,690 acres (671.4 sq mi; 1,738.9 km2) of the park is a National Wilderness Preserve.[44][45] Straddling San Bernardino and Riverside Counties, the park includes parts of both the higher Mojave Desert and the lower Colorado Desert, each containing an ecosystem determined primarily by elevation. The Little San Bernardino Mountains run across the southwest edge of the park.[46]

Notable Joshua Tree scenic areas and trails in the park include: Fortynine Palms Oasis, Hidden Valley (Joshua Tree National Park), Lost Horse Mine, Lost Palms Oasis Trail (Joshua Tree National Park), and Ryan Mountain.

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks

editThe Kings Canyon National Park and Sequoia National Park adjoin each other and are administered together by the National Park Service as Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.[47]

Kings Canyon

editKings Canyon National Park is located in the southern Sierra Nevadas, in Fresno and Tulare counties. Currently the park covers 461,901-acre (186,925 ha).[b][49]

Originally established in 1890 as General Grant National Park, created to protect a small area of giant sequoias from logging, the park was greatly expanded and renamed to Kings Canyon National Park on March 4, 1940. The park is also a national wilderness area. Kings Canyon is north of and contiguous with Sequoia National Park, and both parks are jointly administered by the National Park Service as the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.[47][50][51][52]

The park consists of two main areas: General Grant Grove, home of the General Grant tree and Cedar Grove. The park's namesake, Kings Canyon, is a rugged glacier-carved valley more than a mile (1,600 m) deep. Other natural features include multiple 14,000-foot (4,300 m) peaks, high mountain meadows, swift-flowing rivers, and some of the world's largest stands of giant sequoia trees. The canyon is drained by the Middle and South Forks of the Kings River. Kings Canyon is home to over 60 recreational trails; combined the Pacific Crest Trail[c] and the John Muir Trail[d] traverse the entire length of the park, from north to south.[53][54][55]

Sequoia

editSequoia National Park is in the southern Sierra Nevada, northeast of Bakersfield, California. Because the parks are adjacent to each other, Kings Canyon National Park and Sequoia National Park are administered together as the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks by the National Park Service;.[47] In 1976, UNESCO designated the park as the Sequoia-Kings Canyon Biosphere Reserve.

The park was established on September 25, 1890 to protect over 400,000 acres (1,600 km2) of mountainous forest wilderness and became a national park at the same time the National Park Service was founded on August 25, 1916;[56] today the park protects 629 square miles (1,630 km2). The park's giant sequoia forests are part of 202,430 acres (819.2 km2) of old-growth forests protected by Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. The park is home to the highest mountain in the contiguous United States, Mount Whitney (14,505 feet (4,421 m)). Approximately 85 percent of the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks is a wilderness area inaccessible by road. The majority of the national park was designated as part of the Sequoia-Kings Canyon Wilderness area in 1984 and the southwest portion of the park was protected as the John Krebs Wilderness in 2009.[b][57][58]

The park is known for the giant sequoia trees it is named after, including the General Sherman tree, by volume the largest tree on Earth. The General Sherman tree grows in an area of the park called the Giant Forest, which contains five of the ten largest trees in the world. The Giant Forest is connected by the Generals Highway to General Grant Grove in Kings Canyon National park, home of the General Grant tree which is one of the other largest giant sequoias in existence.[59]

Lassen Volcanic Park

editLassen Volcanic National Park is located in Lassen County in northeastern California and is known for its numerous volcanoes.[60] The namesake feature of the park is Lassen Peak, the largest plug dome volcano in the world and the southernmost volcano in the Cascade Range.[61] The park is one of the few areas in the world where all four types of volcano can be found: plug dome, shield, cinder cone, and stratovolcano. From May 1914 until 1917, a series of eruptions occurred on Lassen.[62][63][64]

Lassen Volcanic National Park began in 1907 as two separate national monuments: Cinder Cone National Monument and Lassen Peak National Monument.[65] Because of the recent volcanic activity and the area's scenery, Lassen Peak, Cinder Cone, and the area surrounding were established as a National Park on August 9, 1916.[66][67][68] The park currently protects over 166 square miles (430 km2).[64]

The source of heat for the volcanism in the Lassen area is subduction of the Gorda Plate diving below the North American Plate off the Northern California coast. The area surrounding Lassen Peak is still active with boiling mud pots, fumaroles, and hot springs.[69]

Pinnacles

editPinnacles National Park is a mountainous area located east of the Salinas Valley in Central California. The park is approximately 40 miles (64 km) inland from the Pacific Ocean and approximately 80 miles (130 km) south of the San Francisco Bay Area. The park is in the southern portion of the Gabilan Range, part of California's Coast Ranges. Pinnacles is the ninth location in California to become part of the National Park System. In 1975 the park occupied over 16,000 acres (65 km2), increasing to the present size of over 26,000 acres (110 km2) through expansions including the 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) Pinnacles Ranch and Bacon Ranch,[70] and the Clinton administration's Proclamation 7266 which increased the size of the park by 7,900 acres (32 km2) to protect more caves. The elevation in the park ranges from 824 to 3,304 feet (251 to 1,007 m) at the peak of North Chalone Peak.[71][72][73] The park is also home to Pinnacles National Monument, an area of spirelike rock formations in the Gabilan Range area.[74]

The park's is named for the eroded rocky spires which are the remnants of an ancient volcanic field. The majority of the park is also protected as a national wilderness. The park is divided by rock formations into eastern and western areas, connected by hiking trails. The rock formations provide for extensive views that attract rock climbing enthusiasts.[75] The park features talus caves which are home to at least thirteen different species of bats;[76] the park is an excellent habitat for prairie falcons, and is a protected release site for California condors hatched in captivity.[77][78]

Pinnacles was established under the Antiquities Act as a national monument in 1908 by President Theodore Roosevelt,[73] and was redesignated as a national park by Congressional legislation in 2012 that was signed into law by President Barack Obama on January 10, 2013.[79] The legislation designates the Pinnacles Wilderness as the Hain Wilderness in commemoration of Schuyler Hain's efforts to establish the national monument.[80][81][78]

Redwoods

editThe Redwood National and State Parks are a network of three state and one national park located along the coast of northern California within Del Norte and Humboldt Counties. The National Park Service and the California Department of Parks and Recreation administratively merged responsibility Redwood National Park with the three abutting Redwood State Parks in 1994 to streamline administration, forest management and resource stabilization.[82][83]

The park network includes:

- Redwoods National Park

- Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park[84]

- Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park[85]

- Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park[86]

Humboldt Redwoods State Park and Big Basin Redwoods State Park are California state Redwood parks which are part of the Northern California coastal forests, but are not a part of the Redwood National and State Parks complex.[87]

In 1850, old-growth redwood forest covered more than 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of the California coast. Today the parks protect the remaining Redwood forest area, a combined 139,000 acres (560 km2) area of old-growth temperate rainforests. The four parks protect almost half of all remaining coastal redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) old-growth forests, totaling an area of over 38,000 acres (150 km2) with 37 miles (60 km) of natural coastline. Coastal redwoods are among the tallest, oldest, and most massive tree species on Earth.[88]

After decades of unrestricted logging, efforts toward conservation of the Redwood forest started. The work of the Save the Redwoods League, founded in 1918 to protect the remaining old-growth redwoods, resulted in the creation of the several state parks. Efforts by the Save the Redwoods League, the Sierra Club, and the National Geographic Society to create a national park began in the early 1960s and Redwood National Park was created in 1968. The parks are currently managed jointly by the California Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service.[89][90][91]

The Redwood National and State Parks are one of twenty–four World Heritage Sites in the United States; the committee overseeing the evaluation noted the existence of over fifty prehistoric archaeological sites and the research on the area by Humbolt State University.[92] The park is also a part of the California Coast Ranges International Biosphere Reserve.[93]

In addition to protecting the redwoods, the ecosystem of the parks protect a number of threatened species such as the tidewater goby, Chinook salmon, northern spotted owl, and Steller's sea lion,[94] while providing educational programs and recreation facilities and numerous hiking and walking trails throughout the park.[95][96]

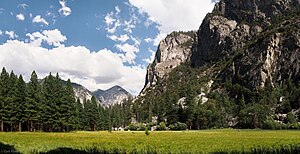

Yosemite

editYosemite National Park is located in central California in the western Sierra Nevada; the park borders the Sierra National Forest to the southeast and Stanislaus National Forest to the northwest and extends Tuolumne, Mono, Madera, and Mariposa counties. Three wilderness areas adjoin the park: the Ansel Adams Wilderness to the southeast, the Hoover Wilderness to the northeast, and the Emigrant Wilderness to the north. The park protects an area of almost 750,000 acres (3,000 km2); The elevation of the park ranges from 2,127 feet (648 m) to 13,114 feet (3,997 m).[97][98] The name "Yosemite" means "killer" in Miwok, and originally referred a tribe that was forced out of the area by the Mariposa Battalion. Previously, the area had been called "Ahwahnee" ("big mouth") by indigenous people. The indigenous tribe that lived in the Valley were called Yosemites by other tribes because they were formed of renegades from the Paiutes. The term "Yosemite" in Miwok is easily confusable with a similar term for "grizzly bear".[99][100]

Almost the entire park is designated as a wilderness area;[101] the park contains multiple ecosystems such as chaparral and oak woodland, lower montane forest, upper montane forest, subalpine zone, and alpine and protects a wide biological diversity of flora and fauna native to California and the Sierra Nevada. Yosemite is one of twenty–four World Heritage Sites in the United States.[102]

Yosemite was at the heart of the development of the national park system. Galen Clark worked together with other conservationists to protect Yosemite Valley from development; this ultimately lead President Abraham Lincoln to sign the Yosemite Grant Act in 1864. The movement to have Congress declare Yosemite a national park began soon after the grant and the valley and surrounding mountains and wilderness became a national park in 1890.[103]

Notable areas protected inside Yosemite include: Tunnel View, El Capitan, Sentinel Dome and Half Dome, Tuolumne Meadows, Dana Meadows, Clark Range, Cathedral Range, and Kuna Crest.

About the National Park Service

editThe National Park Service (NPS) is the agency of the United States Government that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other historical properties with various designations. The agency was created on August 25, 1916 through the National Park Service Organic Act. The National Park Service is a part of the Department of the Interior. The agency is charged with both preserving the ecological and historical integrity of the places entrusted to its management and also making them available and accessible for public use and enjoyment.[104][105][106]

See also

edit- California Desert Protection Act of 1994[e]

- List of national parks of the United States

- List of National Historic Landmarks in California

- National Register of Historic Places listings in California

- U.S. Wilderness Area

- National Wilderness Preservation System

- Marine protected area

- National park

- United States Forest Service

- National forest (United States)

- Bureau of Land Management

- Antiquities Act

- Theodore Roosevelt

- John Muir

References

editGeneral references

edit- Barbour, M. G., Lydon, S., Borchert, M., Popper, M., Whitworth, V., & Evarts, J. (2001). Coast Redwood: A Natural and Cultural History. Cachuma Press.

- Chiles, F. (2015). California's Channel Islands. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Cunningham, B., & Cunningham, P. (2006). Hiking California's Desert Parks: A Guide to the Greatest Hiking Adventures in Anza-Borrego, Joshua Tree, Mojave, and Death Valley. Globe Pequot.

- Dilsaver, L. M., & Tweed, W. C. (1990). Challenge of the Big Trees. National Park Service.

- Dilsaver, L. M. (2015). Joshua Tree National Park: A History of Preserving the Desert. National Park Service.

- Dunning, J., & Thron, D. (1998). From the Redwood Forest: Ancient Trees and the Bottom Line: A Headwaters Journey. Chelsea Green Pub Co.

- Eggers, M. (2004). Mining History and Geology of Joshua Tree National Park. San Diego Association of Geologists.

- Harris, A. G., Tuttle, E., & Tuttle, S. D. (1997). Geology of National Parks (5th revised edition). Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

- Harris, D. (1995). The Last Stand: The War Between Wall Street and Main Street over California’s Ancient Redwoods. Crown Publishing.

- Hewes, J. J. (1995). Redwoods: The World’s Largest Trees. Smithmark Pub.

- Johnstone, P., & Palmquist, P. E. (Eds.). (2001). Giants in the Earth: The California Redwoods. Heyday Books.

- Kaiser, J. (2010). Joshua Tree: The Complete Guide (4th edition). Destination Press.

- Kiver, E. P., Harris, D. V. (1999). Geology of U.S. Parklands (5th edition). John Wiley & Sons.

- League, S. the R., & Hodder, S. (2019). The Once and Future Forest: California’s Iconic Redwoods. Heyday Books.

- Maloof, J. (2016). Nature’s Temples: The Complex World of Old-Growth Forests. Timber Press.

- Mihaly, C. (2018). California's Redwood Forest. Focus Readers.

- Morley, J. M. (1992). Muir Woods: The Ancient Redwood Forest Near San Francisco. Smith/Morley.

- Noss, R. F. (Ed.). (1999). The Redwood Forest: History, Ecology, and Conservation of the Coast Redwoods. Island Press.

- Rothman, H. K., & Miller, C. (2013). Death Valley National Park: A History. University of Nevada Press.

- Schaffer, J. P. (1999). Yosemite National Park: A Natural History Guide to Yosemite and Its Trails. Berkeley: Wilderness Press.

- Schoenherr, A. A., Feldmeth, C. R., & Emerson, M. J. (1999). Natural History of the Islands of California. University of California Press.

- Sharp, R. P., & Glazner, A. F. (1997). Geology Underfoot in Death Valley and Owens Valley. Mountain Press Publishing Company.

- Vieira, L. (1994). The Ever-Living Tree: The Life and Times of a Coast Redwood. Walker & Co.

- Wallace, W. J. (1978). Ancient peoples and cultures of Death Valley National Monument (1st edition). Acoma Books.

- Wuerthner, G. (1994). Yosemite: A Visitor's Companion. Stackpole Books.

- Zarki, J. W. (2015). Images of America: Joshua Tree National Park. Arcadia Publishing.

Notes

edit- ^ Anacapa Island and Santa Barbara Island are national monuments, both established before the park in 1938.

- ^ a b The Sequoia-Kings Canyon Wilderness encompasses over 468,000 acres (189,000 ha) in Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks.[48]

- ^ The Pacific Crest trail passes through 25 national forests and 7 national parks.

- ^ The John Muir trail passes through Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks.

- ^ The California Desert Protection Act of 1994 (16 U.S.C. §§ 410aaa through 410aaa-83, October 31, 1994): The Act establishes the Death Valley and Joshua Tree National Parks and the Mojave National Preserve.

Citations

edit- ^ "Channel Islands National Park". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Treasured Islands: Channel Islands National Park". National Park Foundation. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Science Explorer: Channel Islands National Park". United States Geological Survey. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Cheri Carlson (September 2, 2016). "Bringing Channel Islands National Park to the people". Ventura County Star. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Channel Islands National Park". California Beaches. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Santa Cruz Island". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Santa Cruz Island - Island Packers Cruises". islandpackers.com. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ "Chumash Place Names". Archived from the original on April 1, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ "Santa Cruz Island in California". nature.org. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Chumash Place Names". Archived from the original on April 1, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ "San Miguel Island". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Chumash Place Names".

- ^ "Santa Rosa Island". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Anacapa Island Restoration Project" (PDF). Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Harrington, John P. John P. Harrington's Notes, Reel 68.

- ^ Chiles, Frederic (2015). California's Channel Islands. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780806146874.

- ^ "Anacapa Island: Coast Guard Lighthouses". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Anacapa Island". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Santa Barbara Island". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Channel Islands Biosphere Reserve: Ecological Sciences for Sustainable Development". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary". Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Rick, Torben C.; Erlandson, Jon M.; Vellanoweth, René L.; Braje, Todd J. (2005). "From Pleistocene Mariners to Complex Hunter-Gatherers: The Archaeology of the California Channel Islands". Journal of World Prehistory. 19 (3): 169–228. doi:10.1007/s10963-006-9004-x. S2CID 162492009.

- ^ Kennett, Douglas J. (2005). The Island Chumash: Behavioral Ecology of a Maritime Society (1 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24302-6. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppdj7. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Arnold, Jeanne E. (2007). "Credit Where Credit Is Due: The History of the Chumash Oceangoing Plank Canoe". American Antiquity. 72 (2): 196–209. doi:10.2307/40035811. JSTOR 40035811. S2CID 145274737. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Perry, Jennifer E. (2007). "Chumash Ritual and Sacred Geography on Santa Cruz Island, California". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 27 (2): 103–124. JSTOR 27825862. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Casey, Mary F. (2017). "Ten Thousand Needles: Material Culture, Native Power, and Adaptation along the Santa Barbara Channel, 1769–1824". Southern California Quarterly. 99 (2): 119–139. doi:10.1525/scq.2017.99.2.119. JSTOR 26413441. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "Death Valley National Park". Britannica. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ National Park Index (2001–2003), p. 26

- ^ "12 Things You Didn't Know About Death Valley". U.S. Department of the Interior. October 15, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ "Death Valley National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Death Valley". National Parks Conservation Association. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Rothman, H. K.; Miller, C. (2013). Death Valley National Park: A History. University of Nevada Press.

- ^ "Mojave and Colorado Deserts Biosphere Reserve". California. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Trevor B. Persons and Erika M. Nowak (2006). "Inventory of amphibians and reptiles at Death Valley National Park". United States Geological Survey. Open-File Report. doi:10.3133/ofr20061233. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Cyprinodon salinus". FishBase. December 2015 version.

- ^ "Salt Creek pupfish". U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "Death Valley National Park". National Geographic. November 3, 2015. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "Joshua Tree National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "Joshua trees may disappear with climate change—but scientists are working to save them". National Geographic. October 15, 2018. Archived from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Joshua Tree National Park". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Netburn, Deborah (February 14, 2019). "How a South Pasadena matron used her wits and wealth to create Joshua Tree National Park". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ . August 10, 1936 – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Park History". Joshua Tree National Park, NPS. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ Land Resources Division (December 31, 2016). "National Park Service Listing of Acreage (summary)" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ "Wilderness area of Joshua Tree National Park". National Park Service. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "A Desert Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Sequoia-Kings Canyon Wilderness". Wilderness Connect. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Kings Canyon National Park". Britannica. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks, California". Recreation.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Challenge of the Big Trees (Chapter 4)". National Park Service. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Editors of Encyclopaedia, ed. (2019). "Kings Canyon National Park". Encyclopedia Britannica.

{{cite web}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ "Best trails in Kings Canyon National Park". AllTrails.com. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Kohn, B., Benson, S. (2016). Lonely Planet Yosemite, Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks. Lonely Planet Publications.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ White, Mike (2012). Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks: Your Complete Hiking Guide. Wilderness Press.

- ^ Dilsaver, L. M.; Tweed, W. C. (1990). "Chapter 4: Parks and Forests: Protection Begins (1885-1916)". Challenge of the Big Trees. National Park Service.

- ^ Dilsaver, L. M.; Tweed, W. C. (1990). "Chapter 5: Selling Sequoia: The Early Park Service Years (1916-1931)". Challenge of the Big Trees. National Park Service.

- ^ "Wilderness - Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Nature - Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park". Los Angeles Times. August 9, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "HOTSPOT: California On The Edge: Cascade Range Volcanoes". California Academy of Sciencies. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic Center". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "Lassen Volcanic National Park". Britannica. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "A Guide to California's Lassen Volcanic National Park". National Geographic. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ "The Story of the Antiquities Act". National Park Service.

- ^ "Lassen Volcanic National Park". National Park Foundation. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "California's Lassen Volcanic National Park". National Geographic. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Clynne, Michael A; Janik, Cathy J; Muffler, LJP. "Hot Water in Lassen Volcanic National Park: Fumaroles, Steaming Ground, and Boiling Mudpots" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ "Spanish Missionaries and Early Settlers - Pinnacles National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Pinnacles National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Pinnacles becomes a national park — the closest to Bay Area". The Mercury News. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Oberg, Reta R. (1979). "Administrative History of Pinnacles National Monument" (Document). National Park Service.

- ^ "Pinnacles National Monument". Britannica. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Climbing - Pinnacles National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "Status of the Caves - Pinnacles National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "California Condors at Pinnacles - Pinnacles National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Timothy Babalis (2009). "The Heart of the Gabilans: An Administrative History of Pinnacles National Monument" (PDF). National Park Service.

- ^ Richard Simon (December 31, 2012). "Pinnacles National Monument set to become a park". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ "History & Culture - Pinnacles National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ An Act to designate certain lands within units of the national park system as wilderness; to revise the boundaries of certain of those units, and for other purposes. Pub. L. 94–567, H.R. 13160, 90 Stat. 2692, enacted October 20, 1976

- ^ "Learn About the Park - Redwood National and State Parks". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Basic Information - Redwood National and State Parks". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park". California State Parks. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park". California State Parks. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Prairie Creek Redwoods SP". California State Parks. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Redwood National Park". Britannica. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Everything to know about Redwood National and State Parks". National Geographic. Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Redwood National and State Parks". Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Willard E. Pratt. "Chronology: Establishment of the Redwood National Park" (PDF). Forest History Society.

- ^ Harris, D. (1995). The Last Stand: The War Between Wall Street and Main Street over California's Ancient Redwoods. Crown Publishing.

- ^ "The Redwoods Project". Humbolt State University. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Redwood National and State Parks". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Threatened and Endangered Species - Redwood National and State Parks". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Best trails in Redwood National Park". All Trails. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Barbour, Michael G.; Lydon, Sandy; Borchert, Mark; Popper, Marjorie; Whitworth, Valerie; Evarts, John (2001). Coast Redwood: A Natural and Cultural History. Cachuma Press. ISBN 978-0-9628505-5-4.

- ^ "Yosemite National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Everything to know about California's Yosemite National Park". National Geographic. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Beeler, Madison Scott (1955). "Yosemite and Tamalpais". Journal of the American Name Society. 3 (3): 185–186.

- ^ Wuerthner, G (1994). Yosemite: A Visitor's Companion. Stackpole Books.

- ^ "Park Statistics - Yosemite National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Yosemite National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Yosemite National Park Established". History.com. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "What We Do (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "What's In a Name? Discover National Park System Designations". National Park Service. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ^ "The National Park Service Organic Act (1916)". National Park Service.

Other sources

edit- This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

- This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

External links

editGeneral

- National Parks in California; Visit California.

- Map and list of national parks, monuments, and historic sites in California, National Park Service

- Map of Northern California; University of Texas

- Map of Southern California; University of Texas

Parks

- 1920s photographs of Death Valley and surrounding area; Digital History Collections, Utah State University.

- Historic Photos of Yosemite National Park, Brigham Young University.